|

As the County of Kinross,

one of the smallest in area of the divisions of Scotland, contains within

its limited space variety of scenery and wealth of historic association

unequalled by larger counties, so Bute, one of the least considerable of

the islands of the west, appears to the intelligent observer as a miracle

of loveliness, teeming with facts and fancies of olden times. The River

Clyde, which here debouches into the Atlantic Ocean, surrounds the islands

of Bute, Arran, and the Cumbraes, each presenting a different type of

beauty from the others, and claiming diverse meads of praise. The scenery

of Arran, whose bold outline of rugged alpine peaks in barren grandeur is

thrown against the sky, contrasts with the commonplace elevation of the

Cumbraes, whose gentle, undulating eminences are too fruitful and

well-cultivated to become the home of romance. To Bute is reserved that

combination of wild, unsophisticated nature and extreme civilization which

holds the greatest charm for the tourist of modern times. From the

inconsiderable heights which this island affords, you may overlook the

broad expanse of water which lies betwixt Bute and the Ayrshire coast,

whose continuous outline becomes reduced shorewards, until it terminates

in the distant point of Port Crawford; or, looking northward, the grim

desolation of the Cowal shore presents a different scene. There the

o’ertopping Argyll mountains fade away into obscurity, filling in the

distant background with some far-remote Ben, which none save an expert

will venture to name. There are not many places in Scotland where, at one

moment, we may find ourselves—

"Far ‘lone amang the Hieland

hills

‘Mid Nature’s wildest grandeur;"

and at the next may turn to view—

"The cloud-capped towers,

the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples"

of a very advanced

civilization. Yet these are points in the

island of Bute from which the beholder may elect either to feast his eyes

upon—

"The hills embrowned with

bracken? rusty gold,

And the bell-heather,"

telling of the scanty

pasturage and waste lands which produce the men of war; or to turn his

gaze upon the—

"Deep waving fields and

pastures green,

With gentle slopes and groves

between,"

of a highly-civilized

land,

which exhibits the blessings of peace.

From a slight elevation the

eye may at one glance see the ancient town of Rothesay, stretching around

the shore of its crescent-shaped bay, and uplifting its multi-form spires

and towers above the din and tumult of constant traffic; and at the same

time it may rest upon the placid waters of Loch Ascog or Loch Fad,

embosomed amid the uplands of the island, and reposing as tranquilly as

though they were situated in the least-frequented hills of the Northern

Highlands.

The summit of the

heath-clad steep of Barone Hill permits a very wide expanse of country to

be seen; and topographers of an arithmetical turn may reckon up twelve

counties as being thus brought within the range of vision. The receding

coast of Ayrshire allows a broad sheet of water to extend southwards to

the horizon; and the Argyll shore, suddenly trending westward, and

terminating in the elongated peninsula of Cantyre, leaves Bute standing

alone amid the surrounding element—

"A priceless gem, set

in a silver sea."

The very minuteness of the

separate portions of the scene gives a kind of fairy charm to it. For it

seems as if one were looking upon some exquisite model of Scottish

landscape, wherein might be seen, upon a reduced scale, the loch, the

hillside, and the river, with every distinctive characteristic which

belongs to "the land of the mountain and the flood." And so this lovely

islet is but a microcosrn, a toy-model of Scottish scenery. One is not

astonished, therefore, to find that Bute has some pre-historic ruins of a

religious establishment, whose unwritten story must be of a remote date.

The remains of the ancient

Chapel of St Blane may still be seen nestling in a sequestered dell in the

southern part of the island; and here, if tradition may be believed, the

holy Blane has peacefully reposed for these last thirteen centuries. The

architecture of the Chapel certainly belongs to an era of comparative

antiquity, though the dates of some of the earlier chroniclers of the

Saints are no more reliable than the chronology of the Chinese historians.

The story of Saint Blane as now preserved in the traditions of the island

must be taken with "a pinch of salt," as the Romans used to say. A certain

bishop from Ireland (these Irish people early found the way to Caledonia),

called St Chattan, had selected this part of Bute as his residence, and

here he settled with his sister Erca, resolved to effect the conversion of

the pagans of Scotland to the true and universal faith. Whatever effect

the ministrations of the holy man may have had upon the natives is now

unknown; but it is recorded that whilst he was powerless to win over the

King of Scots to his religion, the beauty of his sister enticed that

sovereign from the path of rectitude. The unhappy Erca, when her crime

could no longer be hid, was visited with the punishment then deemed the

best corrective for errors of judgment. She was placed in a coracle, or

boat of skins, and set adrift upon the bosom of the Clyde, a living Elaine

in search of her faithless Lancelot. The wind and the tide bore her far

away southwards, and cast her, with her helpless babe, upon the hospitable

shore of Ireland.

Here she was rescued by two

generous Hiberthan monks, who baptized the little stranger by the name of

"Blaan," and tended and cared for him for some time. At length he was sent

to his uncle, Chattan, in Bute, who adopted and educated him for the

priesthood, and shortly after his ordination he journeyed to Rome, and was

consecrated Bishop by the occupant of St Peter’s Chair. Returning to

Scotland he settled in Perthshire, founding the sacred house of Dunblane,

of which See he was the first bishop; and after his demise his remains

were conveyed to Kilchattan Bay, in Bute, the scene of his early life, to

rest near the relics of his uncle and

benefactor.

Not far from St Blane’s

Chapel there stands a vitrified Roman fort, showing that these ubiquitous

conquerors had penetrated even here, and left the traces of their

civilizing influences behind them. Indeed, the name "Bute" is said by some

philologists to be a corruption of the Latin "buda," the name applied by

the Roman historians to the western isles of Scotland. The defective

geography of the time probably led them to imagine that the whole of the

west coast was protected by a continuous chain of islands, extending from

Orkney ("Ultima Thule") to Arran, inhabited by a savage and irreclaimable

people, upon whom the arts of Italy could exercise no humanizing power.

Bute, therefore, seems to have been the spot chosen by them as the extreme

limit of the civilization of western Scotland, and here they terminated

their line of defence.

All theories upon the

origin of the fort of Dunna-Goil, regarding which no authentic records

exist, are but founded upon conjecture, and set solely upon circumstantial

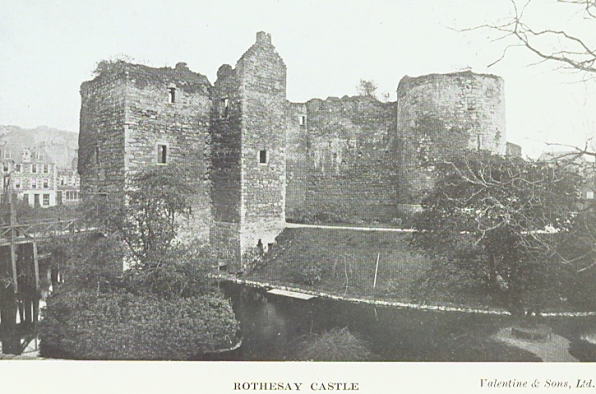

evidence. The antiquity of Rothesay Castle, though wrapt in some

obscurity, is not so far removed from written history; and as the interest

attached to it arises from its connection with known events in the annals

of Scotland, the influence of inventive romance is not so apparent.

The ancient Castle of

Rothesay is peculiarly situated. The bay takes a gigantic sweep inland

from the point of Bogany to that of Ardbeg; and at the very centre of this

hemisphere, only a few yards from the shore, this venerable pile has been

erected. Unlike most of the ancient Castles, it is built upon low ground,

and might be easily commanded from the heights. Its position, however, has

doubtless been chosen as affording an extensive view of the Firth of

Clyde, though the clustering dwellings which now surround it effectually

interrupt the prospect. The building is considerable in extent, though the

various styles of architecture and the methods of masonry employed show

that the original structure has been very much enlarged. Possibly the

nucleus around which these additions have been made was the circular tower

on the east side, which bears the greatest resemblance to the antique

forts of remote times. And the derivation of the name of Rothesay, which

authorities say is compounded from the Gaelic Roth, a circle, and

Suidh a seat, give some countenance to the theory that the circular

donjon was the earliest part of the building. The crow-stepped Flemish

gables and circle-top windows of other portions belong to a period much

nearer our own time.

The Castle has been of

sufficient compass to contain within its walls an extensive courtyard and

a private chapel. Though now entirely roofless, there are many traces left

of foundations and razed walls which sufficiently indicate the importance

and extent of the Castle. In many parts of the buildings the walls are

over seven feet in thickness, and are composed mostly of square-hewn

stones with rough rubble-work. The edifice is surrounded by a moat fifteen

feet deep by about nine feet wide, which is supplied with water from Loch

Fad, though probably in the earlier days of the Castle the waters of the

bay have laved its walls.

The main doorway is the

least imposing portion of the structure, though the sculptured arms above

it, and the portcullis groove in the lintels still challenge the attention

of the antiquary. The clustering ivy which luxuriates in every portion of

the Castle, clothing its rugged front with vesture of perennial green,

serves to enhance the romantic effect of the whole scene, and to awaken

those memories of the past which are ever associated with this "dainty

plant that creepeth o’er ruins old." And the past of Rothesay Castle is

not uneventful.

It is supposed that the

original building was erected by Magnus Barefoot, King of Norway, some

time about the end of the 11th century. This redoubtable sea-king had

conquered the Hebridean Isles, and, descending as far south as Bute, he

there established a post from which he might menace the mainland of

Scotland. And if this tradition be correct, it is curious to note that

this Royal Castle of Rothesay was erected by an alien and an invader, and

must have stood for many years as a sign of the subjection of the natives

to a foreign yoke. Yet those jovial fair-haired Norwegians were no

ascetics, but bold, free-handed, and frank, as befitted the warriors whose

"march was o’er the mountain waves," whose "home was on the deep." And

these old walls, in their earliest days, must have witnessed many a scene

of "gamyn and glee," and resounded upon festive occasions with "mirth and

youthful jollity." For we know the method of the Norwegian rover’s life

from the Saga of King Olaf—

"The guests were loud, the

ale was strong,

King Olaf feasted late and

long;

The hoary Scalds together sang,

O’erhead the smoky rafters rang."

And with some such rites as

these was the baptism of Rothesay Castle accomplished in those distant

times.

Some romantic theorists

assert that the true meaning of Rothesay in Gaelic is "Wheel of Fortune,"

and state that this name was bestowed upon it in consequence of the rapid

changes which took place in the possession of this ancient fortalice. The

original appellation given to it by its Norwegian founders is now unknown;

but the study of its history sufficiently justifies this fanciful title,

as shall now be related.

The topographical position

of many of our Scottish Castles made them historical, even though they had

no intrinsic claim upon the historian. The names of many of them are

preserved, not so much in consequence of their importance as because they

occupied debatable land, upon which opposing armies continually met to

decide their contests. Such a position did Rothesay Castle occupy.

Situated at the entrance to the estuary of the Clyde, and possessing a

well-sheltered harbour and good post of observation, it was naturally one

of the coveted spots which attracted the attention of the northern

invaders. The Norwegians and Danes, who successively over-ran the coasts

of Scotland, were not ignorant of the advantages possessed by the hold of

this fort, and thus it happened that many a bloody fray took place beneath

its walls. And so, for a hundred and fifty years after its erection the

Castle changed hands frequently, until it came at length into the power of

the Norwegians after a protracted siege.

The native Scots had not

sufficient strength to dislodge them from this coign of vantage, and when

Hako, the Dane, led his great Armada into the Firth of Clyde, he found in

Rothesay a safe harbour for his fleet, and a strong fortress for his

protection. Warily extending his conquests, he took possession of Arran

and the Cumbraes, preparatory to making a descent upon the mainland; and

gathering together the combined forces of Norway and Denmark, he landed on

the Ayrshire coast immediately opposite Bute. But the young King,

Alexander III., had already aroused the Scottish peoples to resistance,

and, marching himself at the head of his army, he met the invaders at

Largs, but a short distance from their point of landing.

The fortunes of war were

not soon decided, as neither party gained palpable advantage over the

other; and so the battle was renewed upon three successive days. But,

Neptune and Ćolus, the gods of the Sea and the Wind, came to the aid of

Britain, as they did three centuries later against the Spanish Armada of

Philip II. The wild nor’-east wind sweeping down the Firth, and lashing

the troubled waters into fury, drove the Danish ships from their

anchorage, and dashed them helplessly upon the unfriendly shore. The noble

barks, which had withstood the gales of many years, were powerless in the

narrow, unknown channels in which they were drifting; and the Danes found

in their melancholy experience that neither the winds nor the waves would

obey them.

The Scots were active in

taking advantage of this occasion; and they drove the too-confident

invaders ignominiously from their coasts. Hako retired with difficulty,

taking the remnant of his army to Orkney; and there, lamenting the flower

of his warriors and his own near kinsmen slain in this disastrous

conflict, he finally expired, the victim of grief and despair. Thus ended

the Battle of Largs, the last contest betwixt the Scots and Danes upon our

native soil. Nearly six centuries after, the descendants of those warriors

met in widely-diverse circumstances. Then "mighty Nelson" led his fleet

through the waters of the Baltic to the very walls of Copenhagen, and

proved to the successors of the Vikings of old that their rule over the

ocean was at an end. And if Hako mourned in defeat the brave army which he

left shattered and destroyed on the shores of the Clyde, not less, even

when crowned with victory, should we—

"Think of those who

sleep

Full many a fathom deep,

By thy wild and stormy steep,

Elsinore."

After the Battle of Largs,

the Castle of Rothesay was garrisoned by the troops of King Alexander, and

the Scots remained in possession of it until the faint-hearted John Baliol

surrendered it to Edward of England, as an atonement for his heinous crime

of independence. But the valour of King Robert the Bruce freed Scotland

from the presence of the English soldiers for a time, and he regained the

Castle. Scottish politics became confused after his death; and when

Randolph, the Regent, died, affairs reached a crisis. Edward Baliol,

collecting a scratch army in England, took advantage of the prevailing

confusion, and made a rapid descent upon Scotland. His attempts were

crowned with success, however undeserved; and as the young King, David

Bruce, had been hastily conveyed to Dumbarton Castle, as a place of

security, the invader followed him closely, and took the Castle of

Rothesay with ease. His army, however, was not of sufficient strength to

enable him to garrison this stronghold, and it soon submitted to the

partisans of the King. And when, some fifty years later, the troubled

state of Scotland had been somewhat allayed, the beauty of the surrounding

country and the salubrity of the climate, which had not been noticed in

warlike times, then attracted attention. Robert II., the first of the long

line of Stewart Kings, visited the Castle upon several occasions, and

latterly selected it as his residence.

After his death his son

John, who ascended the throne under the title of Robert III., continued to

hold Rothesay in favour; so much so that he conferred the title of Duke of

Rothesay upon his eldest son, making this an hereditary title for the

heir-apparent. Hence the Prince of Wales, who is Duke of Cornwall, and was

Earl of Dublin in Ireland, is Duke of Rothesay and Baron Renfrew in

Scotland. The fate of the first Duke of Rothesay could not be regarded as

a good augury by his contemporaries. The mild King Robert III., unfitted

by an accident in early youth from mingling in the warlike employments of

the time, was possessed of a mind more inclined to religious melancholy

and austerity than chivalrous bravery. It was, therefore, with deep regret

and pain that he heard of the wild and licentious character of his son,

the new Duke of Rothesay. The restraint imposed on this unhappy young man

by the influence of his mother had been withdrawn at her death; and he had

given loose rein to his passions, and would abide no rebuke. The King, his

father, was weak enough to allow his own brother, the wily Duke of Albany,

to poison his mind against Rothesay. So great an influence did Albany gain

over the King that he finally obtained permission to confine Rothesay in

close ward.

The Duke of Albany lost no

time in putting this power into practice; with the assistance of an

unprincipled retainer he seized his nephew and conveyed him to his own

Castle of Falkland, where Rothesay was enclosed in one of the darkest

dungeons, and refused the ordinary necessaries of life. Many strange

stories are told regarding this inhuman treatment. It is said that one of

the female servants assisted to keep him in life by dropping meal into his

prison-chamber through the crevices of the floor above; whilst another

bestowed upon him a portion of the provision which Nature had made for the

support of her own children. Rothesay’s unnatural uncle, having discovered

the sources of this succour, ruthlessly put both of these ministering

angels to death. When life became insupportable, the unhappy youth was

relieved from his misery by welcome death, after enduring the most fearful

torture of which the human frame is capable. His body was quietly conveyed

to Lindores Abbey and buried there, and his ambitious uncle found himself,

by his machinations, one step nearer to the throne. The title of Duke of

Rothesay was transferred to his brother James, who afterwards ascended the

throne as first of that name, and closed an unhappy life by a violent

death.

After the murder of the

first Duke of Rothesay, his father, King Robert, fearful that a similar

fate might befall his only remaining son, resolved to send him to France

for safety. But the ship in which the Duke sailed was captured by an

English vessel, and the Prince was sent into captivity in London. The news

of this fresh calamity fell with crushing weight upon the old King, and

brought him, heart-broken, to his grave; for, like Israel of old, he may

have said, "If I am bereaved of my children, I am bereaved." And as

the night of sorrow closed around him in his Castle of Rothesay, and he

thought of one son murdered and another in hopeless captivity, whilst the

brother, to whom he had trusted all, had proved faithless and untrue,

death must have seemed a glad release to him from the life-long trouble he

had endured.

It must not be imagined

that there are no pleasant episodes connected with Rothesay Castle. There

is a story told of an unwilling visit paid to it by James V., which is not

a little amusing. That merry monarch, whilst still "the Guidman of

Ballengeich," had often gone in quest of amorous adventures, but at length

he resolved to settle down to serious matrimony, and set forth, like

Cślebs, in search of a wife. An intimate connection had ever been

maintained betwixt Scotland and France, and as a union with that country

was most desirable, James naturally turned his thoughts in that direction.

But the reformed doctrines had made many converts in Scotland, and the

nobles looked with disfavour upon a project which might place them at the

mercy of the ultra-Roman Court of France. James was self-willed, however,

and would not be diverted from his purpose. He sailed from Leith,

therefore, with the avowed intention of wedding a French Princess, despite

remonstrances of his advisers.

The weather was propitious,

and with "youth at the prow and pleasure at the helm," his noble bark

sailed onwards. But the grim Scottish Barons performed the journey most

unwillingly, and at length laying their heads together, they resolved to

trick the King out of his purpose.

One night whilst he was

asleep they persuaded the captain to put about ship and to run back to

Scotland. Whilst their unconscious victim was peacefully dreaming of love

and joy in France, his ship was speeding fast homewards and placing the

rolling sea betwixt him and his hopes. Judge then of his surprise and

indignation when he awoke to find that the distance between him and love

was increasing rather than lessening, and that the power over his actions

had been usurped by his officious advisers. He raged and stormed, and

swore most likely (for at that time to "swear like a Scot" was a saying on

the Continent), and vowed to punish the whole body of traitors who had

dared to coerce him. Against the captain especially was his wrath turned,

for the historian of the incident relates that "had not beine the earnest

solisitatioun of monie in his favours he had hanged the skipper

incontinent."

To vindicate his power he

ordered them again to change their course, and selecting Bute as his

resting-place, he remained for some time in the Castle of Rothesay, until

preparation had been made to convey him to Stirling. Like all his race,

this headstrong Prince became violent under opposition; and as though

influenced irresistibly by the magnet of love, he rested not until he had

set out again to wed a damsel whom he had never seen. The unhappy Queen

Magdalene, daughter of the King of France, whom he brought back to

Scotland, survived her nuptials only forty days; and shortly afterwards

James journeyed again to France upon a similar errand, returning with Mary

of Guise as his bride, the mother of the un-fortunate Mary, Queen of

Scots.

During the disturbed reign

of Charles I., the Castle of Rothesay was garrisoned in the interests of

the King by its hereditary custodian, Sir James Stewart of Bute; but no

serious engagement took place there, and the troops were despatched to aid

the royal cause in other parts of the kingdom. When Cromwell entered

Scotland he caused the soldiers of the Commonwealth to take possession of

Rothesay Castle, probably anticipating that the resistance of the Highland

Clans would be focussed there; and as he did not care to leave a garrison

so far from his main army, he instructed his men to destroy the strongest

parts of the edifice. The command was faithfully obeyed by the

Independents, to whom the demolition of Cathedral or Castle seems to have

been alike palatable. And Rothesay, which had been a tower of strength for

nearly six centuries, never again held its head aloft in proud defiance.

The old saying that "Time

tries all," applies to Rothesay Castle, which was now drawing to the end

of its existence as a royal residence. The Stewart line, the members of

which had been its first patrons, had fallen upon evil days. Charles I.

was beheaded; Charles II. died without legitimate heir; and the turbulent

reign of the Duke of York (James VII.) had spread dismay amongst the

majority of the Scottish nation. Many of the Covenanting nobles had found

refuge at the Court of William of Orange, and chief among them was the

unfortunate Earl of Argyll, who, by a most iniquitous sentence, had been

attainted and outlawed. The plots of William of Orange against his

father-in-law, then styled "James II. and VII.," afforded opportunity for

the malcontents. The growing feeling of dissatisfaction encouraged the

expatriated noblemen to attempt a rising against the Government; and the

joint-expeditions of the Duke of Monmouth and the Earl of Argyll were

organised. It was proposed that the former should land on the southern

shores of England while the latter made a diversion by invading the

northern part of the kingdom. In June 1685, Monmouth landed in Dorset, and

speedily drew a formidable following to his standard; but the rash

encounter which he dared at Sedgemoor finally overthrew him, and awoke the

vengeance of a ruthless government.

Argyll’s expedition had no

more fortunate issue. The leaders had disputed as to the proper point of

attack; and in the multitude of counsellors there is danger. Argyll

insisted upon landing in his own country, while some of the Lowland nobles

more reasonably proposed to win over the landed proprietors in the south

of Scotland by force or persuasion. A compromise was finally adopted

whereby the first landing was arranged to take place m Argyll, but the

attack to be directed against the rich counties bordering upon the Clyde.

Landing in Cantyre, the little army was soon increased by the Campbell

Clan; and, taking possession of Rothesay Castle, they fortified it,

storing the ammunition upon one of the small islands in the Kyles of Bute.

But the irresolution of the Earl proved the destruction of the army. Urged

by the confederated leaders to advance and give battle, he at last

consented to move the troops into the Lennox country, but here, when in

the presence of the enemy, his courage forsook him, and he declined to

risk an encounter. There is often as much skill in avoiding a contest as

in daring it; but Argyll could neither lead an assault nor conduct a

retreat, and his army was soon dispersed without having endured an

engagement. He was himself taken as a fugitive, and as he had been

sentenced to death in 1681, he was executed in 1685 without another trial,

though he had again been a rebel— an instance of the vindictive rigour of

the time.

Meanwhile the stores which

Argyll had laid up near Rothesay were taken by the King’s soldiers, and

his brother, Lord Niel Campbell, whom he had left at the Castle, made his

escape from the island of Bute, destroying the fortress ere he fled, and

leaving little to the conquerors save the blackened and charred ruins

which now remain. And thus, after a long and honourable career, this noble

pile closed its history in no memorable conflict, nor amid the din of

contending hosts, but during the tumult of a sham revolt the torch of the

incendiary was applied to the structure in wanton malice by the hand of a

Scottish nobleman. The third Marquess of Bute (1847-1900) did much to

restore the outer portion of the Castle, the changes made by him being

shown by the use of red sandstone, so that they may be easily

distinguished. |