|

FROM the time of the

Reformation at least, some attention had been given to the youth of

Coldstone, but the first teacher of whom I have any knowledge is one of

whom I know nothing, not even his name, except that, for taking part in

the rebellion of 1715, he was deprived of his position and never more

returned thereto.

Really the first teacher

of the parish of whom I know anything is Francis Beattie. He was a

native of what was known as "The Braes O' Cromar," situated immediately

under the shadow of Morven and Culblean, which should by right have

belonged to the parish of Coldstone, but for some reason or rather

unreason, had been attached to the parish of Glenmuick whose church was

about eight miles distant, and consequently seldom, if ever attended.

In that section, so

orphaned of the church, the father of Francis Beattie lived as tenant of

a little farm. He seems to have been a rather eccentric character,

priding himself upon three accomplishments. He is quoted as saying of

himself, "There are three things I'm sair maister o,' girding coags,

ca'in oxen i' the pleuch an' singin' The Psalms o' Dauvid." Coags by the

way were cooperage vessels about half the size of common pails with one

stave projecting upwards for a handle, used for milking cows. It was

understood that at one time he cherished the laudable ambition of being

able to turn to good account, and probably with pecuniary advantage, his

qualification last named, by becoming church precentor in the Coldstone

kirk and that while so minded he would embrace any opportunity of

displaying his fitness for that important office. A Sunday morning at

last came when such an opportunity seemed to present itself. The

Minister was promptly on hand, and so was David, but no precentor had

put in an appearance. Thinking that the service was being unnecessarily

delayed, David, from his seat in the church called out, "Proceed, Sir,

I'm here." Whether his services were accepted or not I have not heard,

but I have no reason to believe that his worthy aspiration to a

permanent seat in the ''lectern" was ever realized.

FRANCIS BEATTIE

His son Francis was born

on the first day of January 1785 As a young man he was considered an

athlete, but at or near the end of his college career, he walked home

from Aberdeen on a warrn day. Arriving at the mineral wells of Poldhu,

after a walk of nearly forty miles, he stopped for a drink, and a swim

in the mill dam nearby. From that indiscretion, as was currently

believed, resulted an attack of paralysis which deprived him completely

and permanently of the use of both his lower limbs.

Soon after that

misfortune he obtained from the presbytery of Kincardine O'Neal,

appointment as school-master of the Coldstone school. The Presbytery

might well have hesitated to risk in such a position a candidate so

cruelly handicapped. In a country so poor as Cromar then was, with few

fences for the protection of growing crops, many children were early

withdrawn from school for herding cattle and such other services. This

made necessary the return to school for successive winters of a large

number of boys who would sometimes attain to man's estate before a

reasonable grounding in "three r's" was reached, which was the worthy

ambition for their children cherished by most of the parents in the

locality. Most of the boys as they grew older became studious and well

improved their belated opportunity of education. But one boy or more old

enough to know better was generally in attendance whose presence and

evil example might menace the order and discipline of a master who had

to be carried daily into and out of the school-room, and was incapable

of rising from the seat in which he was placed. The confidence of the

presbytery, however, was not misplaced for probably in no school in the

country was better order maintained.

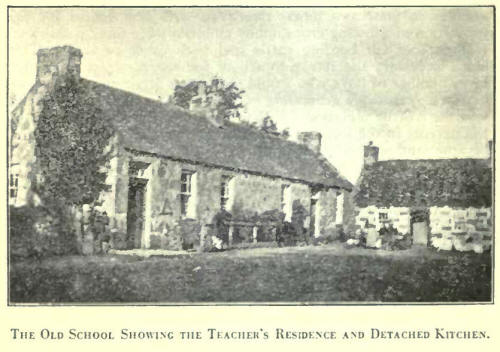

THE SCHOOL ROOM

I am unable to give the dimensions of the

school-house in which he commenced his work, nor can I give the date of

its erection. It was an oblong, rectangular structure 50 or 60 by 30 or

35 feet. Its longer walls ran north and south, and the building faced

the east, the playground being in front and extending southerly some

eighty feet or so along what had at one time been a public road. In the

front wall were two good sized windows, and the door was at the

south-easterly angle. Within the outer door was a small vestibule, then

an inner door opened on an aisle paved with Hag-stones, which ran

northward to an open area about twelve feet wide which extended along

the northerly wall from front to rear of the room. The teacher's desk

occupied the north-westerly angle, while at the north-east was a door to

the Teacher's residence, which wan attached to the school. At the middle

of the north end, was the fire-place innocent of grate or device other

than a bare hearth for fuel or fire. Parallel with the front wall was

one long bench (perhaps two) fronted by a continuous desk from

vestibule, almost to the fire-place. In front of this desk ran a seat

without a desk in front. This seat, running as it did along the

flagstone paved aisle, and directly under the eve of the "maister," with

no desk intervening to give shelter from that orb perpetually on the

outlook for evil-doers and "triflers," was wonderfully suited for

observation, and in it were therefore seated the lazy, the mischievous

and the idlers. For that reason it was known as "the trifler's seat."

Across the aisle, seats were at right angles, from door to fireplace.

Some time after the

school was built, but whether before or after Mr.

Beattie became teacher, I do not know, a wing was added to the west

side, about 25 feet square. In it the seats were ranked north and south,

divided by a central aisle running east and west which communicated with

the open space in front of the master's desk.

The whole school area as thus in full view from the

teacher's seat which was elevated about 30 inches above the floor. On

his left hand was the open fire-place. On his right, within the new

section, was a space left for fuel. Extending across the front of the

fire-place was a long moveable bench for the use of pupils who might

require in cold weather to warm up. On this "the rnaister"

rested his feet, his seat being extended beyond the desk, toward the

fire, for his accommodation.

The children's desks were fairly comfortable and

convenient for writing purposes, but the benches were rigidly attached

to the floor and entirely separate from the desk. I do not remember any

trouble at any stage of my physical development from maladjustment of

the seat, but there was no rest for the back, the space behind being too

great for the use of the desk in the rear for that purpose.

From the granite obelisk erected to his memory in the

Cold-stone churchyard "By his grateful and attached pupils, who mourn in

him a zealous teacher, a wise counsellor and a constant friend," it

appears that Mr. Beattie was born as has been stated, on January 1st

1785, and died 24th Sept. 1855, and that he had taught in the same

parish for 49 years. He must therefore have commenced his duties in

1806; when twenty-one years of age.

In Mr. Beattie's day, although a meagre salary was

paid to parish school-masters from national funds therefor provided,

each pupil was required to pay school fees for tuition. In addition to

these there was the burden of providing fuel for the winter which pupils

might discharge at their Option either by a trifling monetary payment

quarterly, or by bringing to the school each day a peat. turf or piece

of wood. Few, if any, paid in coin, so each morning might be seen boys

and girls gathering from all directions toward the school, each having

under his arm a peat or its combustible equivalent to be carried past

the master's desk and duly deposited in the appointed place. From this

duty there was no escape. The stem ruler of the little kingdom, seated

on his throne long ahead of the appointed owning hour, and before the

unlocking of the door, scanned with eagle eye each entering pupil, and

saw that the required contribution was made.

Some time early in Mr. Beattie's career as teacher,

an unfounded Suspicion is said to have arisen that the fuel so provided

was being dishonestly converted to use in the teacher's residence. In

order that proof of such conversion might be secured, some miscreant,

probably inspired by someone older than himself, conceived the idea of

making a hole in a peat, filling it with gun-powder, plugging the hole

and placing this peat in the fuel-bin. Some time afterward, on a Cold

winter day. when the bench in front of the fire was crowded with pupils

who had come up to warm, the explosion occurred, and whether from its

force or from the fright thereby produced, those on the bench were

thrown backward to the floor, but fortunately no harm resulted. Soon

after the explosion came a history lesson with the story of The Gun

powder plot, when the teacher sententiously remarked "We also had our

Gunpowder Plot."

THE CATECHISM.

Only one other incident from times before my own

comes to mind. It relates to John Farquharson of Cairnmore, a distant

relative of my own, who in youth does not seem to have shown any special

aptitude or inclination for study. On a Saturday morning John had duly

reported at school for the regular Saturday half-day drill in the

shorter catechism, then, and for some years after Mr. Beattie's death,

maintained weekly except on holidays, under legal obligation. From

attendance none were exempt, unless the parents had conscientious

objections. The smaller children who could read were required to

memorize, and come weekly prepared to recite one fresh question. When in

that way the whole catechism had been gone through, the pupil was

advanced into what was known as "the repetition class," which embraced

all the pupils except the very little ones. This class, especially in

the winter, was very large and the line commencing at the fire-place and

thence extending along the east wall, to and around the vestibule and

along the south wall sometimes overflowed into the rear of the cross

benches parallelling the south wall. In this class one half of the whole

catechsim was gone through every Saturday, and the other half the

Saturday next succeeding, and so on from week to week interminably

holidays only excepted. No enquiry was made as to the pupil's

understanding of the question or its answer, but woe betide the pupil

who should fail in his recitation!

Presumably John had been on his first journey through

the book, though he may have been in the repetition class, for those who

came into the advanced class insufficiently grounded, were liable to

have a hard time, as no one could know beforehand what question it might

be his lot to answer. Whatever his class, John in due course got his

question and made a brave attempt to recite the words of the proper

answer, but the teacher had to come to his aid. It was soon found that

ordinary coaching was of no avail. "Vain is the priming of the pump when

the cistern is dry." Either to ascertain the amount of work which the

pupil had put on his task or to make an exhibition of him before the

class, the teacher proceeded to lead him deliberately off the track.

"Gold and silver are precious things" said the prompter. "Gold and

silver are precious things," repeated the pupil. "Correction is a hard

thing," proceeded the teacher. "Correction is a hard thing," assented

John. "But," said the teacher, producing the strap, "you must come up

here and get some of it."

A DOMINE OF THE OLD SCHOOL

During his early years, Mr. Beattie had a high

reputation as teacher and advanced pupils came from a distance to board

with him or in the neighbourhood, to attend his school for the study of

Greek, Latin and mathematics in preparation for entry into the college

in Aberdeen (or rather one of them, for Aberdeen then, as some one

wittily remarked, like England had two universities).

He ruled his little kingdom with method, perfect

order and not a little severity. At a certain minute every morning the

great man was carried to his seat. Carefully his big watch was held in

hand, and a previously selected and special trumpeter stood outside

awaiting the signal. At the instant when ten o'clock was indicated, the

signal was given and immediately a great blast of the horn announced to

the pupils that the hour of commencement had arrived, and the country

people around were enabled to set their clocks accordingly.

Nor was it a matter of small importance in a district

isolated as Coldstone was from telegraph and railway station, to be

afforded a means of time adjustment so cheap and so efficient. That the

time so announced should be perfectly correct, the teacher took the

utmost pains every day when the sun was bright enough to cast a shadow,

he stationed one of the larger boys at a south window a few minutes

before twelve o'clock noon, as ascertained by his watch, to observe the

shadow on the window sill which would be then nearing a line which, at a

certain day of the year, it would strike precisely at noon. As soon as

that line was reached, the boy gave the signal, "It's at it." To the

time thus indicated, the teacher's watch was immediately adjusted,

subject, however, to correction as ascertained from a table indicating

the variation of solar from true Greenwich time in each day throughout

the calendar year. Not only was school time thus rendered exactly

correct, but the Sunday church bell was regulated by his instruction

also.

In my father's day there do not appear to have been

in use, in Mr. Beattie's school at least, any beginner's books to lead

the pupil on from letters through simple letter-combinations to little

words, and graduating thence onward to literary efficiency. The little

tots had then their first lessons from the book of Proverbs. From the

pedigogical standpoint that certainly was not the approved method for

the imparting of literary instruction, though possibly the early

acquaintance with that wonderful book of wisdom thus, to some extent,

naturally acquired, may have had its influence in the production of that

saneness which is sometimes alleged to distinguish the people of

Scottish origin as a class.

However that may be before my day the hook of

Proverbs had ceased to be used as a text-book as distinct from any other

part of the sacred volume. Indeed, as a matter of fact, I never had a

lesson from that particular book in the public school Primer and graded

lessons, perhaps not inferior in many respects to those now in use in

Canada, greeted my first appearance at school in 1851. The new series,

however, had one great defect; they had no pictures or illustrations of

any kind. That deficiency is made the more glaring, and more significant

by the fact that no pupil, big or 'little, could, without incurring

punishment make any attempt at drawing of any kind, whether on slate or

paper. It would almost seem that the early reformers, in revolt from the

pictures and images used in the worship of the Roman churches looked

with suspicion, as indeed almost a violation of the second commandment,

upon the drawing or making of any picture or representation of anything

material or otherwise in earth or heaven, for any purpose. Whatever the

reason, the suppression of all picture-making in school was absolute. No

pictures adorned the walls, no flowers were ever seen in school, and in

the whole curriculum there was nothing for the cultivation of the

aesthetic sense.

It may be of interest to note that every scholar

attending Mr. Beattie's school commenced writing exercises with a quill,

which was mended and trimmed every morning as needed by the teacher

himself. When the exercise was finished the pupil was required to

present his copy book for the master's inspection. That done, with

approval or otherwise, he would take from a box kept tinder the master's

desk, a handful of fine sand, and holding his copybook slantingly over

the box, would pour the sand over the still damp ink, the sand adhering

to it acting like blotting-paper. As soon as dry the adhering sand was

brushed off and the Iines stood forth as fresh and clear as if

blotting-paper had been used.

In his own peculiar way "the Maister" was kind to his

scholars. During the long summer days (and holidays were not given until

September) he allowed two hours for recess, that is from noon until two

o'clock and it was understood that he preferred that none should go home

for dinner. The children were invited to leave their lunches in his

kitchen, which was a building separate from his residence. Thither, with

whoop and yell they speeded as soon as released at noon, to snatch their

lunches, and hastily squatting on the green sward, or under the

beautiful larches, enjoy as only healthy children can, their frugal

meal. On wet days they were allowed the run of the kitchen with all its

accommodation, downstairs and up, as well as on the rickety stair

between. In this hospitality he was nobly seconded by his faithful

house-keeper, Bell Taylor who was not less eager than himself to see to

their comfort and entertainment.

In my day, it was not necessary to get a reminder on

a hot day in July or August that "the burn" was a good place of refuge

from the heat, nor to have assurance that it would do us no harm, on

such a day to stay under till school should be called. The burn's

effects in that direction we had all tested to our own satisfaction, for

in it had we not waded, fished, bathed and tried to swim, first

succeeding in our endeavour last mentioned in water shallow enough to

permit of manual contact with the ground. It was not therefore simply

the information that the mercurial column was seeking relief from the

sweltering heat in the shade of the eightieth degree, and that the burn

was a good place, that we appreciated. It was the fact of our teacher

talking to us from his gig as he sometimes would do, as we were seated

at dinner, or as we amused ourselves on the play-ground on a hot day,

that we appreciated. Such familiarity showed that he was interested in

us and was concerning himself for our comfort and enjoyment. Perhaps our

thoughts did not so embody themselves at the time, but the unexpressed

glow of appreciation with which our hearts responded to the master's

condescension meant all that I have tried to put in words, and more.

Not less pleasing to me is the memory of an annual

feast of goose-berries, when all the scholars were made free to help

themselves from his garden. My impression of him from all the personal

experience, and evidence otherwise at command, is that he had a kind

heart, though that aspect was not often in evidence, or manifest to his

pupils generally.

Mention has already been made of a bench that was

stretched along in front of the fire-place for the accommodation of

pupils on cold days, and incidentally for the accommodation of the

master's pedal extremities. It had also uses less pleasant, if not less

important. To the leg of the master's desk next this bench he had

attached a strong cord with which he would lasso the more inveterate of

the "tritlers," as he called the idlers. Its noose was large enough to

receive a boy's head, and was always ready for use. Triflers by habit

and repute were placed more immediately under the task-master's eye.

along the "trifler's seat," which it will be rernembered was peculiarly

suited for such a purpose. Contrary to the rule of other royal courts it

was personages least in favour who had the privilege of special nearness

to this sovereign. So, in the inverse order of goodness and

acceptability, they were Strung along the seat from the far off end to

the front. At any one time there were not many in the line, but whether

many or few each was conscious of being under constant observation, and

of the possibility of the special distinction of an invitation to a seat

on the bench at the feet of the august personage, at whose command he

must himself put his head in the loop.

Of the stem days of a century or more earlier when

the great lords had the power of pit and gallow's the story is told of a

man who, under such authority, was condemned to be hanged. The victim

had serious, perhaps conscientious, objections to the carrying out of

the sentence, and in defending himself as best he could was giving the

executioner much unnecessary trouble. His wife, perceiving her husband's

unreasonableness, called out to him, "Pit your head i' the mink, John,

an' no anger the guid laird!"

When good Mr. Beattie gave a like order, the first

impulse was always to refuse and resist, but superior force, or second

thoughts, invariably led to compliance, and in went the reluctant head.

Pilloried thus in the presence of his fellows who were not always

sympathetic, the culprit's position might be supposed to be one of

shame, but I question much if that was the prevailing feeling or emotion

of the person most directly interested. There was however, one

satisfaction: so long as the victim was content to sit in quietness and

attend to his book there would be no immediate inconvenience. Even the

bonds of moral obliquity which are so readily accepted seem no

inconvenience so long as the captive accepts their servitude and yields

to the strain. But the moment he realizes his bondage and makes an

effort for release, he finds to his dismay that he is held captive by

the cords of his own sin, with which by his own hands he had bound

himself.

The boy was captive after all less by the master's

cord than by his own fatal habit of self-indulgence and sluggishness,

the abandonment of which would procure for him instant release. That

abandonment, however, was not easy. His disinclination for work, so long

yielded to, made application to his book irksome and disagreeable. His

spasmodic attempts at industry as a temporary expedient to avoid

consequences still more serious, would soon become intolerable. The

habit of idling would assert itself again, and immediately that terrible

strap that knew neither mercy nor vacation, but which, by fiery ordeal

indurated or as its owner, around Christmas would express it

"sweetened," to highest efficiency would descend suddenly and

unannounced on the head of the hapless "trifler." Of course, he tried to

avoid it, but Nemesis is obdurate. The cord that his own hand had put

upon his neck Prevented his feeble attempt to "jouk," and lie had

Perforce to take the full number of his stripes.

I know all about it, for I held, for some time, with

Geordie Clark of Millahole, the first or second place on the trifler's

seat, and had the doubtful distinction more than once of putting around

my own neck the cord of shame, and of hearing as I did so, "He's a handy

horse that harnesses himself."

Many a queer story could that bench tell. One day

which I well remember, Willie Gauld of the Milton went up to the bench

to warm. The teacher was either more cross than usual, or he may, have

had some reason to suspect that Willie was pretending. However that may

have been, Willie was called to the desk to justify his presence before

the fire. His hands were found to be warm, and there was therefore a

prima facie case against the suspect. Poor Willie pleaded that his feet

were cold. All in vain. Promptly came the order, "Take off your shoes

and stockings." The condition of the feet gave no confirmation of

Willie's statement, though the court decided that that condition might

be somewhat improved by percussion. So poor Willie was ordered to stand

up on the Innich on his bare feet, in which position he was compelled to

dance a natural, if not an elegant step to the music of the swift

descending strap.

One day which I remember well, some boys were

detected observing very interestedly something outside, to the neglect,

no doubt, of their proper work. To each of the offenders, the teacher

assigned ironically some duty, which I presume was appropriate to a

military camp in regular warfare. Who the others were, or to what duties

each had been assigned I have no recollection, but I remember that to

Rob Kellas was assigned the duty of looking out for the enemy. Who or

what "the enemv" was, I did not know, but I had heard at Sunday School

of the arch-enemy, and realized that to Rob had been committed a most

solemn responsibility.

This Kellas, by the way, acquired at school the

nick-name of "Stot" (or steer), a name, whether appropriate or not, that

stuck to him to the end of his school days. Rob, and a number of his

fellows had been trespassing in Mr. Beattie's little turnip field, in

which the plants at the time were so very small that considerable

destruction could well be wrought by a hand of greedy youngsters out for

spoil. Mr. Beattie called up the offenders, and in the presence of the

school administered a scathing rebuke, all of which, I have quite

forgotten except that addressed to Kellas. "And you. Rob Kellas, I am

told that you were eating like a stot." That was quite enough.

Inevitably he was thenceforth known as "The Stot."

In his efforts to rule his little kingdom Mr. Beattie

resorted to some methods perhaps not quite justifiable, pretending to

have eyes in the back of his head and a sort of qualified omniscience.

By the position of the body, he could see when the little hands were

engaged with something under the desk. Immediately the stern command

would come. "Jock Pledger, come up here." The little offender would

immediately comply, surprised at ability to see through the desk or

other obstruction. I have used John Fletcher's name, though I cannot

recall a single instance in which he was found a transgressor. "Jock

Pledger," or sometimes "Jock Jessamine" were the names by which he was

wont to be addressed. The occasional use of the mother's name for one of

his pupils toward the end of his forty nine years in the one School

showed that the successive generations that had passed under his rod

were beginning to claim a present place in the chambers of the teacher's

mind.

Sometimes, looking over his spectacles, or with

spectacles tilted on his bald head, in which attitude, I seem to see him

now, Mr. Beattie would peer with eagle eye through the little railing

that fringed the front of his desk, and addressing some idler by name,

would make some exclamation such as "Geordie Clark, you are trifling

willingly and wittingly." This would be followed by an invitation to the

front and the usual finger strapping, palm down on top of the desk.

Occasionally a boy would come to school with long

hair, ill combed and hanging over his eyes. For this offence there was

neither reproof uttered nor punishment of the ordinary kind

administered. He was simply ordered to appear at the desk. To such an

invitation a pupil, conscious as most were of failure of duty or of

positive wrong-doing on other counts, would give an apprehensive and

reluctant response. No sooner had the touselled head appeared at the

desk than out from the desk's interior came a pair of scissors, and with

a single movement, a swath was cut sufficient to clear the eyes, and

also to make sure that the boy would return next day with hair properly,

if not elegantly, trimmed.

It is generally understood that the average boy, in

his early teens at least, is a good deal of a savage. If so, there was

not much in that school to encourage appreciation of the beautiful or

the fine. The ideal of the school-yard was strength, courage and force,

all good, but anything of fineness or beauty was more or less held in

contempt. Trampling on the weak was of course discouraged, and bigger

boys saw that no tyranny was exercised by the strong over the weak. A

fight, however, on what was deemed equal terms, was always rather

welcomed by the average boy. Indeed some went so far as to say that the

master, himself, who had an eagle eye for any bully, and was quick to

find means to cut short any unequal fight, was slow to notice, and had

seldom, if ever been known to pretend to see or interfere with, a fight

between equals.

Among the girls in my day, my sister Betty, Lizzie

Stewart of Newkirk, and all the Elizabeths, were supposed to be special

favourites with their teacher on account of bearing the name of his

deceased wife, for whom his affection seems to have been sincere and

profound. It was said that during her life-time she would come into the

school at the sound of any special trouble and crave mercy for the

offender. Her interposition, it was said, was never resented, and her

plea never denied. Their one son and only child went to the bad through

intemperance. Though possessed of ability that would have made him a

useful man, he ultimately became incapable of earning his own living or

of being in any way a help to his neighbours. His father settled on him

an annuity, on which after his father's death he lived, with a family

near Ballater. He was found after a debauch, dead at the back of a stone

dyke. Thus passed out poor Frank, no one poorer by his passing, nor

enobled by his career.

On one occasion, however, I was saved a whipping by

the intervention of that same kind-hearted, erring Frank. In the

forenoon, I had got a whipping, which for me was not an uncommon

experience. In obedience to the stern command which none might

disregard, I had put my hand on the master's desk, palm down and with

fingers extended. The master, then grasping my wrist with his left hand

to prevent withdrawal, brought down with his right upon my vise-held

digits several strokes of the great instalment of his authority,

delivered with his wonted energy. The business end of the strap (or

"handle" as my brother James called it on one occasion when, as a little

boy, he remonstrated with the master, and excused himself for not coming

up for discipline when called, on the ground that the teacher used,

improperly, the handle instead of the lash of his whip), was composed of

two pieces of ordinary shoe-leather laid one on top of the other and

sewed together at the upper end. These pieces were perhaps half or three

quarters of an inch in width and both split upwards probably five

inches, thus forming four equal tails. In manufacture great care had

been taken to round off all sharp angles and make the whole surface

smooth and sleek to avoid the possibility of cuticle abrasion. Attached

to these was a flexible leather strap doubled to form a loop for

convenient and effective handling. That was the part which my brother

had taken for the lash. On returning to my seat, I noticed that one of

my fingers was bleeding. To this I paid little attention, but one of the

bigger girls noticed it and told Mr. Beattie.

Soon a messenger from the teacher found me fishing or

"guddling in the burn" in blissful forgetfulness of the woes of the

morning. These were, however, soon recalled when the messenger announced

that my presence was required at the master's desk. On my appearance I

was asked to show my hand. After examination, he asked how it had got

hurt. I replied that he himself had done it. That he said was not true,

and that if I should persist in saying so, he would have to punish me

for telling a lie. Strap in hand, he gave me opportunity to retract my

statement and waited for my reply. It was a position to me entirely new,

and I was in terrible straits. Had the situation been prolonged, I am

afraid that I should not have been able to demonstrate that in me

existed the materials of which the martyrs are made. Indeed I think I

was on the point of yielding when in came Mr. Frank, who asked his

father to let me go, with the result that I was freed. I am unwilling to

believe that Mr. Beattie was actuated by fear for his own reputation. My

impression is rather that he was anxious to satisfy himself that he had

not been guilty of drawing blood in the exercise of discipline. As a

matter of fact I do not think that I mentioned the incident at home at

all, nor did it appear to me at the time a matter of much importance.

That was the only time that I remember when Mr.

Beattie did anything of doubtful honour, and even then his conduct

however unwise, is capable of a favourable construction. His penalties

were often severe, sometimes injudicious, and occasionally, for great

offences, administered in a manner indecent and wholly objectionable.

That he was up to the best ideals and methods of his day I have no

doubt, and by these only should he be judged. In the winter school among

lads corning of age some were sure to be troublesome. Two young men, I

particularly remember had to be expelled under circumstances, and with

manifestations of obscenity and abuse on retiring, which indicate real

depravity. Such things must he taken into account in estimating what was

reasonable severity, especially in the case of a man handicapped

physically as was poor Mr. Beattie.

DEBITS AND CREDITS OF THE OLD SYSTEM

His failure in my case was not that he whipped me,

though if that was a duty it was certainly not left undischarged, but

that he failed to arouse in me any interest whatever in what he sought

to teach. He practically never asked a question about a lesson and

seldom gave a word of instruction about anything—not even as to the

meaning of the words in a reading lesson, further than to require the

class to memorize the list of words with meanings attached appended to

each lesson in the reader. These lists I memorized for the most part to

the satisfaction of the teacher without realizing that the explanation

given had any reference to the word explained. It is to be hoped that I

was the only one so stupid, but as no information was given to the class

as to the purpose of such a list, or of a dictionary, I imagine that

there were others not receiving much more benefit than myself.

At the age of nine, when Mr. Beattie died, I could

read and write fairly well, could work out slowly sums in addition,

subtraction, multiplication and more slowly still in division. I could

also repeat with some difficulty the grammer rules in the Junior

text-book then in use, which I had memorized without understanding, or

caring to understand, a single word. With still more facility I could

repeat the shorter Catechism from end to end, as well as several of the

paraphrases of which two verses had to be memorized weekly for

recitation on Monday, in proof of proper Sunday observance. That much I

had to the credit of four years of dawdling, but had the first two been

cut out, I feel quite sure that I should have been farther ahead, and

with powers of concentration more fully developed and that my rate of

progress to the end of school days, if not to the end of life's last

chapter, should have been accelerated.

Once I was guilty of a

childish prank which seemed to shock Mr. Beattie's sense of propriety,

and called forth words which, for the first time in my experience,

expressed regret. With some appearance of feeling, he said he had not

thought me capable of doing a thing like that. For the first time it

came to my consciousness that he had any confidence in me, or any care

for me personally. I remember yet the bitterness of my regret that I

should have done anything to occasion the withdrawal of his regard. My

impression is that if he had directed his appeal more to the reason and

still more to the affection of his pupils, and less to dread of

punishment, discipline would have been more easily maintained, his

influence on his pupils immensely increased, his own charade improved,

his disposition sweetened and his professional success more pronounced.

His physical condition was unfortunately a constant reminder of his

helplessness, and no doubt all his mental faculties were directed

abnormally toward the maintenance of his own authority with an intensity

that disturbed the equilibrium of his better nature.

As already noted, my father quitted the tailor trade

about the year 1830 and went to help his father on his little farm of

Tillymutton. Soon after his arrival there he joined a night class which

Mr. Beattie had started for the purpose of helping any young fellows

whose early education had been neglected to a knowledge of at least

arithmetic. There can be no doubt that the ears of both teacher and

taught would be given to all information available regarding the newly

invented locomotive and the railroad on which it was said to run. No one

in the whole district had ever seen a locomotive or a railway. Father

used to tell that the first railway in Scotland was a short line from

Dundee in Newtyle. That, I believe was one of the first, though I

understand not quite the first. However, an opportunity was soon

unexpectedly given my father to make a visit to Dundee and there see for

himself what at the time he believed, was the only railway to to be seen

in Scotland. A relative was about to take up residence m Dundee and

Grandfather despatched him, with a horse and cart, to move the

belongings. This was a mission in all respects after my father's own

heart. No one ever enjoyed more than he, an opportunity of doing a

kindness, and few of his time and class had a deeper interest in any new

improvements being introduced. So he started on his journey, full of the

thought of the railway its locomotive and its cars, in Dundee alone in

all the North Scotland to be seen.

On reaching his destination, he hastily disposed of

horse and cart and started off alone on foot for the railway station

which he found without difficulty. The railway was minutely examined,

the construction of the rails duly noted, and last and greatest wonder

of all, the locomotive came in for closest scrutiny. At last, fully

satisfied, he started for his temporary home, but suddenly became

bewildered and did not know which way to go. In his haste to be off to

the station he had neglected to take note of the name of the street or

the number of the house into which as a stranger his friend had come.

For a time he could think of no means of finding his way except by

recourse to the public crier, a functionary who still in those days for

a fee, Would traverse the streets announcing lost articles. Soon,

however, he recovered his bearings and his trouble was an at end.

On his return home many were interested in his story,

and none were more so than his friend Mr. Beattie who questioned him

most particularly as to what kept the wheels on the rails, and as to

what gave the driving wheels their tractive power, and was much

surprised to learn that the wheels and rails were without cogs, that the

tractive potency of the wheels was derived solely from friction, and

that one flange on the wheels kept them on the rails.

One story I must not omit. James Stewart of

Tomulachie, whom, in recent years, we have all known as "Old Uncle," had

given offence in some way of which I know nothing. The outcome was a

suit in court in which Mr. Beattie was the pursuer, or plaintiff. What

the verdict was, I never heard, nor is it pertinent to my story, but the

effect was strained relations between the school-house and Tomulachie.

The two principals to the action would meet for some time thereafter

with mutually averted faces. After a time Mr. Beattie began to soften

sornewhat, and in his gig, happening to meet his recent antagonist on

foot, on a rainy day, ventured to break the long silence by saluting his

still irate neighbour with, "It's a rainy day, James." To this

Tomulachie, probably as pleased as "the maister" to have an end to the

unpleasantness, could not refrain from one last good shot, so made the

laconic reply "Ye micht gie't a summons man!" Unpromising as at the time

this attempt at reconciliation may have seemed, I have no doubt that it

resulted in an honourable and lasting peace.

In taking leave of Mr. Beattie, I must in fairness

allow him a word spoken some time before his death to my father in

criticism of myself. His verdict was, "Donald is a boy of a good

disposition, but a very trifling; boy." That I am sure was the most

lenient criticism that truth would then permit, and I

would that its concluding part had less application, in truth, today.

I have taken the liberty of describing my school and

my first schoolmaster, and of showing and perhaps criticizing, the

methods of that day. I could not well do otherwise, for a historical

record demands a true picture. But I trust that what can be said has

been said in extenuation, and "nought set down in malice." What pains

there may have been at the time from rapped fingers or injured feelings

have long since passed away, and mellow recollection paints the old

school of Coldstone, even under Mr. Beattie, suffused in kindly light.

It is not easy for one even of my generation, to

estimate truly the character and usefulness of this, in many respects,

remarkable man. All of my father's generation entertained for him ever

the highest respect and even veneration. It would be manifestly unfair

to judge him, either as man or teacher, by standards of today which are

so different from those of that remote yesterday, receding so fast from

the vision and ideals of the present time.

The long term of forty-nine years in one school came

at last to a close. Some day about the end of August 1855, he dismissed

us for the last time. In doing so he said that those of us old enough to

understand must have noticed his failing health and strength, and now he

had to tell us that it was very unlikely he should be able to meet us

again in his accustomed place. Probably he said a few words more that I

have forgotten—of the pleasure that he had in his long tenure of office

as teacher of youth, but certainly no word of sell-pity escaped his

lips. He had bravely done his duty, according to his light and in full

accord with the highest ideals of his day. and his final departure was

not long delayed. The end came on the fourth of September of the same

year.

His successor was Mr. John Grant Michie.

MR MICHIE AND A NEW ERA

With the advent of Mr. Michie in the autumn of 1855 a

new era dawned for the school of Logie Coldstone. He was a native of the

parish of Crathie, his ancestral home overlooking the river Dee from the

northern side, almost opposite the castle of Balmoral. He was a young

man just through with his arts course in Marischall College, Aberdeen,

and commenced his new duties with all the enthusiasm of youth and of

earnest purpose. All the old books and ancient methods were immediately

discarded. The primative method of fuel supply was abandoned, and a

regular system of registering daily the respective standings, at the

closing hour each day of the six pupils at or nearest the top in each

class was introduced. This register and its record, became a matter of

deepest interest, for upon its testimony depended the awarding of three

prizes for as many members of each class, shown to have at an appointed

day the highest aggregate of marks. Examination tests, entirely new to

the school, were introduced, and among the pupils extraordinary

enthusiasm became immediately manifest.

Some laughable incidents come to my mind, of which to

me at any rate, not the least interesting was a question put to the

Bible Class as to what was meant by unleavened bread. Down the class

that question went till it reached the foot. There stood, for the first

time, Charlie Thompson from the farm known as "The Glack," drawn to the

school by the rising fame of the new teacher. Whether or not Charlie

himself had a clear idea as to what distinguished unleavened from other

bread I do not know, but he called out in instant and eager response, "sauty

bannocks." As these bannocks were known to be produced without any

fermenting process and were therefore unleavened, this answer was

accepted, and Charlie marched proudly to the top. Charlie was a pupil

thenceforth to be reckoned with until his final leaving for the

university in Aberdeen, but from that first incident to the time of his

final leaving he was known as "Sauty Bannocks."

Mr. Michie continued to hold the position of teacher

in Coldstone until some time after 1873, leaving at last to become

minister of a parish church by the Dee, five or six miles distant from

the Coldstone school-house. To him, perhaps, more than to any other man,

apart from my own father, I owe, the strongest influence that went to

the formation and moulding of character in some of the most

impressionable years of my life. His friendship and unvarying kindness

were maintained by him, and enjoyed by me, to the end of his life which

was reached in the early years of the present century.

During his pastorate, he found time to write a

history of the parish of Logie-Coldstone which he loved so well. From

his pen had come, before that time, his Deeside Tales and his history of

Loch Kinord. The late Sir Robertson Nicol remarked in a sketch of a tour

made by him through that locality "In the grave of Mr. Michie, lies

buried much of the history of this part of the country." |