|

Neptune's Staircase - On

Board a Trawler from Lowestoft - The Keppoch Bard - I Sail up Loch Lochy -

Sir Ewen Cameron - A Hot-tempered Chief - Tinkers de Luxe at Invergarry -

The Man who Saw a Water-Bull - Forward to Aberchalder.

HOW powerfully a good

square meal can affect a man's outlook! My feet were comfortable for the

first time in days, for I had bought a new pair of shoes at a little shop

in the main street, and made a gift to the hotel porter of the wretched

instruments of torture I had been wearing. I felt ready for anything, and

I decided to get a lift back towards Fassifern and make for Moy by the

hill-path which I had funked at half-past four the previous afternoon. I

had heard that a tradesman's van was due to go in the Fassifern direction

in about three-quarters of an hour, and I decided to beg a lift,, so I

went down to Banavie to have a look at the Caledonian Canal until the van

turned up.

I wonder if it is realised

how close the connection is between the Caledonian Canal and the Rising of

'Forty-five. It was the trustees of the Forfeited Estates who, in an

effort to improve the Highlands and give employment to the crofters, first

put forward the idea of building the Canal. They asked James Watt, the

steam-engine man, to have a look at the Great Glen and make a report. Watt

said that a canal could certainly be made, but the idea was dropped, and

thirty years passed before anything more was done. Nowadays the Canal may

be thought no great shakes as an engineering triumph, but a century ago it

was one of the wonders of the world.

Thomas Telford was the man

who built it, and if ever anyone deserved his tomb in Westminster Abbey,

it was the civil engineer who was born in a shepherd's hut on a

Dumfries-shire hillside. Apprenticed to a stone-mason, he became so deft

with the chisel that his gravestones gained him as much fame in the parish

of Westerkirk as the Scots verses he wrote under the name of Eskdale Tam.

He taught himself French, German, and Latin; and when he had saved a

little money he studied architecture in Edinburgh, and then went to London

to hunt for a job. According to the song, you can't keep a good man down :

in a short time Thomas Telford had found his feet ; and there is hardly a

county in Britain that does not to-day carry his work upon its landscape.

He was called abroad to plan the inland navigation system of Sweden, and

the Scot who began life in a shepherd's hut in Eskdale found himself with

a Swedish order of knighthood. Some say that his greatest work, greater

even than the Menai Suspension Bridge or the St. Katherine Docks at

London, is the road that runs from Inverness into Sutherland and the

North; but he will always be remembered by his countrymen as the maker of

the Caledonian Canal. If he had cared much for money, he could have built

up a vast fortune and lived like a Ruritanian prince. But for years his

only home was a room in the Old Ship Inn at London. It was there he

entertained his many friends, and in his old age they persuaded him to

move into a house of his own. He used to relate with a quiet chuckle what

happened when he informed the landlord of this decision. The inn had just

changed hands, and the new innkeeper was struck dumb with horror. "But you

can't leave, sir!" he gasped out. "Why, sir, I have just paid £750 for

you!" He explained that he had been charged this additional sum for the

inn because of the custom Telford brought to it. And I am told that in the

Great Glen some of the people still repeat the tales their grandparents

told of him how he used to sew on his own buttons, and patch his clothes,

and how he liked to walk about in the evenings among his Highland workmen,

and have a dram with them beside the fire after each day's work on the

Canal was done. The

task that faced Telford, as he cut that long channel between the North Sea

and the Atlantic, was a pretty grim one. He had to blast and dredge his

way up from Fort William at one end, and from Inverness at the other, to a

meeting-point in the Great Glen that is one hundred feet above sea-level.

He had estimated the cost at £350,000; but the war with France sent prices

soaring. When he began work, his labourers were paid eighteen pence a day,

but ten years later their wage was half-a-crown, and timber rose from

ten-pence a cubic foot to three shillings and sixpence. At one time it

looked as if the sea-lock at Inverness would beat him completely, for he

had to run it out into the open Firth for over half a mile and build an

artificial mound on a bed of mud sixty feet deep. Before the Canal was

opened it had cost nearly one million sterling more than he had

anticipated. He had hoped to finish it in seven years, but it took nearly

twenty-and another twenty after that before the final improvements were

made. It was planned to accommodate the biggest British and American

trader afloat, but times have changed, and to-day most cargo vessels must

take another route. Even the sturdy old Leith salvage-ship, Bullger, when

hurrying to a wreck on the west coast, had to go round by the Pentland

Firth, for she would have scraped her bottom plates on the sills of some

of the locks. There is, however, one class of vessel that passes through

the Canal every year-the trawlers from the east coast - and when I got

round to "Neptune's Staircase," Telford's name for the eight locks at

Banavie, I found a score of these trawlers jammed as tight as a shoal of

the herring they had been seeking in the western waters. They were

returning home to the North Sea, and I wondered how the fishing had gone.

Having twenty minutes to spare, I strolled along the lock-side and spoke

to a cherub-faced young man who was smoking his pipe beside the tiny

wheel-house of a trawler.

"Fishing?" he said. "No fish to be got. It's

been a poor year. These damned foreigners are killing the trade. Still,"

he added, " we shouldn't grouse at the foreigners. They eat about

three-quarters of the fish we catch."

"It beats me why we don't eat more herring in

Britain," I remarked.

The young man smiled, eased the red

handkerchief that was round his neck, and shrugged his shoulders. "I

haven't got much use for a herring myself," he admitted.

It certainly wasn't a Scots tongue he had in

his head; and when I asked him where he came from, he named to my surprise

an inland Essex village a few miles from where I live. Presently I

learned, again with surprise, that this young man with the cherubic

countenance was the skipper of the boat, and most of his crew were on

sharing terms with him. "Care to come below ?" he asked, knocking out the

ashes of his pipe on the low bulwarks.

I stepped aboard and picked my way among the

piles of fishing-gear. The lifeboat was warped down aft; and above the

engine-room, some washing had been hung out to dry. Ducking my head, I

entered the deck-house, in the corner of which was an open trap. Down

through this the skipper went, and I followed him on the iron ladder, to

find myself in a tiny dug-out, with a table in the middle and bunks all

around. The atmosphere was fetid with human breath and sweat.

"Tea?" said the skipper. "We're always ready

for tea on this boat."

He shouted up the ladder, and in a few minutes

two huge enamel mugs of black tea were put on the table by an

earnest-faced young man who looked more like a City clerk enjoying a rough

holiday than a cook on a trawler. Where, I wondered, were the old salts of

yesteryear-the grim old teak-faced shellbacks of square-rig days? Do all

herring fishermen look like amateur yachtsmen out for a spree ? The

skipper was intelligent, a reader of books, and we talked about Prince

Charlie. He was interested to hear about my walking-tour; and when I told

him my journey would take me up the Great Glen as far as Loch Oich, he

offered me a lift in the tone of one who invites you to share a taxi-cab.

A lift on a trawler. It sounded attractive, but I explained that it was

out of the question. I was going back towards Fassifern to walk over the

hills to Moy. There is, however, an adage about the affairs of mice and

men; and we climbed up on deck in time to see the tail end of the

tradesman's van disappearing westward.

Here was a blow. I stared after the van until

it had rounded the distant corner. I had solemnly vowed to return and walk

to Moy by the hill-path; and now it seemed that I must either trudge back

over these miles of hard highway or hang about in the hope of finding

another conveyance.

With a sudden impulse, I turned to the skipper and told him I would sail

with him up the Great Glen. As for the hill-path to Moy, all thought of it

went whistling down the wind, and the poor fragments of my broken oath

splashed overboard into sixteen feet of water. I smothered my conscience

with the thought that from Moy onwards I would be following the Prince's

tracks-not indeed upon the road, but on the sea-road that runs beside it.

The lock-gates swung slowly open, propellers thrashed the water, and the

covey of trawlers began to move.

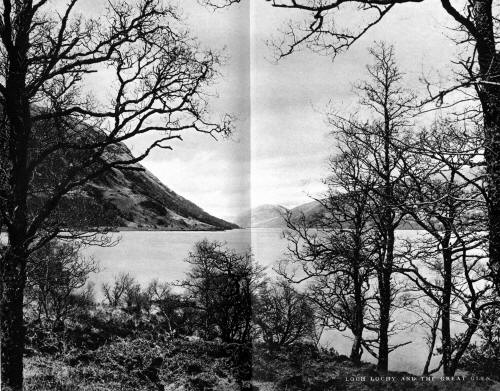

An hour later we had climbed up fifty feet

above sea level and were steaming slowly up the Canal towards Loch Lochy.

The leading boats left an enormous wash, which we picked up and sent

splashing high on the artificial banks. I noticed that several mountain

streams flowed into the Canal by sluices, while others ducked under it

through culverts and fell into the river Lochy below. I will admit that,

from the deck of the trawler, Ben Nevis was a more imposing sight than

from the road near Fort William. Perched high on the mountainside like a

raven's nest there is a little house which marks the entrance of the

tunnel through the Ben, and you can trace the pipe-lines that carry the

water from Loch Treig down to drive a team of turbines, each of which

develops nine thousand horsepower. I am told that the tunnel through Ben

Nevis is fifteen miles long, one of the largest of its kind in the world,

and before it was finished a million and a half tons of rock had been

excavated. The completion of the new Laggan scheme will mean that so much

water will be artificially carried down to the powerhouse at Fort William

that it would be enough to supply the domestic demands of half the

population of Great Britain. This will flow from the turbines into Loch

Linnhe, and one wonders what Loch Linnhe will think about it. It will

certainly provide the pleasant folk of Fort William with an alternative

topic of conversation when they are tired of telling visitors about the

prodigious height of their Ben Nevis.

Behind, we had left the ruins of Inverlochy

Castle, where lain Lom the Keppoch bard looked down upon the battle that

was fought on the plain below and made that impassioned poem, "The Battle

of Inverlochy." Although Montrose lost but one officer and three men,

Argyll's army was so smashed up that the Campbells as a fighting force

never recovered, and lain Lom revelled in the soil being fattened by the

best of the Campbell blood. But there was a much older fortress than the

present ruins at Inverlochy, and folk say that there the Auld Alliance

between Scotland and France had its beginning over a thousand years ago,

when one of the northern kings entered into a bond with Charlemagne.

Historians may scoff, but some fables take a long time to die.

We sailed on between mountains that were piled

up to the sky on either hand. To the north-east, Auchnacarry - the seat of

Cameron of Locheil - nestled somewhere among the trees ; and since the

skipper showed an eager interest in old stories about the glen, I tried to

tell him about one of the greatest Camerons of that great clan, Ewen Dubh

- the Sir Ewen of the seventeenth century. I described how little patience

he had with anyone who was less of a Spartan than himself. One night he

was storm-bound among the hills, and he ordered his followers to lie down

beside him and sleep in the snow. As he was wrapping himself in his plaid,

he saw that one of his young relatives had rolled a snow-ball to rest his

head on. Leaping to his feet, Sir Ewen kicked the snow-ball aside. "What

!" he cried, roused to fury at such degrading effeminacy. " Can't a

Cameron sleep without a pillow?"

But the yarns about Sir Ewen are innumerable.

Perhaps the best-known of all is the story of his encounter with an

English officer from Cromwell's garrison in Inverlochy Castle. The

Camerons were a thorn in the flesh of the Government troops, and in one of

the many skirmishes Sir Ewen and this officer met in a hand-to-hand

combat. The officer must have been a doughty fighter, for he managed to

parry the chief's whirling broadsword, and the pair of them finished up on

the ground locked fiercely in each other's arms. At last the Englishman

got hold of his dagger, and a moment later the fight would have ended, but

his throat was exposed, and the Cameron's teeth went into it like a

terrier snapping at a rat. Scrambling to his feet, Ewen Cameron looked

down at the crimson throat of the expiring Englishman. "God put it into my

mouth," he said; "the sweetest bite I ever had in my life!" But the story

ends far from Lochaber. After Charles II came to the throne Sir Ewen was

received at Court, and London rang with his exploits. One day he was in a

barber's shop; and the barber, noticing that his customer was from the

North, began to talk about the Highlands of Scotland. "There are savages

there, sir!" he cried, his eyes glinting with rage as he peered down into

the swarthy countenance of the man lying back in the chair. "One of them

tore out the throat of my own father with his teeth. I wish to heaven I

had that fellow's throat as near my razor as I have yours!" The Cameron

chief did not blink an eye, but he never entered that barber's shop again.

He lived until he was over ninety, and the

skipper was interested to hear of Sir Ewen's gift of second-sight. He had

it right to the end; and I told how, in the Rising of 'Fifteen, he called

out from his bed to his attendants. When they hurried in to him he

declared that his king had landed in Scotland. "Summon the household," he

ordered, "so that they may drink the health of His Majesty!" At that very

hour the exiled James was disembarking from a ship at Peterhead to join

the Earl of Mar.

It was a happy voyage I made on the Lowestoft

trawler. With the help of my map I had been able to locate Moy, a little

white-washed farmhouse up on the roadside, where the Prince stayed during

the nights of Saturday and Sunday. As we passed a tiny head land on the

south shore of the loch, I picked out Letterfinlay, once a coaching inn.

It was here that Charles, after marching from Moy, decided to spend Monday

night, for the weather was vile. But a messenger arrived to say that Sir

John Cope's army

was within sight of the Corrieyairack, and was about to march over the

mountain pass and come down to Fort Augustus. This news, which was not

accurate, inflamed the Highlanders; and in spite of the torrents of rain,

Charles decided to hurry on. By eight o'clock in the evening he had

reached the head of Loch Lochy, and there he found awaiting him four

hundred Glengarry men led by Donald Macdonell of Lochgarry. At the head of

the loch, the Prince was also joined by men from Appin under Stewart of

Ardshiel. Sending a party of scouts to keep watch on the Corrieyairack

Pass, the Prince marched on, and arrived after dark that same night at

Invergarry Castle. It

was at the head of Loch Lochy that I disembarked from the trawler. The

skipper invited me to look him up one day in the South, and to come

fishing with him in the North Sea if I felt like roughing it for a week,

but that is another story. I continued on my way, warmed by my unexpected

meeting with a man whose home was not many parishes distant from my own,

and headed for Invergarry. I was now tramping within half a mile of Ben

Tee, called Glengarry's Bowling Green, and it overlooks the flat green

strath where one of the most desperate of all clan battles was fought four

hundred years ago. John of Moidart took part in it, though Laggan-an-droma

is a far cry from the Atlantic tides that creep up round Castle Tirrim.

John was Captain of Clanranald; and Lord Lovat, who had fostered the son

of a previous chief, was determined that young Ranald Galda would become

chief in Moidart. But John was too clever to give battle, because Lovat

had Huntly's men to help him. The Frasers went home, and John followed at

a safe distance. Huntly had branched off by Glen Spean, and John of

Moidart saw his chance. On a hot July day, he swooped down on the Frasers

and their allies the Grants. After discharging their arrows, the clansmen

stripped off their plaids and rushed together clad only in their linen

shirts. And so the Battle of the Shirts was fought to an end. Lovat

himself and nearly all the Frasers were dead by nightfall, and the old

people who still talk of Blar nan Leine will tell you that only four

Frasers and ten Clanranald men survived the battle. But Providence must

have been on the side of the Beauly men, for the wives of no less than

eighty of the fallen Frasers gave birth to a man-child, each to become a

warrior in the place of his dead father.

As I looked at the streams that came splashing

down the mountainsides and flowed into the Canal, I remembered the story

about a woman who lived here in the days before the Canal was built. One

of these hillburns formed the boundary between Glengarry's land and

Locheil's, and at a point above her cottage it could easily be deflected

from its course and made to flow either into Loch Lochy or Loch Oich. When

the factor came from Glengarry to collect her rent, he found the stream

flowing down to the east, which put her outside his boundary; and when the

Cameron factor arrived, the water was tumbling down westward towards Loch

Lochy. An hour's work with a shovel now and again enabled this adroit old

body to live rent-free for years.

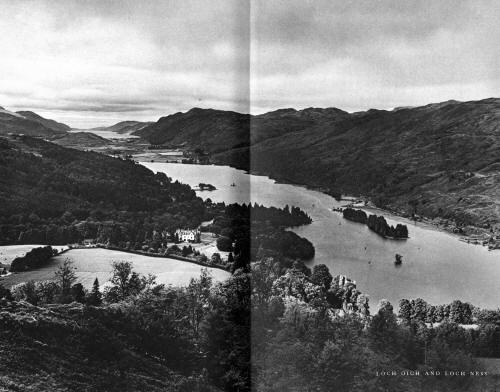

When I came to the shore of Loch Oich the

smoke of the trawlers hung like a tiny cloud in the distance. Loch Oich is

small, about four miles long, and it is one of the loveliest inland lochs

I have ever seen. The wind had fallen, and the water was like a glittering

sheet of mica between the mountains.

I found it a little difficult to adjust myself to the scenery in the Great

Glen. In the west country, among the grey jagged mountains, I had felt

almost all the time that I was alone-indescribably alone -in the heart of

a desolate and fairy-haunted land. But in the Great Glen, the high hills

are softly rounded, and there are many young plantations of trees that

keep reminding you of the handiwork of man. Compared with Moidart and

Arisaig, the Great Glen has a well-manicured look. In the West, the sight

of a cottage in a corrie had made me blink, as though it were a miraculous

thing to see there a wisp of smoke and signs of life. But here, although

few houses can be picked out on the hillsides, I did not gaze upon any of

them with surprise : it seemed natural that folk should live in this more

homely place. The oceangoing ships on the Canal, and the motor-buses that

daily race up and down the glen, remind you that you are in touch with the

world of cinemas and sixpenny-stores. As I trudged eastward, I wondered if

many people spoke Gaelic in this place. And then I was brought up short at

the sight of a long Gaelic inscription on a .damnably ugly monument by the

roadside. I found

that there was not only Gaelic carved on this thing, but French and Latin

and English as well. I hadn't read many lines of the English before I knew

that this must be the notorious "Well of the Heads." The incident of the

Seven Heads is usually referred to as a barbarous piece of Highland

cruelty which would be better forgotten. I disagree. The episode was less

barbarous than the monument, and the chief who erected it was so

ill-informed about it that he had the wrong date carved upon the wretched

obelisk. In the seventeenth century, the killing of the seven Keppoch

murderers was no more than a reasonable act of justice which the Glengarry

chief himself had refused to carry out. It was Iain Lom the poet who had

the courage to exterminate the seven rogues that had murdered the young

Keppoch chief, and the fact that the murderers were his own nephews did

not hold him back. There is at least one thundering lie in the Gaelic

inscription, which is quite different from the English, for Lord Macdonell

and Aros certainly did not order this act of vengeance ; and the severed

heads of the murderers, which were washed in the water of this well, were

in all likelihood flung at the feet of Lord Macdonell as a gesture of

contempt, since he himself had refused to make any move in the affair. It

was in fact Sir James Macdonald of Sleat who backed lain Lom, and moreover

they had the full approval of the Privy Council. But why a monument should

have been put up for what was no more than a sound bit of police work it

is hard to understand ; and we have the word of Lord Cockburn that Thomas

Telford, when he was building the Caledonian Canal, saw it soon after it

was erected and could scarcely keep his hands off it. Alexander Ranaldson

Glengarry was the man who had it built, and it is little more than a

monument to his own arrogance. Lord Cockburn, a pretty sound judge of men,

called him a paltry and odious fellow, selfish, cruel, base, dishonest,

with all the vices of the bad chieftain and none of the virtues of the

good one. Cockburn declared that Glengarry's only act of physical courage

was one which he and Telford watched by the side of the loch, and the

chief was driven to it by his own insolent fury. He wanted to cross the

loch in a boat which had already put out from the shore. He shouted

angrily to the men at the oars, but their only reply was a laugh. With a

howl of rage, Glengarry spurred his pony into the water to swim after the

boat. Telford remarked to the group beside him that he hoped Glengarry

would drown, and the place would be well rid of him. But the sturdy pony

carried him more than half-way across the loch, and at last the dripping

figure clambered into the boat.

The truth probably is that Glengarry had shown

his truculent side to Lord Cockburn and Telford, as he did to all

strangers who failed to kow-tow to him. The poet Southey went with Telford

when he paid his duty-call on the chief, and they were received with great

civility, but Thomas Telford was too blunt a man for Glengarry's liking.

And Sir Walter Scott, an even better judge of men than Lord Cockburn, said

that Glengarry was warm-hearted, 'generous, friendly, full of information

about his own clan and the customs of the Highlanders. So we can take our

choice. Glengarry may

have been a popinjay, but he was no poltroon. Charmed with the bright eyes

of Miss Forbes of Culloden at a dance in Inverness, he pressed his

attentions upon her, and a young Black Watch officer protested. Afterwards

in the mess, Glengarry slashed him across the face with his cane. The

officer, a grandson of Flora Macdonald, challenged him to a duel. On a

sunny afternoon they met with loaded pistols on the links near Fort

George, and Glengarry wounded his man, who died a month later. When he was

charged with murder, his first impulse was to show a clean pair of heels ;

but Henry Erskine who had been briefed for the defence urged him to stand

his trial. Never did anyone have a closer shave, and it was Erskine's

eloquence that got him acquitted. But this did not tame him. He was seldom

out of the Law Courts over petty rows with his tenants, and he almost

always lost his case. It was his custom to strut about with an entourage

like the "tail" of a Highland chief of an earlier age, and he claimed to

be the hereditary chief of all the Clan Donald. Some years before his

death he had a public row with Clanranald; and I have in front of me as I

write, a pamphlet of over a hundred pages of vitriolic argument entitled

Vindication of the Clanronald of Glengarry which he published in

1821. In this he said he found it incumbent upon him to make a "public

disclosure of the bastardy of John MacAlister of Castel-Tirrim." This was

the famous John of Moidart, and Glengarry declared that John and all the

succeeding captains of Clanranald were usurpers. The feud, if it can be

called a feud, lasted until 1911, when a treaty was drawn up between the

present descendants of Glengarry, Clanranald, and Macdonald of Sleat. It

is an astonishing document. It mentions the great jealousy and dissension

among the different branches of Clan Donald in the past and the consequent

" great injury and prejudice suffered by our whole race and kin." In this

treaty, none of them abandons his claim to the supreme chiefship of Clan

Donald, but each agrees that when more than one of them are present on any

occasion when the question of precedency arises, they will draw lots to

decide who will have the preeminence for the time being. One might be

pardoned for wishing to be present when these modern descendants of dead

chiefs spin a coin to decide which will walk in first to dinner ! And,

finally, they agree that Macdonald of Sleat shall be permitted by custom

to use the designation "of the Isles." And so ends an old and trumpery

family squabble. When this document was signed and sealed in 1911 by the

three Macdonalds, at Bridlington, at Bordeaux, and at Tuapse in South

Russia, Alexander Ranaldson Macdonell of Glengarry must have turned in his

grave with a groan of despair.

In the pine-woods I stopped a cyclist to ask

him where Invergarry Castle was to be found, and he pointed to lodge gates

along the road. At the lodge I was given permission to enter the private

grounds of the present Invergarry House, and made my way down to the

ruined castle at the lochside.

It was here that the Prince arrived in the

darkness of that stormy Monday night in August after a march of about

fifteen miles from Moy. But it was not the chief who welcomed him ; for

John Macdonell of Glengarry was a weak drunken fellow, and he was skulking

in Perthshire. He had indeed visited Sir John Cope in his camp at Crieff

on the previous Wednesday and assured him of his loyalty to the

Government. He was playing a double game. If the Rising failed, he was

ready to swear that the clan had come "out" against his wishes; if it were

successful, he was prepared to skip nimbly forward and make his obeisance

to Charles. His ruse was plain to everyone in the Prince's army, and they

were all glad he was well out of the way. With such a chief, it is not

surprising to learn that a good many of his clansmen hung back and had to

be forced out by threats. Lochgarry issued the orders. Before the Rising

he had been commissioned as an officer in King George's army; although he

had his doubts about the wisdom of the Prince's enterprise, he tore up his

commission and joined the Jacobite force ; and with Glengarry's second son

Angus, who had been on a visit in Rannoch while the clan had gathered, he

entertained the Prince on that tempestuous night at Invergarry Castle.

But long before the days of the 'Forty-five

the old glory of this fortress had departed. Built upon the Rock of the

Raven (the war-cry of the clan), it was gutted under General Monk when he

made his victorious march against the loyal clans in June 1654. The

Glengarry of that time rebuilt it-he was the great Alastair Dubh who had

led the attack under Claverhouse at Killiecrankie - and he narrowly

escaped the same fate as the Macdonalds of Glencoe. Indeed, the infamous

Stair wrote to General Livingstone a month before the Glencoe massacre:

"These troops posted at Inverness and Inverlochie will be ordered to take

in the house of Invergarie and to destroy entirely the country of Lochaber,

Locheil's lands, Keppoch's, Giengarie's, and Glencoe . . . and I hope the

soldiers will not trouble the Government with prisoners." But Glengarry

had signed the oath of allegiance within the allotted time, and his people

were spared. His castle, however, was used for many years as barracks for

a Government garrison: a bitter pill for Alastair Dubh. After the Rising

of 'Fifteen, it was burned again ; and finally it was roofed over to

become the lodging of the manager of some iron-works that the York

Buildings Company had set up in the glen. Thomas Rawlinson was his name,

and some say it was he who invented the philabeg or little kilt, because

the long plaid impeded the Highlanders he employed, and he was shocked to

find them at their work indecently naked. But whether or not it was this

Rawlinson who was the only begetter of the modern kilt-and his claim to

this fame is doubtful-the fact that he took up his lodging in the old

castle was resented by the Glengarry men. He invited some of them to

dinner one evening, and after the usual toasts had been drunk Rawlinson

rose to his feet and said in a grandiloquent voice, "Be welcome to

anything in my house." At this an old clansman jumped to his feet, and

cried, "Damn you, sir; I thought it was Glengarry's house!" They knocked

out the candles and made a rush for the man at the head of the table. It

was fortunate for Rawlinson that he managed to escape in the darkness, and

later on the old place came back into the hands of its rightful owners.

On that Monday night in August 1745, when the

Prince arrived at Invergarry, the scene in the castle was perhaps the most

romantic in all its history.

Until a late hour, Charles discussed with the

chiefs his immediate plan of campaign. King George's army under Cope had

arrived at Dalwhinnie, about a day's march south of the Corrieyairack, and

the Prince had a pretty fair idea how weak that army was. Cope had marched

north from Stirling, with a great rattle of drums, but what was his next

move to be? If he tried to make a forced march over the Corrieyairack

Pass, the Prince's scouts who lay up in the mountains would have the word

down to Invergarry within a few hours, for they were local men and knew

every corrie and sheep-path in the darkest night. The discussion in the

castle was interrupted by the unexpected arrival of Thomas Fraser of

Gortuleg. He said he had come with a message from Lord Lovat, and Locheil

presented him to the Prince. He spoke of his own loyalty and Lovat's, but

he was there to play Lovat's dangerous game of keeping a foot in both

camps. He told the Prince how Duncan Forbes of Culloden, although a sick

man, had posted north to keep some of the most powerful clans in the

Highlands from joining in the enterprise; and he said that Lovat wanted

the Prince's warrant to take Forbes alive or dead-a difficult task,

because the Lord President had a hundred armed men in his house, with

artillery mounted outside. But the suggestion of a raid on Culloden House

was at that time mere bluff, for Lovat was almost daily sending fervent

letters of friendship to Duncan Forbes.

Fraser of Gortuleg then asked for the

commission of Lord Lieutenant and Lieutenant-General for Lord Lovat which

James had signed two years before. These documents were in the baggage

that had not yet come on from Moy, where the Prince had slept the previous

night. Not that this mattered a whit ; the request for them was but

another part of Lovat's bluff; for if the Rising succeeded, and James came

to the throne, it was a dukedom that Lovat was after, and he knew that the

patent was already signed and sealed.

Gortuleg went on to explain why Lord Lovat had

not called out his clan: Forbes of Culloden had his eye upon him, and the

garrison at Inverness and Fort Augustus were ready to come down on him if

he made the slightest move-in fact, to the old man's sorrow, his loyal

hands were tied. The

oily-tongued Fraser of Gortuleg then slipped away home to Loch More, a few

miles east of Foyers, to sit down and write to Forbes of Culloden, giving

all the information he could about the Highland army. He had not only lied

to the Prince, but had been a spy in his camp.

But something else happened on that Monday

night at Invergarry Castle. John Murray of Broughton came strongly into

the limelight. Two days before at Moy, he had been appointed secretary to

the Prince, but previous to his appointment he had drawn up a bond of

loyalty for the chiefs to sign. This he now produced, and they all put

their hands to it, each pledging himself that he would not make a separate

peace without the consent of the others. If ever a document was

unnecessary, it was surely the one which the over-shrewd Murray of

Broughton folded away so carefully ; and there is a grim irony in the fact

that the only man in the castle that night who turned traitor was the one

who had written out the bond.

I stood within the broken walls of the castle. Some of the stones are

still black from the gunpowder and flames that finally put an end to the

place after Culloden. Ivy is climbing skyward, smothering the place in a

green pall, and a rowan tree has taken root high in the walls where the

Prince had so poor a shelter in the lodging of the departed Rawlinson.

The decay of a noble building damps the spirits, and I was glad to get

away from Invergarry Castle. Set on its Rock of the Raven, this castle

must have been a fine sight when Alastair Dubh gathered below the walls

the flower of his clan and marched them off to join Claverhouse and play

their gallant part at Killiecrankie. But I would rather have seen it -

half-ruined as it then was-on the bleak dawn of Tuesday, 27th August 1745,

when more than seventeen hundred Highlanders rose from the wet grass where

they had slept, and unwrapped their plaids from about them, while the

Prince looked down upon them from a high window, with eyes that were

'still heavy with sleep.

I climbed up the hill into the tiny hamlet of Invergarry. A hotel, a few

cottages, and a church are strung out on the roadside above the burn that

flows down from Loch Garry among the hills. It is a pleasant place, with a

Macdonald here and there, but few of the old clan are now living on these

hillsides. I found a lodging in one of the cottages, and after tea I

sauntered down to the hotel to sample the whiskey. At the door, I fell

into talk with a man in brown knickerbockers. We exchanged a pipeful of

tobacco and sat in the porch. In the course of our talk he learned about

my intention to walk to Edinburgh, and when I explained that I was on a

Jacobite pilgrimage, we began to talk about the 'Forty-five. He refused to

hear a good word about the Prince. A poor fish, he called him, and a

damnable Papist. I tried to point out that, although Charles was a

Catholic, the first church service he attended in Scotland was conducted

by an Episcopalian clergyman, which at least showed his toleration in

religious matters. Then the man in the knickerbockers went on to say that

the Prince brought nothing but bloodshed and oppression to the Highlands.

I admitted the bloodshed and the oppression, but suggested another point

of view-that the 'Forty-five was a pouring out of the spirit of loyalty to

one whom many Highlanders regarded as their king by divine right. I also

suggested-or rather I flatly declared-that Prince Charles was a better man

than George II, and would have made a better king, but the reply was an

explosive "Bah!" The Prince came to Scotland with a few Irish scallywags,

he retorted: since he was such a fine fellow, why did he not find better

men than these to bring with him?

I pointed out that the story about his

companions being mere Irish adventurers was picturesque but untrue.

Granted, he would probably have been better without Sir John Macdonald,

who was fond of the brandy bottle and had a vile temper, and granted also

that the exiled James took a strong dislike to Colonel Strickland, who

fell ill and died at Carlisle; but the worst of the lot was not a

foreigner at all -he was a man born in Moidart. There to this day they

will tell you that Aeneas Macdonald, the Paris banker, got cold feet after

the landing, and skulked around the cottages persuading the Clanranald men

to stay at home. He admitted as much, and a good deal more, after he gave

himself up to the Government : indeed, he declared that he had been on the

point of coming to Scotland on private business when the Prince offered

him a free berth on board the Du Teillay, and he accepted out of

curiosity. Perhaps it was his curiosity afterwards in the French

Revolution that lost him his head in the guillotine, but it was no great

loss, anyhow. . . . As for the other men who came on the Du Teillay, they

were pretty good fellows, and there can be no doubt about their loyalty to

the Prince. "But what

about the Prince's loyalty to the clansmen who followed him?" demanded my

companion.

"Before he came to Scotland, it's said, he enrolled as an officer in the

Spanish army. If he'd been captured, he could have claimed to be treated

as a prisoner of war. But the men under him were bound to be treated as

rebels, and sent to the gallows-as many of them were."

"Whig historians are fond of raking up that

yarn," I replied. "If the Prince enrolled in the Spanish army, it was to

try to put his father's mind at rest. The Pope certainly never believed it

could save him. In coming to Scotland, he was risking his neck, and he

knew it." In his later life, I admitted, he slid downhill from one

disappointment to another. He sometimes lacked money to pay for his food

and lodging, but in his wanderings on the Continent he carried a little

purse of gold that even hunger did not force him to spend: this was to

take him back to Scotland in case the call for his return should come.

But my arguments were lost upon the man in the

brown knickerbockers, and I was rather thankful when by a happy accident

the subject was changed. He jumped to his feet and pointed at a battered

motor-car that was chugging up the hill from the bridge.

"Heavens, man, look at these tinkers!"

And tinkers they were. Tinkers, not straggling

along the road behind a dirty tilt-cart, but packed into a Morris Cowley

that had been shining with new green paint around about the year 1920: a

Morris Cowley that had a regular haystack of gear piled up in the back,

with a two-wheeled trailer bumping behind. And with the passing of it, a

romantic picture went up in smoke, and I foresaw that the old-fashioned

tinker who goes shuffling along with his shaggy pony and even more shaggy

family may soon be gone from the roads of Scotland, and in his place we

will see a brown-faced plutocrat in his motor-car.

A plutocrat the gentleman in the driving-seat

certainly was. His filthy hands gripped the wheel in a manner that was

regal, his elbows jutted out importantly, and his head was cocked back as

he peered through the splintered windscreen. He had a yellow moustache

which curled so hugely round, his jaws that it might have concealed

mutton-chop whiskers below its tea-stained trusses. His bowler hat was

dented and green with age, but the brim had the same august curl as his

moustache, and perhaps one day it had adorned the head of some douce elder

of the Presbyterian kirk. His bedraggled squaw, with gold ear-rings and

spotted neckerchief, sat beside him clutching two children to her bosom.

Packed among the luggage behind was a black-eyed young man with a loudly

checked cap, the snout of which was almost adrift from its moorings, and

on his chin was the dark incipient moss of a beard which was difficult to

distinguish from the grime on the rest of his face. Beside him was a third

youngster with the glittering eyes arid the wise brooding expression of an

elderly chimpanzee: I could not make out whether it was a boy or a girl.

The ragged cavalcade rumbled past, the burst silencer of the car sounding

like a long roll of kettle-drums. Tinkers de luxe ! - bound for

some favourite eyrie in the West. We watched them until they were out of

sight, and then we ordered another whiskey-and-soda and drank to their

fortune. They deserved it, these modernists, who believed in keeping pace

with the times: and perhaps, as they asked for pots to mend and tried to

sell clothes-pegs to reluctant housewives, their mendicant whine was

already giving place to a blustering bravado which fitted their rise in

the social scale.

After we had finished our drink, the man in the brown knickerbockers asked

me to dine with him. I refused, and then compromised by saying that I

would have dinner at the hotel, and we could feed together. I had made- no

arrangements at my lodging for an evening meal, and I was glad of his

company. But I was more pleased still when he rose at the end of an

excellent dinner and invited me to join him on a visit to an acquaintance

of his who lived in a cottage up the road.

"The Sennachie, I call him," he said. "The

most interesting old boy in Invergarry."

We stumbled up a lane in the darkness. At the back of a row of houses, my

companion knocked on a door. I could hear the whimper of dance-band music

from a wireless loud-speaker inside. It was shut off, and presently the

door opened.

Silhouetted against the light in the room beyond stood the man who had

been described to me as the most interesting old boy in Invergarry. He

blinked at us for' a moment, recognised my friend, and upraised his hands

in welcome. "Come

away in with you." He

was a little old man, with dark brown eyes, and his black hair and pointed

beard had a touch of white. He was very broad in the shoulder, and he

walked across the flagged floor of his kitchen with an odd rolling

dignity. He looked up at us in the lamplight, his head tilted back, his

cheeks wrinkled in a smile. "And I am very pleased to see you," he said in

his soft old deliberate voice, and pulled forward chairs for us beside the

fire. "I was listening to the wireless, but it is not very good to-night.

I would rather be listening to your stories."

"We've come to hear some of yours," said the

man in the knickerbockers. "I was telling my friend here I call you the

Sennachie." "The

Sennachie !" The old man put back his head, in the sudden way he had, and

laughed again. "Ho-ho, that is good-the Sennachie ! Well, sit down, and I

will get a little drop of something in a bottle, and we will drink a toast

together." I was fascinated by his voice : it was so quiet and precise. He

spread a white napkin on a chair and brought out three wine-glasses. And

then he very carefully carried a black bottle from a cupboard. He

evidently believed in taking whiskey neat, for he filled the glasses to

the lip ; and then when we were served he raised his own and wished us

good health. "Yes, it is a good dram," he admitted, when I complimented

him on the quality of the liquor. "You will not get a bad dram in

Invergarry." I

remarked that Invergarry struck me as a pretty good place to live in.

Our host nodded. "It is a good place for an

old man to end his days. But it was a better place, I'm thinking, before

all the Macdonells went across the sea . . . All of them ? Ah, yes, nearly

all of them. There is more Gaelic spoken in Glengarry in Canada than you

can hear in this glen to-night." He shook his head. " The old sentiment

has passed away. Once a month we have our ceilidh here-it is good, very

good, but it is not like the old ceilidh when friends are around the fire

talking and singing together."

The man across the hearth asked whether it was

for sheep or deer that the Macdonells were turned out of their homes.

"It was the sheep - the big sheep from the

south country. The Highlandmen called them the 'small cattle.'" The old

man paused to take another sip from his glass, and then lay back in his

chair, the tips of his fingers together. "But there was a great man in

Glengarry at that time, a fine man. He was a Catholic priest. Father

Macdonell was his name. When the people were turned out of their crofts,

it was Father Macdonell who got them work. The only work he could find was

in the Glasgow factories. And he went there to live with them. But soon

the work stopped, and the poor people from Glengarry had not a crust to

eat. It was Father Macdonell who helped them again. He got a regiment

raised-the Glengarry Fencibles - and himself joined as chaplain. But soon

the Fencibles were done away with, and it was sad days once more for the

Glengarry men. Father Macdonell saw there was only one thing to do now. If

there was no living for them in this country, there was a living across

the sea. He took the people to Canada, and he called the district

Glengarry to keep them in mind of their old home, and it is full of

Macdonells to this day."

He replenished our glasses, and flung some

more logs on the fire. We talked of many things, and the old man's

knowledge of the world was astonishing. He lived alone ; he fended for

himself ; and when my friend with the brown knickerbockers called him the

happiest man in the Highlands he chided him gently: "In all Scotland!" he

said, with a laugh. "And why not? I have everything I need-even a friend

who can talk the Gaelic."

I told him some of the old stories I had heard

in Moidart, and he was able to correct me on more than one point of

history ; then, as was almost inevitable, we strayed towards the subject

of second-sight. "Ah,

there are more wonderful things in the Highlands than some folk are

believing to-day," he said slowly. "They laugh at us for our superstition,

as they are calling it. But I'm thinking they are beginning to take notice

of us. They have written in the newspapers about great monsters in the

Highland lochs. Monsters!" He chuckled and shook his head. "There may be

great monsters in the lochs, I do not know, I have not seen one. But I

know there are kelpies in some of them."

"You believe in the

water-kelpie?" asked the man in the knickerbockers, lighting his pipe with

a pine- splinter.

"Why not? There are surely water-bulls and water-horses in, some of the

lochs. Each uisge and tarbh uisge, we call them. When I was a young man a

laird in Wester Ross tried to drain one of his lochs to kill a water-cow

that lived in it. They worked for more than a year, but they could not

empty the loch, so they put tons of lime into the water to poison the poor

animal. But it did not die, for it was seen after that. Ah, yes, there are

water-cows and water-bulls in some of the lochs and tams."

"But why are you so certain ?" I asked.

He sat upright in his chair, and looked me

straight in the eye. "Because I have seen one myself."

"You have seen one?" I repeated, wondering if

he was trying to pull my leg.

He gave a slow nod. "I have seen a water-bull.

It was beside a tarn in Glen Barrisdale. It was, a beautiful summer day,

and the bull had come out of the water, and was standing near some cows.

No, they were not afraid of him. He was a gentle-looking creature. I went

closer so that I could see him plainly. Ah, he was a lovely animal. His

skin was dark and smooth and shining, and he had big soft eyes. He had two

black horns, turned inward. Black and bright they were, and his hoofs were

smooth and black too. He was the loveliest animal I have ever seen. So

strange and gentle-looking, with his wet skin and big eyes, big as the

palm of my hand . . . No, I made no mistake," he went on deliberately. "I

was too close to him for that. He was like no other creature I have ever

seen. I watched him for a long time, and then I had to go on my way, for I

had to meet a friend. I went back to the same place in the evening, but by

that time the animal had gone down into the tam where he lived."

The quiet tones of the old man's voice, and

the gleam of his brown eyes, filled my last thoughts as I lay that night

between cool sheets in my tiny bedroom. There are more wonderful things in

the Highlands than some folk are believing to-day ! For a little while I

listened to the hum of the Garry river in the glen below, and then blew

out the candle. I was asleep before the smell of the extinguished wick had

quite faded in the darkness.

I loafed next day. I loafed in the manner of

one who has all eternity in front of him. The sun was blazing, and I

passed the golden hours by the lochside staring lazily at the summit of

Carn Dearg and at Craig nan Gobhar, from the top of which they say you can

catch a glimpse of both the North Sea and the Atlantic.

It was after lunch before I buckled on my pack

and set out down the hill for the Bridge of Oich. There are two bridges

now, one over the river and another spanning the Canal; but the Prince's

army forded the Oich at the shallows, and then crossed the road that Wade

had built thirteen years previously. The clansmen were in high fettle.

Within twenty-four hours they hoped to confront Cope's men and to show

them the deadly force of a Highland charge. But the Prince decided to halt

for the night at Aberchalder, on the hillside, so that two or three small

parties, already on their way, would have time to join him. He slept in a

farmhouse that no longer exists, and was moving about by the peep of day.

He called for his Highland clothes, and as he fastened the latchets of his

shoes he was heard to declare that he would be up with Mr. Cope before

they were unloosed. Officers and men, to quote from the letter Fraser of

Gortuleg wrote to the Lord President, were "in top spirits and make sure

of Victory in case they meet." By nine o'clock in the morning they were up

in the Corrieyairack.

There was one thing I was quite determined

upon : I was not going to be caught in my predicament of the evening

before. It would have been utter folly to try to cross the Corrieyairack

starting so late in the day. To reach Laggan in the Spey valley before

dark, it would be necessary to breakfast early and lose no time in setting

out. So I decided to halt for the night on this side of the Corrieyairack

Pass ; and if I failed to find a lodging in a house I saw above the

bridge, I knew I could easily make tracks for Fort Augustus, which was

less than five miles up the Great Glen.

The house was empty; at least, no one answered

my repeated knocks; and I descended to the road and headed for the Fort-or

Kilcumein, as the old village at the head of Loch Ness was once called. I

was exhilarated by the thought that I was now tramping along "Montrose's

mile," for it was here his little army had encamped on the night before it

made one of the most astonishing marches in military history. Everybody

was dog tired and in low spirits. Seaforth with five thousand men lay at

Inverness, when lain Lom, the Keppoch bard, burst into Montrose's camp

with the news that three thousand Campbells and Lowlanders had reached

Inverlochy: thus both ends of the Great Glen were blocked. It was then

Montrose made his great decision. He roused his followers and they plunged

up into the snows among the hills. The men were cold and hungry, oatmeal

and water was their only food and drink, but all day they struggled along

behind their indomitable leader. Up Glen Tarff they went, crossed the

river Turret which was choked with snow, and plunged down through the

snowdrifts in Glen Roy, to reach the hillside above Inverlochy in the

chilly dusk of a February evening. When Argyll was told that the enemy was

approaching, he refused to believe it: Montrose was known to have been at

Kilcumein the night before; only a magician could have wafted them to

Inverlochy; these fellows on the hillside must surely be a few raiders

from Keppoch! . . . All night Montrose's men lay up there on the hillside,

they lit no fire, they had no food, and at dawn the tired and hungry

little army joined battle with a force of twice their number and smashed

the Campbells to pieces. Such was the Battle of Inverlochy. And it was at

some spot in this green strath where I was now tramping that Montrose,

caught as it were between the jaws of nut-crackers, decided to attempt the

impossible. If a Montrose had been by the side of Prince Charles, a

Stewart king would almost certainly have been upon the throne of Britain

by December 1745. I

reached the outskirts of Fort Augustus as five o'clock chimed out from the

tower of the Benedictine monastery. |