|

We come now to treat of a

period which produced changes on every burgh in Scotland, but more

especially on those burghs which were the seats of Episcopal dignitaries, we

mean the Reformation in 1560. The Earl of Argyle, who was then the most

popular and most potent nobleman in Scotland, had the influence to introduce

into the see of Brechin Alexander Campbell, a son of the family of

Ardkinglass, who, at the period of his induction in 1566, appears to have

been a mere youth; for we find that, the year after his induction, he got

liberty from Queen Mary to go abroad for his education ; and in the Book of

Assumptions of 28th January 1573-4, it is noticed that he was then at Geneva

at the schools. As there are no documents with Campbell’s name existing in

Brechin from 1569 to 1579, we are inclined to suppose that he had been

abroad between these periods; and we adopt this opinion the more readily,

because we find that, although his licence to go abroad for seven years was

granted in 1567, he was present with Regent Moray in the convention at Perth

in July 1569. During the absence of the bishop for the period alluded to,

David, archdean of Brechin, commendator of Dryburgh, managed the

temporalities, of the bishoprick of Brechin. Alexander Campbell, as we have

said, was inducted into the see in 1566, and he died bishop of Brechin in

1610, so that he filled the Episcopal chairfor forty-four years, from which

circumstance, independent of other authorities, it might fairly be inferred

that he was not a very old man when he was elevated to the dignity of a

bishop. But the most remarkable circumstance connected with this gentleman,

was the terms of the grant in his favour of

the bishoprick. By this document Campbell was empowered to sell, for his own

benefit, all the revenues and properties belonging to the see then vacant,

or when they should become vacant. Of this power the young bishop availed

himself, or was obliged to avail himself, by making large grants to his

patron the Earl of Argyle, who was not without strong temporal reasons for

supporting the Reformation. At the period of Campbells accession, the see of

Brechin was possessed of a revenue of £410 in money, 11 bolls of wheat, 200l

chalder 5 bolls of bere, 123 chalder 3 bolls meal, 15 bolls of oats, 11 and

a half dozen of capons, 16 dozen and ten poultry, 18 geese, and 9 barrels of

salmon annually. But although Argyle swept off the greater part of these

good things, Bishop Campbell made some grants and sales for his own especial

benefit. Thus, immediately on his accession, he dispones the Little Mill of

Brechin, with the acre of land and other rights thereto pertaining, to

William Kinloch, burgess of Dundee, and Janet Lindsay his wife, in liferent,

and to Alexander Ramsay in fee, and that for payment of a price o£ £30, and

an annual feu of 3s. 4d. The property thus sold passed from Ramsay to

William Fullarton of Ardo, who transferred it to the town of Brechin in

1605; and by that corporation the Little Mill was converted into a

waulkmillin 1693, and afterwards disannulled, the Muckle Mill having

swallowed up the duties and properties of the Little Mill. However, if thi&was

then the practice of the Church, it is but justice to say that there were

also many grants made by the Crown of Church property for the promotion of

education at this time. Thus in 1575, according to the records of the Privy

Seal, printed by Mr Chalmers, the teinds of Bonny-ton, not exceeding £20,

which had previously belonged to the canons of the Cathedral, are given.to

James Small, son of George Small, saddler in Edinburgh, who “ being puire,

fathirless, and destitut of all support of parentis or frendis, is of

convenient aige to entir in the studie of grammer, and apt and disposit

thairfore, and promist to be subject to discipline/’ and the master of the

Grammar School of Edinburgh is ordered to receive Small under his charge for

seven years, and thereafter to report that another may be appointed to the

scholarship; and we

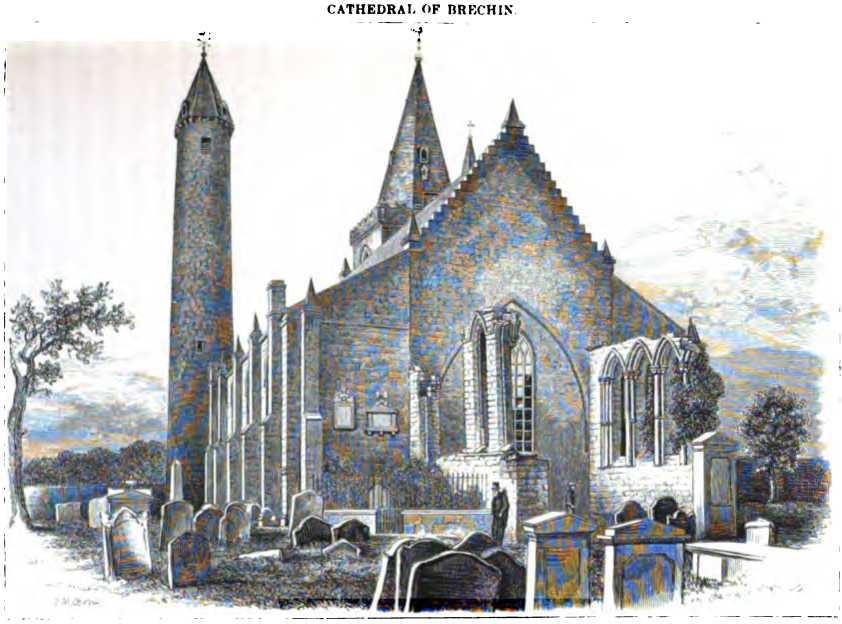

VIEW FROM THE SOUTH-EAST.

observe, accordingly, that

this grant was renewed in 1581 for other seven years, after which these

teinds were gifted for a similar purpose to Henry Sinclair, son of the

deceased Henry Sinclair, writer. A similar gift is made in 1576 of the

emoluments of Kilmoir to James Cokbume “brother-german to Johnne Cokburne

of Clerkingtoun,” who might have been fatherless, but certainly had not been

poor. There are many other grants of a similar kind, but we shall only

further notice that of the teinds of Middle Drums in 1577 to “ Mr John

Nicolsoun, who has been brought up at the schools since his youth, and has

completed his course of philosophy, and intends to pass beyond sea for his

further exercise in good learning, so that he may return again a more

profitable member to serve in this commonwealth.”

The family of Erskine appear

now, as at other times, to have got their share of Church property; thus,

James Erskine, vicar of Falkirk, on 14th March 1585, obtained a grant for

his life of all the annual rents which had been bestowed on the officials “for celebrating of messis, singing and saying of dirigie, and doing of

utheris ryteis, ceremonies, and papisticall services, whilk now be the Word

of God, and laws of his Hienes realm, •are damnit and altuterlie abolischit,”

and for which grant Mr Erskine was to pay yearly to the collector of the

alms for the poor within the city £6, 13s. 4d. Scots. And John Erskine of

Dun, for his “lang, emest, and faithful travellis,” “in the suppressing of superstitioun, papistrie, and idolatrie, and avance-ment and propagatioun of

the evangell of Christ Jesus, the tyme of the reformatioun of the religion,

and in ydnt and faithful per-suerance in the samin,” has a grant for his

lifetime, on 5th November 1587, of various sums from the abbeys of Arbroath

and Cowper, from Jedburgh and Bestennet, the bishoprick of Brechin, and

other places; and this grant is renewed in 1589 to John Erskine of Logy,

grandson of Dun, for the lifetime of Logy.

Bishop Campbell married an

Helen Clepan or Clephan, and of course was the first bishop of Brechin who

had a lawful wife. George Wishart of Drymine, by a charter dated at

Findowrie 23d March 1583, conveys to Mr and Mrs Campbell that estate, so

they appear to have trafficked in Church lands to some account.

James VI., after the Act of

Annexation of the bishops’ temporalities to the Crown, granted those of

Brechin to Campbell in 1588 for his lifetime, for payment of 40 merks Scots

to the Crown; and this grant seems to have been renewed and ratified in

Parliament in 1597, for Campbell makes his right good against the Kings

collector-general by a Decree of Council and Session, dated 1st Feb. 1603.

The example of spoliation set

by the highest dignitary of the church of Brechin was quickly followed by

the smaller powers. The archdean sold his mansion; the presbyters

constituted by the Palatine of Strathearn disposed of their house; the

chancellor conveyed away his manse, and every one was more active than

another in converting the property of the church to his own private use. It

is amusing to notice the various pretexts fallen upon by these churchmen for

this general spoliation. The bishop found that the piece of ground from

nearly opposite the tolbooth to the present Bishops Close had, for many

years, been a receptacle of filth and nuisance, so that not only the

citizens of Brechin had contracted disease and infirmity thereby, but the

bishop himself had not been able to walk in his own garden in safety by

reason thereof, and therefore, being anxious to remove this nuisance, (so

the charter bears,) the bishop and chapter sold the property to James

Graham. The archdean, again, discovered that his mansion was in a ruinous

state, and having of purpose to build a new one in lieu thereof, he sold the

old, with the houses and yards pertaining thereto, for a certain sum of

money, to Mr Thomas Ramsay, commissary of Brechin. The chancellor, in like

manner, conveyed a piece of waste ground upon which formerly stood his

manse, with the garden thereof, to Mr Paul Fraser: and the presbyters of

Strathearn found that part of their residence and habitation was in a like

dangerous and decayed situation, and that there was no cure but a sale.

These and other similar grants are all ratified by James VI.; and thus a

great part of the property belonging to the church of Brechin passed to lay

hands. If we are to believe the reformed clergy of this era, the manses,

houses, and hospitals of the Roman Catholics had been contrived to last only

during the continuance of the papistical dominion; for, at the period

alluded to, the buildings are all found ruinous, while the lands, formerly

so fair, are declared to be pieces of mere waste ground. But there is one

redeeming fact connected with this exhibition of worldly-mindedness—not,

however, emanating from churchmen, but again from the Crown. James VI., by a

charter dated at Leith, 20th June 1572, and granted with consent of John

Earl of Morton, regent, instituted the hospital of Brechin. The charter

narrates that His Majesty, in consideration of the duty incumbent upon him

to provide for the comfort of the poor, the lame, and the miserable, orphans

and destitute persons, grants that there be an hospital founded within the

city of Brechin, into which persons of the above description shall be

admitted and properly accommodated; and because of there having been diverse

annual rents within the city, which, in former times of ignorance, were

mortified to presbyters and chaplains for the performance of masses and

anniversaries, therefore the king appropriates these annual rents to the

more useful purpose of supporting the poor in an hospital, and appoints the

bailies, council, and community of the city of Brechin, and their

successors, to be patrons of the hospital, and ordains that all the lands

and annual rents appropriated for papistical purposes, shall pertain to the

bailies, council, and community for support of the hospital. The chanter's

manse, a house in the Lower Wynd—now called Church Street—was bought for an

hospital in 1608; and in 1688, there is a minute of council strictly

prohibiting any person from receiving any benefit from the hospital except

they “ keep the house and wear the habit; ” but what that habit wa8 we have

not been able to discover. This injunction seems soon to have fallen into

abeyance, for, in 1689, we find a minute of council dispensing with the

pensioners living in the hospital, there called the Bede House, upon account

that it was then neither wind nor water-tight, but continuing to them their

pensions notwithstanding. The revenues thus gifted by King James have always

been applied by the town council of Brechip for the maintenance of poor

people within the town; in 1864 they amounted to £51, 5s., besides £66

obtained for entries from vassals; and twenty-two pensioners had £51, 10s.

divided amongst them; the property being estimated at £1456. The gift was ratified by James

upon his attaining majority in July 1587. The original grant in 1572 is

witnessed by “ Mr George Buchanan, pensioner of Corsragwell,” then keeper of

the Privy Seal, the celebrated historian, and the tutor of James VI.

The Hammermen Incorporation

are possessed of a thick octavo volume, which contains the minutes or scroll

minutes of the Bailie Court of Brechin for 1579-80. The subsequent part of

the book is filled up with the minutes of the incorporation, some of which

indeed, of a comparatively late date, 1770, are intermixed with those of the

acts of the bailies. The only explanation of the matter is that the Messrs

Spense of those periods were, at the same time, the town clerks and trades’

clerks, and that paper being then an expensive article, the book which had

ceased to be used for the Bailie Court was found handy for the hammermen

trade when it was constituted into a corporation in 1600. Be that as it may,

the book is anterior to any in possession of the town council, and contains

some entries worth extracting, as indicating the state of society and the

price of articles towards the close of the sixteenth century. Thus several

parties are punished for using unlawful measures; breaches of the peace are

as numerous as at present, and offenders are punished by fines just as in

the present day. John Hutton is ordained to pay Richard Thomson 30s. for the

hire of a mare for seven days; David Watson claims £3 of Thomas Liddle for

his fee for three half-years, service; decrees are given for the prices of

malt at 5 merks and 6 merks, and at £3 the boll; for 13s. 4d. as the price

of a hide; for 18s. and 40 pence for 100 calf skins and a dozen of kid

skins; for 30 pence for a leg of mutton; and for £4 as the price of 4 ells

of gray cloth. One decree is against John Thomson for 40s. resting of £8 due

James Watt for sybees, that grew in his yard—rather a large quantity of the

onion species 1 John Hamilton and James Strachan apprehended with flesh,

wool, and other property in their possession, are banished the town, and if

found therein afterwards are to be hanged without process; and William

Skinner, for stealing leather meets with a similar sentence. But the bailies

are not always so bloodthirsty; for in the action at the instance of Thomas

Bellie, cutler, against George Meldrum, a burgess of Crail, they postpone giving sentence for a month,

in hopes of the parties agreeing. Query, Had the magistrates doubted their

authority over the Crail burgess? The Muckle Mill and weigh-house are

exposed for let in a way continued down to a much later period, the rouping

being from day to day, and the lease for one year only. In January 1580,

however, the Muckle Mill is agreed to be let for 100 merks of grassum, and

£50 of yearly rent, for nineteen years, to defray the great expenses

incurred at law and by taxation; but this plan having failed, the mill is

let in May for one year, and part of the profit ordered to be given towards

building a school; and Alexander Knox then becomes tenant at 103 merks. Mr

Andrew Leitch, in Nov. 1580,—who, we believe, was the schoolmaster of the

period,—agrees to serve the council for 40 merks yearly, notwithstanding of

their first agreement for 50 merks, and that during their pleasure—not a

very comfortable position for a man of letters. About the same time the

bailies appoint William Thornton, procurator in Dundee, to be their

procurator before the sheriff of Forfar, and grant him a yearly salary of £5

to attend to their lawsuits. In the same year John Schewen, baker, is

admitted freeman, paying 20s. for “spice and wine as accords; ” and in

subsequent minutes it is ordered that no unfreeman bake within burgh, and

that no baker, although a freeman, shall bake any bread under the size

formerly directed, while a committee is appointed for proving the butcher

meat. In May 1580 the bishop and council order a contribution of 100 merks

to be applied for the repairs of the tolbooth, and 80 merks for the repair

of the church; but an obstreperous councillor, David Dempster, in a few days

after, has the hardihood to enter a protest against the order for the repair

of the church, to the no small annoyance, no doubt, of Bishop Alexander

Campbell. But the mighty affair seems to have been in June 1580, when the

great man of the time, and the principal proprietor in the neighbourhood,

John Earl of Mar, Lord of Garioch and Erskine, and proprietor of the

lordship of Brechin and Navar, makes his appearance. On 4th March 1579, the

whole inhabitants had been ordered to meet in the churchyard in array of war

by six o’clock next morning, to proceed with the bailies in affairs of the

city; but in June 1580 all actions, civil and criminal, are put off for some

days; all persons named in a list are ordained to compear well mounted, and

in their best apparel, on two hours’ warning, to meet the King's Grace,

while the Earl of Mar and his servant Thomas Windygates are made burgesses.

The order for the assemblage of the citizens is on 21st June; the admission

of the Earl of Mar, and the adjournment of the Bailie Court, are on 28th

June; so we infer his Kings Grace, the sapient James VI. of Scotland and I.

of England, had been in Brechin on that day, although we have no record of

the event.

Disputes and battling amongst

the noblemen were frequent during the unhappy reign of the beautiful, the

learned, the unfortunate, the ill-treated, but we fear the highly culpable,

Queen Mary; and raids in the neighbourhood of Brechin, involving the peace

of that and other burghs, too frequently occurred. The burgh records of

Arbroath have this entry under date “4th March 1568-9," (that is, March 1569

according to our mode of beginning the year in January):—“ The qlk day, for

divers causes concerning the common weill and relief of the taxation fra the

rayd of Breichin, it is concludit and decernit be the bayleis and counsall

that the haill common gress be devydit and partit, and set to every man,

puir and rich, that plesses to tak part of it: ” and again in June 1572, “

Thir persons are chosyng to ride with my lord, (the abbot, we presume,) to

the raid of Breichin—John Akman, James Pekyman, Wm. Bardy, Andro Dunlop,

James Ramsay, Nyniane Halis; and all the rest of the honest men of the town

oblisit tham to ryid thair tym about when requirit, or ony of the said

persons war chargit thereto in time to coma" There is in the register of the

Privy Seal a remission to John Cockbum, citizen of Brechin, of the crime of

being art and part with Adam Gordon, brother of George Gordon, Earl of

Huntly, and others, in seizing, in August 1570, the “ pyramidis ” of the

steeple of Brechin—the Round Tower, we presume—and maintaining it against

the peace of the king during one of the raids of that unhappy time.

In 1573 a rencontre took

place between the supporters of James and the Earl of Morton, then regent,

and the friends of Queen Mary. This engagement is known by the title of the

“Bourd of Brechin,” and was fought by the Adam Gordon of Auchindown just

named, the brother of Lord Huntly, for the queen’s party, and by the Earl of

Brechin for the regent. In the previous year Gordon had gained a

considerable advantage over his opponents at Craibstane in Aberdeenshire,

and, emboldened by that victory, he entered Angusshire. The regent’s party

resolved to stop Gordon, and for this purpose they assembled all the forces

of Angus at Brechin. But Gordon, being apprised of their proceedings, left

the siege of Glenbervie, with which he was then engaged, came to Brechin

overnight with the most courageous of his troops, knocked down the watch,

surprised the town, fell upon the gallant lords, drove them from the city,

and took possession of the town and castle of Brechin. Next morning, the

lords of the king’s party, being informed of the few troops which Auchindown

had with him, collected their scattered forces and marched to Brechin to

give him battle. Gordon courageously met the lords, routed them, and slew

about eighty of their troops, but generously dismissed, without ransom or

exchange, nearly two hundred prisoners, most of them gentlemen.

Alexander Scott, who wrote in

1562, is said to have been a native of Brechin. Of this there may be doubt,

but it is probable he was in some way connected with the burgh, for we have

heard his poems recited by individuals in the town, who represented that

they had the verses handed down to them by tradition. One of these poems

struck us as particularly plaintive. It is entitled “ An Address to the

Heart," and runs thus:—

“Return thee hame, my heart,

again,

And byde where ye war wont to

be;

Thou art ane f ule to Buffer

pain

For luve o' ane that luves no thee.

“My heart, take neither strute nor wae

For ane, without a better cause;

But be thou blythe and let

her gae,

For feint a crum o’ thee she

fa’s.

“ Ne'er dunt again within my

breast,

Nor let her Blights thy

courage spill,

She *11 dearly rue her ain

belieist,

She *s sairest paid that gets

her will.”

As the close of the sixteenth

century is the close of the connexion of the Popish hierarchy with the

cathedral church of Brechin, we may here take a hasty glance at the

constitution of. the chapter, and at the altarages and chaplainries

connected with the cathedral during the time of Papacy, as stated in the

documents still existing. The charter by Robert I., in 1322, granting a

right of market on Sundays, is addressed to the bishop, chaplains, and

canons of the cathedral church of the Holy Trinity of Brechin. Amongst the

old records there is an apostolic declaration dated on the Monday of the

Holy Trinity in 1372, issued by Patrick, Bishop of Brechin, and the canons,

rectors, vicars, and elders of the diocese, for the purpose of ascertaining

the number and quality of the benefices belonging to the church, and the

dignities, offices, and prebendaries belonging to the cathedral. By this

writ it is declared that there are eleven benefices belonging to the church,

four of which have the dignity of dean, chanter, chancellor, and treasurer,

and the fifth has the dignity of archdean, which five benefices are

incompatible with other offices. Then it is declared that there are six

benefices,— viz., vicar, pensioner, subdean, Kilmoir, Butergill, and

Guthrie, all of which are simple prebends, and are compatible with other

offices; and it is further stated that although two of these prebends are

commonly called vicar and subdean, yet they have no care of souls, nor

prerogative of dignity, nor office, nor administration, within or without

the cathedral, but only that, as already said, they are simple prebends

compatible with other offices. The witnesses to this letter are described as

Fergus de Tulach, praecentor; Richard de Monte Alto, chancellor; Matthew de

Abirbrothoc, treasurer; Stephen de Cellario, archdean; William de

Dalgarnock, vicar; Radulph Wyld, subdean; John de Drum, prebend of

Butergill; Thomas de Luchris, prebend of Guthrie; John Wyld, rector of

Logie; John de Gaok, rector of Monzeky; and Alexander Doig, vicar of

Dunnychtyne, canons of the church; the dean and the pensioner, dwelling at a

distance, and the prebend of Kilmoir, being only absent. In the park of

Burghill, not far from the keeper’s house, there is a round knoll planted

with trees, where it is understood the chapel of “ Butergill” stood, and

where yet the remains of humanity may be found, indicating that a graveyard

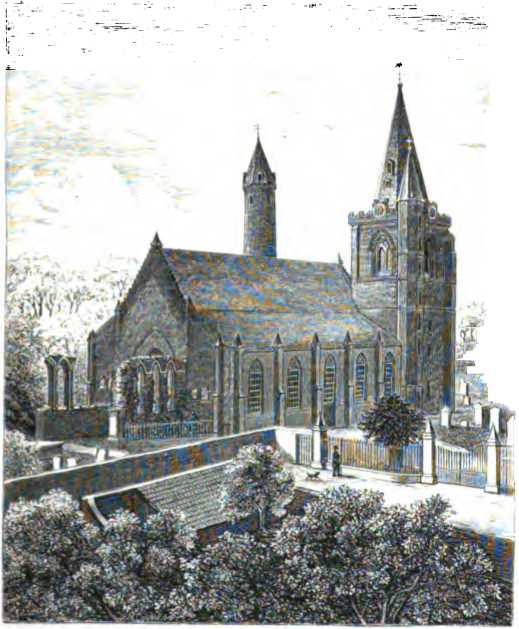

VIEW FROM THE NORTH-EAST

had surrounded the chapel,

while a well of excellent water near at hand proves that the comforts of the

living had been provided for, and that the mansion of the priest had not

been far distant. John of Drum, we presume, had his dwelling, if not his

church, on the farm of West Drums, on the estate of Aldbar, where the

remains of buildings and enclosures are still to be seen in a field called

the chapel field. Kilmoir, or the church of St Mary, is understood to have

been within the policies of Brechin Castle —not far from the castle itself,

and only at a short distance from the cathedral. A few years after the date

of this famous “ declaration—that is, in 1384,—the church of Lethnot was

created a prebendary of the cathedral of Brechin, at the request of Sir

David Lindsay ofGlenesk, the patron of the parish of Lethnot; and the

prebend of Lethnot was declared a canon of the cathedral church of Brechin,

with a stall in the choir, and a place in the chapter. In 1429, we find a

deeree of the bishop and chapter, by which, amongst a variety of other

matters, it is again declared that there are four dignities in the church,

here called the dean, praecentor, chancellor, and treasurer, who have the

precedence of all other canons. In August 1435, the bishop and chapter enter

into a curious agreement amongst themselves to keep the ornaments of the

church in suitable condition, under the penalty— the bishop, as a prebend,

of ten merks; the dean, praecentor, archdean, the vicar, and the ministers

of Lethnot and Glenbervie in five merks each, and every other canon in forty

shillings. In 1474, the parish church of Finhaven was, at the request of the

Earl of Crawford, erected into a prebendary of Brechin, and, of course, the

clergyman would have a prebend’s stall in the cathedral.

With the eleven benefices

declared in 1372, and the additions of Lethnot in 1384, and Glenbervie, as

just mentioned, in 1435, and Finhaven added in 1474, and of the bishop

himself as a prebend, claiming we believe to be rector of Brechin, the

chapter of the cathedral church of Brechin consisted in all of fifteen

canons.

In a charter dated in 1469,

there is an allusion to a tenement commonly called “Cattiscors,” lying at

the south end of the city of Brechin, on the west side of the road leading

to the bridge of Brechin, and situate between

the lands of John Cockbum and the north brow of the brae towards the south

gable of the Little Mill of Brechin. This Cattiscross had stood somewhere

near the present South Port, but what description of a cross was eo named

cannot now be known.

Connected with the cathedral,

there were several chaplainries. A writing dated September 1630, makes

mention of the chap-lainry of St James the Apostle, and this is the only

time we find that chaplainry alluded to, except in a grant for life in 1588

to David Balfour of the “ chaplainry of St Ann, founded at the altar of St

James within the cathedral kirk of Brechin/' “ St James’ land,” however, is

mentioned in 1491 in the Acta Dom. Concilij as being within the city, and in

the title-deeds of a property lying on the east side of the High Street and

south side of the Blackbull Close, the subjects are described as belonging

“to the Chapplenary of the altar of St James, situate within the cathedral

church of Brechin/* This properly now belongs to Mr Lawson, baker. The

chaplainry of St Mary" Magdalene undoubtedly belonged to the cathedral of

Brechin. This chapel was situated on the lands of Arrat, between Montrose

and Brechin, close by the present turnpike road, where a burying-ground

still exists, known as “Maidlen Chapel.” In old writings the chaplainry of

Mary Magdalene is called sometimes the Chapel of Arrat, and sometimes

the Chapel of Caldhame, from lands adjoining Brechin on the east side of

the town which belonged to the chapel, and on part of which the railway

station now is, and a new town is fast arising. These lands were thirled to

the Little Mill of Brechin, and the chaplain was obligated to aid in

upholding the mill, cleaning the dam, and bringing home the mill-stones. The

origin of the chapel is unknown, but it was repaired during Bishop Camoth’s

reign, 1429-56, and the revenues were augmented about that time by the

addition of the revenues of the Holy Cross founded by Dempster of Carreston.

The chapel, together with the other property belonging to the altarage, was

gifted by James VI. to John Bannatyne in 1587, for his maintenance “at the sculeis,” and subsequently the emoluments were drawn by the Hepburnes and

the Livingstones. To the cathedral of Brechin also belonged the Maieondieu

chapel, situated in the lane running west from the Timber-market—now called

Market Street— the property of which was managed by a person styled “ the

master of the hospital of the Virgin Mary of Mazendeu.” It is said there was

a monastery of Bed Friars or Trinitarians in Brechin, so designated from

part of their garb, but whose correct name was Ordo Sanctissimse Trinitatis

ad Bedemptionem Captivorum, hence sometimes called Trinitarians. The Society

for Promoting the Fine Arts in Scotland, published in 1848 a plate

representing Italian peasants entertaining a brother of this order. We never

could trace out any property which had belonged to such a body, nor is the

slightest allusion made to them in any writing that has come under our

notice. We have, amongst the papers of the town, allusions also to the

chaplainries “Nomine Jesu,” St John the Evangelist, and St Laurence,

although probably the different names might have been given occasionally to

the same chapels.

The altarages within the

cathedral were still more numerous. There was the altarage of “our Lady,”

where mass was ordered to be said daily at the second bell in the morning,

“at all seasons in the year,” for the souls of Walter, Palatine of Strathearn, and his successors; and to this altarage several properties in

the vicinity of the present Mill Stairs belonged, as well as certain

subjects in Montrose, and some property in Dundee. In 1537, James Leslie,

chaplain of the chaplainry commonly called “Berclay Stall,” grants 13s. 4d.

to the church from his lands in the town of Brechin, which we presume to be

the same as the altarage of the Virgin Mary founded by the Barclays. There

was also the altar of St Thomas the martyr, founded by Sir John Wishart of

Pitarrow, Knight, about the year 1442, to which certain revenues belonged,

payable out of the lands of Bedhall, Balfeich and Pittengardner. There was

likewise the altarage of “the blessed virgin Katherine,” to which a worthy

citizen, Robert Hill, in 1453, gave an acre of land at the Crofts, and a

tenement within the town; which example is subsequently followed by other

citizens, no doubt no less worthy in the eyes of the church. There was

further, the altar of St Christopher the martyr, to which a John Smart left

certain lands and annual rents in 1458. And there was the altarage of St

Ninian, to which considerable property within the burgh belonged. We

likewise have mention made of the altars of St Nicholas and St Sebastian,

the martyrs, in 1512, and that of All Saints in 1537, of which latter Sir

Thomas Finlayson was chaplain in 1547, and which is then described as having

been founded by Mr William Meldrum, archdean of Dunkeld, and to have had

belonging to it, amongst other properties, the land’s called Scale's Acre,

where the Crofts markets were formerly held, now the principal sites of

Panmure Street and Clerk Street The altarage of the “Holy Cross” is

mentioned in 1435, and there are allusions likewise to those of St Duthoc,

St Magdalene, St George, and others incidentally. A piece of ground termed

“Kirk Dur Keyis,”—Kirk Door Keys,—is described in a charter of 1578 as lying

between the lands of Unthank and Caldhame, on the east side of the road

leading to Unthank, being, as we understand, the first field of that

property on the east side of the Toll Road, going northwards from Brechin.

The records of the burgh

contain no reference to the existence of the plague in the town about this

time, but in the accounts of the burgh of Aberdeen we find this entry on

18th August 1597, “Given to Michael Fergus, poist, for careing of a letter

to the baillies of Brechin anent the plaig, lib. 10s.” |