Transfer Act passed—A moribund government—The Canadian surveying

party—Causes of the rebellion—Turbulent Metis—American

interference—Disloyal ecclesiastics—Governor McDougall— Riel and

his rebel band—A blameworthy Governor—The "blawsted

fence"—Seizure of Fort Garry—Kiel's ambitions—Loyal rising—Three

wise men from the East—The New Nation— A winter meeting—Bill of

Rights—Canadian shot—The Wolseley expedition—Three renegades

slink away—The end of Company rule—The new Province of Manitoba.

The old Company had agreed to the bargain,

and the Imperial Act was passed authorizing the transfer of the

vast territory east of the Rocky Mountains to Canada. Canada,

with the strengthening national spirit rising from the young

confederation, with pleasure saw the Dominion Government place

in the estimates the three hundred thousand pounds for the

payment of the Hudson's Bay Company, and an Act was passed by

the Dominion Parliament providing for a government of the

north-west territories, which would secure the administration of

justice, and the peace, order, and good government of Her

Majesty's subjects and others. It was enacted, however, that all

laws of the territory at the time of the passing of the Act

should remain in force until amended or repealed, and all

officers except the chief to continue in office until others

were appointed.

And now began the most miserable and disreputable exhibition of

decrepitude, imbecility, jesuitry, foreign interference,

blundering, and rash patriotism ever witnessed in the fur

traders' country. This was known as the Red River rebellion. The

writer arrived in Fort Garry the year following this wretched

affair, made the acquaintance of many of the actors in the

rebellion, and heard their stories. The real, deep significance

of this rebellion has never been fully made known. Whether the

writer will succeed in telling the whole tale remains to be

seen.

The Hudson's Bay Company officials at Red River were still the

government. This fact must be distinctly borne in mind. It has

been stated, however, that this government had become hopelessly

weak and inefficient. Governor Dallas, in the words quoted,

admitted this and lamented over it. Were there any doubt in

regard to this statement, it was shown by the utter defiance of

the law in the breaking of jail in the three cases of Corbett,

Stewart, and Dr. Schultz. No government could retain respect

when the solemn behests of its courts were laughed at and

despised. This is the real reason lying at the root of the

apathy of the English-speaking people of the Red River in

dealing with the rebellion. They were not cowards; they sprang

from ancestors who had fought Britain's battles; they were

intelligent and moral; they loved their homes and were prepared

to defend them; but they had no guarantee of leadership; they

had no assurance that their efforts would be given even the

colour of legality; the broken-down Jail outside Fort Garry, its

uprooted stockades and helpless old Jailor, were the symbol of

governmental decrepitude and were the sport of any determined

law-breaker.

It has been the habit of their opponents to refer to the

annoyance of the Hudson's Bay Company Committee in London with

Canada for in 1869 sending surveyors to examine the country

before the transfer was made. Reference has also been made to

the dissatisfaction of the local officers at the action taken by

the Company in dealing with the deed poll in 1863 ; some have

said that the Hudson's Bay Company officials at Fort Garry did

not admire the Canadian leaders as they saw them; and others

have maintained that these officers cared nothing for the

country, provided they received large enough dividends as

wintering partners.

Now, there may be something in these contentions, but they do

not touch the core of the matter. The Hudson's Bay Company, both

in London and Fort Garry, wore thoroughly loyal to British

institutions; the officers were educated, responsible, and

high-minded men ; they had acted up to their light in a

thoroughly honourable manner, and no mere prejudice, or fancied

grievance, or personal dislike would have made them untrue to

their trusts. But the government had become decrepit;

vacillation and uncertainty characterized every act; had the

people been behind them, had they not felt that the people

distrusted them, they would have taken action, as it was their

duty to do.

The chronic condition of helplessness and governmental decay was

emphasized and increased by a sad circumstance. Governor William

McTavish, an honourable and well-meaning man, was sick. In the

midst of the troubles of 1863 he would willingly have resigned,

as Governor Dallas assures us ; now he was physically incapable

of the energy and decision requisite under the circumstances.

Moreover, as we shall see, there was a most insidious and

dangerous influence dogging his every step. His subordinates

would not act without him, he could not act without them, and

thus an absolute deadlock . ensued. Moreover, the Council of

Assiniboia, an appointed body, had felt itself for years out of

touch with the sentiment of the colony, and its efforts at

legislation resulted in no improvement of the condition of

things. Woe to a country ruled by an oligarchy, however

well-meaning or reputable such a body may be!

Turn now from this picture of pitiful weakness to the

unaccountable and culpable blundering of the Canadian

Government. Cartier and McDougall found out in England that

sending in a party of surveyors before the country was

transferred was offensive to the Hudson's Bay Company. More

offensive still was the method of conducting the expedition. It

was a mark of sublime stupidity to profess, as the Canadian

Government did, to look upon the money spent on this survey as a

benevolent device for relieving the people suffering from the

grasshopper visitation. The genius who originated the plan of

combining charity with gain should have been canonized.

Moreover, the plan of contractor Snow of paying poor wages,

delaying payment, and giving harsh treatment to such a people as

the half-breeds are known to be was most ill advised. The

evidently selfish and grasping spirit shown in this expedition

sent to survey and build the Dawson Road, yet turning aside to

claim unoccupied lands, to sow the seeds of doubt and suspicion

in the minds of a people hitherto secluded from the world, was

most unpatriotic and dangerous. It cannot be denied, in

addition, that while many of the small band of Canadians were

reputable and hard-working men, the course of a few prominent

leaders, who had made an illegitimate use of the Nor'-Wester

newspaper, had tended to keep the community in a state of

alienation and turmoil.

What, then, were the conditions? A helpless, moribund

government, without decision, without actual authority on the

one hand, and on the other an irritating, selfish, and

aggressive expedition, taking possession of the land before it

was transferred to Canada, and assuming the air of conquerors.

Look now at the combustible elements awaiting this combination.

The French half-breeds, descendants of the turbulent Bois Brules

of Lord Selkirk's times; the old men, companions of Sayer and

the elder Riel, who defied the authority of the court, and left

it shouting, "Vive la liberté!" now irritated by the Dawson Road

being built in the way Just described; the road running through

the seigniory given by Lord Selkirk to the Roman Catholic

bishop, the road in rear of their largest settlements, and

passing through another French settlement at Pointe des Chenes!

Further, the lands adjacent to these settlements, and naturally

connected with them, being seized by the intruders! Furthermore,

the natives, antagonized by the action of certain Canadians who

had for years maintained the country in a state of turmoil! Were

there not all the elements of an explosion of a serious and

dangerous kind? Two other most important forces in this

complicated state of things cannot be left out. The first of

these is a matter which requires careful statement, but yet it

is a most potential factor in the rebellion. This is the

attitude of certain persons in the United States. For twenty

years and more the trade of the Red River settlement had been

largely carried on by way of St. Paul, in the State of

Minnestota. The Hudson Bay route and York boat brigade were

unable to compote with the facilities offered by the approach of

the railway to the Mississippi River.

Accordingly long lines of Red River carts took loads of furs to

St. Paul and brought back freight for the Company. The Red River

trade was a recognized source of profit in St. Paul. Familiarity

in trade led to an interest on the part of the Americans in the

public affairs of Red River. Hot-headed and sordid people in Red

River settlement had actually spoken of the settlement being

connected with the United States.

Now that irritation was

manifested at Red River, steps were taken by private parties

from the United States to fan the flame. At Pembina, on the

border between Rupert's Land and the United States, lived a nest

of desperadoes willing to take any steps to accomplish their

purposes. They had access to all the mails which came from

England to Canada marked "Via Pembina." Pembina was an outpost

refuge for lawbreakers and outcasts from the United States. Its

people used all their power to disturb the peace of Red River

settlement. In addition, a considerable number of Americans had

come to the little village of Winnipeg, now being begun near the

walls of Fort Garry. These men held their private meetings, all

looking to the creation of trouble and the provocation of

feeling that might lead to change of allegiance. Furthermore,

the writer is able to state, on the information of a man high in

the service of Canada, and a man not unknown in Manitoba, that

there was a large sum of money, of which an amount was named as

high as one million dollars, which was available in St. Paul for

the purpose of securing a hold by the Americans on the fertile

plains of Rupert's Land.

Here, then, was an agency of most dangerous proportions, an

element in the village of Winnipeg able to control the election

of the first delegate to the convention, a desperate body of men

on the border, who with Machiavelian persistence fanned the

flame of discontent, and a reserve of power in St. Paul ready to

take advantage of any emergency.'

A still more insidious and threatening influence was at work..

Here again the writer is aware of the gravity of the statement

he is making, but he has evidence of the clearest kind for his

position. A dangerous religious element in the country—

ecclesiastics from old France—who had no love for Britain, no

love for Canada, no love for any country, no love for society,

no love for peace! These plotters were in close association with

the half-breeds, dictated their policy, and freely mingled with

the rebels- One of them was an intimate friend of the loader of

the rebellion, consulted with him in his plans, and exercised a

marked influence on his movements. This same foreign priest,

with Jesuitical cunning, gave close attendance on the sick

Governor, and through his family exercised a constant and

detrimental power upon the only source of authority then in the

land. Furthermore, an Irish student and teacher, with a Fenian

hatred of all things British, was a "familiar" of the leader of

the rebellion, and with true Milesian zeal advanced the cause of

the revolt.

Can a more terrible combination be imagined than this? A

decrepit government with the executive officer sick; a

rebellious and chronically dissatisfied Metis element; a

government at Ottawa far removed by distance, committing with

unvarying regularity blunder after blunder; a greedy and foreign

cabal planning to seize the country, and a secret Jesuitical

plot to keep the Governor from action and to incite the fiery

Metis to revolt!

The drama opens with the appointment, in September, 1869, by the

Dominion Government, of the Hon. William McDougall as

Lieutenant-Governor of the north-west territories, his departure

from Toronto, and his arrival at Pembina, in the Dakota

territory, in the end of October. He was accompanied by his

family, a small staff, and three hundred stand of arms with

ammunition. He had been preceded by the Hon. Joseph Howe, of the

Dominion Government, who visited the Red River settlement

ostensibly to feel the pulse of public opinion, but as

Commissioner gaining little information. Mr. McDougall's

commission as Governor was to take effect after the formal

transfer of the territory. He reached Pembina, where he was

served with a notice not to enter the territory, yet he crossed

the boundary line at Pembina, and took possession of the

Hudson's Bay Fort of West Lynn, two miles north of the boundary.

Meanwhile a storm was brewing along Red River. A young French

half-breed, Louis Riel, son of the excitable miller of the Seine

of whom mention was made—a young man, educated by the Roman

Catholic Bishop Taché, of St. Boniface, for a time, and

afterwards in Montreal, was regarded as the hope of the Metis.

He was a young man of fair ability, but proud, vain, and

assertive, and had the ambition to be a Caesar or Napoleon. He

with his followers had stopped the surveyors in their work, and

threatened to throw off the approaching tyranny. Professing to

be loyal to Britain but hostile to Canada, he succeeded, in

October, in getting a small body of French half-breeds to seize

the main highway at St. Norbert, some nine miles south of Fort

Garry.

The message to Mr. McDougall not to enter the territory was

forwarded by this body, that already considered itself the de

facto government. A Canadian settler at once swore an affidavit

before the officer in charge of Fort Garry that an armed party

of French half-breeds had assembled to oppose the entrance of

the Governor.

Here, then, was the hour of destiny. An outbreak had taken

place, it was illegal to oppose any man entering the country,

not to say a Governor, the fact of revolt was immediately

brought to Fort Garry, and no amount of casuistry or apology can

ever justify Governor McTavish, sick though he was, from

immediately not taking action, and compelling his council to

take action by summoning the law-abiding people to surround him

and repress the revolt. But the government that would allow the

defiance of the law by permitting men to live at liberty who had

broken jail could not be expected to take action. To have done

so would have been to work a miracle.

The rebellion went on apace; two of the so-called Governor's

staff pushed on to the barricade erected at St. Norbert. Captain

Cameron, one of them, with eyeglass in poise, and with affected

authority, gave command, "Remove that blawsted fence," but the

half-breeds were unyielding. The two messengers returned to

Pembina, where they found Mr. McDougall likewise driven back and

across the boundary. Did ever British prestige suffer a more

humiliating blow?

The act of rebellion, usually dangerous, proved in this case a

trivial one, and Kiel's little band of forty or fifty

badly-armed Metis began to grow. The mails were seized, freight

coming into the country became booty, and the experiment of a

rising was successful. In the meantime the authorities of Fort

Garry were inactive. The rumour came that Riel thought of

seizing the fort. An affidavit of the chief of police under the

Government shows that he urged the master of Fort Garry to meet

the danger, and asked authority to call upon a portion of the

special police force sworn in, shortly before, to preserve the

peace. No Governor spoke; no one even closed the fort as a

precaution; its gates stood wide open to friend or foe.

This exhibition of helplessness encouraged the conspirators, and

Riel and one hundred of his followers (November 2nd) unopposed

took possession of the fort and quartered themselves upon the

Company. In the front part of the fort lived the Governor ; he

was now flanked by a bodyguard of rebels ; the master of the

fort, a burly son of Britain, though very gruff and out of

sorts, could do nothing, and the young Napoleon of the Metis

fattened on the best of the land.

Riel now issued a proclamation, calling on the English-speaking

parishes of the settlement to elect twelve representatives to

meet the President and representatives of the French-speaking

population, appointing a meeting for twelve days afterwards.

Mr. McDougall, on hearing of the seizure of the fort, wrote to

Governor McTavish stating that as the Hudson Bay Company was

still the government, action should be taken to disperse the

rebels. A number of loyal inhabitants also petitioned Governor

McTavish to issue his proclamation calling on the rebels to

disperse. The sick and helpless Governor, fourteen days after

the seizure of the fort and twenty-three days after the

affidavit of the rising, issued a tardy proclamation condemning

the rebels and calling upon them to disperse. The Convention met

November 16th, the English parishes having been cajoled into

electing delegates, thinking thus to soothe the troubled land.

After meeting and discussing in hot and useless words the state

of affairs, the Convention adjourned till December 1st, it being

evident, however, that Riel desired to form a provisional

government of which he should be the joy and pride.

The day for the reassembling of the Convention arrived. Riel and

his party insisted on ruling the meeting, and passed a "Bill of

Rights" consisting of fifteen provisions. The English people

refused to accept these propositions, and, after vainly

endeavouring to take steps to meet Mr. McDougall, withdrew to

their homes, ashamed and confounded.

Meanwhile Mr. McDougall was chafing at the strange and

humiliating situation in which he found himself. With his family

and staff poorly housed at Pembina and the severe winter coming

on, he could scarcely be blamed for irritation and discontent.

December 1st was the day on which he expected his commission as

Governor to come into effect, and wonder of wonders, he, a

lawyer, a privy councillor, and an experienced statesman, went

so far on this mere supposition as to issue a proclamation

announcing his appointment as Governor. As a matter of fact, far

away from communication with Ottawa, he was mistaken as to the

transfer. On account of the rise of the rebellion this had not

been made, and Mr. McDougall, in issuing a spurious

proclamation, became a thing of contempt to the insurgents, an

object of pity to the loyalists, and the laughing-stock of the

whole world. His proclamation at the same time authorizing

Colonel Dennis, the Canadian surveyor in Red River settlement,

to raise a force to put down the rebellion, was simply a brutum

fulmen, and was the cause to innocent, well-meaning men of

trouble and loss. Colonel Dennis succeeded in raising a force of

some four hundred men, and would not probably have failed had it

not transpired that the two proclamations were illegal and that

the levies were consequently unauthorized. Such a thing to be

carried out by William McDougall and Colonel Dennis, men of

experience and ability! Surely there could be no greater fiasco!

The Canadian people were now in a state of the greatest

excitement, and the Canadian Government, aware of its blundering

and stupidity, hastened to rectify its mistakes. Commissioners

were sent to negotiate with the various parties in Red River

settlement. These were Vicar-General Thibault, who had spent

long years in the Roman Catholic Missions of the North-West,

Colonel de Salaberry, a French Canadian, and Mr. Donald A.

Smith, the chief officer of the Hudson's Bay Company, then at

Montreal. On the last of these Commissioners, who had been

clothed with very wide powers, lay the chief responsibility, as

will be readily seen.

A number of Canadians—nearly fifty—had been assembled in the

store of Dr. Schultz, at the village of Winnipeg, and, on the

failure of Mr. McDougall's proclamation, were left in a very

awkward condition. With arms in their hands, they were looked

upon by Riel as dangerous, and with promises of freedom and of

the intention of Riel to meet McDougall and settle the whole

matter, they (December 7th) surrendered. Safely in the fort and

in the prison outside the wall, the prisoners were kept by the

truce-breaker, and the Metis contingent celebrated the victory

by numerous potations of rum taken from the Hudson's Bay Company

stores.

Riel now took a step forward in issuing a proclamation, which

has generally been attributed to the crippled postmaster at

Pembina, one of the dangerous foreign clique longing to seize

the settlement. He also hoisted a new flag, with the

fleur-de-lis worked upon it, thus giving evidence of his

disloyalty and impudence. Other acts of injustice, such as

seizing Company funds and interfering with personal liberty,

were committed by him.

On December 27th—a memorable day—Mr. Donald A. Smith arrived.

His commission and papers were left at Pembina, and he went

directly to Fort Garry, where Riel received him. The interview,

given in Mr. Smith's own words, was a remarkable one. Riel

vainly sought to induce the Commissioner to recognize his

government, and yet was afraid to show disrespect to so high and

honoured an officer. For about two months Commissioner Smith

lived at Fort Garry, in a part of the same building as Governor

McTavish.

Mr. Smith says of this period, "The state of matters at this

time was most unsatisfactory and truly humiliating. Upwards of

fifty British subjects were held in close confinement as

political prisoners; security for persons or property there was

none. . . . The leaders of the French half-breeds had declared

their determination to use every effort for the purpose of

annexing the territory to the United States."

Mr. Smith acted with great wisdom and decision. His plan

evidently was to have no formal breach with Riel but gradually

to undermine him, and secure a combination by which he could be

overthrown. Many of the influential men of the settlement called

upon Mr, Smith, and the affairs of the country were discussed.

Riel was restless and at times impertinent, but the Commissioner

exercised his Scottish caution, and bided his time.

At this time a newspaper, called The New Nation, appeared as the

organ of the provisional government. This paper openly advocated

annexation to the United States, thus show the really dangerous

nature of the movement embodied in the rebellion.

During all these months of the rebellion, Bishop Taché, the

influential head of the Roman Catholic Church, had been absent

in Rome at the great Council of that year. One of his most

active priests left behind was Father Lestanc, the prince of

plotters, who has generally been credited with belonging to the

Jesuit Order. Lestanc had sedulously haunted the presence of the

Governor; he was a daring and extreme man, and to him and his

fellow-Frenchman, the cure of St. Norbert, much of Kiel's

obstinacy has been attributed. Commissioner Smith now used his

opportunity to weaken Riel. He offered to send for his

commission to Pembina, if he were allowed to meet the people.

Riel consented to this. The commission was sent for, and Riel

tried to intercept the messenger, but failed to do so. The

meeting took place on January 19th. It was a date of note for

Red River settlement. One thousand people assembled, and as

there was no building capable of holding the people, the meeting

took place in the open air, the temperature being twenty below

zero.

The outcome of this meeting was the election and subsequent

assembling of forty representatives—one half French, the other

half English—to consider the matter of Commissioner Smith's

message. Six days after the open-air meeting the Convention met.

A second "Bill of Rights" was adopted, and it was agreed to send

delegates to Ottawa to meet the Dominion Government. A

provisional government was formed, at the request, it is said,

of Governor McTavish, and Riel gained the height of his ambition

in being made President, while the fledgling Fenian priest,

O'Donoghue, became "Secretary of the Treasury."

The retention of the prisoners in captivity aroused a deep

feeling in the country, and a movement originated in Portage La

Prairie to rescue the unfortunates. This force was joined by

recruits at Kildonan, making up six hundred in all. Awed by this

gathering, Riel released the prisoners, though he was guilty of

an act of deepest treachery in arresting nearly fifty of the

Assiniboine levy as they were returning to their homes. Among

them was Major Boulton, who afterwards narrowly escaped

execution, and who has written an interesting account of the

rebellion.

The failure of the two parties of loyalists, and their easy

capture by Riel, raises the question of the wisdom of these

efforts. No doubt the inspiring motive of these levies was in

many cases true patriotism, and it reflects credit on them as

men of British blood and British pluck, but the management of

both was so unfortunate and so lacking in skill, that one is

disposed, though lamenting their failures, to put these

expeditions down as dictated by the greatest rashness,

The elevation of Riel served to awaken high ambitions. The late

Archbishop Taché, in a later rebellion, characterized Riel as a

remarkable example of inflated ambition, and called his state of

mind that of "megalomania." Riel now became more irritable and

domineering. He seemed also bitter against the English for the

signs of insubordination appearing in all the parishes. The

influence of the violent and dastardly Lestanc was strong upon

him. The anxious President now determined to awe the English,

and condemned for execution a young Irish Canadian prisoner

named Thomas Scott. Commissioner Smith and a number of

influential inhabitants did everything possible to dissuade

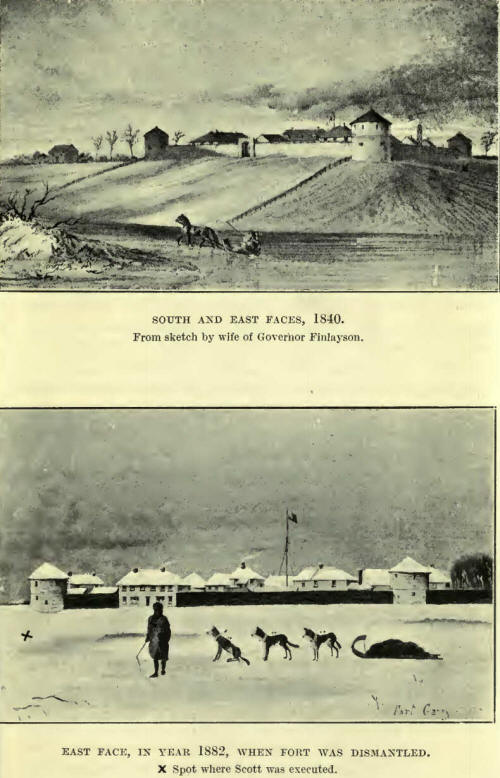

Riel, but he persisted, and Scott was publicly executed near

Fort Garry on March 4th, 1870.

"Whom the gods destroy, they first make mod." The execution of

Scott was the death-knell of Riel's hopes. Canada was roused to

its centre. Determined to have no further communication with

Riel, Commissioner Smith as soon as possible left Fort Garry and

returned to Canada.