|

STRUGGLE OF THE FUR

COMPANIES

"I SING arms and the

hero," the words used by Virgil to introduce his great story of

valour and heroism in the far Mediterranean may be as truly applied

by us in beginning an account of deeds and men in the rise and

struggles of frontier life in the far west of North America. The

picturesque and heroic are not confined to any age or clime; indeed,

they are characteristic in a peculiar degree of the early days of

occupation of the American continent. The conflict of the two great

cur companies, which carried on a trade covering the vast expanse of

British North America, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific

Oceans, brings before us operations extending over distances before

which Ceasar's invasions or even Alexander's great marches shrink

into insignificance.

The now venerable

Hudson's Bay Company, which we recognize to-day as having a history

of two and a quarter centuries, had spent the first century of its

rule satisfied with its place of pre-eminence on the shores of

Hudson Bay, had declared several enormous dividends, and had begun

to consider its right prescriptive to the trade brought by the

Indians down the rivers, even from the Rocky Mountains, two thousand

miles to the west. It was a beautiful thing to see the fealty with

which the northern Indians, the Crees and Chipewyans, and the

Eskimos as well, regarded the English traders, and brought to them

at York Factory and Fort Churchill the marten, fox and beaver skins

caught, by their shrewdness and ceaseless energy, on the rivers and

in the forests of the vast interior. The taking of French Canada by

the English relieved the company for one or two decades from any

show of competition which may have affected them on their southern

border during the French regime.

But as Canada began

to receive adventurous spirits from Scotland, England, and the

American colonies, it became evident to the traders of Hudson Bay

that new opponents not to be despised would have to be met and dealt

with. The Scottish merchants of Montreal, many of whom had the blood

and spirit of the Highland clans that had fought at Culloden, and

Englishmen, who had braved the hardships of the American frontier

and had come to Canada to try their fortunes, looked towards the fur

country as a new field for adventure and profit. Men of this class

are proverbially men of daring and of self-confidence. In frequent

contact with the Indians, encountering the big game of the Woods,

crossing deep rivers, and running dangerous rapids, accustomed, in

short, to all the hardships of the border country, the frontiersman

is full of spirit and resource.

Accordingly, a few

years after the conquest, Curry, Finlay, Henry, sen., and many

others whose names are well known, started from Montreal with their

companies of Indians and French-Canadians, and, going up the Ottawa

River and Great Lakes, fixed their eyes on the star of hope in the

far north. Verendrye, a French explorer, had led the way inland from

Lake Superior, thirty or forty years before, though he and his

followers had never gone north of the Saskatchewan. The merchants of

Montreal thought nothing of penetrating farther to the north; so,

leaving the Saskatchewan behind, they planned a flank movement on

the Hudson's Bay Company, which would completely cut off from them

the great bodies of Indians who came down the English River or the

Saskateliewan to the forts on Hudson Bay.

True, a few years

before this plan was undertaken, the Hudson's Bay Company, no doubt

preparing to gird itself for the fray, had sent an ardent explorer,

Samuel Hearne, afterwards known as the "'Mungo Park' of Canada," to

explore the interior, conciliate the Indians, and ascertain the

possibility of increasing trade. After two absolute failures, Hearne

gained, on his third journey from Hudson Bay, Lake Atliapapuskow,

probably Great Slave Lake; and, going north-eastward, he discovered

the Copper Mine River, and reached the shore of the Arctic Sea. This

was a worthy achievement, and it was three years after this that

Thomas and Joseph Frobisher, two merchants from Montreal, in

furtherance of the plan spoken of, built (1772) a fur trader's fort

at Sturgeon Lake on the Saskatchewan River, where the northern lakes

and watercourses make a connection with the Churchill or English

River, which runs down to Hudson Bay.

This was a strategic

point of first importance. North, east, and west it commanded the

approaches; and it was a stroke of genius when the brothers

Frobisher erected their simple log fort at this point, and prepared

to wage a war worthy of the giants. Hearne and his colleagues at

Fort Churchill were not long in hearing of the intruders and their

plans; in fact, friendly Indians in a single season blazed the news

on the very shore of Hudson Bay. Hearne lost no time in taking up

the gage of battle thrown to him by the Frobishers. Going to Pine

Island Lake, the western arm of the Sturgeon, within five hundred

yards of the fort built by the Montrealers, he began (1774) the

erection of Fort Cumberland, a trading-post well known to the

present day.

It was a fateful year

when first two forts, the embodiment of rival interests, stood face

to face, a few hundred yards apart, on the Saskatchewan River, the

great artery of Rupert's Land. Then and there was begun a conflict

which for well-nigh half a century stirred the passions of violent

and headstrong Then, urged to its height one of the most celebrated

competitions of modern times, introduced the fire-water—the curse of

the poor Indian —as a means of advancing trade, and dyed with the

blood of some of the best men of both companies the snows of

Athabaska, the banks of the Saskatchewan, the rocky shores of Lake

Superior, and the fertile soil of the prairies on the Red River of

the North.

At the very time when

the thirteen English colonies on the Atlantic shore were

precipitating a fratricidal conflict, in which families were

divided, neighbours alienated, and English-speaking colonists

separated into hostile camps, in the far north a company of

Englishmen from Hudson Bay were turning their weapons against

Englishmen in Canada, both speaking the salve tongue, respecting the

same laws, and flying the same flag.

Seventeen hundred and

seventy-four and its succeeding years thus presented the sad

spectacle of Anglo-Saxon interests, both in the Atlantic colonies

and in Rupert's Land, in a state of fiercest conflict and division,

from the tropics to the Arctic circle, from the Gulf of Mexico to

the icy sea.

The Hudson's Bay

Company had been averse to entering on a conflict which promised to

be so severe and destructive of successful trade, but the Montreal

traders were aggressive. Frobisher's men had penetrated to Lake

Athabaska and built forts in the surrounding region. But the English

company, with enormous energy, pushed forward its plans and built

its forts. It took hold of the Assiniboine and Red River country,

and built famous forts, such as Brandon House, Edmonton House,

Carlton House, and trading-posts at the mouth of Winnipeg River, on

Rainy Lake, and even in the country now included in Minnesota. The

great distance of these trading-houses from each other well shows

how thoroughly the Hudson's Bay Company had covered the country, for

each of these centres carried with it a number of subordinate posts.

The Montreal traders

were no less energetic. In fact, though the Hudson's Bay Company had

a higher reputation with the Indians, and though the English company

could reach the interior earlier in the spring, yet the dash and

spirit and acquaintance with the country of the Canadian traders

made them, in organization and trading ability, more than a match

for their rivals. Finding the need of strengthening themselves, the

several firms of merchants who were trading from Montreal agreed to

unite in 1783-4. The prospect of peace and cooperation was, however,

immediately destroyed by some of the selfish and unworthy elements

of the new company breaking away from it, and with the help of other

Montreal merchants organizing an opposition.

Four years afterwards

a cruel murder was perpetrated in the Saskatchewan region, by Pond,

the marplot who had divided the company, and so great was the fear

and confusion caused by this act that the three Montreal companies

effected a union in 1787 into one North-West Company. New posts and

a great impulse to trade resulted from this union. The trade, which

at the time of union amounted to £40,000, by the end of the century

had increased to three tinges that sum. The last quarter of the

eighteenth century thus saw the English and the Canadian fur

companies, side by side, occupying the vast interior of Rupert's

Land, and even crossing the Rocky Mountains in search of trade.

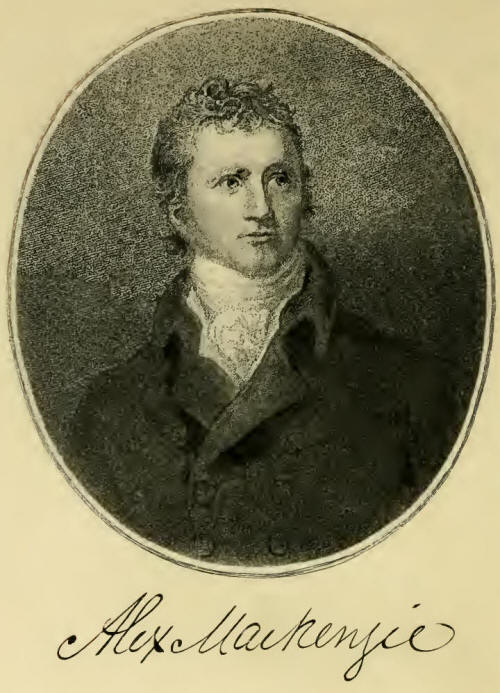

Into the Canadian

company, among the young Scotsmen who were attracted to Canada by

the fur trade, entered a young Highland adventurer, Alexander

Mackenzie by name. He at once rose to prominence, and became a

determined and perhaps rather aggressive and irreconcilable element

among the Nor'-Nesters in the Protean phases of their exciting

history. The nineteenth century had just dawned as Alexander

Mackenzie published in London an account of his great discovery. The

book had ardent readers in Great Britain. One of these was a young

Scottish nobleman, Thomas, Earl of Selkirk, who had a lofty

imagination and a high public spirit. The book of travels excited in

the young peer the spirit of adventure, and led to his embarking on

a great scheme of emigration. In a few years, to further his

emigration plans, Lord Selkirk gained a controlling interest in the

Hudson's Bay Company, being opposed in this by Alexander Mackenzie,

who held a quantity of stock in the English company. [The second

part of this book narrates in detail the circumstances connected

with Lord Selkirk's great project.] Lord Selkirk organized his

colony under the auspices of the Hudson's Bay Company, though

opposed by Mackenzie and others of the Nor'-Westers. But, as we

shall presently learn, colonizer and fur trader could not at all

agree. Their aims, methods, and interests were not to be reconciled,

and blood ran plentifully on the bleak plains of Rupert's Land to

the disgrace of both parties, who claimed the shelter of the British

flag.

The imperial and

Canadian authorities were both compelled to interfere. Lord Selkirk,

wearied and harassed by conflicts, lawsuits, and misunderstandings,

returned home to die. With sympathetic interest in this conflict

from the other side, Alexander Mackenzie, far away in Britain, spent

his declining years, until, in the same year, (1820) the opposing

leaders passed away.

The following year

saw more peaceable counsels prevail, and the two companies united

under the name of the older organization as the Hudson's Bay

Company. Just as the union was effected a new force appeared in the

trader's clerk, George Simpson, who, as governor, was destined to

unite the discordant elements, and in a career of nearly forty years

to raise the united companies to a position of greatest influence.

We ask the patient

attention of our readers, as with some detail we set forth the life,

work, and influence of these three representatives of the great fur

companies, viz., Sir Alexander Mackenzie, the Earl of Selkirk, and

Sir George Simpson. |