|

CANADA'S DEBT TO THE FUR

COMPANIES

THE infant life of

Canada was nourished by the fur traders. The new impulse given to

France in the last year of the sixteenth century by Chauvin's

charter to trade for furs held within it untold possibilities for

the development of Canada. French gentlemen and soldiers came forth

to the New World seeking excitement in the western wilds, and hoping

also to mend their broken fortunes. There were scores of such at

Quebec and Montreal, but especially at Three Rivers on the St.

Lawrence. Nicolet led the way to the fur country; Joliet gave up the

church for furs; Duluth was a freebooter, and the charge against him

was that he systematically broke the king's ordinance as to the fur

trade; La Salle sent the first vessel—the Griffin—laden with furs

down the lakes, where she was lost; the iron-handed Tonty deserted

the whites and threw in his lot with the Indians as a fur

trafficker; and La Verendrye, one of the greatest of the early

Frenchmen charged with making great wealth by the fur trade, says in

his heart-broken reply to his persecutors: " If more than 40,000

livres of debt which I have on my shoulders are an advantage, then I

can flatter myself that I am very rich."

Shortly after French

Canada became British, it was seen that so lucrative a traffic as

that in pelts should not be given lip. Curry, Finlay and Henry, sen.,

pluckily pushed their way beyond Lake Superior iii search of wealth,

and found it. The Montreal merchants trade the trade up the lakes

the foundation of Montreal's commercial supremacy in Canada; and the

North-West Company, which they founded, only did what the great

English company had been doing with their motto, "Pro pelle cutem "

for a hundred years on the shores of Hudson Bay.

It is evident to the

most casual observer that the fur trade was an important element in

the building up of Canada, not only in wealth but also in some of

our higher national characteristics. The coureurs de bois and the

canoemen stood for much in the days of our infancy as a new nation.

While we delight to

see the sonorous Indian words chosen as the names for our New World

rivers and lakes, counties and towns, yet we rejoice too that our

pioneers are thus commemorated. The naives of all the French

pioneers mentioned are to be found fastened on the region which they

explored. Fraser, Thompson, Stuart, Quesnel, Douglas, Finlayson, and

Dease have retained their hold even in the face of such musical

terns as Chipewyaan, Metlakalitla, Assiniboine, and Muskegon.

Winnipegosis and Manitoba forts have borne the names of our three

traders, Mackenzie, Lord Selkirk, and Simpson, and Fort Alexandria

also commemorates the first of these. Rivers and islands, counties,

towns, mountains and vast regions of territory are all known by the

names of the trio whose fortunes we have been following.

The great explorer

leads the way for the development of his country, stimulates inquiry

as to the resources of the land lie finds, and awakens the desire in

other breasts to follow if not excel him in his discoveries. The map

maker, the mineral prospector, the lumberer, and the tourist are all

dependent on him as their guide. What Columbus is to the New World

as a whole, the explorer is to the special field he discovers, and

his fame, if not so great, must yet be akin to that of the man who

ploughed the first furrow across the Atlantic.

The fur trader is

also the pioneer of settlement. It is quite true that there is an

antagonism between the fur trader and the settler. The fur trader

seeks to keep the beaver, the mink, and the fox alive that he may

take toll of them year after year; when the settler comes the beaver

dam is a thing of the past, and the fox flees far away to his forest

lair. Yet inasmuch as the settler is permanent, and the trader

transient, the meeting of the two has the inevitable result of

driving off the trader. This cannot be helped, it is the trader's

misfortune; he must find "fresh woods and pastures new," and then

when his fur-trading days are done he must resort to the life of the

settler and spend the sunset of his days in village or clearance.

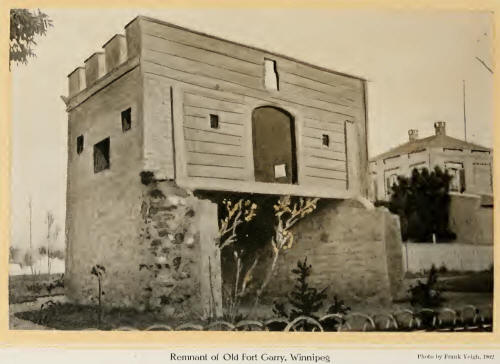

It was'the old Hudson's Bay Company led by Lord Selkirk that

introduced the Highland settlers on Red River, and decreed that Fort

Garry should be the centre around which gathered the Red River

Settlement, which in time became the city of Winnipeg. Fort Victoria

on Vancouver Island, chosen by Trader James Douglas as the depot of

the fur trade, has become the capital of British Columbia and the

gem of the Pacific coast. All over Rupert's Land the places chosen

by the fur traders have become the centres where has grown tip the

trade of to-day. Portage la Prairie was a fort, so was Brandon, so

was Qu'Appelle, so was Edmonton, so was Fort William, and many

others. In hundreds of cities on the American continent the old fur

traders' fort was the first post driven down to mark the

establishment of the commerce of the future day.

Sir George Simpson

fought a losing battle when he sought to keep a Chinese wall round

his fur preserve. It was impossible to maintain this splendid

isolation. Prejudice, misrepresentation i, charter rights, and rocky

barriers could not stop the inevitable movement. The sleepy fur

trader in his dream hears approaching the sound of the bee—"a more

adventurous colonist than man"—and mutters in his sleep:—

"I listen long

To his domestic hum, and I think I hear

The sound of that advancing multitude

Which soon shall fill these deserts."

It must be so!

No country was ever

iii the position to need the fur trade in its early history as much

as old Canada. Early Canada was covered with heavy forests. The St.

Lawrence, its chief artery, was difficult to navigate. Its first

colonists were all poor—fleeing away from the despotic persecution

of victorious American revolutionists, leaving everything behind

them, or crossing the Atlantic because of hard financial conditions

in the motherland. Moreover, Canada is northern and nature is not so

prolific as she is further south. Hence long years elapsed before

poverty was driven out, and peaceful plenty came.

Now the northerly

situation of Canada was very favourable for the production of

fur-bearing animals. Furs are very valuable, and are so light and

may be contained in such small space that the trapper may carry a

fortune in one single pack upon his back. This made trade possible

over thousands of miles to the interior, through the agency of the

birch-bark canoe, which the redman so valued as to call it the gift

of the maniton. So while fifty years were passing in Little York

(Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada, with the most painful and

slow steps of improvement, Montreal was the mart of a most valuable

trade. The fur-trading merchants became nabobs. Forsyth, Richardson,

McTavish, Frobisher and many others became wealthy, bought

seigniories, became prominent figures in public life, were looked up

to as their natural leaders by their French-Canadian voyageurs, and

retired from business to live in their palatial abodes---the "lords

of the north"—or to retire as did Sir Alexander Mackenzie and others

to the motherland and spend their remaining days as country

gentlemen.

The same thing has

continued from the earliest days till now. Not only can a an of fair

education, who rises with reasonable rapidity in his forty years or

more of service for the company, have at the end of his time -say

from six to eight thousand pounds sterling, but clerks,

post-masters, and labouring-men may all leave the service with

proportionate savings. True the life may be long, hard, and

unattractive, but expenses are small and savings large. The Red

River Settlement grew to twelve thousand people in 1870, five-sixths

of its people having come through the channel of the fur trade.

No doubt in the

present condition of Canada the fur trade does not occupy so

important a place. The farmer tends to overtake the hunter in

fortune, just as the settler must in time drive out the trader. But

the very greatest service was rendered the country by the fur

traders in early Canada supplying a class of capitalists who spent

their money in giving employment to others, organized first lines of

transport by boat, filled the sea with their sailing vessels to

carry freight and passengers, and afterwards introduced steamships

to thread the rivers, cross the lakes and even the Atlantic Ocean.

Montreal became a

centre for wholesale trade. Goods could be supplied to the settlers

in Western Canada; then when transport of a better kind was needed,

the capital and energy of Montreal merchants became the basis for

building lines of railway, and for giving the farmer with his

products access to the great markets of the world. The chain of

connection is complete in Canada between the fur trader's pioneer

work and the present state of Canadian trade and commerce.

The fur trade was

also a school for the development of such high moral qualities as

courage and tact. In no other circumstances does so much depend upon

the personal qualities of the man. The fur trade is carried on in

the solitudes, far from organized society. The dealings are with

savages who are kept down by no visible authority, who are ignorant

and may be appealed to by greed, jealousy, or superstition to turn

against the trader and injure him. Thus it was often dangerous to go

far from the base of supplies and venture almost single-handed among

untutored tribes.

The experiences of

the fur companies in such circumstances have been very remarkable.

At first there may have been violence done by the natives to the

traders. The brothers Frobisher on their first visits to Rainy Lake

were robbed, the ship Tonquill on the Pacific coast was attacked and

many employes killed, massacres of the traders took place at Fort

St. .John and Kamloops in British Columbia, and Chief Factor

Campbell was attacked in his occupation of the head waters of the

Stikine and on the Upper Yukon. Yet it is marvellous that for more

than two centuries, or including the French regime, three centuries,

the traders have freely mingled with the savage tribes and have been

objects of envy from their possession of valuable goods, but have

succeeded by sturdiness and good management in getting control of

the wildest Indians.

Now this was chiefly

accomplished by the good character of the traders. The men of the

Hudson's Bay Company especially, but to a certain extent also all

the fur traders of British America have been men of probity and

fairness. Just and honest treatment of an Indian snakes him your

friend. The terrible scenes of bloodshed enacted by the Indians

among the Americans in the \'Western States can, in almost every

instance, be traced to dishonesty and wrong on the part of the

traders and Indian agents of that country. British fur companies

have been, on the whole, dominated by a wise desire to retain the

confidence of the Indian, and have proved the statement true that

Britain alone has shown an ability to deal justly with and to gain

the confidence of inferior races.

In reaching this end

great determination, watchfulness, and caution are developed in the

trader. He must be firm, must never let an Indian imagine he can

master him, and many a time must be ready to use the "knock-down"

argument in the case of the impudent or the intractable. Physically

and mentally the successful trader requires to be a man among men.

Thus the fur trade has cultivated a manliness, straightforwardness,

and decision of character which has proved a heritage of greatest

value to the Canadian people.

Wherever the Hudson's

Bay Company fort is established there flies the Union Jack. On

Sundays and holidays it was always unfurled, and the lesson that

there was something higher thane trade was thereby taught, for on

those days traffic ceased. The companies were always on the side of

law and order. The loyal sentiment was their only way of governing

the Indians, and it became a part of their settled policy to "honour

the king." In the War of the Revolution the traders along the

frontier were true to Britain, and the celebrated capture of

Michilimackinae in 1812 was accomplished by a British force of less

than two hundred men---one hundred and sixty of them Nor'-Wester

voyageurs under Captain Roberts. In the struggle of the Canadian

rebellion we have seen that from Governor Simpson down all the fur

traders were against rebellion and in favour of law.

Undoubtedly

hand-in-hand with the United Empire Loyalists, the Nor'-Wester

influence did much to keep Canada true to British institutions,

while the presence of the Hudson's Bay Company and the Selkirk

colony in Rupert's Land, and the traders led by Chief Factor James

Douglas on the coast, were the means of preserving to the British

Crown the greater Canada which was an object of desire for half a

century to the Americans. The traders did their full share in

maintaining and perpetuating the loyalty which to-day is so strong a

sentiment in the breasts of Canadians. |