|

Hitherto we have been dealing

chiefly with romance and conjecture, and little that we have said is

absolutely certain, except that Brechin was the seat of a bishop in the

reign of David I. previous to 1153. Perhaps the world might have moved on in

its usual course although this important fact had not been so distinctly

established as it certainly is. Connected thus early and thus closely with

the Church, Brechin seems to have derived its chief importance and support,

for long after, from the same source. We have made up a list of the bishops

of Brechin, and have collated the list with various histories and other

documents; but as it is a record chiefly of dates and names, we think it

better to throw it into a section by itself, than to interrupt the flow of

events by discussions here on the subject of the succession of these

dignitaries, and accordingly it will be found in our Appendix, No. II.

Amongst the earliest grants

to the Church of Brechin extant, is a charter, without date, but believed to

have been given about the year 1222, granted by Randolph “ de Strathphetham,”

supposed to be equivalent with Strachan, of the lands of Brectulach,

understood to be Brachtullo in the parish of Kirkden, “pro anima mea et

animabus omnium antecessorum meorum.” The chapel of “ Messyndew,” still so

pronounced, but now written Maisondieu, was founded by “ Willelmus de

Brechine, fllius Domini Henrici de Brechine fllij Comitis David,” that is,

by William of Brechin, the son of Lord Henry of Brechin, who was the son of

Earl David; hence the chapel was founded by Sir William of Brechin, grandson

of David Earl of Huntingdon and Garioch,

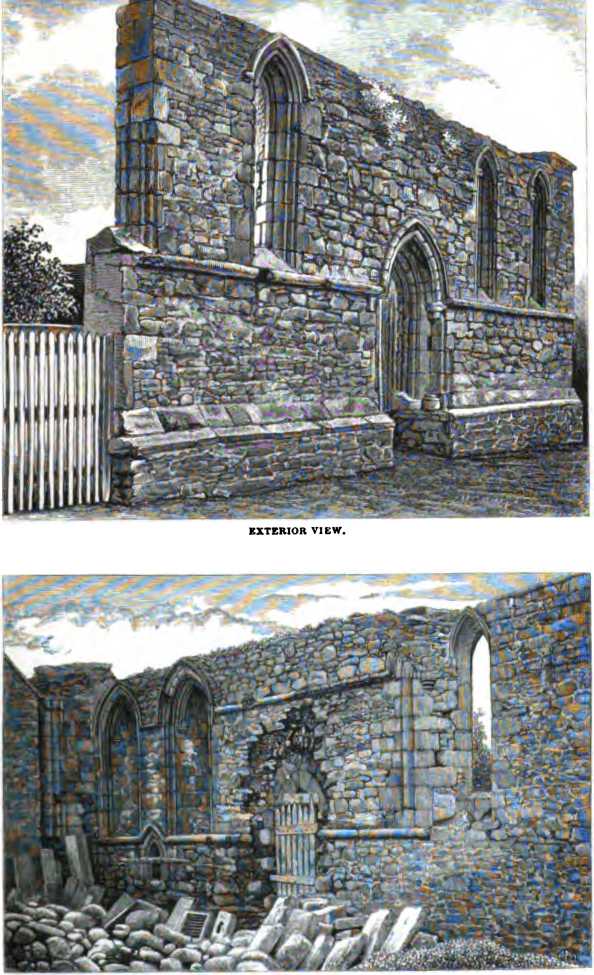

INTERIOR VIEW.

Lord of Brechin and

Inverbervie, and brother of King William the Lion. The charter, which is

witnessed by Albin, who was Bishop of Brechin from 1247 to 1269, is

understood to have been granted about 1256. By it William de Brechin gave

the mills of Brechin and other lands to God and the Chapel of the Virgin

Mary, by him founded, and to the master and chapter and poor of the same,

and that, as the charter bears, for prayers for the safety or good estate of

William and Alexander, kings of Scotland; “Dominis Johannis Comitis

Cestrie;” of Lord Henry his father, and Lady Juliana his mother; and of his

own soul; and of the souls of all his predecessors and successors and of all

the dead in the faith; a sufficiently long but not uncommon catalogue in

those days of parties to be remembered in prayer. In 1267, William again

gives a fight of a road to his favourite chapel, and the charter says the

grant is made to God and the blessed Virgin, “et Domui Dei de Brechine.” A

precept of sasine of Easter Dalgety in the charter-room of Kin-naird,

granted in 1549, is thus styled on the back,—“Factum per Dominum Wuillielmum

Carnegie de Messindew, Roberto de Kennaird,” while in the body of the deed

Mr Carnegy is styled “ Preceptor Domus Dei sive Hospitalis dive Virginis

Marie infra Civitatem Brechinensem; ” thus showing the identity of the

hospital o! the Virgin Maty and the preceptory of Maisondieu. William de

Brechin was one of the regency favourable to England appointed during the

minority of Alexander III., as mentioned in Rymer, Fcedera, i. 563. Robert L

seems to have been a great friend to the church of Brechin. In 1308 he

prohibits the people of Forfar from interfering with the bishop and canons

of Brechin; and two years .after, by a charter dated at Brechin 4th

December, in the fourth year of his reign, he relieves the church of Brechin

of all secular services. The same King Robert, by a charter dated at Scone,

10th July 1322, in the sixteenth year of his reign, gave to John, Bishop of

Brechin, and to the chaplain and canons of the cathedral church of the Holy

Trinity of Brechin, the privilege of haring a market within the city on

Sundays, the same as had been formerly conferred upon them by the former

kings of Scotland,.and as had been possessed by them in the time of

Alexander “ of good memory,” his predecessor; and to that effect Robert

commanded all justiciaries, sheriffs, provosts, and their bailies to defend

the bishop therein. This John was of the family of Kinnymond of Fife, and

appears to have been a decided friend of King Robert Bruce; for in 1309, he

is one of the bishops who solemnly under their seals recognise Robert's

title to the throne of Scotland. The revenues of the see at this time were

£416, equal to £2000 at least of the present day. Bishop William, who was in

the see previous to John, was a man of a different stamp, for he was one of

the few Scots clergy who, in 1290, addressed Edward I. of England,

entreating that monarch to marry his son to Margaret, “the Maiden of

Norway,” heiress of the crown of Scotland. It is comfortable to reflect,

however, that if at this period there was a servile bishop, William, of whom

little more is known than the circumstance just noted, there was also one

generous spirit connected with the burgh, the noble and independent Sir

Thomas Maule, governor of Brechin Castle, whose name is immortalised by the

check he gave to the troops of Edward, and by his gallant defence of the

castle for three weeks in 1303. Against this castle Edward brought a then

famous engine of attack called the War Wolf, which discharged stones of two

or three hundredweight. Sir Thomas Maule is reported to have stood on the

walls of Brechin Castle wiping away with his handkerchief, in derision of

the besiegers, the rubbish caused by the War Wolf, till the engine swept him

away. Tradition has it that Sir Thomas was slain on the bastion still

existing at the south-east comer of the castle wall, and that the stone

which killed him was thrown from the high ground to the east of the ravine

running between the castle and the town of Brechin. Some years ago, when the

earth was tirred from the garden on the top of the bank alluded to, a skull

was found buried, having a nail in it, supposed to have been one of Edward's

soldiers, killed by some instrument fired from Brechin Castle—for gunpowder

was partially in use by this time. Perhaps it is to Edward’s invasion of

Scotland that we are to attribute the want of documents connected with the

earlier history of Brechin, and the necessity for King Robert renewing the

right of market; for Buchanan tells us, so inveterate was Edwards hatred to

Scotland, that when he returned to England after this invasion, “histories,

foedera, monumentaque vetusta, sive a Romanis relicta, sive a Scotis erecta,

destruenda curavit; libros omnes, literarumque doctores, in Angliam

transtulit” Edward is said to have come to Brechin on the 6th, and to have

obtained from Baliol the surrender of the Scottish crown and kingdom at

Brechin on the 10th July 1296, in a very humiliating manner, in the castle

of Brechin, where the Great Seal of Scotland was broken to pieces. Sir David

de Brechin, nephew of King Robert the Bruce, an accomplished knight, and who

had signalised himself in the Holy War, suffered the punishment of treason

in 1320, in consequence of having joined William de Soulis and others in a

treasonable conspiracy against King Robert Sir David appears to have long

tampered with King Edward 1. of England, and to have been opposed through

life to Bruce's pretensions, although often receiving pardon and favour from

the king his uncle. Tet on 10th March 1354. King David, son of Robert Bruce,

grants to “Alexander de Berkeley et Catarine sorori mee spouse sue," the

lands of Wester Mathers, by a charter quoted in the Miscellany of the

Spalding Club, vol. v. p. 248; thus showing the reconciliation of the

families of Bruce and Berkeley.

The induction of Bishop Adam

into the see of Brechin in 1328 displays the grasping spirit of the Church

of Rome. There is a bull by Pope John, dated 31st Oct of that year, printed

by Mr Chalmers in his Register, vol. iL p. 389, apparently confirming Bishop

Adam in the see, but- ia reality claiming the right to nominate the bishop,

and the same Pope by subsequent documents claims the same right in regard to

the canons. Pope Clement VI., following up the tactics of Pope John, by a

bull dated 20th Feb. 1350, states that he had reserved for his own disposal

the provision to the church of Brechin on the decease of Bishop Adam, but

that in ignorance of this reservation the chapter had unanimously elected

Philip, dean of the church, to be bishop; and that Philip, in like

ignorance, had consented to the election, but on being informed of the

reservation had come to Rome and explained the matter, and therefore the

Pope had of new appointed him to the office. Previously, in 1320, Robert

Bruce, in a Parliament held at Arbroath, had asserted the freedom of

Scotland in opposition to the claims of Popedom. Theiner, in his “Vetera

Monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum,” gives, p. 306, a bull by Pope Innocent

VI., in 1354, dispensing with the objection to the marriage of John

Mongombry and Elen More because they were cousins; and p. 312, another bull

by the same Pope dispensing with a similar objection to the marriage of

David de Berclay and Elizabeth Countess of Fife, both bulls being addressed

to the Bishop of Brechin.

The privilege of market

renewed by Robert L was confirmed by David II., who, on 26th October 1359,

was pleased to grant a charter stating that “for the fear and reverence of

God, by whom kings reign and princes govern,” and in respect of the troubles

and dissensions throughout the kingdom, by which the monuments of the church

had been lost, therefore he confirmed to the cathedral church of Brechin the

whole privileges formerly granted by his ancestors, and especially by his

father, to the cathedral church of the Holy Trinity of Brechin. The bishop

of this period was Patrick de Leuchars in Fife, a favourite at court, and

one of those who took an active part in the redemption of David from the

English. Still the right of market, thus guaranteed by repeated royal

grants, seems to have been disputed from some quarter or other—by Montrose,

we believe, for we find “Ane Inchibitioun for halding off mercats of

StapiUhand at Brechine and Fordoune ” to the prejudice of Montrose, issued

by King David II. in 1352. However, there is a “cognition” taken regarding

the Brechin market in 1364 by Walter de Biggar, chamberlain of Scotland,

John de Rossy, John Lamby, David de Foulertoun, John de Allardice, and other

gentlemen; and thereafter we find David, in 1369, giving a new charter to

Bishop Patrick, stating that the whole merchants inhabiting the city of

Brechin had free ingress and egress to the waters of Southesk and Tay for

carrying of their merchandise in boats and ships, upon paying duties

accustomed, and that notwithstanding of any grants to the burgesses of

Dundee and Montrose, who are strictly prohibited from troubling the

merchants of Brechin. This grant was confirmed by Robert II. in 1372; and

the same prince, in 1374, addressed a precept to his justiciaries, sheriffs,

and provosts, charging them to defend the Bishop of Brechin and the canons

of the cathedral church of Brechin in all their lands and privileges. James

II., by a charter dated in September 1451, again renews at great length the

rights of trade granted to Brechin; but Dundee, alarmed at the growing

importance of Brechin, enters a protest against this and the previous

charters, “purchased of false suggestion by information of partial persons/'

as a document quoted by Mr Chalmers proves.

The earls of Crawford were

great benefactors to the church of Brechin in the fifteenth century; and

some grants or charters are still preserved having the arms of that family

attached, impressed in a bold and handsome style. The members of the family

of Dun appear also to have been zealous supporters of the cathedral. The

church having acquired right to the lands of Eaglesjohn for payment of

certain quit rents to Sir John Erskine of Dun, that knight, in 1409,

mortified these rents to the bishop, from reverence to the Holy Trinity, and

from the more secular feeling of affection to Walter,, then bishop of

Brechin. The lands thus conveyed to the church in 1409 are at present called

Langleypark and Broomley, the latter now again belonging to the laird of

Dun. The Duke of Albany, while governor of Scotland inr 1410, granted a

precept to Alexander Ogilvy of Ouchterhouse, Sheriff of Forfar, for

examining into the marches of certain lands belonging to the bishop; and

thereupon the sheriff gives a decree in favour of the bishop addressed “tyll

all yat yir letters heirs and seis,” “gretyng in God aye lestand,” and

stating that “Walter, throu Goddis sufferance Bischope of Brechin, fand ane

borch in our hand as schref,” which the lairds of Kinnaird “ recontret.”

There is still extant amongst the papers of the burgh a curious precept by

James I., in 1427, by which, for the growth of grace, and various other

ostensible reasons, he grants different sums to the cathedral, payable out

of hi6 annual rents of the city of Brechin; and amongst the individuals from

whose lands these sums are payable, we find the names of William White,

Bichard Lindesay, possessor of the “Forkit Akir,” David Garden, John Durward,

LaurenceSmith, John Guthrie, proprietorof certain lands between the two

vennels; John Tindall, James Myres, James Potter, John Saddler, and John

Walker, names still common in Brechin. But the chief friend to the church of

Brechin at this early period, was Sir Walter Stewart, Knight, Palatine of

Strathearn, Earl of Athole and Caithness, and Lord of Brechin and Cortachy,

which latter title and property he assumed, together with the lands of

Brechin and Navar, &c., on marrying the heiress, Margaret, only child of

Barclay, Lord of Brechin. On 22d October 1429, by charter dated “ apud

Castrum nostrum de Brechynhe gifted £40 Scots, payable annually, to the

church from his lands of Cortachy, and failing thereof through war, poverty,

or other cause, from his lands and lordship of Brechin, for the maintenance

of two chaplains and six boys to perform divine service within the choir of

the church. He also in the same month bestowed the patronage of the church

of Cortachy on the cathedral; and, further, he gave a piece of land lying on

the west side of the city of Brechin, adjoining to the Vennel, for the

residence of the boys and chaplains. In these grants, and in a relative

obligation by the bishop, there are long directions about the clothing of

the boys, and in regard to their education and demeanour. In particular, the

lads are prohibited from going to the fields without one of the chaplains,

and they are ordered, on these occasions, to be clothed in open coats,

purple or white, and to have their hair neatly dressed. In regard to the

chaplains, again, it is provided that one of them shall be instructed in

music and the other in grammar, which branches of education they are to

study in the hours when they are free from spiritual duties. It is curious

to find the bishop, so early as 1435, backing out of his part of the

obligation, and upon various pretences reducing the two chaplains to one,

and of course reducing the duties to be performed; and the duties thus

reduced seem to have been but indifferently attended to, for, in 1524, there

is a decree of the bishop of that period deciding various differences which

had arisen between the chaplains and the chapter of the cathedral for

non-performance of duties. It is no less curious to remark, that Walter,

Earl of Athole, who made these liberal grants to the cathedral of Brechin,

was the son of Robert II. by Euphemia, daughter of Hugh, Earl of Ross, and

was suspected, from a desire to ascend the throne, of having been the means

of procuring the deaths of most of his own relations. Ultimately, he was

himself put to death by lingering tortures protracted for three days, in

consequence of being the . principal instigator of the murder of his nephew,

the courtly James I.

The bishop who was so

particular about the exterior and interior of the heads of the chaplains and

of the boyB, was a John Camoth, a gentleman and a courtier, for he was

selected to accompany Margaret, daughter of James I., to France, when she

was espoused to the Dauphin, afterwards Louis XI, In the chronicle of the

reign of James II. kept at Auchinleck, there is an entry bearing that John

Crenok, Bishop of Brechin, died there in August 1456, “that was callit a

gude, actif, and vertuis man, and all his tyme wele gouvemande.” Apparently

this bishop had gone 'more than once to France, for amongst the records of

Brechin there is an instrument bearing that Bishop John, in a synod held on

14th April 1434, narrated that in his last voyage from France, probably a

stormy one, he had vowed to give to the church of Brechin two silver

candlesticks, in acquittance of which vow he then delivered to John Liall

the treasurer of the church six silver cups, gilt on the edges, and also a

silver gilt cup with cover, the cover having the rays of the sun engraved

upon it, this last cup to be for the exclusive use of the dean and canons at

their common festivals. Judging from the documents left, we would say that

there was more business done during the reign of this bishop than during

that of any other bishop. He it was who, in July 1450, obtained an

inquisition by which it was ascertained that the inhabitants of Brechin had

a right of market on Sundays, and liberty of trading between the waters of

Southesk and Tay. Amongst a variety of other grants obtained by this bishop

to the church, we may notice that by Alexander Cramond, laird of South

Melgund and Aldbar, of an annual rent of £26, 8s. Scots, payable from a

tenement called Lammyslande; a similar grant by John Sievwright, citizen of

Brechin, and a conveyance to the cathedral by Robert Hill of a tenement

lying near to that of John Tod, and an acre of arable land in the Crofts

adjoining the land of Patrick Guthrie and John Masson. We may also refer to

a charter by Mr Thomas Bell, vicar of the parish church of Montrose, of some

property in Murray Street of Montrose, witnessed on 20th June 1431 by

Patrick Barclay, then provost of Montrose, and John Niddry, bailie, names

still to be found amongst the municipal rulers of that burgh.

Besides acquiring property

for the church, bishop Carnoth seems to have acquired property for himself.

Thus on 13th February 1444, David Conan conveys to the bishop the

Temple-hill of Keithock, to be held of the master of the hospital of St John

of Jerusalem, for payment of a yearly feu at two terms, Pentecost and St

John in summer; and this property is ratified to the bishop in 1450 by

brother Henry de Livingston, a knight of the order of St John of Jerusalem,

commendator of the preceptory of the same, and “Magister de Torfechyn.” If

we mistake not, these lands are now known as the Templehill of Bothers, and

form part of the estate of Caimbank.

A dispute appears to have

arisen during this bishop’s reign which may afford evidence for fixing the

period when either the steeple or the round tower of Brechin was erected. Mr

David Ogilvy, rector of the parish church of Lethnot, having failed to pay a

sum of 28 merks, said to have been due from the income of the church of

Lethnot to the bishop and chapter of Brechin, was repeatedly cited to appear

before the consistorial court He treated the summonses very lightly, and

neglected to appear; but a court was held by Robert Wyschart, rector of

Cuykstoun, in the diocese of St Andrews, as substitute of the bishop, at

Brechin, on the 9th of February 1435, when, after the examination of a

variety of witnesses named, it is recorded as having been proved that

Lethnot was liable in 28 merks annually to the church of Brechin; and that

in part payment of this debt, Henry de Lechton, vicar of Lethnot, had

delivered to Patrick, Bishop of Brechin, (1354-84,) a large white horse, and

had also given a cart to lead stones for the building of the belfry of the

church of Brechin in the time of Bishop Patrick, and which cart was made by

Elisha Wright, then residing at Finhaven. These are the words of the

decree:—“Quarto, Ponit et probare intendit quod quondam nobilis vir Henricus

de Lechton arrendator dicte ecclesie pater Johannis de Lychton soluit et cum

effectu realiter deliberauit renerendo patri domino Patricio episcopo

Brechinensi et capitnlo eiusdem unum magnum equum album in partem solutionis

dicte pensionis. Quinto, Quod idem Henricus de Lechton ad ducendum lapides

ad edificationem campanilis ecclesie Brechi-nensis tempore quondam domini

Patricii episcopi Brechinensis realiter et cum effectu dedit unum currum

quem fecit Elisius Wrycht tunc commorans apud Fynnewyn super le bank de

Lymyny in partem solutionis dicte pensionis.”—R. E. B., voL i. page 74.

During Bishop Caraoth’s

reign, and on 28th May 1445, King James II. gave to John Smyth, citizen of

Brechin, the hermitage of the Chapel of the Blessed Mary in the forest of

Kilgerre, lying in the barony of Menmure, with three acres of arable land

which had formerly belonged heritably to Hugh Cuminche. This hermitage is

understood to have been somewhere on the south face of the hill of Caterthun,

and the prayers which the hermit was bound to offer for the king and the

other duties of the office likely had not been severe.

Bishop Carnoth himself seems

to have been a builder, but to what extent we cannot say, only we find, in

1579, a grant by the then bishop of a piece of ground “ tending along by the

wall and street onward to the gate of the tower called Carnock's Tower,1'

being, as the document leads us to infer, the gate or entry now called the

Bishop’s Close, on the west side of the High Street.

The reign of this bishop,

good and worthy as he is reported, appears to have been rather stormy, for,

in 1439, we have an instrument bearing that Mr Thomas Lang, chaplain of the

choir, protested against the bishop’s bailie for having given possession to

William Foote of a tenement on the west side of the High Street, belonging

to the chaplains, and asked if, by securing the tenement and putting out the

fires thereof he could interrupt the possession ; and upon these threats he

takes instruments in presence of Alexander Fotheringham, John Forrest,

Walter de Craig, and a variety of others. Again, there is a protest in 1439

by the bishop against certain convocations alleged to have been improperly

held in his absence, in one of which it is said the chaplain had been

removed from the prebend’s stall in the church of Lethnot, and a boy put

into the chaplain’s place. There are also a variety of documents bearing

upon a claim which this bishop had, or pretended to have, upon the lands of

Marytown, occupied by William Fullarton. In this dispute, Janet Ogilvy,

widow of Fullarton, just does as the bishop bids her; but her son Patrick

takes a different course. While in August 1448 the bishop is engaged in a

dispute with his dean and archdeacon about taxes that ought to have been

recovered from the canons for repairs of the choir.

Besides being thus actively

engaged, Bishop Camoth procured transumpts or authentic copies of all the

royal grants in favour of the town and cathedral, and obtained ratifications

of them by James II., on 1st September 1451, a most important document for

the burgh. Indeed, the only thing this active man left doubtful is his own

surname, which is variously spelled Carnock, Crenok, Carnoth, Crennach,

Crannoch, and Crenuch, now commonly said to be equivalent with the surname

of Charteris. But the history of the incumbency of this bishop would be

incomplete did we not notice that, during his reign, the boundaries of the

muir of Brechin were first ascertained. By the bishop's influence, James II.

was induced to direct a precept to the sheriff of Forfarshire for the

purpose of ascertaining the marches between the lands of Menmuir, belonging

to John de Collace, and those belonging to the church. The sheriff

accordingly chose an assize, consisting of Sir John Scrymgeour, constable of

Dundee, Richard Lovell of Ballumby, William Lyell of Balna-gerro, Patrick

Rind and James Rind of Carse, Robert Fuler-toun, Henry Fethy of Balyesok,

John Carnegy of that Ilk, Walter Carnegy of Guthere, William Guthere of

Lownan, Walter Carnegy of Kynnarde, David Walterstoun of that Ilk, and

Thomas Lamby; and this inquest report, on 13th October 1450, that the town’s

property began at the east at Threip-haughford in Cruik, extended towards

the west, according to the ancient course of the water of Cruik, by the

lands of “ Bal-zordy,” and went as far west as the lands belonging to John

de Colless of Balnamoon went The inquest also state that they had caused

make a large ditch as a fence between the lands of Balyeordie and of the

burgh, and that right upon the water of Cruik they had placed a cross with a

large stone under it as a march. John Collace, however, does not seem to

have tamely submitted to this marching of the lands, for, in May 1451, we

have an instrument bearing that John, Bishop of Brechin, and Walter de

Ogilvy, Sheriff of Forfar, compeared upon the water of Cruock at the

Threiphaughford, and protested for remeid of law in consequence of the march

stones having been removed from the situations in which they were placed,

and thrown into the water. And in 1458 there is a precept by James II.

directed to the Sheriff of Forfar charging him to command Thome of Cullaiss

to abstain from annoying the community of Brechin in the possession of the

lands decreed to them by the perambulation. This document directs the

sheriff to “summonde and charge ye foresaid Thomas to compeir before ws and

our coun-saile at Dundee ye secund day of ye next justice aire of Anguss;”

so Dundee had been the site of a circuit court previous to the recent Act of

Parliament for the holding of courts there. Notwithstanding of all this,

however, the family of Collace and the inhabitants of Brechin, as the

records of justiciary prove, had battlings till the Collaces sold their

lands to Sir Alexander Carnegy, brother of the first earls of Southesk and

North-esk, in 1632. This Thomas Collace was a favourite at court, for on 23d

March 1499 he got a charter from James IV. confirming to him a right of vert

and venison in the forest of Kilgarry.

It was during the Episcopal

reign of Bishop Carnoth that the battle of Brechin, as it is called, was

fought at Huntlyhill, in the parish of Stracathro, about three miles

north-east of the city. The historical reader will recollect that the Earl

of Douglas was murdered by James II. in Stirling Castle, in February 1452,

because he refused to break a league which he had formed with the earls of

Crawford and Boss. In consequence these noblemen joined the Douglases in

open rebellion to the royal authority. Alexander Gordon, Earl of Huntly, was

advancing with a body of troops consisting of his own vassals, and of the

clans Forbes, Ogilvy, Leslie, Grant, and Irving, with the intention of

joining the royal standard, when he was encountered, on 18th May 1452, at

the Hair Cairn, near Caimbank, by the Earl of Crawford, surnamed “The

Tiger,” from his fierce temper, and “Earl Beardie,” from his immense hirsute

appendage. Crawford was in command of the “ bodies of Angus,” and of the

adherents of the rebels in the neighbouring counties, headed by foreign

officers. An engagement ensued, and. the centre of the royal army began to

give way, when John Coless or Collace of Balna-moon, who bearded the bishop

about the marches of the muir, and who hated Crawford in consequence of some

dispute regarding property, deserted to the royalists with the left wing,

which he commanded, and which was the best equipped part of the troops,

being armed with battle-axes, broadswords and spears. The royal army being

thus enforced, and the rebel party so weakened, Huntly, contrary to

expectations, gained the victory, and gave his name to the hill where the

battle was fought. The Earl of Crawford retired to his castle at Finhaven,

about six miles west of Brechin, and is reported to have declared, in the

frenzy of disgrace, that he would willingly pass seven years in hell to

obtain the glory which fell that day to his antagonist, or as tradition has

it, “that he wad be content to hang seven years in hell by the breers o' the

ee ”—the eyelashes. After his defeat Crawford turned his vengeance from the

royalists towards those who had deserted him, wasting their lands and

burning their castles, and he was left at liberty to do so, as Huntly was

obliged, immediately after the battle, to return home to protect his own

lands from the ravages of the Earl of Moray. In 1562, we notice that David

Fenton of Ogill sold to Robert Collace of Balnamoon, and Elizabeth Bruce his

spouse, the lands of Findoury, which lands they transferred in 1574 to

Robert Arbuthnott. Balnamoon and Findoury are once again united under one

worthy proprietor in the person of James Carnegy Arbuthnott, Esq. In March

1625, we find John Collace, fiar of Balnamoon, witnessing a charter by David

Ramsay, younger of Balmain, to John Moncur of Slains, of the lands of

Cossins and others in the barony of Mondynes and parish of Fordoun, while

between that date and the period of the battle of Brechin, the name of

Collace occurs frequently in connexion with properties in the town and

neighbourhood of Brechin, but of the traitor John Collace himself we have no

further notice. Of Crawford, again, we are told by Buchanan that soon after

the battle of Brechin he took the opportunity of the king passing through

Angus to submit himself to the royal authority, and to make his peace with

King James, to whom he remained firmly attached for the remainder of his

life, which was of but short duration, for he died in 1453. The succeeding

Lord, David Earl of Crawford, seems to have been a man anxious to be on good

terms with the church, for, in the year 1472, he burdened his lands of

Drumcairn, “lying in his lordship of Glenesk,” with £3 annually to the

cathedral of Brechin.

The stormy reign of James II.

did not prevent peculation in the church: at least a precept by James III.

in 1463, states plainly that through the profligacy of the bishops and

canons of Brechin, the revenues of the cathedral had been greatly reduced by

frequent alienations of its property, so that it was then suffering under

great deficiency of its resources, and therefore his Majesty exhorts the

bishop (then Patrick Graham, cousin of the king) to revoke the whole of such

alienations as were made without just cause, and his Majesty orders all

judges to assist the bishop in the recovery of the property, whether lands,

movable goods, or effects. This precept was not allowed to remain a dead

letter. In 1464 a decree of the Lords of Council and Session was issued,

decerning Walter Dempster of Ochter-less to reconvey to the church the lands

of Ardoch, Adicate, Bothers, and Nether Pitforthie, alleged to have been

surreptitiously obtained by him; and Dempster, in 1468, implements the

decree by resigning the lands to the bishop “ upon his bended knees, and

having his hatids closed and within those of the bishop/’ Other documents

import that Mr Dempster, being reconciled to mother church, got back his

lands for payment of an annual feu to the cathedral. The family to which

this gentleman belonged took their surname from the fact of having been

appointed by Robert II. to the office of heritable Dempsters to the

Parliaments, or readers of the doom or sentence pronounced against criminals

in the courts of the kingdom. Patrick Graham was afterwards translated from

Brechin to St Andrews, and died archbishop in 1479—a prisoner in the castle

of Loch-leven, broken-hearted by court intrigues, although a man of strict

morals and considerable learning. Previous to his removal from Brechin,

however, he had the influence to obtain from King James III. a charter,

dated at Linlithgow 29th June 1466, changing the weekly market day from

Sunday to Monday, and of new conferring upon the bailies and citizens of

Brechin all their former privileges. The same monarch, shortly before his

decease in 1488, granted a charter in favour of the bailies and community of

the city of Brechin, by which, in respect of the income of the city being

small, and of the faithful services of their predecessors rendered to the

king in times of trouble, he gives and confirms to them the right of levying

for every horse-load of goods brought to the town, “unum oblum,” or obolus,

which originally was a small Athenian coin of silver weighing about twelve

grains, worth three halfpence at the ordinary price of silver in the present

day, but in the fifteenth century of much more value, and the charter

authorises the magistrates to employ one or more officers to collect the

tax. This charter was produced by the town clerk as a witness before the

House of Peers in 1853 in the case regarding the original dukedom of

Montrose, and is, with the clerk’s evidence, printed in the folio volume

published by Lord Lindsay on that case, (page 404-6;) the charter is also

printed by Mr Chalmers in his “Registrum Episcopatus Brechinensis,” vol. ii.

page 122. We thus refer particularly to the charter as it is a most

important one for the burgh.

James Stewart, second son of

James III., was at his birth created Duke of Ross, Marquis of Ormond, Earl

of Edirdale, and provided with the lands and lordships of Brechin, Navar,

Ardmanach, and Nithsdale. In 1497 he was made archbishop of St Andrews. With

Brechin he appears to have had no connexion further than in drawing revenue

from it.

The register of the burgh of

Aberdeen gives the taxation laid on the burghs beyond the Forth by the

commissioners of the burghs in the Parliament held at Edinburgh in 1483,

when we find the Angus burghs rated thus:—“ Dundee, £26, 13s. 4d.; Forfar,

£1, 6s. 8d. ; Montrose, £5, 6s. 8d.; Arbroath, £2; Breching. £4.” Aberdeen

is then rated the same as Dundee.

The year 1481 was one of

those years of so frequent occurrence in the fifteenth century, when poverty

perished, and even riches scarce supported itself; it was a “dear year”—and

Brechin, like other burghs, suffered severely.

We cannot tell whether it was

the grant of right of custom given by James III., or what it was, that

involved our citizens of Brechin in a dispute with the burgesses of

Montrose, but we find, in 1508, that there was a contest between the two

towns regarding the market, and that the Bishop of Brechin, then William

Meldrum, granted authority for defending the interests of the city of

Brechin, and of the church of Brechin, in an action raised before the Lords

of Council and Session at the instance of the aldermen, bailies, and

burgesses of Montrose, against the citizens of Brechin, for vexations and

hindrances alleged to have been given to the community of Montrose in their

use of the market of Brechin. How this dispute terminated, or whether it is

still in court, we do not know.

In the charter chest of

Viscount Arbuthnot, there is a discharge by this Bishop Meldrum “of the

teind-penny for James Arbuthnott's waird and marriage,” dated the “penult

Maij 1511;” owning receipt of 35 merks, “gude and usual money of Scotland/'

of composition for what would now, at least, be thought a strange demand;

and amongst the documents belonging to the burgh of Brechin there is an

instrument dated in 1508, bearing that John Carnegy of Kinnaird had

delivered a horse, “grosij coloris,” as the Herzdd of the late John Carnegy

his father for the lands of Little Carcary, held of the Cathedral of

Brechin. “Herrezelda” (says Skene, in his “ De Verborum Significatione') “

is the best aucht ox, kow, or uther beast, quhilk ane husbandman possessor

of the aucht pairt of ane dauacb of land, (four oxen gang,) dwelland and

deceasand theirupon, hes in his possession the time of his decease, quhilk

oucht and suld be given to his landislord or maister of the said land.”

Probably this language of Sir John Skene of 1681, our readers may think

requires interpretation itself. The substance of all this however is, that

Bishop Meldrum looked carefully after all the property belonging to the see

of Brechin, and indeed added considerably to it.

Lord Gray preserves in his

charter-room a document, which is a curious specimen of the numerous

hereditary offices that existed in feudal times, being a retour of the

service of Alexander Lindsay, as heir of his father Richard Lindsay, in the

office of blacksmith of the lordship of Brechin; it is dated 29th April

1514, and is published in the Miscellany of the Spalding Club for 1853. By

it the inquest selected from the barons of the shire report on oath that the

late Richard and his forefathers were common smiths of the lordship of

Brechin, and received hereditarily nine firlots of good meal of every plough

and mill of the tenants of Balnabriech, Kintrocket, Pitpullocks,

Pittendreich, Hauch of Brechin, Burghill, Pettintoscall, Balbirnie, with the

mill of the same, Kincraig, and Leuchland; and one fleece of an old sheep

yearly of every one of the tenants of the said towns; and also common

pasturage in the Long Haugh of Brechin for two cows and a horse. No bad

berth this of the blacksmith of the barony of Brechin. We trace the office

further down. On 5th October 1605, in the Speciales Inquisitiones for

Forfarshire, published by order of Parliament, there is recorded the service

of David Lindsay, as heir of Robert Lindsay, in the office of common

blacksmith of the lordship of Brechin, and his right as such to two bolls

one firlot of meal, and pasturage, like his predecessor, with the fleece of

a sheep and a lamb, as his payment for making wool scissors, we suppose, or

“tonsules lame” as they are called here; while in the previous retour they

are termed “forcinij.” The Richard Lindsay first mentioned is, we presume,

the proprietor of the Forkit Akir of which we spoke under the date of 1427,

and which is understood to have been a part of the lands now known as the

Latch. The name of Lindsay, as a blacksmith, occurs for the last time in the

records of the hammermen trade of Brechin in the year 1616.

John Hepburn, who succeeded

to the see of Brechin about 1517, seems, in reference to the property of the

burgh, to have pursuedthe course of Bishop Carnoth. In 1524 he gives out a

long decree finding that the chaplains of the chaplaincy founded by the

Palatine of Strathearn were neglecting their duty, and ordaining them to

build and repair, and to provide proper vestments, and he gets this decree

confirmed by a charter granted by James V. in 1528. On 25th May 1535,

Hepburn procured a cognition by the sheriffs-depute of Forfarshire, James

Gray and David Anderson, regarding the common muir, so full and particular,

that we shall take leave to lay it before our readers. This cognition states

that “in the matter and cause pursued by a reverend Fader (father) in God,

John, Bishop of Brechin, the dean, chapter, and citizens of the same, by our

sovereign lord's letters direct to my lord sheriff of Forfar and his

deputes, purporting in effect that where they 'have the muir of Brechin with

the pertinents pertaining to them in oommonty and their predecessors, and

they have been in possession thereof as common past memory of man, whilk

now, lately, William Dempster of Careston, Janet Oehterlony, his mother,

George Falconer, her spouse, William Marshall, David Deuchar, David

Waterstone, portioner of the lands of Waterstone, Matthew Dempster, and

James Fenton of Ogil, has stopped the said reverend father, dean, chapter,

and citizens of Brechin in casting of peats, turfs, , and fuel upon the said

commonty, and to pull heather thereupon, and has riven out, tilled, and sawn

a part thereof, and built houses upon another part<of the same, tending to

appropriate the said common muir to them wrongously, and to call both the

said parties, and take cognition in the said matter upon the ground of the

said lands, as in our sovereign lord's letters, direct to my lord sheriff

and his deputes foresaid, at more length is contained. By virtue of the

which David Lokky, one of the Mairs general of the said sheriffdom, by the

sheriff principal's precept direct to him thereupon, charged and required

the said reverend father, dean, and chapter, and citizens of Brechin,

followers on the one part, and the said William Dempster, Janet Oehterlony,

George Falconer, William Marshall, David Deuchar, David Waterstone, Matthew

Dempster, and James Fenton of Ogil, -defenders, on the other part, to

compear before my lord sheriff foresaid or his deputes, one or more, to this

said court, day, time, and place in the hour of cause to hear and see a

cognition to be taken in the said matter, and justice equally ministered to

both the said parties, after the tenor of our sovereign lord's letters

foresaid. At the which day, and in the said court, the said sheriffs-deputes

caused call the saids parties, followers, and defenders, to compear before

them the said day and place, to hear and see a cognition taken in the said

matter, as they that were lawfully summoned thereto. Both the said parties

compearing personally, their rights, reasons, allegations being proponed and

shown, together with the depositions of diverse famous witnesses produced

and admitted, and sworn in presence of parties foresaid, and their

depositions, the said sheriffs-deputes being ripely advised therewith, finds

and declares, by cognition taken in the said cause, that the said reverend

father, dean, chapter, and citizens of Brechin, and their predecessors, has

been in peaceable possession of their muir of Brechin foresaid, with their

pertinents pertaining to them, in commonty in time bygone, past memory of

man, bounded on all the parts about as follows—1 st, Beginning at the

gallows of Keithock at the east; from that west to the Muirfauld dyke, and

from that Muirfauld dyke to the Bog dyke, and from the Bog dyke, extending

west to the Park dyke, at the south, extending west to the south side of

Montboy, the Myre of Montboy there along, and from thence extending west to

the gallows of Fearn; and from the gallows of Fearn, east at the north part

to the Qualochty, and from thence east to the gallows of Kethock foresaid;

and decemeth the bounds before expressed: The whole muir to be commonty to

the said reverend father, dean, chapter, and citizens of Brechin: And anent

certain lands and houses that are called Todd's houses, and lands lying

within the bounds betwixt the gallows of Fearn and the gallows of Keithock,

pertaining to James Fenton of Ogil, pertaining to the lands of Fearn, which

has been occupied these twenty years bygone, without impediment of Brechin,

but bruikit (enjoyed by) them peaceably, as it is clearly proved before the

said sheriffs-deputes; therefore the said sheriffs-deputes excepts that

lands and houses in this their process, nought (nothing) hurting the

property of the superior, nor yet the commonty of the same lands and

occupiers thereof, but Bn chin to have commonty over all the muir; and the

said reverend father, dean, chapter, and citizens of Brechin, shall be kept

and defended in such like possession of the said muir as said is, in time

coming, ay and while they be lawfully called and orderly put therefrom; and

also finds, because the said muir is found that it has been used and holden

as common in times bygone past memory of man, therefore the said sheriff

should cause it to be held common such like in time coming, according to

justice, after the tenor, form, and effect of our sovereign lord’s letters

foresaid, and doom given thereupon ; and precepts decerned hereupon,

according to justice.,, We have modernised the spelling and phraseology a

little. The cognition thus formally taken was ratified by the precept of

Lord Gray, sheriff of Forfar, in a court held by him at Forfar, within two

days after the perambulation of the muir by his deputes. On the back of the

original cognition, which is an excellent specimen of the writing of the

sixteenth century, we find this docquet engrossed, “ 23d January 1769,

registered by Mr David Rae, conform to the probative act, and presented by

Charles Guthrie, writer in Edinburgh, to whom the same is returned without

receipt, G. O.”

Hepburn, who took the trouble

of thus fixing the boundaries of the common muir, was descended of the

powerful family of Bothwell, and is reputed to have been a man of great

abilities. He died in August 1558, and Keith says that Listacus de rebus

gestis Scotorum gives the prelate a very large character. But if he was, as

we conceive he was, the John Hepburn who was abbot of St Andrews in 1513,

and who competed with Andrew Foreman for the Archbishopric of that see,

after the death of Alexander Stewart at the battle of Flodden, then he

scarce deserves the very large character here spoken of; for, if Buchanan is

to be believed, Hepburn was a factious plotter, a greedy, ambitious, and

intolerant priest, and the cause of much trouble during the regency of the

Duke of Albany. The documents still in existence in Brechin prove that he

was an active and an intelligent man. As to his moral character, these

documents afford no information. In 1543, during the minority of Queen Mary,

and in the first parliament held after her father’s death, an Act was passed

ordaining that “ it shall be lawful to all our sovereign lady’s lieges to

have the Holy Writ, viz., the New Testament and the Old, in the vulgar

tongue,”—an enactment that sounds strange in our ears, more especially when

it is added, “they shall incur no crime for the having and reading of the

same.” The Archbishop of St Andrews, Chancellor of the kingdom, entered a

protest against this enactment, “ for himself, and in name and behalf of all

the prelates of this realm present in Parliament,” including the then Bishop

of Brechia Hepburn is the last Roman Catholic bishop who has left any

documents connected with the town; for although after his death, and

previous to the Reformation, there was one, and some authorities will have

it two, bishops in the see of Brechin, namely, Donald Campbell and John

Sinclair, there are no writings in existence in Brechin connected with the

Episcopal reign of either of these gentlemen. It is curious enough to

observe that the last document by a bishop of the Church of Rome, remaining

amongst the records of Brechin, is a charter granted by Bishop Hepburn at

request of Sir John Erskine of Dun, the great reformer of the Church, then

the patron of the chaplaimy of the Virgin Mary, in the church of Brechin,

founded by his progenitor, Sir Robert Erskine of Dun, whereby the bishop, in

consequence of the incomes of the two chaplains being insufficient for their

support, unites the two chaplainries into one, and appropriates the income

for the support of one chaplain only. This charter, bearing date 18th and

27th June 1556, is signed by Erskine, in token of his consent to the

arrangement, and completed at Farnell, which then belonged to the bishops of

Brechin as a grange or country residence. The chaplainries being thus

united, “Joannes Dominus de Erskyn ” appoints Nicolas Thomson to the office

of chaplain.

Campbell and Sinclair just

alluded to, although they have left no traces of their reigns in the records

of Brechin, appear both' to have been men of considerable eminence.

Campbell, who was of the family of Argyle, but whose induction into the see

of Brechin is doubtful, died invested in the office of Lord Privy Seal to

Queen Mary in 1562. Sinclair was the fourth son of Sir Oliver Sinclair of

Roslin, and younger brother of Henry Sinclair, Bishop of Ross, and had the

honour, while dean of Restalrig, to join Queen Mary in matrimony to Lord

Darnley. Bishop Sinclair was first an Ordinary Lord of Session ; and

afterwards, on the death of his brother Henry, president of that court, he

was promoted to that important office. By the constitution of the Court of

Session at that period, seven of the members behoved to be laymen, and seven

clergymen, besides the Lord President, who was also required to be a

churchman. Sir Thomas Erskine, Lord Brechin, proprietor of the lordship of

Brechin and Navar, was one of the lords of Session in 1533. He was secretary

to James V., and was unde of, and tutor to, John Erskine of Dun the famous

reformer, mentioned above. In 1584, parochial clergymen were declared

incapable of exercising any office in the College of Justice, that their

minds might not be diverted from their proper functions; and Cromwell, with

that strong spirit of common sense which was exhibited in. most of his

measures, by act in 1650, debarred all clergymen, without distinction, from

sitting on the judicial bench of the Court of Session. After the Reformation

of 1560, several parsons and rectors were lords of Council and Session, but

John. Sinclair, Bishop of Brechin, was the last churchman who was president

of that court

The records of Brechin are

altogether sil&nt on the events which occurred in the burgh when Romanism

was abolished and Protestantism established, and ndther tradition nor

general his-toiy gives any information on the subject We therefore infer

that this change in the religion of the state had created little disturbance

in> the city of Brechin.

We have mentioned previously

that Brechin was regularly assessed along with the other royal burghs for

the maintenance of royalty, and in 1525 contributed £56, 5s. towards the

expenses of King James V. in France. In the division of the money granted

for the defence of the Borders about the same period, Brechin paid £45.

During Mary’s minority the Lord Governor, in 1550, desired a sum to purchase

peace with the emperor, and Brechin gave 40 crowns. In 1556, Mary got a

donation from the burghs, and Brechin contributed £11,5s.; and towards the

expenses of her marriage with the Dauphin of France in 1557, the burgh gave

£168, 15s.; while in 1563, this small city contributed £32, 13s. lid. in

part of the expense of an ambassador to Denmark. But it is perhaps more

worthy of remark, that of the extent of £4144 odds, levied from the burghs

in 1556 to. defray the expenses incurred by Gawin, com-mendator of

Kilwinning, and James Maxwell, “burgess of Rowane, for the down getting of

the xvj deniers of ilk frank wairing of giiids coft be Scotts merchants in

Rowane and Diep by the four deniers payd by them/’ Brechin is assessed in

£36, 11s. 3d. These extracts are taken from the records of the Town Council

of Edinburgh, preserved in the Advocates' Library, Edinburgh. The records of

Convention in March 1575, show Brechin to have been then assessed in £55

towards defraying the expense of sending men to Flanders “for tryell of

falis cunzie.” The records of the Town Council of Aberdeen in 1483, give the

tax-roll of the burghs north of the Forth, as modified by the Convention of

Burghs, in which Brechin is put down for £4, and Montrose for £5, 6s. 8d.,

so Brechin must have been a place of some trade long previous to the

accession of James VI.

But this chapter would be

incomplete, did we not mention that, iii 1503, the courtly James IV. appears

to have visited Brechin on some of his missions of peace amongst his

troublesome subjects. The books of the Lord High Treasurer, preserved in the

General Register House, bear that there were paid “ the xv day of October,

in Brechin, to the foure Italien men-strals, and the more tanbroner to thar

hors met, xlb. vs.” James seems to have been on his way north at this time,

for on the 11th October there is an entry of a payment of 14s. “to Mylson

Harper in Scone;99 and immediately after the Brechin entry there is this

entry, “ Item, that samyn nijcht in Dunnottar to the cheld playit on the

monocords be the king's command, xviij s.” The fondness of James for music

and mirth is matter still of popular tradition, as well as of authentic

history, and on this his journey north he seems to have gratified his taste

to the full. It will not be forgotten that it was in consequence of the

marriage of James with Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII., in the August

of this year, that the Stuarts came to the throne of England, and through

them the Guelphs, the pvesent reigning family. |