ABERNETHY has for ages been famous for

its pine-forests. The remains of great trees in our

mosses, and the blocks, sometimes three, one on the top of

the other, found in improving land, tell of the glory of

the past, and so far as is known, though there have been

changes, there has been no break in the continuity from

the most ancient times. Long ago, the lower parts of our

parish seem to have been swamps and morasses, the haunt of

wild beasts, and the home of savage desolation, while the

higher grounds on the slopes of the hills were occupied by

the people. The hut circles and the marks of furrows on

the moors show this. It is now nearly the reverse. The

lower grounds are cultivated, while the higher have been

given up to wild animals and to sheep. About the year

1760, we find Sir Ludovick Grant greatly concerned as to

the state of the woods. In an advertisement by himself,

and his eldest son James, yr. of Grant, to their tenants,

he says that the woods are of great value, and that their

destruction would be of the greatest loss to him, and to

his vassals and tenants, "yet within the last half

century, through the malice and negligence of evil-minded

and thoughtless people. the best and greatest part of said

woods have been destroyed and rendered useless both to

Heritors and Tenants" by burning of heather and otherwise.

To prevent such practices, it was intimated that they (he

and his son) "were determined to put in execution the

several salutary laws made against stealing, cutting, and

destroying woods, and raising of Muir-burns; and likewise

against the Destroyers of Deer, Roes, and Black-Cock, and

other game within their Estates." The advertisement then

gives warning that any person found guilty of the crimes

set forth would be duly punished, and it is significantly

added, the said person shall also forfeit any favour that

they might otherwise have expected of the said Family."

This may refer to promises of land and such like for

service rendered. The Baron-bailies were required to send

in lists of persons convicted. New Foresters were also

appointed, and strict instructions given to them. "Whereas

the very greatest abuses of every kind for many years have

been committed in all my Woods of Strathspey, by stealing,

cutting, barking, and otherwise destroying them to such a

degree that if some effectual remedies are not provided

against such villanous practices in time coming, they must

all be soon ruined," and for these reasons they were

enjoined to take all due measures to protect the property

that was being so wantonly and wickedly destroyed. These

measures seem to have been so far successful, but it was

many years before the evils complained of were thoroughly

stopped. In 1819, the Woods and Wood Manufactures on the

Grant Estates were placed under the charge of the late Mr

William Forsyth, The Dell, and by his management,

extending over twenty years, great improvements were

effected, and large annual profits secured.

Roads have been made passing through

the woods in various directions. There are also walks and

cross-paths on Craigmore amid the Torr. It is easy,

therefore, not only to saunter about at one’s own sweet

will, but to walk or drive for miles and miles through the

vast wilderness of woods. What will be seen depends mainly

on the seer. Some complain of the dulness and want of

life, but to the ‘ quiet eye" there is always a rich

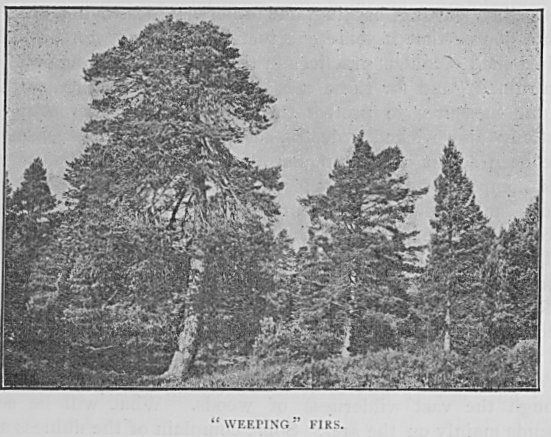

harvest." Sometimes a tree may be observed, standing out

from the others, eminent for its size and height, or

remarkable for some other peculiarity. A little beyond the

Dell gate, near the Moss, there is a tree called "The

Queen." It is a splendid specimen of the ancient pine.

About a mile further on to the right there are two or

three trees of an unusual kind. The normal habit of the

fir is to grow up straight and stiff, but these have the

droop and bend of veritable "weepers." Another "fairlie"

is the variegated fir, so called from the golden tinge of

the needles or leaves. Of this rare kind there are some

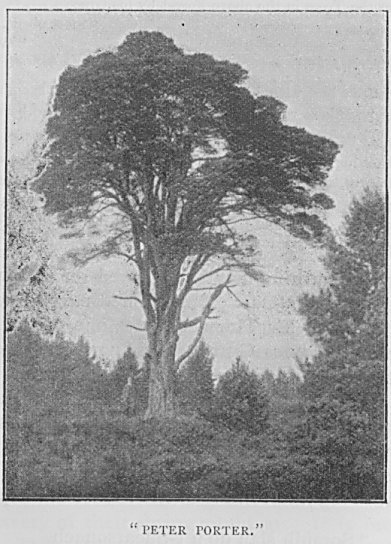

specimens in the forest. The biggest trees remaining are

to be found at Carn Chnuic, Sleighich, and Craigmore. One

of these in the last named locality bears the name of

"Peter Porter."

The Grants at the port or ferry of

Balliefurth were called "porters," and it is said that one

of them of the name of Peter

had taken a contract to cut down a certain number of trees

on Craigmore, but that when he came to tackle with this

giant of the wild, he shrunk from the task. It would not

pay. So the tree stands to this day, bearing his name, and

an object of admiration to hundreds of visitors from year

to year. It is 80 feet in height, 14 feet in girth, with

huge branches and wide spreading cable-like roots, and

must be about 300 years old. Perhaps the largest fir of

which we have record was that called ‘‘Maighdean Coire—chungiaich,’’

at Baddan-bhuic, in Glenmore. The following

notice is taken from the Journal of Forestry and Estate

Management for September, 1877 :—-

Through the kind interest which Sir

Robert Christison, Bart., takes in all things

arboricultural, the public have now an opportunity of

seeing, in the National Industrial Museum of Science and

Art in Edinburgh, a curious relic of the ancient forest of

Glenmore, and of judging of the quality and valuable

properties of the native Scots fir timber. At the request

of Sir Robert, the Duke of Richmond and Gordon has sent

for exhibition in the Museum a plank of Scots fir, 5

feet 7 inches wide at the bottom, which was presented

in 1806 to the then Duke by the person who purchased and

cut down the whole of Glenmore forest. It bears its rather

curious history on a brass plate affixed to its face, of

which the following is a verbatim and literal copy : —

"In the year 1783 William Osborne,

Esq., merchant, of Hull, purchased of the Duke of Gordon

the Forest of Glenmore, the whole of which he cut down in

the space 22 years, and built during that time at the

mouth of the River Spey, where never Vessel was built

before, 47 Sail of Ships of upwards of 19,000 Tons

burthen. The largest of them, of 1050 Tons, and three

others but little inferior in size, are now in the service

of his Majesty and the Honble. East India Company. This

Undertaking was compleated at the expense (for Labour

only) of above 70,000£.

To his Grace the Duke of Gordon this

Plank is offered as a Specimen of the Growth of one of the

Trees in the above Forest by his Grace’s

"most obedt, Servt.

"W. Osbourne.

"Hull, Sepr 26th, 1806."

Sir Robert Christison has, with his

usual accurate criticism, examined the plank, and reports

to us as follows regarding the tree from which it had been

taken:-

"The tree must have been 11 feet in

girth at the bottom of the plank, and 16 at top, 6 feet 3

inches higher up. I can make out 243 layers on one radius;

seven are wanting in the centre, and seven years at least

must be added for the growth of the tree to the place of

measurement. Hence the tree must have been about 260 years

old. The outer layers on this radius are so wide that it

must have been growing at a goodly rate when it was cut

down."

The marks of burning may be observed on

the bark of some of the oldest trees. Great fires

sometimes broke out, from accident or malice. Mr Thomas

Baylis, one of the York Company, wrote to Sir James Grant,

12th August, 1731, complaining of a fire that had been

maliciously raised to the east of Balnagown, and which had

been very destructive. He says that not only had the

Company lost much wood, but that it cost them "43 bottles

Ferrintosh and 39 of Brandie," given to the men who were

employed in stopping the conflagration. It is probably

this fire that is referred to in a Gaelic rhyme of the

period.

Soraidh slan do’n t—Shearsonach

Chuir teas ri Culnacoille,

S’ dh’ fuadaich mach na Sasanaich

A dh’ firiaraidh ‘n leasach bheurla,’’

i.e., "Hail to the forester, who

set heat about Coulnakyle and drove out the Sassenachs, to

seek the better English." Rev. Lachlan Shaw mentions

another great fire that occurred in 1746. The tradition as

to this fire is, that a certain smith who had his forge at

the verge of the forest was complaining one day of the

trouble he had with horses that went astray in the dense

woods. A Lochaher man who heard him said, "Make me a

good dirk, and I’ll take in hand to save you from such

trouble." He agreed. Next day the forest was in a

blaze, and a wide clearance was soon made. The Cameron

disappeared for a twelvemonth, but then he came quietly

and claimed his dirk. This gave the name Tomghobhain,

i.e., Smith Hill, to the place. Another great fire is

referred to by Sir Walter Scott (Letter to Lord Montagu,

23rd June, 1822), when the Laird of Grant is said to have

sent out the Fiery Cross for help. Five hundred men

assembled, "who could only stop the conflagration

by cutting a gap of 500 yards in width betwixt the burning

wood and the rest of the forest. This occurred about 1770,

and must have been a tremendous scene."

The woods are on the whole marked by

lonesomeness, but now and again signs of animal life

appear. Perhaps a robin pops out from a juniper bush, as

if claiming acquaintance; or a squirrel crosses the path

and nimbly climbs some fir tree near, from which it looks

down upon you with mild surprise; or a startled roebuck

bounds into the thicket, and you watch with delight its

graceful movements, and perhaps remember the beautiful

promise, "The lame man shall leap as an hart." In winter

red deer may often be seen singly, or in groups quietly

feeding in the glades. Black game are numerous, and

sometimes the rare and singular sight may be obtained, as

at the grass parks at Rhiduack, of the cocks strutting and

fuming, with tails erect, in all the bravery of their

spring plumage. It is interesting to watch them. They not

only strut like turkeys, but they prance and leap in a

sort of dance, and with a curious cluck, and have sharp

fightings for supremacy. Black game do not pair like

others of the grouse species. There is an old pipe tune

which refers to this curious custom, "Ruidhle na

Coilich dhubh, ‘s dannsa na tunnagan, air an tulaich laimh

ruinn"—the reels of the black-cocks, and the dancing

of the ducks on the sunny knolls near by. Sometimes on a

winter day or in early spring, on the outskirts of the

forest, or where the birches and firs intermingle, you may

come upon a company of tits feeding. It is a pretty sight.

The tits are fond of society. Generally several kinds go

together. There may be the common " blue," and the rarer

long-tailed," and the still rarer "crested," and along

with them creepers and golden wrens. They have their

different habits and ways. One perhaps carefully scans a

stump, another clings with tenacity to a twig, while

others are perched about in all sorts of attitudes, some

near the top of a tree, others swinging on the branches,

and others again hanging on in some wonderful way to the

bending sprays, but all seeking their food with patient

care. They make the air lively with their twittering and

their brisk activities. But if you stand and watch, you

will soon lose sight of them. Having tried one tree, they

are off to another, and so they pass on, seeking pastures

new. Perhaps a creeper that has been paying special

attention to a decaying birch, winding round and round,

and stopping here and there for tit-bits, seems left

behind. But no. He sees that he is alone, and quickly

rejoins his friends. What a sweet picture of ompanionship!

What a delightful lesson of cheerful content and industry!

"The birds around me hopp’d and

play’d,

Their thoughts I cannot measure;

But the least motion that they made,

It seemed a thrill of pleasure.

If this belief from heaven be sent,

If such be nature’s plan,

Have I not reason to lament

What man has made of man."— Wordsworth.

In the pine forests in our northern

climate there is a marked difference between one season

and another. Visitors who roam the woods in summer speak

with rapture of the play of light, the rich colouring, and

the sweetness of the scented air, but let them come back

in winter or spring, and they will find a woful change. No

doubt the woods, even in time of snow, have their charms

but they are then more picturesque than salubrious, and

when the thaw comes, and the air is dank and cold, and

when passing through you get a bath that chills you to the

marrow, it will perhaps be realised that the woods are not

always a safe and pleasant haunt, that they can breed

colds, catarrhs, and rheumatisms, as well as throw out

sweet scents and healing odours.