|

The traveller by the Caledonian Railway after passing

Carstairs finds himself rising rapidly as he enters the mountainous

district to the south. On the right the fine conical form of Tinto

stands like a guardian of the pass. As he speeds onwards the valley

narrows, with great swelling hills on either side. The river Clyde,

which the line crossed shortly after leaving Carstairs, is once more

alongside, and as the iron horse speeds his way upwards the long

train dashes across the winding stream, which is now seen hurrying

onwards with more rapidity than when it was first met lower down,

where it lazily moved among the meadow-lands.

A well-made road is also observable, being the old

mail-coach route to Carlisle. This road was laid out by Telford, a

celebrated engineer of nearly a century ago, who, from being a

shepherd boy on the slopes of the Eskdale Hills, rose to design some

of the most important engineering works carried out at the

commencement of the present century. As a road-maker Telford was a

worthy successor to the old Roman engineers who have left so many

records of their skill and enterprise throughout our country. The

present road from Carlisle to Glasgow is pretty much in the line of

the early Roman road which passed north from the termination of

Hadrian’s Wall at the Solway to the Wall of Antoninus between the

Clyde and the Forth. Branches from this road ran down the Clyde

Valley to the termination of the latter wall, and passing over the

site of Glasgow, reached the Roman station situated near the town of

Paisley, which is supposed by some to be the Vanduara of the Romans.

The road, rail, and river are all at this point close

alongside one another in the narrow valley. It is not until an

elevation of about 1000 ft. is reached that the river parts company,

and winding along an upland valley to the right, stretches away like

a silver thread into the dark and misty recesses of the Lowther

Hills. Curiously enough, this longer terminal feeder of the stream

we have been following does not carry the name we know it by farther

down, but a shorter branch coming from the hills to the left, called

Clydes Burn, is sometimes spoken of as the source of the Clyde. The

longer branches, called the Powtrail and Daer Waters, flow from the

amphitheatre of hills bounded by Queensberry Hill to the south; of

these branches the Daer Water is the more important feeder.

According to the Ordnance Survey the river Clyde is first known by

that name after the junction of the Powtrail and Daer Waters.

The course of the Clyde is at first in a northerly

direction, after which it trends to the east, and passing near

Biggar, wheels round in a roughly-semicircular curve. It then starts

off in a north-westerly course, which it more or less keeps until,

reaching the Firth of Clyde at Greenock, its waters flow seawards in

a southerly direction. The length of the river from its source to

below Greenock, where the Firth of Clyde begins, may be taken at 100

miles, and the total fall or difference of level between the same

points is about 2000 ft. The area of the basin or prolonged valley

through which its course flows is about 1600 square miles.

Throughout this course great variations of fall occur, notably at

the Falls of Clyde, where the total difference of level from above

Bonnington to the foot of Stonebyres Falls is 350 feet.

The sources of the Clyde, lying as they do about the

centre of the southern part of Scotland and amongst the high hills

south of Tinto and around the Moffat district (some of which rise to

2G00 and 2700 feet above the level of the sea), are naturally

associated with other waters which also in their turn play an

important part in the topography of the district, and many of which

are immortalized in Border song and story. Thus within a short

distance of the so-called springs of the Clyde, and on the other

side of the hills to the eastward, rises the classic Tweed, and not

far to the east and south the important tributaries of the latter,

the Yarrow, Ettrick, and Teviot; whilst just over the summit level

the Annan darts away to the south, making for the far-distant and

blue outline of Skiddaw beyond the wide and rapid Solway.

Tributaries of the Nith flow towards the south-west

from the western sides of the hills bounding the valley, and on the

western side Don Mas Water flows northwards, joining the Clyde

itself west of Tinto.

Wilson, in his poem of “The Clyde,” thus describes

the surroundings:

“From one vast mountain bursting on the day,

Tweed, Clyde, and Annan urge their separate way.

To Anglia’s shores bright Tweed and Annan run,

That seeks the rising, this the setting sun.”

The district around the upper waters of the Clyde is

wild and bleak, and across the hills on the western side lies the

Enterkin Pass, thus described by Defoe:

“From Drumlanrig I took a Turn to see the famous Pass

of Enterkin or Introkin Hill: It is indeed not easy to describe; but

by telling you that it ascends through a winding Bottom for nearly

half a Mile, and a Stranger sees nothing terrible, but vast high

Mountains on either Hand, tho’ all green, and with Sheep feeding on

them to the very Top; when, on a suddain, turning short to the left,

and crossing a Rill of Water in the Bottom, you mount the Side of

one of those Hills, while, as you go on, the Bottom in which that

Water runs down from between the Hills, Keeping its Level on your

Right, begins to look very deep, till at Length it is a Precipice

horrible and terrifying; on the left the Hill rises almost

perpendicular, like a Wall; till being come about half Way, you have

a steep, impassable Height on the Left, and a monstrous Casm or

Ditch on your Right; deep almost, as the Monument is high, and the

Path, or Way, just broad enough for you to lead your Horse on it,

and, if his Foot slips, you have nothing to do but let go the

Bridle, least he pulls you with him, and then you will have the

Satisfaction of seeing him dash’d to Pieces, and lye at the Bottom

with his four Shoes uppermost.”

And at a much later date the genial authorof Rah and

his Friends, the late Dr. John Brown, writes of the same glen: “

There is something marvellous in the silence of these upland

solitudes; the burns slip away without noise; there are no trees,

few birds; and it so happened that day that the sheep were nibbling

elsewhere, and the shepherds all unseen. There was only £ the weird

sound of its own stillness ’ as we walked up the glen. It was

refreshing and reassuring after the din of the town, this

out-of-the-world, unchangeable place.”

And one of the doctor’s friends, inspired by the

spirit of the scene, wrote:

“Yet, I know, there lie, all lonely,

Still to feed thought’s loftiest mood,

Countless glens undesecrated,

Many an awful solitude.

“Many a burn, in unknown corries,

Down dark linns the white foam flings,

Fringed with ruddy-berried rowans,

Fed from everlasting springs.

“Still there sleep unnumbered lochans,

Craig-begirt ’mid deserts dumb,

Where no human road yet travels,

Never tourist’s foot hath come.”

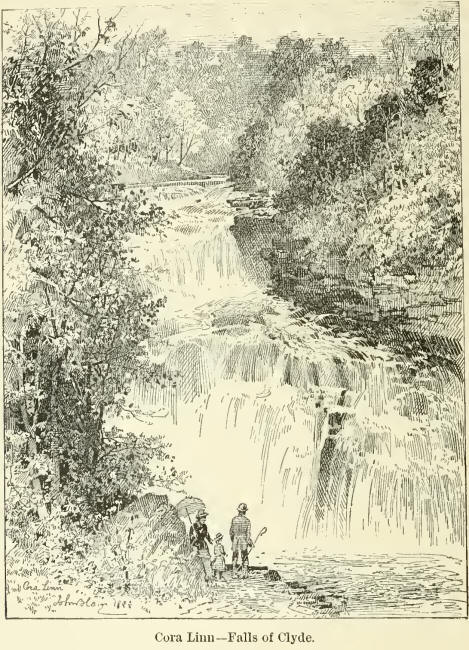

The superficial features of the valley of the Clyde

are very varied. Rising amongst the great hills of the Southern

Highlands, the course of the river lies for a time amid the moors

and rough pasture of these uplands. Lower down, and above the Falls,

it moves slowly onwards through spreading meadows, with a wide

prospect around of cultivated and wooded slopes. At Bonningtol Fall,

however, the scene changes to one of combined beauty and grandeur

not easily surpassed. The river, after taking its headlong plunge,

rushes along for a couple of miles through a deep and narrow chasm,

whose jagged rocks seem to torment and vex the once placid stream,

until, after its triple leap at Cora Linn, it escapes for a time

into the opener valley below. But along with all this impressive

grandeur we have the softening effect of the foliage from the

thousand trees and shrubs which clothe the rocky crags, and the

varied bloom of the wild flowers amongst the grassy slopes.

Here the calm beauty of the scene appears to have

affected Wordsworth, who writes:

“In Cora’s glen the calm how deep,

That trees on loftiest hill Like statues stand, or things asleep,

All motionless and still.”

And now for a few miles we see the river once more

comparatively quiet, and notice the angler wading in the shallows,

or poised on some rocky ledge, deftly throwing his deceptive fly to

catch the sportive trout. The deep and sombre ravine of Cartland

Crags is passed on the right, with its caves where Wallace found a

hiding-place, and its magnificent viaduct by Telford, with its

tapering piers and arches rising high overhead.

Once more at Stonebyres the river makes a series of

leaps through a rocky chasm, and thereafter flows onward more

leisurely through the orchard district above Hamilton. Here let us

take leave of the Falls, saying with Sir John Bo wring:

“O! I have seen the Falls of Clyde,

And never can forget them;

For Memory, in her hours of pride,

’Midst gems of thought will set them,

With every living thing allied:

I will not now regret them.”

This part of Lanarkshire appears to have been

celebrated for its orchards from an early date. Thus we find in the

Statistical Survey of Scotland:—“Orchards are of considerable

antiquity on the Clyde. Merlin the poet, who wrote about the middle

of the fifth century, celebrates Clydesdale for its fruit. The soil

and climate being inland, and consequently free from the blasting

influence of mildews and fogs, may account for its being so

favourable for the cultivation of orchards. At first they were

planted in the shape of gardens, attached to houses for the

accommodation of resident families. For two centuries or more they

have been cultivated as a source of profit; they chiefly prevail,

and are most extensive and productive, on the north bank of the

Clyde, having a southern exposure, though on the south bank there

are also a considerable number, and some of them very fruitful.”

Campbell thus records his memories of a visit to this

district:

“It was as sweet an autumn day

As ever shone on Clyde,

And Lanark’s orchards all the way

Put forth their golden pride;

Even hedges busked in bravery,

Look’d rich that sunny moi’n;

The scarlet hip and blackberry

So prank’d September’s thorn.”

The area of ground set apart for orchards in Scotland

appears to be nearly 2000 acres, of which Lanarkshire possesses

nearly one-third. The fruits cultivated in the Clyde orchards are

apples, pears, plums, strawberries, and gooseberries. Apples are not

cultivated now to the same extent as formerly, owing to the

importation of American varieties. The culture of strawberries has

very much increased of late years, arising in part from the

extensive manufacture of this and other fruits into jams and

jellies, owing to the cheap price of sugar.

Clydesdale has long been famed for its horses, many

of which are now exported to America, and fetch large prices on

account of their great strength and other valuable qualities. The

fine lorry horses in Glasgow, drawing their heavy loads, carefully

looked after and well harnessed, are a well-known sight, especially

on the carter’s holiday, or mayhap during some civic procession,

when they turn out in all the glory of their natural strength.

A writer in the Transactions of the Highland and

Agricultural Society of Scotland thus describes them; he says: “

Clydesdale horses, the best type of which are perfect models of

strength, with shapes eminently calculated for endurance and

activity, undoubtedly are, as generally admitted, the best breed for

farm work.” On the upland farms the powerful draught of the

Clydesdale soon adds furrow to furrow in the stiff soil, and at

evening we see the cheery ploughman and “the miry beasts returning

from the plough.”

The angler can find plenty of sport on the Clyde.

Among the lonely hills, on the rocks or shallows at the foot of the

Falls, further down in the Both well haughs, or again at Carmyle in

the shade of the Kenmuir woods, he will find the trout rising to his

fly. Regarding this Mr. Robert Blakey in his book on Angling says:

“The waters from El van foot to the primary rivulets of the river

are full of fine trout; and there is a splendid flyfishing range of

many miles in extent. The streams are numerous and rippling. The

trout found in these waters are of very good quality.

The Falls effectually prevent salmon ascending higher up than a few

miles below Lanark. The rod-fishing is interrupted by

the Falls, which are objects well worthy of a visit from the

tourist. Below them good fishing again commences, and continues down

to within three miles of Glasgow Bridge.

There are no tributaries of the Clyde of so much

fishing repute as to induce the tourist to turn aside from the main

stream. If he fishes it properly from its source to the confines of

Glasgow he will find the range of waters very interesting, and

capable of affording him ample sport.”

Following the course of the river we reach Hamilton,

with its ducal palace showing above the tall trees which cover the

haugh lands on the left bank, whilst indications of the utilitarian

progress of the age may be seen on the opposite side in a

briskly-going colliery placed close to the line of the old Homan

road. A fine sweep of the river with high terraced banks on the

right, on which part of the town of Bothwell is built, also suggests

a time long before our historical reckoning when a wider stream

swept past, or estuarine waves beat, on the higher slopes, which at

that time probably formed an island.

Bothwell Bridge, as originally built, appears to have

been of the style commonly adopted by the earlier bridge-builders,

that is, a high arch or arches in the centre, nearly if not

altogether semicircular, with smaller arches towards the ends or

sides of the river. The roadway was also narrow, and this, combined

with the great steepness of the gradients on each side of the

central arches, must have rendered the passage of wheeled vehicles a

laborious process. We have still a number of such old bridges

remaining in different parts of the country; some preserving the

early characteristics referred to, others showing improvements in

wider roadways and less steep gradients.

The Bridge appears to have been built at an early

date. It was originally only 20 feet wide, had a steep roadway, and

was fortified by a gateway at the Hamilton side. It appears to have

retained its smaller side arches till 1826, when it was widened; the

addition which was made on the up side was 22 feet. This difference

in the mason work is readily noticeable, as the old or downstream

part of the centre arches is of a kind of ribbed work, the new part

being plain in the soffit or under part of the arch. The piers,

which are 15 feet thick, have heavy starlings both on the up and

down side of the stream. Some years ago the width was still further

increased by iron work carrying a footway 5 feet wide. The footway

thus projects from the stonework of each side, and the carriage

roadway, which is 30 feet wide, extends over the whole breadth of

the stone structure. There are now four arches of 45 feet span, and

the length of the bridge from bank to bank is 225 feet.

The roadway of the bridge is now level, and the road

on each side rises with a considerable gradient. The old road on the

Glasgow side was much steeper than the new approach, and had in

addition the disadvantage of leaving the bridge at nearly a right

angle, turning sharply in the reverse direction as it ascended the

hill. In coming down this hill on a dark night, taking the sharp

turns required to get on the bridge, must have called for all the

well-known skill of the drivers of the mail-coaches of the old days.

Standing on the bridge and viewing the changes which have taken

place there, it is difficult to picture to one’s self the unsettled

and troublous times of our forefathers, when the struggle for its

possession took place. When

“The muskets were flashing, the blue swords were

gleaming,

The helmets were cleft, and the red blood was streaming.”

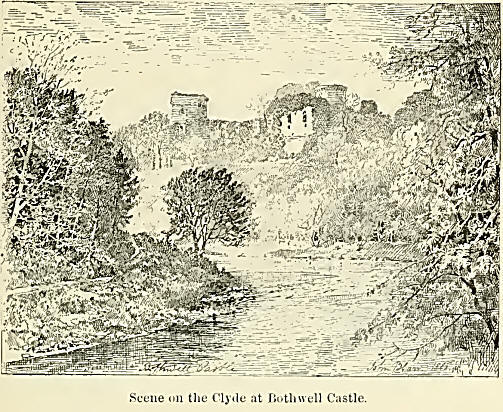

Passing the Blantyre mills, where at one time the

great African traveller Livingstone worked when a boy, and who was

born at the village of the same name adjoining, the river flows

through the steep and beautifully-wooded slopes between Blantyre

Priory and Bothwell Castle.

After passing Uddingston the course of the river is

through Kenmuir Wood and past Carmyle—favourite haunt of fisherman

and artist—and as it winds along in the flat grounds it passes in

turn some well-known landmarks, such as the Clyde Iron Works, the

site of the old Glasgow Water Works, and then through the high

arches of the old bridge leading to Eutherglen, the handsome tower

of the town building of this ancient burgh rising high on the left.

Hugh M'Donald in his interesting Rambles Round Glasgow, says: “The

steeple of a small though very ancient church, on the site of which

the present one was built, stands in the vicinity, a venerable

memorial of bygone ages, associated with recollections of several

interesting events in Scottish history. According to Blind Harry,

the biographer of Wallace, a peace was concluded here between

England and Scotland in 1297.” Sweeping in a fine curve round

Glasgow Green, and passing through the arches of the various bridges

which connect the northern and southern parts of the city, the river

holds its way to the sea, hemmed in now by quay walls and dykes,

with the buckets of the dredger constantly scooping out the loose

material from the bottom, and thus fitting it to bear on its now

broadening bosom the vast fleet of vessels, new and old, which

constantly ply on its waters.

The valley of the Clyde from Glasgow downwards is

wide and open, with great areas of comparatively fiat and fertile

land stretching hack on either side to the ranges of hills which

bound its course to north and south.

Several fine old mansion houses are still to be seen

on the banks, many of them now incorporated in the numerous

shipbuilding yards which line the river.

Campbell—with more of sympathy for nature than for

the triumphs of science and art—expresses himself forcibly on the

changes which have taken place through the shipbuilding and

engineering industries on the river banks:

“And call they this Improvement?—to have changed

My native Clyde, thy once romantic shore,

Where Nature’s face is banished and estranged,

And Heaven reflected in thy wave no more;

Whose banks, that sweeten’d May-day breath before,

Lie sere and leafless now in summer’s beam,

With sooty exhalations covered o’er;

And for the daisied greensward down thy stream

Unsightly brick-lanes smoke and Banking engines gleam.”

About 10 miles from Glasgow the hills on the north

side of the valley approach the river, and from a slight elevation

called Dalnottar Hill a magnificent view is obtained of the now

widening Clyde, with Dumbarton Rock and the distant hills above

Dunoon filling up the distance. This view has brought several

artists of high reputation to portray its features on canvas. Lovely

at all times as the view is, it is specially so on a fine summer

evening, when the sun, now nearing the western hills above the Holy

Loch, throws a long trail of luminous splendour all along the line

of the flowing stream.

Near this point the Forth and Clyde Canal joins the

river, the Roman wall terminates but a short distance below, whilst

the adjacent village of Old Kilpatrick has the special prestige of

being, according to authentic tradition, the birthplace of St.

Patrick, Ireland’s patron saint. The harbour of Bowling, where the

bulk of the river steamers quietly doze away during the winter

months after their busy summer’s work, the monument to Henry Bell,

who has the distinguished honour of having started the first

passenger steamer in European waters, the Comet, and the great

basaltic hill of Dumbuck completely fill the eye of the observer as

he contemplates the scene; whilst, turning to the southern side, he

sees the handsome mansion and grounds of Erskine House.

Onwards the river sweeps to the sea, hurrying past

the Yale of Leven, which opens out to the north, with the massive

form of Ben Lomond overlooking the surrounding hills. Wide stretches

of sandy flats now show themselves when the tide is out, but the

navigable part is kept clear by training walls and constant dredger

work, and the sea breezes now curl the waters as they flow past

Port-Glasgow and Greenock, to mingle with the salt waters of the

tidal wave which beats upon the coast.

Around us now is a varied scene: shipping, from the

full-rigged ship and the 5000-ton steamer to the 5-ton yacht and

steam-launch; towns and villages lining the shores with the villas

and mansions of the prosperous Glasgow merchant; while we may catch

a glimpse of the evening steamers racing from the nearest railway

terminus, each with its load of business men returning to their

families at the coast. The beauties of the Firth of Clyde are

deservedly well known, and for this we have to thank the

enterprising steamboat-owning firms, who have for more than half a

century been actively engaged in opening up the various now

well-known routes and consolidating their efforts in connection with

railway and coaching transit.

The Firth of Clyde just below the “ Tail of the Bank

” presents many of the well-known characteristics of the West

Highland scenery, which in turn is like a miniature Norwegian

coast-line. The arms of Loch Long, the Gareloch, and Holy Loch run

into the wild Highland hills beyond, like the fiords of the old

Norse land, whilst the Alpine peaks of Arran are seen far away over

the low and fertile hills of Bute.

“In night the fairy prospects sink

Ay here Cumray’s isles, with verdant link,

Close the fair entrance of the Clyde;

The woods of Bute no more descried,

Are gone.” |