|

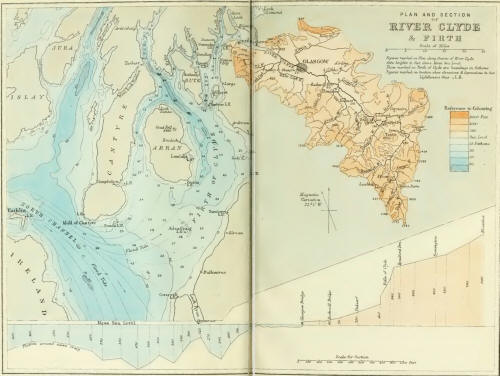

From its source downwards to Glasgow the Clyde flows

through Lanarkshire; afterwards, until about Greenock, its course is

between Dumbartonshire on the north and Renfrewshire on the south.

The fertile slopes of Ayrshire and the Highland hills of Argyleshire

continue the boundary to the now widening waters of the Firth.

Lanarkshire, or Clydesdale, is bounded on the north

and north-west by the counties of Stirling, Dumbarton, and Renfrew;

on the north-east by Edinburgh and Linlithgow; on the east by

Peebles; on the south by Dumfries; and on the south-west and west

by Ayrshire. It is situated between 55° 54' and 55° 25' of north

latitude, and 3° 25' and 4° 18' of west longitude. The length from

north-west to south-east is about 50 miles; and the greatest breadth

from north-east to south-west is 34 miles. It contains an area of

568,867 acres, or 888 square miles.

Lanarkshire is subdivided into three districts,

called the Upper, Middle, and Lower Wards. In the Upper Ward, of

which Lanark is the chief town, are the parishes of Carluke, Lanark,

Carstairs, Carnwath, Dunsyre, Dolphinton, Walston, Biggar, Liberton,

Lamington and Wandell, Coulter, Crawford, Crawfordjohn, Douglas,

Wiston and Roberton, Symington, Covington, Pettinain, Carmichael,

and Lesmahagow. The Middle Ward, of which the town of Hamilton is

the centre, comprehends the parishes of Hamilton, Blantyre, East

Kilbride, Avondale, Glassford, Stonehouse, Dalserf, Cambusnethan,

Shotts, Dalziel, Bothwell, New Monkland, and Old Monkland. The Lower

Ward contains the parishes of Cadder, Cambuslang, Rutherglen,

Carmunnock, and part of Govan and Cathcart. In and around Glasgow

are the parishes of the City, Barony, Calton, Gorbals, Mary-hill,

Springburn, and Shettleston.

Dumbartonshire, in old times known as The Lennox, is

more or less mountainous, with some arable land near the Clyde. Loch

Lomond stretches for miles towards the Highland mountains, and the

“Lofty Ben Lomond,” over 3000 feet in height, rises from the eastern

side of the loch, seen from afar, whether from Highland hill or

Lowland vale. The area of this county is 172,677 acres, of which the

waters of Loch Lomond itself form nearly one-eighth part. The town

of Dumbarton, famous for its ship-building enterprise, is the

principal industrial centre.

Renfrewshire extends to 162,427 acres, and is much

diversified as to soil, minerals, towns, &c., and, like Lanarkshire,

contains many important industrial centres of population. From the

returns for 1887-88 the valuation of Lanarkshire appears to be

£2,079,860.

Several important tributary streams enter the Clyde

along its course, and are associated with many circumstances and

places of interest. Wilson, in his Clyde poem, enumerates these

streams, giving each its particular characteristic, thus:

“Glengonar’s dangerous stream was stained with

lead;

Fillets of wool bound dark Duneaton’s head ;

With corn-ears crowned, the sister Medwins rose,

And Mouse, whose mining stream in coverts flows;

Black Douglas, drunk by heroes far renowned,

And turbid Nethan’s front with alders bound;

Calder, with oak around his temples twined,

And Kelvin, Glasgow’s boundary flood designed;

Cart’s sombre stream, which deep and silent moves,

Where kings and queens of old indulged their loves;

Leven, which growth and infancy disdains,

Rushing in strength mature upon the plains.”

John Wilson was born near Lanark in the year 1720. He

wrote several pieces of a descriptive and dramatic character. His

poem of “The Clyde” was published in 1761. Wilson afterwards was

appointed to the Grammar-school of Greenock in 1767, under the

condition that he would give up “the profane and unprofitable art of

poem making.” This was a sore blow to the poet, but he accepted the

position, and devoted himself closely to his work, which he carried

on till within a year or two of his death in 1789.

Allan Ramsay was a native of Leadhills, where he was

born just about two hundred years ago. As described by himself:

“Of Crauford-muir, born in Lead-hill,

Where mineral springs Glengonir fill,

Which joins sweet flowing Clyde,

Between auld Craufurd-Lindsay’s towers,

And where Deneetnie rapid pours

His stream through Glotta’s tide.”

He afterwards went to Edinburgh, where, amongst many

pieces, his “Gentle Shepherd” was published in 1725. He died in

Edinburgh in 1757, aged 78.

Taylor and Symington, who were associated with the

first attempts at steam navigation made by Patrick Miller of

Dalswinton just a century ago, were also natives of this district.

Lanark is an ancient town and royal burgh, situated a

few miles north of the Clyde. According to some it was a seat of

royalty and the home of an early parliament in the tenth century.

Its associations with the patriot Wallace in his early struggles are

graphically portrayed in the Scottish Chiefs, and it was doubtless

one of the many points in the Roman system of military ways which

passed down the Clyde valley at the eastern end of the town.

A local guide-book states that “Lanark formerly

enjoyed the privilege of keeping the standard weights of the

kingdom. These weights were stamped with a spread eagle with two

heads, the arms of the burgh. In 1790 they were measured by

Professor Robison of Edinburgh, and a second time (about 1800) for

the purpose of rectifying those of Edinburgh.”

Here the ruins of the church of St. Ken Bern, dating

from the early part of the twelfth century, are interesting as an

example of the "Early English” architecture. The Lee Aisle is

attached to the building, and a number of quaint old tombstones may

be seen in the cemetery, together with a handsome monument erected

to the martyrs who suffered for conscience sake and belonged to the

district.

Sir Walter Scott, in his tale of the Talisman, tells

us that this talisman was an amulet supposed to possess special

healing virtues, and which was brought from the East in the

fourteenth century by Sir Simon Lockhart of Lee and Cartland, who

“left it to his heirs, by whom, and by Clydesdale in general, it

was, and is still, distinguished by the name of the Lee-penny, from

the name of his native seat of Lee.”

The history of bells is always curious and

interesting. One of those in the spire of the parish church has been

recast several times, the earliest date on it being 1110.

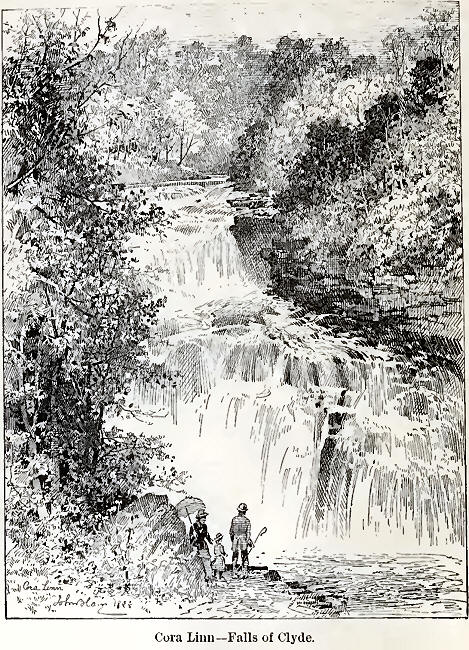

One of the principal tributary streams of the Clyde

is the Douglas Water, an important stream, draining the large

district to the south of Lanark and the Falls of Clyde, and lying to

the west of Tinto. The beautiful and fertile valley through which

this stream flows is called Douglasdale, the parish of Douglas

extending from the Clyde for about 12 miles. The parish is said to

take its name from the stream, Douglas signifying a dark colour, and

which appears to have given the surname of Douglas to the family who

so powerfully affected the history of Scotland in earlier days.

Douglas Castle, the “Castle Dangerous” of Sir Walter Scott, played,

like other strongholds, an important part in the War of

Independence, and he states that its surrender by the English about

the year 1306 “was the beginning of a career of conquest which was

uninterrupted until the crowning mercy was gained in the celebrated

field of Bannockburn.”

The Mouse enters the Clyde on the right bank a short

distance below Lanark. It is principally noticeable from the bold

and striking scenery near its point of junction with the river,

where it flows through the chasm of the Cartland Crags, spanned by

Telford's viaduct carrying the Glasgow road. Writing of Telford’s

works in roads and bridges, Smiles says: “Owing to the mountainous

nature of the country through winch Telford’s Carlisle and Glasgow

road passes, the bridges are unusually numerous and of laro-e

dimensions. Thus the Fiddler’s Burn Bridge is of three arches, one

of 150, and two of 105 feet span each. There are fourteen other

bridges, presenting from one to three arches, of from 20 to 90 feet

span.

But the most picturesque and remarkable bridge,

constructed by Telford in that district, was upon another line of

road subsequently carried out by him, in the upper part of the

county of Lanark, and crossing the main line of the Carlisle and

Glasgow road almost at right angles. It was carried over deep

ravines by several lofty bridges, the most formidable of which was

that across the Mouse Water at Cartland Crags, about a mile to the

west of Lanark. The stream here flows through a deep rocky chasm,

the sides of which are in some places about 400 feet high. At a

point where the height of the rocks is considerably less, but still

most formidable, Telford spanned the ravine 129 feet above the

water.”

The Netlian enters the Clyde on the left below

Stone-byres Fall. It flows through the parish of Lesmahagow (famous for its gas-coal), and not far from its

junction passes through a rocky gorge, on the top of which stands

the ruins of Craignethan Castle, believed to be the prototype of the

Castle of Tillietudlem in Old Mortality-A considerable extent of

Silurian rocks are met with in this district, some of the

characteristic Lingula fossils being found in the rocks of the

Nethan.

Ordnance survey and Ordnance datum are well-known

terms, especially the former, the latter belonging more specifically

to the province of the engineer. We often speak of differences of

levels of places and compare their heights; and if we look over the

Ordnance maps, which indeed so well repay careful study, we see not

only the country mapped out with accuracy, but we also find certain

figures dotted over the surface, showing the elevation of the land

above the fixed mean water datum at Liverpool. [This datum is a

point 4'67 feet above the level of the old Dock Sill, Liverpool.] The principles

underlying such a survey as that which has been carried out in this

country depend upon the science of spherical trigonometry, and are

more or less complex in their applications to the necessary

refinements entered into by the officers of the Survey. It may be

interesting, therefore, to note that a native of the parish of Carluke (General Roy) appears to have been the first surveyor who

carried out the earlier measurements of the base-lines required.

Thus, in a recent notice the Glasgow Herald, referring to the work

of General Roy and others about a century ago, says: “General Roy,

apart altogether from later labours, may be said to have originated

the Ordnance Survey as we now understand the phrase. It is pleasant for

west-country people to remember that this distinguished military

engineer was a native of Carluke parish, Lanarkshire.”

The Aven or Avon, doubtless from the British word for

river, flows into the Clyde at Hamilton, and drains a good extent of

country to the south. As it approaches the neighbourhood of Hamilton

it finds its way through the fine old woods of Cadzow, whose old

oaks, after braving the “battle and the breeze” of a thousand years,

are, many of them, still flourishing, and likely to see many more

changes in the coming years. Their battles have been mainly with the

elements and the somewhat varying conditions of climate throughout

the long centuries of their life; but they have struck root firmly,

and borne themselves nobly and bravely against the winds and frosts

of winter, and the no less trying droughts of summer. Some old

veterans there are, hollowed out by time, into whose shelter we can

gather; and as we stand within the oak walls, with their still

vigorous foliage floating high above us, we seem to hear them

whispering to one another old stories of the past, when the wild

animals and their Caledonian hunters roamed beneath their branches,

and the excitement of the chase or the din of war echoed through the

far-stretching glades. Later on the merry hawking party with

knights, ladies, and attendants, clad in the armour and gay attire

of the middle ages glanced amidst the sombre depths of this forest,

and in times nearer to our own, persecuted Covenanters sought

shelter amid its friendly covering. And here, even yet, under these

old oaks, we have a remnant of the wild denizens of the primeval

forest in the white cattle quietly feeding there. Cadzow, and

Chillingham in England, seem to be the only places where the old

breed of wild cattle now exists.

They are of a white colour with black muzzles, and

appear still to retain traces of the wild and untamable spirit of

their far-back ancestors of the Caledonian forest.

After passing the Avon we find three different

streams bearing the name of Calder as tributaries, two of which flow

in on the north side, and one on the southern side of the river. As

the wordCalder is said to indicate a place of wood and water, it is

not strange that it should be applied to several of the well-wooded

streams of this district. The South Calder Water is distinguished

for its fine semicircular arch, supposed to he of Roman origin, as

it is on the line of the Roman road which ran along the north side

of the Clyde.

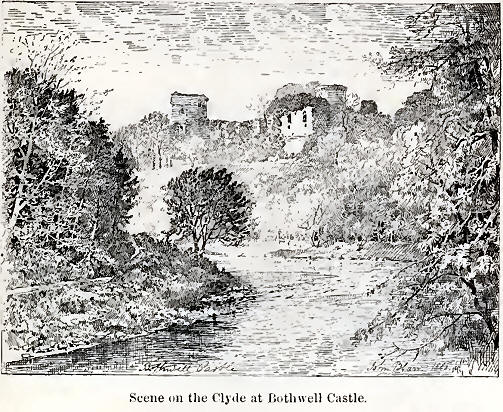

A short distance below is the village of Bothwell

with its curious old church, thus described in

the Statistical Survey of Scotland:—

“The Old Church of Bothwell is a very ancient

structure, and presents a fine specimen of Gothic architecture. It

was used in former times as the quire of the collegiate church of

Bothwell. In Catholic times Bothwell was the most important of the

five collegiate churches of Lanarkshire. It was established by

Archibald Douglas, Lord of Galloway (who married Johanna Moray,

heiress of Bothwell), 10th October, 1398, and was confirmed by a

charter from the king, 5th Feb. 1398-9. It was about this period

that the present quire was built. The master-mason, as was indicated

by an inscription in Saxon letters on a stone near the outer base of

the old steeple, now removed, was Thomas Tron. The roof is arched

and lofty, and presents the most remarkable feature of the building.

On the outside it is covered with large flags of stone, hewn into

the form of tiles resting on a mass of lime and stone, which in the

centre is 11 feet in depth. The side walls are strengthened by

strong buttresses to support the weight of the roof.” The new parish

church was built in 1833, and is in the Gothic style, to harmonize

with the old church to which it is attached, a handsome tower, 120

feet high, rising at the junction of the two buildings. Joanna

Baillie, celebrated as an authoress, was born in Bothwell Manse, her

father, the Bev. James Baillie, D.D., being minister of the parish.

The Calder—sometimes called the Rotten Calder—rises

in the trap-hills to the south of Kilbride, and flows more or less

northwards through a district of much geological interest and

picturesque beauty. Both coal and ironstone have been worked along

the bed of this stream, the old entrance workings being still

visible. Cement-stones and limestones, both commercially valuable,

are worked at different parts of its course. One feature of special

interest to geologists is that in passing along in its course from

the hills to the Clyde it crosses the great “fault,” which runs more

or less parallel to the valley of the Clyde, and extends more or

less from the Nethan, near its confluence with the Clyde, to about a

mile or so to the south of Glasgow Bridge.

There is still another Calder flowing from the north

and joining the Clyde almost opposite the Rotten Calder, below

Uddingston.

The Kelvin is an important tributary of the Clyde,

draining1 a considerable area from its source In the Kilsyth Hills

till it falls into the river at Partick. Its course is interesting,

as at several points it is not far from the line of the Roman Wall,

and at Belmulie, a few miles north of Glasgow, it crosses a point

where at one time a Roman station was placed.

The Cart enters the Clyde on the south side, a few

miles farther down, passing to the west of the ancient burgh of

Renfrew, and not far from Inchinnan, whose religious church history

dates back to 1100—a grant to the Knights Templars being made at

that time by David I. Two considerable streams—the White Cart and

Black Cart—meet just a little above their junction with the Clyde,

the Black Cart having been, shortly before the junction,

supplemented by the waters of the Gryfe. These streams drain a large

extent of country from their sources in the high hill ground

bordering the southern valley of the Clyde, passing through

well-cultivated and populous districts, abounding in fine scenery

and varied associations, both of an antiquarian and commercial

character.

The White Cart rises in the Mearns district, eleven

miles south of Glasgow, and flows at first in a northerly direction,

passing through the parish of Cathcart and near the ruined castle of

the same name. Within a short distance is the field of Langside, the

battle fought there in 15G8 being so disastrous to the unfortunate

Queen

Mary of Scotland. This stream then turns westwards,

passing through the populous and industrial centre of Pollokshaws,

and shortly afterwards near the now ruined Crookston Castle, a

residence of the same ill-fated Queen in her earlier days. Flowing

through the busy town of Paisley, the White Cart turns again

northwards until it joins its brother with the dark cognomen, which

latter rises in Castle Semple Loeh, and flowing north-easterly is

joined by the Gryfe Water, which rises on the western side of

Renfrewshire behind Greenock, and flows through a long valley lying

amongst the hills. The head-waters of the Gryfe are utilized for

supplying the town of Greenock with water, and at Bridge of Weir a

dam is thrown across to give water-power to the mills there.

Campbell sings of the Cart:—

“Oh, the scenes of my childhood and dear to my heart,

Ye green waving woods on the margin of Cart!

How blest in the morning of life I have strayed

By

the stream of the vale and the grass-covered glade!”

Paisley appears to be situated on or near the site of

the old Roman station of Vanduara, and has for long been a

prosperous town, both in the early days of the hand-loom weaving

industry, and later on when water-power and steam gradually

superseded the use of hands, and the single work-room of the weaver

was extended and enlarged to the factory with its looms and

spinning-jennies for the manufacture of various fabrics. Now the

great thread-mill, where miles of that indispensable material for

sewing, whether by hand or by machine, is made, may be seen rising

as a palatial-looking structure many stories high. Our old friend

Pennant, always keenly alive to facts and objects of interest, tells

us that, “about fifty years ago the making of white stitching

threads was first introduced into the west country by a private

gentlewoman, Mrs. Millar of Bargarran, who, very much to her own

honour, imported a twist-mill from Holland and carried on a small

manufacture in her own family.” This early and simple attempt was

afterwards extended, and at the time of Pennant’s visit the value of

the thread manufacture had risen to nearly £50,000. Besides this the

manufacture of lawns, silk gauze, and ribbons, was carried on, and

the celebrated Paisley plaid, with its well-marked pine-cone

pattern, became quite a fashion. Some of these latter industries

have died out, but their place has been taken by others, and

Paisley, with her 66,000 inhabitants, is as busy as ever

manufacturing, besides thread and some other textile fabrics,

starch, corn-flour, and machinery, while on the banks of the

tributary Cart iron vessels of various kinds are now built.

Paisley has a long list of eminent men who have been

born within her borders. Professor Wilson, the “North” of

the Nodes; Wilson, the ornithologist; and the sweet singer, Tannahill, whose home is still shown where he worked at his loom;

many others whose names are celebrated were natives of this busy

industrial centre.

The Abbey Church is a fine old building, the style

being early English Gothic. Adjoining the church is a building

called the Sounding Aisle, from the wonderfully fine echo or

reverberation of sound which takes place inside. On shutting the

door suddenly the noise is intensified to such an extent as to

resemble a peal of thunder. The sound of a strong, deep voice is

answered by as it were the roar of a lion. Singing, especially low,

clear tones, and whistling, can be heard wandering away about the

roof as if there were answering spirits hovering above.

Passing down to Renfrew, another ancient burgh, we

are in the neighbourhood of Elderslie, where at least one tradition

says that the patriot Wallace was born.

“Yet bleeding and bound though her Wallace wight

For

his long-loved country die,

The bugle ne’er sung to a braver knight

Than Wallace

of Elderslie.”

Renfrew was an important place in early times, and

was frequented by royalty. Robert II. had a palace here, and, as

showing the condition of the river at these times, it is said that

in the sixteenth century the burgesses of Renfrew had sixty boats

employed fishing salmon. These fish, indeed, were so plentiful that

the apprentices in the ancient and royal burgh made a stipulation

that they were only to have a certain number of salmon dinners. Now,

a rail way-station, a steamboat wharf, and ship-building yards, are

the most striking features which attract the eyes of the visitor. It

may be noted that the building of dredgers is made a specialty here,

all the newest improvements being introduced, so as more readily to

scoop up and remove the dredged material from the river or bank. It

is not only in our own river that dredging operations are carried

on, but in many other rivers at home and abroad, and on the bars at

their mouths, the iron bucket tears its way and brings up its spoil.

Inchinnan parish church stands a little below

Renfrew, beautifully situated on a bend of the Gryfe close to its

junction with the Cart. A religious house existed here so far back

as in the year 1100; and in the graveyard several quaintly-carved

old stones may be seen.

The following anecdote is told to show the effect on

an upper Clydesdale man of the tidal action in the river here. "In

the early part of last century the clergyman of Lamington, in the

upper ward of Lanarkshire, had come to assist his friend, the

incumbent of Inehinnan, on a sacramental occasion, travelling on

horseback, and attended, according to the invariable practice, by

his man, who, although from his vocation a severe critic of sermons,

was profoundly ignorant of the doctrine of the tides. During the

course of the visit the servant was astounded and alarmed to

discover that the waters were moving in a direction the reverse of

what he had previously witnessed; whereupon, concluding that some

awful calamity impended, he hastened to his master’s chamber, broke

his slumbers, divulged the appalling phenomenon, suggested the

prudence of immediate departure, and concluded by expressing a faint

hope that they might yet reach Lamington in safety.”—Statistical

Survey of Scotland.

The water from Loch Humphrey in the Kilpatrick Hills

is perhaps the largest addition for some distance on the north side,

if we except the Forth and Clyde Canal, which empties itself at

Bowling. The stream referred to was largely utilized some years ago

by the mills at Duntocher erected there. A little above this village

the stream crosses the line of the Roman wall, where an old arch,

probably of Roman origin, still carries the roadway leading to

Glasgow by New Kilpatrick, and contains a stone with an inscription

in Latin, which appears to be a copy from an earlier part of the

structure. A mile or two lower down the river the small village of

Milton is situated in a hollow almost beneath the shadow of the

great basaltic hill of Dumbuck. This place, and Rothesay in the

island of Bute, have the honour of being the first to start the

cotton industry by power.

The Leven, also on the north side, is a short river,

being the outlet of the waters of Loch Lomond. It is not now the

stream of which Smollett wrote, as its banks are alive with various

industries, such as dyeing, printing, ship-building, &c.

“On Leven’s banks, while free to rove,

And tune the rural pipe of love,

I envied not the happiest swain

That ever trod the

Arcadian plain;

Devolving from thy parent lake,

A charming maze thy waters make,

By bowers of birch and grove of pine

And edges

flowered with eglantine.”

Dumbarton, situated at the foot of its guardian Rock,

has, like many other Scottish towns, a history stretching back to

the rude and troublous times of centuries ago; thereafter, as the

country quieted down, sharing in the manufacturing and commercial

progress of the times, due to the enterprise and skill of its

townspeople. At an earlier date it was noted for its glass

manufacture; now the specialty is ship-building and marine

engineering. The Dumbarton people appear early to have shown skill in the ship-building line, as it is said that a

ship was built here for King Robert the Bruce, who, after “life’s

fitful fever,” died at Cardross in the neighbourhood.

Pennant says, “The Roman fleet in all probability

had its station under Dumbarton; the Glota or Clyde has there

sufficient depth of water; the place was convenient and secure, near

the end of the wall, and covered by the fort of Dunglas; the Pharos

on the top of the great rock is another strong proof that the Romans

made it their harbour, for the water beyond is impassable for ships

or any vessels of large burden.”

From Dumbarton many fine steamers and sailing vessels

have been launched into the Leven, and its various shipbuilding and

engineering yards employ many thousands of workmen. And not only is

the practical department of ship-building so well represented, but

this town has the honour to possess a special feature, unique on the

Clyde, viz.: a tank, erected by the Messrs. Denny in the Leven

Shipyard, in which models of the various ships about to be built can

be experimented upon, and the results for the ship obtained from the

experiments with the model by means of the relations established by

the late Dr. Froude, whose tank at Torquay has yielded so many

results alike valuable to the ship-builder and the marine engineer.

From Pennant’s tour we learn that: “After a long

contest with a violent adverse wind, and very turbulent water,” he

passed under on the south shore, Newark, a castellated house with

round towers, and reached Port-Glasgow. He says it is “a

considerable town with a great pier, and numbers of large ships,

dependent on Glasgow, a creation of that city since the year 1608,

when it was purchased from Sir Patrick Maxwell of Newark, houses

built, a harbour formed, and the Custom-house for the Clyde

established.”

Port-Glasgow, with its many old-fashioned houses with

crow-stepped gables, and its distinctive odour to the passerby in

the railway train of tar or oakum from the rope-spinning works,

recalls the past times when there were few or no steam-boats and no

electric telegraph, and the sailing ship was the great ocean

carrier. The merchant in those days, after sending off his ship and

cargo, could rest contentedly, so far as these possessions went, and

was not worried, as his successor is at the present time, with swift

passages and “wires” from all quarters of the globe. This town was

originally called New Port-Glasgow, or shortly “Newport;” at least,

Wilson, about 1764, refers to it thus:

“Where, crowned with wood, fair hills embrace the

bay

Where Newport smiles, in youthful lustre gay.”

Ground was originally feued here by the magistrates

of Glasgow for a harbour for the shipping of the city. The Glasgow

people had at first thought of Dumbarton and then Greenock as their

port; but difficulties with the authorities of these independent

burghs caused them to set up one for themselves, hence Port-Glasgow.

Greenock, like the larger commercial city further up

the river, was but a comparatively small town about the middle of

last century, the population at that time being-under 4000. Looking

at a map of the river and firth published in 1760 by John Watt,

junr.,1 we see Greenock and the neighbouring town of Cartsdyke

(now long since united) as each clustered round their quays or

harbours, which project boldly into the river like bent arms, as if

to it el come and secure the passing sail.

Greenock, according to Dr. Leyden in 1767, was a “thriving seaport, rapidly emerging into notice. In the beginning of

last century it consisted of a single row of that died houses,

stretching along a bay without a harbour. In 1707 a harbour began to

be constructed, but the town increased so slowly that in 1755 its

population amounted only to about 3800 souls.'' In 1785 a dry-dock

was built, and from time to time the harbour accommodation improved,

so that about 1829, when the population amounted to about 27,000,

the length of quays was over 700 yards. The Custom-house was erected

in ISIS at a cost of £30,000, and with its handsome classic front

has long been a well-known object to the steam-boat travellers up

and down the river, and especially in the old days before the

Princes Pier and Wemyss Bay routes were opened. Many a hurried, and

perchance wearied, foot has trod the narrow and dirty lane which

used to lead from the railway terminus to the quay, passing this

tine edilice on the way. But not only has the march of improvement

in railway service been going on. it has also passed over the quaint

old crow-stepped gabled houses of this part of the town, and new

buildings in all the glory of fresh ashlar fronts have arisen in their place. A few years

ago a handsome group of buildings, with an elevated tower, were

erected for the municipal work of the town.

In the Statistical Survey of Scotland we have the

following curious extract:—

“In the Literary Rambler for October, 1832, there

are some curious excerpts from a manuscript in the Advocates’

Library, purporting to be a report by Thomas Tucker, one of

Cromwell’s servants, who was appointed to arrange the customs and

excise in this country; from which we may form some conception of

the state of commerce in Greenock and the neighbouring towns two

centuries ago. The report is addressed ‘ To the Right Honourable the

Commissioners for Appeals,’ and is dated November 20th, 1656. After

describing Glasgow as a ‘very neate burghe towne;’ all whose

inhabitants were traders except the students, ‘ some for Ireland,

with small smiddy coales in open boates from four to ten tonnes some for France with pladding, eoales, and hering.’ And some

venturing as far as Barbadoes, but discouraged by the loss they

sustained, ‘by reason of their going out and coming home late every

year.’ The reporter proceeds to describe the towns of Port-Glasgow

and Greenock in the following terms: ‘The number of ports in this

district are, 1st, Newarke (Port-Glasgow), a small place where there

are (besides the laird’s house of the place) some four or five

houses, but before them a pretty good roade, where all the vessells

doe ride, unlade, and send their goods up to the river Glasgow in

small boats; and at this place there is a wayter constantly

attending. 2dly, Greenock—such another—only the inhabitants are

more, but all sea men or fishermen trading for Ireland or the isles

in open boates. Att which place there is a mole peere where vessells

in stresse of weather may ride and shelter them selves before they

pass up to Newarke; and here, likewise, is another wayter.’ ”

Greenoek, with a population of about 70,000, is a

busy commercial centre. Ship-building, marine engineering,

iron-foundries, and sugar-works, all combine to give employment to

large numbers of work people. In busy times the smoke from the many

tall chimneys, although indicating commercial activity, has quite an

obscuring effect on the splendid landscape which opens out to the

passerby on the railways carried along the steep hill-sides above

the town.

The Shaws Water-works, for supplying Greenock with

water, were designed by Mr. Robert Thom, who had so successfully

carried out the water-power required for the Rothesay cotton-mills,

by laying various loehs under contribution, and regulating the

supply in the various channels by self-acting sluices. Mr. Thom

reported in 1824 on the Greenock supply, showing the great value of

the power which could be obtained. Mr. Thom was so impressed by

these advantages, that he says, “Here you would have no

steam-engines, vomiting smoke, and polluting earth and air for miles

round, to the no small annoyance and discomfort of the community at

large, and to the unspeakable vexation and chagrin of gardeners,

bleachers, and washerwomen.” Mr. Thom afterwards says: “It is not to

be inferred from this that I think lightly of the steam-engine. I

merely wish to draw a little attention to another source of national

wealth, which (perhaps obscured by the dazzling blaze that has so

long encircled the inventions of Watt) has been hitherto almost

totally neglected. Such, indeed, has been the eclat of the

steam-engine, that whenever a work became scarce of water, either

from its being enlarged or from a dry season, nothing was to be

heard but the general cry: ‘Put up a steam-engine, and be

independent of water.’ ” Mr. Thom, however, thought that the cry

would soon change to, “ Get water if you can, and down with your

steam-engines.” He, however, acknowledges the importance of his

rival, especially for navigation, and concludes by saying, “Nor

shall the name of the less fortunate inventor of the steam-boat be

ultimately lost to fame, for although a thoughtless public should

allow him to linger out the evening of his days in poverty, yet the

time is coming when public meetings will be held and monuments

erected to the memory of Henry Bell.”

Harbours and docks present an inviting water-way and

secure retreat for the various ships freighted with merchandise from

all quarters of the globe, and from the fine esplanade carried along

the shore to Fort Matilda a splendid view is afforded of the busy

river, with its variety of shipping, the outward and inward bound

Altantic liners at the Tail of the Bank, and the distant Highland

hills beyond the Kilcreggan shore. The range of the tide at Greenock

being small, from 8 to 10 feet, docks inclosed with locks or gates

were not so much required as in ports having a greater range.

Several of the docks or harbours are therefore open to the river.

Greenock, in its prosperity, has not forgotten the

poor and the aged. A large and well-appointed building to the west

of the town, called Wood’s Mariners’ Asylum, was founded in 1850 by

Commissary-General Sir Gabriel Wood, for the benefit of aged

merchant master-mariners and merchant seamen, natives of the county

of Renfrew and neighbourhood. Hospitals and Infirmaries, Charity

Schools, a Seamen’s Friend Society, homes for destitute boys and

girls, and many other benevolent undertakings, all go to show that

the present age, marked out as it is by the splendour of commercial

success and scientific skill, is yet especially noticeable above the

ages which have passed away as one of individual and public

benevolence. Greenock has also several scientific institutions, one

of which, the “Scientific Library,” was founded by James Watt in

1816. |