Andrew Graham's "Memo."—Prince of Wales

Fort—The garrison— Trade—York Factory—Furs—Albany—Subordinate

forts—Moose —Moses Norton—Cumberland House—Upper

Assiniboine—Rainy Lake—Brandon House—Red River—Conflict of the

Companies.

The new

policy of the Company that for a hundred years had carried on

its operations in Hudson Bay was now to be adopted. As soon as

the plan could be developed, a long line of posts in the

interior would serve to carry on the chief trade, and the forts

and factories on Hudson Bay would become depots for storage and

ports of departure for the Old World.

It is interesting at this point to have a

view of the last days of the old system which had grown up

during the operations of a century. We are fortunate in having

an account of these forts in 1771 given by Andrew Graham, for

many years a factor of the Hudson's Bay Company. This document

is to be found in the Hudson's Bay Company house in London, and

has been hitherto unpublished. The simplicity of description and

curtness of detail gives the account its chief charm.

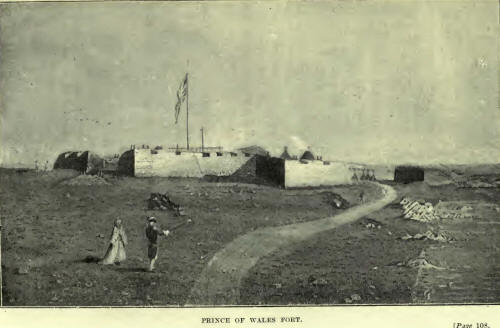

Prince of Wales Fort.—On a peninsula at the

entrance of the Churchill River. Most northern settlement of the

Company. A stone fort, mounting forty-two cannon, from six to

twenty-four pounders. Opposite, on the south side of the river,

Cape Merry Battery, mounting six twenty-four pounders with

lodge-house and powder magazine. The river 1,006 yards wide. A

ship can anchor six miles above the fort. Tides carry salt water

twelve miles up the river. No springs near; drink snow water

nine months of the year. In summer keep three draught horses to

haul water and draw stones to finish building of forts.

Staff:—A chief factor and officers, with

sixty servants and tradesmen. The council, with discretionary

power, consists of chief factor, second factor, surgeon, sloop

and brig masters, and captain of Company's ship when in port.

These answer and sign the general letter, sent yearly to

directors. The others are accountant, trader, steward, armourer,

ship-wright, carpenter, cooper, blacksmith, mason, tailor, and

labourers. These must not trade with natives, under penalties

for so doing. Council mess together, also servants. Called by

bell to duty, work from six to six in summer ; eight to four in

winter. Two watch in winter, three in summer. In emergencies,

tradesmen must work at anything. Killing of partridges the most

pleasant duty.

Company signs

contract with servants for three or five years, with the

remarkable clause: "Company may recall them home at any time

without satisfaction for the remaining time. Contract may be

renewed, if servants or labourers wish, at expiry of term.

Salary advanced forty shillings, if men have behaved well in

first term. The land and sea officers' and tradesmen's salaries

do not vary, but seamen's are raised in time of war."

A ship of 200 tons burden, bearing

provisions, arrives yearly in August or early September. Sails

again in ten days, wind permitting, with cargo and those

returning. Sailors alone get pay when at home.

The annual trade sent home from this fort

is from ten to four thousand made beaver, in furs, felts,

castorum, goose feathers, and quills, and a small quantity of

train oil and whalebone, part of which they receive from the

Eskimos, and the rest from the white whale fishery. A black

whale fishery is in hand, but it shows no progress.

York Factory.—On the north bank of Hayes

River, three miles from the entrance. Famous River Nelson, three

miles north, makes the land between an island. Well-built fort

of wood, log on log. Four bastions with sheds between, and a

breastwork with twelve small carriage guns. Good class of

quarters, with double row of strong palisades. On the bank's

edge, before the fort, is a half-moon battery, of turf and

earth, with fifteen cannon, nine-pounders. Two miles below the

fort, same side, is a battery of ten twelve-pounders, with

lodge-house and powder magazine. These two batteries command the

river, but the shoals and sand-banks across the mouth defend us

more. No ship comes higher than five miles below the fort.

Governed like Prince of Wales Fort.

Complement of men : forty-two. The natives come down Nelson

River to trade. If weather calm, they paddle round the point. If

not, they carry their furs across. This fort sends home from

7,000 to 33,000 made beaver in furs, &c, and a small quantity of

white whale oil.

Severn Fort.—On

the north bank of Severn River. Well-built square house, with

four bastions. Men: eighteen. Commanded by a factor and sloop

master. Eight small cannon and other warlike stores. Sloop

carries furs in the fall to York Factory and delivers them to

the ship, with the books and papers, receiving supply of trading

goods, provisions, and stores. Severn full of shoals and sand

banks. Sloop has difficulty in getting in and out. Has to wait

spring tides inside the point. Trade sent home, 5,000 to 6,600

made beaver in furs, &c.

Albany

Fort.—On south bank of Albany River, four miles from the

entrance. Large well-built wood fort. Four bastions with shed

between. Cannon and warlike stores. Men: thirty; factor and

officers. River difficult. Ship rides five leagues out and is

loaded and unloaded by large sloop. Trade, including two

sub-houses of East Main and Henley, from 10,000 to 12,000 made

beaver, &c. (This fort was the first Europeans had in Hudson

Bay, and is where Hudson traded with natives.)

Henley House.—One hundred miles up the

river from Albany. Eleven men, governed by master. First founded

to prevent encroachments of the French, when masters of Canada,

and present to check the English.

East Main House.—Entrance of Slude River. Small square house.

Sloop master and eleven men. Trade: 1000 to 2000 made beaver in

furs, &c. Depth of water just admits sloop.

Moose Factory.—South bank of Moose River,

near entrance. Well-built wood fort—cannon and warlike stores.

Twenty-five men. Factor and officers. River admits ship to good

harbour, below fort. Trade, 3,000 to 4,000 made beavers in furs,

&c. One ship supplies this fort, along with Albany and

sub-forts.

These are the present

Hudson's Bay Company's settlements in the Bay. "All under one

discipline, and excepting the sub-houses, each factor receives a

commission to act for benefit of Company, without being

answerable to any person or persons in the Bay, more than to

consult for good of Company in emergencies and to supply one

another with trading goods, &c, if capable, the receiver giving

credit for the same."

The movement

to the interior was begun from the Prince of Wales Fort up the

Churchill River. Next year, after his return from the discovery

of the Coppermine, Samuel Hearne undertook the aggressive work

of going to meet the Indians, now threatened from the

Saskatchewan by the seductive influences of the Messrs.

Frobisher, of the Montreal fur traders. The Governor at Prince

of Wales Fort, for a good many years, had been Moses Norton. He

was really an Indian born at the fort, who had received some

education during a nine years' residence in England. Of

uncultivated manners, and leading far from a pure life, he was

yet a man of considerable force, with a power to command and the

ability to ingratiate himself with the Indians. He was possessed

of undoubted energy, and no doubt to his advice is very much due

the movement to leave the forts in the Bay and penetrate to the

interior of the country. In December of the very year (1773) in

which Hearne went on his trading expedition inland, Norton died.

In the following year, as we have seen,

Hearne erected Cumberland House, only five hundred yards from

Frobisher's new post on Sturgeon Lake. It was the intention of

the Hudson's Bay Company also to make an effort to control the

trade to the south of Lake Winnipeg. Hastily called away after

building Cumberland House, Hearne was compelled to leave a

colleague, Mr. Cockings, in charge of the newly-erected fort,

and returned to the bay to take charge of Prince of Wales Fort,

the post left vacant by the death of Governor Norton.

The Hudson's Bay Company, now regularly

embarked in the inland trade, undertook to push their posts to

different parts of the country, especially to the portion of the

fur country in the direction from which the Montreal traders

approached it. The English traders, as we learn from Umfreville,

who was certainly not prejudiced in their favour, had the

advantage of a higher reputation in character and trade among

the Indians than had their Canadian opponents. From their

greater nearness to northern waters, the old Company could reach

a point in the Saskatchewan with their goods nearly a month

earlier in the spring than their Montreal rivals were able to

do. We find that in 1790 the Hudson's Bay Company crossed south

from the northern waters and erected a trading post at the mouth

of the Swan River, near Lake Winnipegoosis. This they soon

deserted and built a fort on the upper waters of the Assiniboine

River, a few miles above the present Hudson's Bay Company post

of Fort Pelly.

A period of

surprising energy was now seen in the English Company's affairs.

"Carrying the war into Africa," they in the same year met their

antagonists in the heart of their own territory, by building a

trading post on Rainy Lake and another in the neighbouring Red

Lake district, now included in North-Eastern Minnesota. Having

seized the chief points southward, the aroused Company, in the

next year (1791), pushed north-westward from Cumberland House

and built an establishment at Ile à la Crosse, well up toward

Lake Athabasca.

Crossing from Lake

Winnipeg in early spring to the head waters of the Assiniboine

River, the spring brigade of the Hudson's Bay Company quite

outdid their rivals, and in 1794 built the historic Brandon

House, at a very important point on the Assiniboine River. This

post was for upwards of twenty years a chief Hudson's Bay

Company centre until it was burnt. On the grassy bank of the

Assiniboine, the writer some years ago found the remains of the

old fort, and from the well-preserved character of the sod, was

able to make out the line of the palisades, the exact size of

all the buildings, and thus to obtain the ground plan.

Brandon House was on the south side of the

Assiniboine, about seventeen miles below the present city of

Brandon, Its remains are situated on the homestead of Mr. George

Mair, a Canadian settler from Beauharnois, Quebec, who settled

here on July 20th, 1879. The site was well chosen at a bend of

the river, having the Assiniboine in front of it on the east and

partially so also on the north. The front of the palisade faced

to the east, and midway in the wall was a gate ten feet wide,

with inside of it a look-out tower (guérite) seven feet square.

On the south side was the long store-house. In the centre had

stood a building said by some to have been the blacksmith's

shop. Along the north wall were the buildings for residences and

other purposes. The remains of other forts, belonging to rival

companies, are not far away, but of these we shall speak again.

The same activity continued to exist in

the following year, for in points so far apart as the Upper

Saskatchewan and Lake Winnipeg new forts were built. The former

of these was Edmonton House, built on the north branch of the

Saskatchewan. The fort erected on Lake Winnipeg was probably

that at the mouth of the Winnipeg River, near where Fort

Alexander now stands.

In 1796,

another post was begun on the Assiniboine River, not unlikely

near the old site of Fort de la Reine, while in the following

year, as a half-way house to Edmonton on the Saskatchewan,

Carlton House was erected. The Red River proper was taken

possession of by the Company in 1799. Alexander Henry, junr.,

tells us that very near the boundary line (49 degrees N.) on the

east side of the Red River, there were in 1800 the remains of a

fort.

Such was the condition of

things, so far as the Hudson's Bay Company was concerned, at the

end of the century.

In twenty-five

years they had extended their trade from Edmonton House, near

the Rockies, as far as Rainy Lake; they had made Cumberland

House the centre of their operations in the interior, and had

taken a strong hold of the fertile region on the Red and

Assiniboine Rivers, of which to-day the city of Winnipeg is the

centre.

Undoubtedly the severe

competition between the Montreal merchants and the Hudson's Bay

Company greatly diminished the profits of both. According to

Umfreville, the Hudson's Bay Company business was conducted much

more economically than that of the merchants of Montreal. The

Company upon the Bay chiefly employed men obtained in the Orkney

Islands, who were a steady, plodding, and reliable class. The

employes of the Montreal merchants were a wild, free, reckless

people, much addicted to drink, and consequently less to be

depended upon.

The same writer

states that the competition between the two rival bodies of

traders resulted badly for the Indians. He says: "So that the

Canadians from Canada and the Europeans from Hudson Bay met

together, not at all to the ulterior advantage of the natives,

who by this means became degenerated and debauched, through the

excessive use of spirituous liquors imported by these rivals in

commerce."

One thing at any rate

had been clearly demonstrated, that the inglorious sleeping by

the side of the Bay, charged by Dobbs and others against the old

Company, had been overcome, and that the first quarter of the

second century of the history of the Hudson's Bay Company showed

that the Company's motto, "Pro Pelle Cutem," "Skin for Skin,"

had not been inappropriately chosen.