|

The Firth of Clyde presents some peculiar features

which are of much interest. The long narrow lochs which stretch like

arms for many miles inland, carry the sea-water to the foot of the

Highland hills of Argyleshire, and, in the combination of mountain

slopes and salt-water with the tidal ebb and flow, are, in a

miniature form, a reproduction of the fiords so common on the

Norwegian coast. In many cases the latter still terminate in the

great ice-field or glacier, with snow-clad mountain summits. The

Clyde hills, however, unless in winter, are free from snow or ice.

By the student of geology many traces can still be seen around these

inlets that point to a time in the far-back history of our river,

when the glacier slowly crept down the valleys, the ice sheet being

floated away down to the opener waters beyond, carrying with it some

of the debris from the mountain slopes. Speaking of tho glacier

period, Mr. Bell, in his Rocks around Glasgow, says:

“So issuing In great volume from the mountain ranges

by the channels of these Highland lochs, Loch Fyne,

Lochs Ridden and Striven, Loch Eck and Holy Loch,

Loch Goil, Loch Long, the Gareloch, and Loch Lomond— all of which

are simply old glacier beds—the ice spread across what is now the

Firth of Clyde; part, as we have seen, taking an easterly and

south-easterly direction, and part, also, as shown by the markings

on either shore, proceeding down what is now the channel, past Bute

and the Cumbraes. There must, therefore, have been a ‘ shedding ’ or

parting of the ice near Gourock, and this may be one reason why the

boulders there are so abundant. At Kilmun point, where the Loch Eck

and the Loch Long glaciers coalesced, there would be formed a

‘medial moraine,’ which would be borne by the ice across the present

channel, and strewn where it impinged on the slopes of the opposite

hills.”

The deposits left by these movements are partly of a

clayey nature, and a classic interest surrounds certain beds which

are found on the banks of the river and firth; and it is to the late

Mr. Smith of Jordanhill that we owe the discovery of shells of an

Arctic type which had lain embedded since the glacial period,

contemporary living specimens being only now found in Arctic

regions. These shells can still be found in the beds of clay at

various points, one of which is at the mouth of the Balni-kailly

Burn, Bute, which enters the Kyles nearly opposite Colintraive pier.

Whether as a student of geology, natural history, or,

shall we call it, climatology, an observer will find much of

interest in the configuration of the lower part of the Clyde, from

where Loch Long terminates at Arrochar to the Craig of Ailsa itself,

which may be considered as the terminal mark of the firth. If anyone

will take a chart of the firth and note the soundings he will

observe a varied assortment of figures, with here and there a

characteristic letter attached. The figures represent in fathoms the

depths below low water, and the letters indicate the character of

the bottom. If we now compare these varied depths we may notice

that, although the depth increases in a general manner as we recede

from the shore, yet, at the lowest part of the firth, and where we

would naturally look for the deepest water, we have very much

shallower water than at many points higher up the firth. Thus, if we

take a line across from Girvan by Ailsa Craig to Campbeltown or the

Mull of Cantyre, we find that the soundings there vary very little,

preserving a fairly uniform value of 25 or 26 fathoms (immediately

outside it is 50 fathoms), while some miles higher up, off Arran,

they increase to about 70 fathoms, attaining at the north end of

that island to 90 fathoms, which again is exceeded in Loch Fyne, at

a point a few miles below Tarbert, by the great depth of 104

fathoms, or 621 feet. And thus one of the two great chimney-stalks

in Glasgow, which measures about 450 feet, would, if placed in the

water out at Ailsa Craig, have from about one-half to three-fourths

of its height above water, but would be completely submerged if

placed off' the north end of Arran; and in Loch Fyne, at the point

of greatest depth mentioned, it would be covered by about 170 feet

of water. Such a configuration points to a deep basin of water lying

more or less up the firth from its termination; hence if a

sufficiently great ebb-tide were to lay bare the plateau around

Ailsa Craig, there would be left inside an inland lake which, at its

deepest part, would be about 470 feet deep. Indeed, if we consider

that the level of the water has undoubtedly stood at one time much

higher than it is at present, Loch Lomond Will afford us an

illustration of such a changed condition of things, as it is obvious

that at one time what we now see as a fresh-water lake must have

been an arm of the sea not unlike Loch Long, and, indeed, might now

be united to it, as the narrow neck of land which divides these two

large sheets of fresh and salt water is not greatly raised above

sea-level. The deepest part of this inland and fresh-water loch is

over 100 fathoms, its lower part being separated by 6 or 7 miles of

low-lying ground from the river Clyde.

Besides this general depression in the firth there

are also subsidiary depressions at different points in the arms or

lochs already referred to; thus, the inner part- of the firth, or

that lying above the Cumbrae Islands, shows this same basin-like

structure, as we find deeper water about Dunoon than at Toward

Point; a little off Dunoon we find 56 fathoms, but off Toward Point

23 fathoms.

From the north end of Greater Cumbrae an elevation

all within the 20-fathom line runs northwards till it reaches its

highest part at Skelmorlie Buoy, on the bank of the same name, where

the depth is only 2f fathoms, it then slopes down rapidly to 44

fathoms off Wemyss point. A deep channel exists on the Skelmorlie

shore, which, along the measured mile course, varies from 38 to 45

fathoms.

Starting with the Gareloch, the highest up of the sea

lochs, and just at the commencement of the firth, we find '

that the entrance, which is narrow, has only a depth

of a few fathoms, 1 to 5, whilst about half-way up the depth reaches

23 fathoms. At the entrance to Loch Long the greatest depth is from

32 to 33 fathoms, whilst 44, 46, 48, and 50 are registered up

towards the mouth of Loch Goil. Considerably deeper water is also

found in this short loch or arm of Loch Long than at its entrance.

The Holy Loch is short and shallow, a depth of 14 fathoms being

pretty uniformly preserved throughout its centre.

The next important arm of the firth is Loch Striven,

which runs back among the Cowal hills for a distance of about 7

miles, and exhibits in the grand and lonely character of its scenery

much of that for which some of our far west Highland lochs are

justly celebrated. The deepest sounding at the mouth of this loch is

23 fathoms, deepening rapidly to 35 fathoms, and reaching to 40 and

41 fathoms about half-way up.

Coming to Loch Lyne, which stretches as a long narrow

valley far up into Argyleshire, we find that in the upper part, viz.

that running in a somewhat north-easterly direction from Otter, near

Ardrishaig, to beyond Inverary, we have at the narrow part of Otter

Ferry an irregular series of soundings varying from G to 23 fathoms,

whilst fully half-way up the depth reaches 82 fathoms. At the mouth

of the lower part of Loch Fyne we find the greatest depths marked to

be 79 and 84 fathoms, the greatest depth, as before stated, being

found higher up, and reaching to 104 fathoms, the depths above and

below this point being 96 fathoms. (See Chart of Firth, p. 16.)

Now, it is obvious that not only the peculiar

superficial configuration of this system of lea-water into which the

river Clyde flows, but the peculiar characteristics of the bottom

must affect the flow and ebb of the tide and the temperature of the

water. The tidal wave as it reaches our coasts is deflected around

the northern and southern ends of the island, and in like manner, to

a smaller extent, suffers considerable interruption to its course on

entering the Firth of Clyde by the Mull of Cantyre. Passing up from

the North Channel the island of Arran divides the stream, one part

reuniting again at the north end of that island and passing up Loch

Fyne and through the Kyles of Bute, the other part flowing past the

Cum-brae Islands and advancing up the upper lochs and the river

itself till reaching Glasgow.

The temperature of the deep water in the Firth of

Clyde and the neighbouring sea lochs has recently formed the subject

of careful experimental investigation, and the conclusion drawn from

the data obtained recorded in papers and reports. These interesting

researches were first begun in 1886, when the

steam-launch Medusa cruised about the firth and neighbouring lochs,

taking deep-water soundings and gathering much general and useful

information both as regards the waters and the creatures which live

in them. From these observations it was found that the distribution

of temperature depended largely on the depth and form of the sea

bottom. Surface temperature was lost at 10 fathoms down. The

temperature on the shallowest part off the Craig was higher than at

the bottom of the lochs. Speaking on this subject Dr. Mill says:

“ The work has so far brought out the following quite

new results. The temperature in the open channel south of the Mull

of Cantyre is always nearly uniform from surface to bottom; it

changes regularly with the advancing season and appears to he higher

all the year round than the mean of that of equally deep water

anywhere inside the Clyde Barrier Plateau. In the great Arran Basin

temperature is uniform from surface to bottom for a considerable

time when the warmth is at a minimum in early spring. As the weather

grows warmer the surface heats most rapidly! and the warmth slowly

spreads downwards, affecting the whole mass of water below the depth

of about 30 fathoms uniformly and slowly at first; but the distance

to which a rapid rise extends increases until past the autumnal

equinox. Then the surface commences to cool, the maximum occurs at

the middle, but is speedily transferred to the bottom, and gives the

early winter distribution of increase of temperature with depth.

Cooling ultimately takes place throughout until an exactly uniform

vertical distribution is established. The deep rock-basins resemble

the Arran Basin with its peculiarities relative to the open Channel

much exaggerated. They are comparatively isolated from tidal

influence, and exposed to the extremes of summer heat and winter

cold from tho proximity of steep mountainous walls down which much

surface water pours. The deep basins have a strong resemblance to

inland lakes in their great range of temperature at the surface and

small range at the bottom. The intermediate layers usually show

remarkable instances of the superposition of strata at different

temperatures. The phenomenon of a cold layer sandwiched between

warmer ones, and gradually sinking lower as summer advances, is

characteristic of all rock-basins tilled with sea-water, but was not

so marked this year as last in the Clyde lochs.”—Journal of the

Scottish Meteorological Society for 1886.

There appears to be about 31, per cent of salt in the

waters of the firth, and the deeper water is, in all cases, sal ter

than the surface water. In many cases calm patches of water are

noticeable on the surface when otherwise there are ripples due to

the wind, also oily-looking patches scattered about on calm days.

These patches may sometimes be noticed when becalmed while yachting,

and if closer attention be paid a distinct up-welling of the water

at these places can be detected. During the cruise of

the Medusa such patches were investigated, and it was found that in

one case, oft* the Mull of Cantyre, the temperature of the patch was

42° to 420,3, whilst that of the surrounding water was 43° to 45°'5;

the conclusion drawn by the observers was that such appearances were

due to the deeper and therefore colder water welling up from the

bottom.

The rise and fall of the tide around the coasts of

the firth is very varied on account of the configuration of the

channel; the action of the wind, too, has much to do with the range.

In looking over a chart of the firth we see that near the southern

end of Bute the range is 10 feet, at Ardrishaig from 6 to 9 feet, at

Inverary 10 feet, Loch Striven head 6 feet, Lochgoilhead 6 to 10

feet, at Arrochar 12 feet, and at Greenock 10 or 12 feet. At West

Loch Tarbert the tides arc so irregular that the familiar practice

of beaching lighters to tranship their cargoes, so common on the

shores of the firth, cannot be carried out, at least with the

certainty of a rise of tide at a stated time to get afloat again.

The range there is only from 1 to 4 feet. About Loch Crinan it

appears to vary from 3 feet at neap-tides to 8 feet at springs. At

the Mull of Cantyre the range is only 4 feet at springs. At the

Cumbrae Head the range of the tide at springs is about 12 feet. At

Toward Point the greatest range, which is in March, is about 14 feet

with a north wind. If the wind be southerly the ebb will be reduced

by as much as two feet. Around Ailsa Craig there appears to be

little or no range of tide. The speed of flow is, however, from 4 to

5 miles an hour.

The influence of the wind is very marked in such

narrow channels as occur about the firth. Southerly gales happening

at the time of springs, frequently cause Hooding of the lower parts

of our coast towns, whilst extreme ebbs occur with easterly winds,

causing difficulties sometimes in the launching of vessels on the

river, and in the taking of some of the coast piers by the river

steamers.

Where there is an island with a long narrow channel

at one end, we find that part of the tide coming up the firth keeps

to one side of the island and part to the other, like the island of

Bute, where it meets at a point in the Kyles about Southhall;

yachtsmen and fishermen, who are more or less dependent on the wind

and tide, can in this way gain advantage of the direction of flow of

both flood and ebb.

The times of high-water are also very varied. Thus,

at Ardrishaig, Kyles of Bute, Garroch Head and Loch Striven head,

the time of high-water is much the same, but at Skipness and West

Loch Tarbert it is about three hours later; at Inveraiy,

Lochgoilhead, and at Greenock, it is about a quarter of an hour

later.

The effect of wave action is often experienced on the

Firth of Clyde, the passage between Gourock and Dunoon and the

rounding of Toward Point having been long dreaded by passengers to

Rothesay, as also the rounding of the Farland Point going to

Millport, and the side sea experienced crossing at Wemyss Bay. The

winds which produce this disturbance are from the southward, having

a long fetch from the outside part of the firth, accompanied, it may

be, by a ground-swell from the deeper water outside. During the

ebb-tide, with a southerly wind, the effect is intensified, the

waves being higher and sharper. It is well known that the judging of

the height of waves is deceptive, and great variety exists in

individual minds as to the size of waves even with those accustomed

to see them. Thus, in the firth, within the Cumbraes, heights of

from 8 to 12 feet are quoted by steamboat captains and others

conversant with the firth in storms, whilst outside and beyond Arran

12 to 15 feet is assumed as an approximation. It is unlikely, in the

inner waters of the firth at least, that such extreme heights as 12

feet arc met with, from 6 to 10 feet being more probable. No doubt

where the water shoals the tendency of the wave is to rise and

break; thus in a southerly gale one experiences the sharpest heave

off the buoy on Toward Bank.

Where the waves are unaffected by special tidal

action, the rule devised by Mr. Thomas Stevenson, C.E., appears to

give fairly accurate results foil the height of waves in heavy

gales, Applying this formula to the waves coming up the channel, it

appears that for a height of G feet the fetch would require to be 1G

miles, and for a height of 8 feet 28½ miles.

It is generally recognized that there is extreme

difficulty in estimating approximately correct the heights of waves

at sea. A sensitive aneroid, however, readily indicates the rise and

fall of the ship, and might be employed for such investigation. As a

kind of gauge of the height of the waves in the inner parts of the

firth, it may be often noticed by passengers on rough nights who

cross from Wemyss Bay that the light on the floating gas buoy on

Skclmorlie Bank disappears regularly with every wave. Now, as the

height of the light is 14 feet above sea-level, this indicates a

considerable apparent height of wave. This buoy carries a bell for

fog-signalling, and being specially rounded off below to intensify

its swinging tendency in a swell, we cannot take the whole 14 feet

as representing the difference of level from trough to crest; but,

as the buoy is more or less inclined, something less would indicate

a real height of wave as already noted from direct observation.

The meteorological conditions of the Clyde valley are

somewhat varied, arising largely from the variations of altitude of

the different parts of the country through which the river takes its

course and the direction of the hill slopes which border it. In the

Upper Ward, which extends down to Carluke, a great part of the

country is moorland and rough pasture, but the soil in many places

is well suited for cultivation, the principal part of the arable

land lying near the Clyde. The soil becomes more clayey as the

boundary of the middle ward is approached, which, although showing

great variety, yet is principally clayey. Alluvial soil is met with

near the river and its tributaries, and a peaty earth is common in

some parts. In the lower ward the soil varies from clay to sand,

with alluvial bottoms along the Clyde.

The weather of the Upper Ward is steadier, and the

cold and heat more severe than lower down, and heavy rains

frequently fall in the higher parts. In the lower parts of

Lanarkshire the temperature is modified by the influence of the

Atlantic.

Looking over such reports as those published by the

Meteorological Society of Scotland we see the great variation of

temperature and rainfall in the different districts where records

are kept. Thus, if we take the report for the year ending December,

1SS5, we find that at Ar-drossan, on the eastern side of the firth,

the annual rainfall amounted to 30 inches. Crossing the country to

Paisley we find registered 33 inches; at Gasgow, 27 inches.

Following up the line of the Clyde valley we have at

Cambuslang, 26 inches; about Bothwell, 22; Hamilton, 29. Keeping by

the coast we find at Rothesay, 44 inches registered; at Greenock,

celebrated as a rainy place, we have the large quantity of 56

inches; at Helensburgh, on the opposite side of the river, 48

inches; and at Arrochar, at the head of Loch Long, the great

quantity of 71 inches fell in one year, or nearly 6 feet of water.

By the time we get up to Dumbarton we find that only 42 inches were

registered. Very nearly the same quantity of rain was registered on

opposite sides of the Clyde valley at points roughly north and south

of Glasgow; thus at Mugdock, near Milngavie, 8 miles from Glasgow,

where the service reservoir of the Loch Katrine water supply is

situated, the rainfall was about 42 inches, and at Ryat Linn,

another of the Glasgow reservoirs, but connected with the Gorbals

works on the south side of the river, a few miles from Glasgow, the

rainfall was about 41 inches; Glasgow, as already stated, coming in

between these two stations with 27 inches.

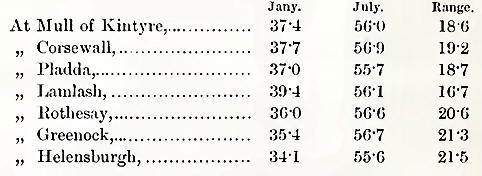

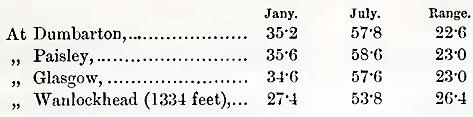

The variations of monthly mean temperatures in

degrees Fahrenheit throughout the year at various points in the

Clyde valley and firth are as follows:—

The island of Bute has long been celebrated for the

salubrity of its climate, and is well known as a health resort. The

climate is mild, as the following notes of temperature will show:

thus, the average temperature of Bute, taken over a period of nearly

fifty years’ observation, is given as 47°'34, the highest of any

year during that time being in 1828, when the average for that year

was 5CT73, the lowest average being 43o-40 in 1838. The highest

average temperature for July during that time was G3°'09 in 1852,

and the lowest average temperature for December was 31°’81 in 1874.

The highest temperature recorded during the same period was S53and

the lowest 14°. The rainfall is much less than at some points on the

mainland adjoining, the average fall taken over a large number of

years giving 48‘32 inches.

Freedom from sudden changes of temperature is

undoubtedly favourable to longevity, rapid variations affecting the

death-rate in a marked manner. The following extract refers to the

salubrity of some of our western islands:1 “The islands of Bute,

Arran, and Mull are peculiarly adapted as sanatoria for

consumptives, and their climates are highly conducive to restoring

energy in cases of lowered vitality and nervous exhaustion. After a

most careful study of Rothesay and its surroundings, climatically,

geographically, and socially, I am not surprised at its being

designated ‘ the Madeira of Scotland.’

"I must not neglect to mention the pleasant village

of Port-Bannatyne, situated at the head of the beautiful bay of

Karnes, about two miles from Bothesay, rendered charmingly

picturesque by its brilliant scenery, including the far-famed Kyles

of Bute. During the summer months the air at this health-inspiring

spot is purer than Bothesay, and certainly more buoyant and

invigorating.”

Prom a voluminous report on the weather of 1886 by

Professor Grant of the Glasgow Observatory, published in the Glasgow

Herald, it appears that the average annuel temperature at Glasgow

for the last ten years was 460-4. During 1886 the maximum

temperature in the shade was 76°'7 in July; the minimum, also in the

shade, being 15 '6 in February. The maximum in sun was B31°T in J

uly. The highest reading of the barometer was 30'681 in November;

the lowest reading being 27647 in December; the monthly range of the

latter month being 2-848 inches, and the average range for the year

being 1453 inches.

The rainfall was 32-179 inches, the greatest fall

being in September, when as much as 4-958 inches fell during a

period of 16 days. The least fall was in April, the depth during

that month being P160 inches, distributed over a period of 12 days.

The prevailing winds were from the south-west and

north-east, the former blowing during 84'29 days and the latter

79'43 days. The least frequent were the south-east winds, showing 14

5 days, and the north-west, 17'46 days. There were 64-92 days of

west wind, and 87‘29 of east wind; 48-21 days of south wind, and 23

90 of north wind

An interesting tabular statement gives the movements

of the air, from which it appears that the average hourly movement

for a period of 10 years was 1T6 miles per hour, the highest being

in 1877 with 13'2 miles per hour, and the lowest in 1879 with 109

miles. The mean temperature during 1886 was highest with the south

wind, which gave 49°'45, and lowest with the cast wind, which showed

only 43°-67. The south-west wind was the wettest, giving 8'57 inches

of rain in the year, and the north-west wind the driest with 0‘74

inches, and the north wind with T21 inches. The percentage of

possible sunshine for the year 1886 was 22'4.

Glasgow and the Clyde valley are occasionally visited

by strong gales, a pressure of as much as 55 lbs. per square foot

having been recorded at Glasgow Observatory. During a severe storm

in January, 18G8, 42 lbs. was registered. During the memorable Tay

Bridge storm a pressure of 37 lbs. was recorded, but the fury of the

storm so damaged the instrument that a complete record could not be

obtained. After tin; inquiry as to the cause of the Tay Bridge

accident the Board of Trade determined to adopt 56 lbs. per square

foot of surface as the wind pressure to be allowed for in designing

structures such as bridges. In 1881 a severe storm registered a

pressure of 48 lbs. per square foot, the wind travelling with a

velocity of 80 miles per hour. This was quite a hurricane in

intensity if we take 10 lbs. per square foot as equal to a strong

gale.

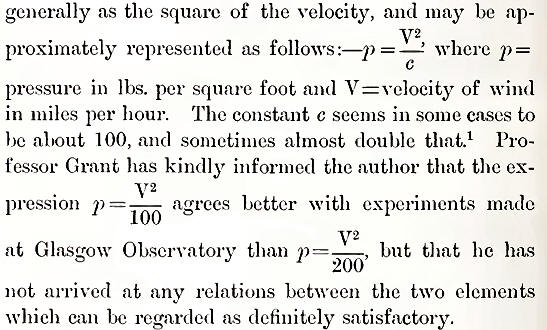

Sometimes the nature and velocity of the wind are

given in tables with the corresponding pressures. Thus, a “ light

breeze ” has a velocity of about 7 miles per hour,

and giving a pressure of about a £ of a lb. per

square foot of vertically-exposed surface. A “fresh breeze” is

double this velocity, but the pressure is now four times what it was

at 7 miles. A “strong breeze” is about 20 miles per hour: “gales”

range from 25 to 45 miles per hour; whilst storms and hurricanes

rise beyond this to as much as from GO to over 100 miles per hour,

with wind pressure of 20 to GO lbs. per square foot. The pressure

varies

The very heavy storms which come upon our coasts

appear to partake more or less of the character of cyclones, as from

the tendency to veer in varying directions during the time of blow,

a distinct rotatory and progresi

sive motion is indicated. This veering tendency is

sometimes marked in heavy storms by the direction of fallen timber,

in some cases one tree lying across another, showing the movement of

the wind.

The great and memorable storm in which the Tay Bridge

fell began on the west coast as a strong south wind about 2 p.m.,

and gradually shifted round to west and north-west, increasing in

intensity till about 7 or 8 p.m., when it decreased.2 The

law of such storms has now been ably investigated, and instructions

drawn up for the guidance of the mariner at sea, showing how he

should steer to get out of the spiral or circle of storm influence.

The herring fishing industry in the Firth of Clyde

has long been an extensive one, and the fame of the Loch Fyne

herring is known far and wide. The migratory tendencies of this fish

are but little known; but the quality and size appear to vary in

some measure with the locality around our coasts where the shoals

congregate, the distinctive characteristic of the Loch Fyne herrinir

beint; its delicate flavour and small size. This industry, like all

fishing more or less, varies much in its results. Thus the quantity

of herrings cured on the west

coast in 1SS6 was about 170,000 barrels; whilst in

18S5 there were as many as about 254,000 barrels. Although such a

great difference is seen in the total, yet it appears that on some

parts of the coast, such as Kilbrannan Sound, the fishing was

prosperous in 1S86.

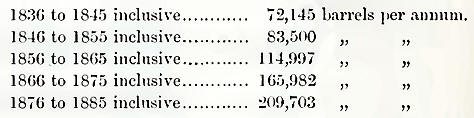

The following yearly average from published

statements shows for a period of fifty years back the quantity of

herrings cured in the west of Scotland:—

The herring fishing is prosecuted in the Firth of

Clyde by means of wherry-rigged half-decked boats of G or S tons,

and by smaller boats carrying lug sails. The drift nets are shot

about sundown, and drawn about sunrise. The system of trawling is,

however, now much in vogue, and has largely displaced the drift-net

fishing; but in the opinion of some of those who should know, the

herring caught by the trawl method are inferior to the drift-net

herring, as the blood does not get out at the gills as when caught

in the mcsli. The herring fishing in the firth commences in June and

used to end in January, but is now sometimes carried 011 to March.

On looking over the fishery statistics, it is most

astonishing to note the quantity of fish of all kinds taken around

our coasts and the value of this sea harvest. Thus for one month

only (September, 1887), the total value of the fishing around the

Scotch coasts was over £123,000, and of this the herring value was

fully one-half, or over £66,000. Haddocks were nearly one-half of

the herring value. Of this fishing the east coast share was by far

the largest, the value of the herring caught there being about

£40,000. Shetland and Orkney had the high figure of £12,000, and the

west coast £14,000. Of this the Firth of Clyde gave £12,000 alone.

It appears that the value of the fish of all sorts landed on the

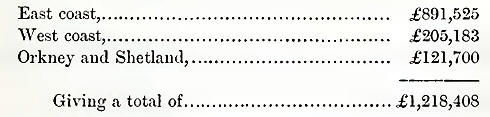

Scotch coasts during the ten months ending 31st October, 1887, was:

Dr. John Murray, of the Challenger expedition, in

speaking of the feeding grounds of the herring and salmon, says that

the ridge, 25 fathoms from the surface, which separates Loch Fyne

from the ocean, causes a marked difference between the well-known

herrings of that loch and those of the outside western lochs. Dr.

Murray believes that the Loch Fyne herrings do not quit the loch at

all, but that after spawning they go down to the deep water of the

loch and remain there feeding in quiet, rising afterwards to the

warmer waters of the surface for the purpose of spawning. Their food

appears to be prawns and small crustaceans, and it is due to the

superior feeding at the bottom of the loch that these herrings owe

their characteristic quality. Oysters beds do not flourish on the

Firth of Clyde; but the mussel beds are valuable, the famous mussel

banks opposite Port-Glasgow being well known; |