|

1. Borrowstounness a Plague-infested Town in 1645

: Special Committee to Prevent Spread of Pestilence: Their

Powers and Regulations : Erection of "Gallases" by Magistrates

of Linlithgow: An Outspoken Skipper Gets into Trouble : Customs

Revenue, 1654: Proposed Bridge over the Avon, 1696—2. Defoe's

Visit to and Description of the Town, c. 1726: Jacobite Soldiers

on Borrowstoun Muir, 1745: Their Depredations: Visit of the Poet

Burns, 1787, and his Impressions—3. Population of Parish between

1755 and 1841: Longevity of Inhabitants: History of Custom House

: Shipping Returns to Admiralty for 1847 and 1848 : Grain

Trade—4. Tambouring and Silk-spinning : The Greenland

Whale-fishing: The Whaling Vessels and their Officers : Sailing

and Home-coming of the Fleet Described : The Boiling House at

the Wynd: The Fire: End of the Industry: 5. Bo'ness Pottery: Its

Various Owners: The Ware Produced: Extent of the Works :

Character and Customs of Potters—6. The Soapwork, Flaxdressing

Factories, The First Iron Foundry: Links Sawmill and Woodyard,

Ropework: The Distillery: The Kinneil Furnaces: The Snab and

Newtown Rows: Kinneil Band : Carriden Band—7. The Carting Trade

: Tolls and Tollbars—8. Educational: Schools and Schoolmasters

in Carriden—9. Those of Bo'ness: The Notorious Henry Gudge :

Kinneil School—10. The Care of the Poor : Interesting Facts and

Figures: The Resurrectionists — 11. The Cholera Outbreaks:

Carriden Board of Health: Its Instructions to the Inspectors—12.

Foreshore Reclamation Schemes: Formation of Local Company of

Volunteers, 1859: The Burgh Seal and Motto.

I.

In this

chapter we conclude by gathering up a number of historical facts

which lie scattered throughout the three centuries embraced by

the present narrative.

Notwithstanding every precaution Borrowstounness.

became a plague-infected town in 1645. So much so that the

Scottish Parliament1 appointed

a Special Committee to prevent the spread of the pestilence. /

Many persons succumbed; and because the seaport was then the

resort of many people from Linlithgow, Falkirk, and other places

the danger of the plague spreading throughout the country was

considerable. Full power was given to the Earl of Linlithgow,

Lord Bargany, Sir Robert Drummond of Midhope, John Hamilton of

Kinglass, John Hamilton, chamberlain of Kinneil; the Provost and

Bailies of Linlithgow, and others, or any three of them to meet

at Linlithgow, or any other place, at such times as were

necessary to cause Borrowstounness to be visited and inspected,

and to do everything requisite. Strict "bounds" were prescribed

the people of the Ness, and they were specially enjoined " not

to come furth thereof without their order under the pain of

death." It may be mentioned that these Commissioners had power,

should any person disobey their commands, " to cause shoot and

kill them." The Provost of Linlithgow, and in his absence any of

the bailies, was to be convener of the rest "upon emergent

occasion." But the people of the infected seaport did not

respect either the commands in the Act or the regulations of the

Committee, and the magistrates of Linlithgow considered that an

"emergent occasion" had arisen, for we find2 that

they "ordaint the Maister of Wark to erect twa gallases—ane at

the East Port, the other at the Wast Port, and gar hang thereon

all persons coming frae Borrowstounness and seeking to enter the

town." No doubt this summary procedure had a restraining effect

on the defiant spirits from the Ness, and we do not expect it

would be necessary to adorn either of the "gallases" with any

victims. On the recommendation of the Committee, Parliament at a

later stage ordained that a collection be made in the shires of

Linlithgow and Stirling for the sufferers in Borrowstounness.

In the troublous times of the Civil War, which

resulted in the beheading of King Charles I. and of his loyal

henchman, the first Duke of Hamilton, one local shipmaster got

into trouble for speaking his mind. The matter came fully before

the Kirk Session, and also the Estates in Edinburgh. The latter

body found it "cleirlie

pro vine that John Watt, skipper, had uttered some disgraceful

speeches against certain of the ministers of this kingdom,

affirming that they had been accessory to the death of the

King." Watt was ordained to pay £100 Scots to the Kirk Session

of Borrowstounness; and "the chairges of the witnesses" who went

to Edinburgh and were examined about the speeches uttered by him

were to be " payt them aff the first end of the said hundreth

punds." Watt was also ordained to acknowledge and confess before

the congregation of Borrowstounness that he was "a lier" in

uttering them; also to find a surety who would become bound with

him that he would never do the like again. A perusal of the old

Scots Acts reveals, among other things, that the Parliament in

1655 fixed the salaries of the officers of Customs and Excise,

and it is incidentally mentioned that the receipts for these

branches of revenue for October, November, and December, 1654,

were estimated at £382 0s. 4£d.; also that in 1701 it considered

a "petition of the poor seamen of Borrowstounness who served in

the Soots frigate commanded by Captain Edward Burd for payment

and relief from the cess imposed on the town and for redress for

wrongs committed by William Cochrane of Ferguslie "; and,

further, that in 1706 an address against the Union was signed

and submitted by several of the inhabitants. But perhaps the

most interesting thing to be found is the authority which the

Parliament granted in 1696 " for the building of a bridge at

Borrowstounness over the Avon and a wall enclosing the road to

it through the grounds of the Earl of Arran," and it also fixed

the bridge toll. This proposal emanated from the seaport during

its first period of commercial prosperity. At that time a very

large quantity of the imports were taken by pack horses to the

west. The only suitable road was by way of Linlithgow, and this

involved the payment of Customs dues to that town. The new

bridge, it was thought, would avoid these, and also give a more

direct means of communication with the west. The Burgh of

Linlithgow protested against the scheme, and apparently some of

the inhabitants of Borrowstounness also petitioned against it.

Whether the funds were not forthcoming, we know not, but the

proposal was not carried into effect.

II.

We must not omit to chronicle that one of the

earliest descriptions of the Ness is from the pen of Defoe,

celebrated as an English pamphleteer and politician, but more

known to fame as the author of "Robinson Crusoe" (1719). His

first visit to Sootland occurred in the year 1706, and lasted

for twelve months. He was then on a mission to promote the

Parliamentary Union of the two countries. In after years he was

frequently in Edinburgh, and his impressions of it and the other

Scottish towns which he visited are recorded in his "Tour

Through Great Britain" (1724-26). In this volume he writes, "Borrowstounness

consists only of one straggling street, which is extended along

the shore close to the water. It has been, and still is, a town

of the greatest trade to Holland and France of any in Sootland,

except Leith; but it suffers very much of late by the Dutch

trade being carried on so much by way of England. However, if

the Glasgow merchants would settle a trade to Holland and

Hamburgh in the firth by bringing their foreign goods by land to

Alloa, and exporting them from thence, as they proposed some

time ago, 'tis very likely the Borrowstounness men would come

into business again; for, as they have the most shipping, so

they are the best seamen in the firth, and are very good pilots

for the coast of Holland, the Baltic, and the coast of Norway."

During the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 a portion

of the Pretender's army on its way to the east country encamped

three nights on the Common or Muir, which lay to the south of

the thriving village of Borrowstoun. The village had a

considerable population of weavers, brewers, and agricultural

labourers. In fact, it is said that it contained four breweries

about that time. The Highlanders during their sojourn there made

free, like Mr. Wemmick, with everything portable. When

remonstrated with by the irate villagers for plundering their

fowls, meal, milk, and butter, the soldiers offered the

oonsolation that they would bring them "a braw new King." Many

of the inhabitants were so alarmed at the wanton depredations

that they buried their valuables in their gardens. Instructions

and warrants had been sent on different occasions through the

Custom-house here to the Sheriff of Linlithgow, the magistrates

of South Queensferry, and the bailie of Borrowstounness

regarding suspected persons and ships. The Custom-house then

contained a number of broad-sword blades and cutlasses, which

formed part of a shipment from Germany. So when here the rebels

conceived the idea of plundering the building, because they were

very indifferently provided with arms. On the Sunday morning

they marched down, with their pipers in full play, to the east

end of North Street, where the Custom-house was then situated,

and succeeded in carrying off some of the weapons and other

articles. The morning after their departure from Borrowstounness

a small silver box, shaped like a heart, was found on the Muir

by the great-grandfather of James Paris, Deanforth, in whose

possession it now is. The workmanship is chaste, and in the

centre of the lid there is a fine Scotch pebble. The curiosity

looks like an old-fashioned snuffbox, although the opinion has

been expressed that it had probably been used for holding

consecrated wafers. In considering this view it is useful to

remember that many of the Prince's followers consisted of Roman

Catholic Highlanders, who, though rude and turbulent, were

devoted to the ceremonial rites of their religion.

In August, 1787, the poet Burns left Edinburgh on

a tour to the Highlands in company with his friend Nicol, one of

the maeter of the High School of Edinburgh They first journeyed

to Linlithgow, then to Bo'ness, and from there to Falkirk and

Carron. His diary contains this entry, "Pleasant view of

Dunfermline and the rest of the fertile coast of Fife as we go

down to that dirty, ugly place, Borrowstounness; see a horse

race, and call on a friend of Mr. Nicol's, a Bailie Cowan, of

whom I know too little to attempt his portrait." Mr. Cowan was

the Duke's baron-bailie. He lived for a time in the old

mansion-house of Gauze, and later at Seaview. It would seem that

he was in the latter house at the time of the poet's call. In

front of it there was then a fine stretch of open shore ground,

upon which horse racing often took place, and it was doubtless

from the bailie's house that Burns watched the sport. From his

references to the view of Dunfermline and the dirtiness of

Borrowstounness it is thought that Burns travelled from

Linlithgow by the easter road, and came along to Seaview through

Grangepans and Bo'ness. The place apparently damped his poetic

ardour, for he did not leave any effusion upon a window pane or

elsewhere. By the time he arrived at Carron the muse had

returned. The visit to the famous ironworks was made on a

Sunday, and admission was refused. Whereupon on a window pane of

an old inn near by he scratched—

"We cam' na here to view your warks In hopes to

be mair wise, But only, lest we gang to hell, It may be nae

surprise; But when we tirl'd at your door, Your porter dought na

hear us; Sae may, should we to hell's yetts come, Your billy

Satan sair us."

To this a Mr. Benson, at that time employed at

the works, and the father-in-law of Symington, the inventor of

steam navigation, penned the following reply:—

"If you came here to see our works, You should

have been more civil, Than to give a fictitious name In hopes to

cheat the Devil.

Six days a week to you and all We think it very

well; The other, if you go to church, May keep you out of hell."

III.

The following figures4 regarding

the population of the Parish of Borrowstounness are noteworthy:

—

In 1755 it was - 2668

In 1795, town, 2613; oounty, 565, - 3178

In 1801, exclusive of 214 seamen, - 2790

In 1811, exclusive of 184 seamen, - 2768

In 1821, exclusive of 158 seamen, - 3018

In 1831,............2809

In 1841,............2347

A table compiled with much care from the register

of deaths for a period of twenty-five years immediately

preceding 1834 shows the number of deaths was 1342. During that

time 167 persons died between sixty and seventy years of age;

227 between seventy and eighty; 119 between eighty and ninety;

and 11 upwards of ninety. The town, in fact, was remarkable for

the healthiness and longevity of its inhabitants.

Subjoined is a list5 cf

the local mechanics in 1796, exclusive of journeymen and

apprentices—

|

Bakers, - - - - |

11 |

Masons and Slaters, |

3 |

|

Barbers, |

5 |

Tailors, |

10 |

|

Blacksmiths, - |

7 |

Shoemakers, |

15 |

|

Butchers, |

3 |

Weavers, |

6 |

|

Clock and Watchmakers, |

2 |

Joiners, Glaziers, Cart-wrights, &c., |

15 |

|

Coopers, |

3 |

Also one surgeon, one writer, one brewery in the

town, and one distillery in the parish.

The Custom-house was removed here from Blackness

through the influence of the Hamilton family; and the first

ledger of the " Port of Borrowstoun Ness " commences on 26th

December, 1707. About the year 1796 Grangemouth, South

Queensferry, North Queensferry, St. Davids, Inverkeithing,

Limekilns, Torry, and Culross were all attached to the

Customhouse here. The annual revenue received, excluding these

creeks, averaged £4000; and the salt duty amounted to about

£3000. Altogether the number of officers employed in the

Custom-house business was forty-four. On the 1st December, 1810,

Grangemouth was erected into a separate port. Thereafter the

area of Bo'ness district and the staff employed were gradually

reduced. In 1845 there was one collector, one comptroller, and

one tide-waiter, and eight others at the creeks still remaining

part of the establishment. Now, the port and district of

Borrowstounness includes the Firth of Forth from the right bank

of the river Avon to the left bank of Cramond Water and midway

to the stream. The establishment consists of a collector and

eight officers.

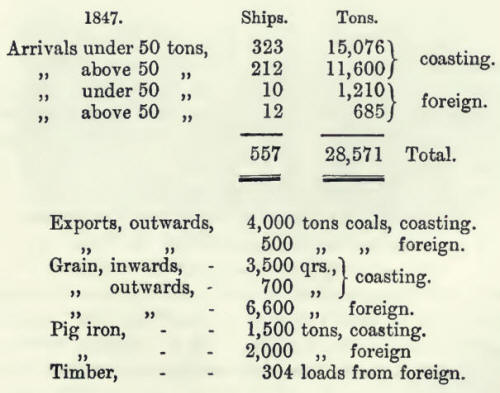

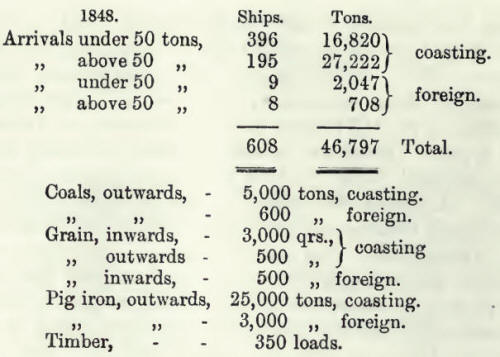

The following returns for two years were sent to

the Admiralty from Bo'ness: —

The corn trade, both British and foreign, was

very considerable. There were three large granaries and some

smaller ones in 1796, with accommodation for upwards of 15,000

bolls. Any rooms which were in repair in the old Town House at

this time were also used as granaries.

IV.

Some mention must now be made of local industries

and manufactures other than coal mining, salt making, and

shipbuilding, which have already been considered. Many of the

women in the town and the country around earned a comfortable

subsistence in the early years of last century by tambouring and

spinning silk. The latter was spun from the waste of

Spittalfields' manufacture, which was sent by sea from London to

agents here. They afterwards returned the yarn to be

manufactured into stockings, epafrlets, and other things.

Tambour work was extensively employed for the decoration of

large surfaces of muslin for curtains and similar purposes. Much

work was done for the West Indies, consisting principally of

light, fancy goods. Many a Bingle woman

and many a widow depended solely on tambouring for their living.

What was known as the "long strike" occurred

about seventy

Henry Bell

years ago. The dispute was between the laird of

Grange and his miners, and the stoppage lasted six months. At

that time Mr. Cadell was heard to say, and with some little

force, "If it had not been for the wives of the miners

tambouring the men would have given in long since." It was fine

work, and some of the colliers' wives and those of the sailors

were dexterous hands at it. They could make as much as 2s. 6d.

per day at the frame. All the light these workers had at nights

was got from a collier's lamp placed in the middle of a saucer,

and great were the fears of the women folks lest the lamp was

upset on the frame. In time pattern weaving was brought to

resemble tambour work so closely that it largely superseded it,

and the old frames were finally laid aside.

About the middle of the last century the

Greenland whale fishing was taken up locally for the second

time, and developed to a much greater extent than before. There

are only a very few alive now who remember this period. Still we

occasionally hear of the narratives of the old sailors and

harpooners concerning their trips to Greenland and Iceland, and

their perilous encounters in these Arctic regions. The port was

the home of many well-known whaling ships, notably the "

Success." The popular refrain with the Bo'ness people applicable

to this vessel was, " We'll go in lucky Jock Tamson's flhip to

the catching of the whale." Besides the "Success" there were the

" Home Castle," the " Rattler" (Captain Stoddart), the "Juno"

(Captain Lyle), the " Larkins" (Captain Muirhead), the " Alfred

" (Captain William Walker), and the "Jean" (Captain John

Walker). The officers on board the "Jean " were William White,

Alexander Donaldson, John M'Kenzie, and John Grant. A line

coiler was paid at the rate of £2 19s.

per month. Each whaler carried a crew of fifty, and was away

many months at a time. The men during the whaling were required

to man the small boats which set out with their harpooners to

the capture of the whales. Sometimes their prize would be so

large as to require six small boats fully manned to tow it to

the whaling ship. The harpooners were looked upon with great

pride by their comrades.

Occasionally they suffered a galling experience

when they failed to hit their mark, or when, after doing so, the

line broke and the whale got away. Harpooner J. M'Kenzie, of the

"Jean," had once an experience of the latter nature which had a

curious sequel forty years afterwards. The "Terra Nova," of

Dundee, captured a whale in which his harpoon was found. The

harpoon bore the name of the maker, William Cummings,

blacksmith, Kinneil, and the year 1853. It was handed over by

the owner of the "Terra Nova" to the Dundee Museum. The late

John Smart Jeffrey, Bo'ness, succeeded in getting the harpoon on

loan, and exhibited it here for a month. Before returning it he

had a facsimile cast for preservation.

There were always great ongoings attached to the

sailing of the whalers, and particularly the "Jean." Women came

down from the mills at Linlithgow, and sailors' wives and

sweethearts were all on the quay. The sailors generally had a

new rig-out of canvas trousers and jumper and blue bonnets with

double ribbons. Before sailing, cannon were loaded, and whenever

the Bails were

set the ships sailed away amidst cheers and the booming of the

cannon, which made the town shake. The cannon used on board for

the whaling were made by the Carron Company, and were about half

the size of the field-piece now mounted in Victoria Park. About

eight months later the return of the sailors was anxiously

looked for, as much by the townspeople as by their own friends.

The first intimation the inhabitants received of their

homecoming was the boom of cannon, which rent the air, as the

whalers sailed up the Firth. The whole population again turned

out to welcome them, and for weeks after their arrival the

sailors entertained their friends and acquaintances with long

stories of their sufferings and hairbreadth escapes on the ice.

We can quite understand that the sailors had to overcome many

hardships, and not the least of these was scurvy. This was

caused by their having to live so long upon salt meat.

There were two boiling-houses in the town, where

the oil was boiled and made ready for sale. Latterly the

principal one was at the top of the Wynd. Many of the whaling

sailors were employed here during the off season. There were two

large copper pans from 15 to 20 fpet long and 12 or 14 feet

broad. These were sunk in the ground, and fired from below. The

blubber was kept at boiling heat, and constantly stirred by two

men until the whole oil was boiled out. It was then run off

through the large taps in each boiler into casks. All refuse was

carted away to the seashore. The men who saw to the tanks and

the boiling of the oil were the harpooners. The boiling-house

was owned by a company of seven gentlemen, some of them local

and some of them from Edinburgh, with John Anderson as its

leading spirit. A great fire occurred in the premises nearly

sixty years ago. No one knew the cause of the outbreak. It was

discovered at nine o'clock at night, and raged with great fury

until midnight. As it happened, there was a large quantity of

oil in barrels in the building. At considerable risk a good many

of these were rolled out into the Wynd and through into the

manse grounds by the gate opposite. The burning oil streamed

down the Wynd, and caused much consternation. Nothing could be

done to save the place, as there was no water available. Indeed,

at this time it could scarcely be had for domestic purposes. The

premises were gutted, but were shortly afterwards reconstructed

on similar lines. A new copper boiler, 12 feet by 6 feet, was

fitted up in the north-west corner of the building, and several

cast-metal coolers put in on the north side. Whaling, however,

soon came to prove unremunerative, and was given up by Mr.

Anderson. The "Jean" was turned into a merchant trader, and was

lost in the Baltic; and shortly after Mr. Anderson's death, in

September, 1870, the plant and furnishings at the boiling-house

were sold by auction.

V.

As already stated, the indefatigable Dr. Roebuck,

in the year 1784, established the pottery in which for the next

century was conducted one of the most important local

industries. This gave Bo'ness a very wide reputation for the

manufacture of many useful kinds of pottery ware, and it also

created a new ciass of workers in the town. The manufacture of

hardware is still continued on an extensive scale in two large

new potteries in Grangepans. But the old Bo'ness Pottery, with

which we are now to deal, was finally closed, and the works sold

fourteen years ago. The pottery passed through the hands of a

number of proprietors after Dr. Roebuck. Among these were Shaw &

Son, with Robert Sym as managing partner; the Cummings, James

Jamieson & Co., and latterly John Marshall <fc Co. A hundred

years ago it employed forty persons, including men, boys, and

girls. The clay for the stoneware was imported from Devonshire,

but the clay for the earthenware was found in the parish. Cream-coloured

and white stoneware, plain and painted and brown earthenware

were the articles principally manufactured. Seventy years ago

the buildings consisted of two kilns on the south side of the

Main Street and two on the north. These employed from eight to

ten kilnmen. The pottery buildings and kilns occupied all the

available space on the north, for the tide then came far up into

what is now reclaimed ground. In Mr. Jamieson's time the

business was greatly extended, and printers and transferers*

were imported from Staffordshire. On his death the business was

found to be insolvent, and the Redding Coal Company, who were

the principal creditors, took possession for a time. Ultimately

a settlement was arranged, and the works were sold to Mr.

Marshall, who retained the old manager. Under the new proprietor

the business flourished. Ground was rapidly reclaimed, the

material for this purpose being carted from the Schoolyard pit.

As the ground was filled in, kilns and workshops were added. Mr.

Marshall was enterprising, and introduced machinery in every

department. Almost every variety of stone and earthenware was

now manufactured.

The potters in the days of the Cummings were less

respectable in character than what they afterwards became. They

had not much reputation for good behaviour and sobriety, as is

illustrated by the following story: —A deformed woman, belonging

to the town, was unfortunate in not getting a husband, and her

somewhat chastened solace on the subject was, "I daursay I'll

just hae tae tak' a potter yet." Drinking bouts were frequent

within the premises, and at times the main gate had to be locked

to prevent drink being taken in. This led to strategy on the

part of the potters within. Sometimes, with the aid of

accomplices outside, bottles were pulled up to the windows by

cords. At others it was smuggled in in a water can. The pottery

boys also were often despatched for liquor in many a secret and

curious way. But this debauchery was in time rooted out of the

works. Mr. Marshall did everything in his power to encourage

intellectual and moral culture in his workpeople. As an evidence

of this he gave his support to a reading-room and other

facilities for the cultivation of the mind. This was established

in the house of William Cummings, and was confined to potters.

It was carried on for many years with great success. The

contribution was one penny per week. Mr. Marshall assumed

William M'Nay as a partner, and he likewise took a keen interest

both in work and workpeople. The place therefore continued to

prosper for many years. At length its trade sadly declined, and

the works were ultimately closed.

The potters formed a conspicuous part of the

Annual Fair Procession of a past generation, and even down to

thirty years ago. The men made a fine display, dressed in white

trousers, white apron tied with blue ribbon, and black coat and

tall hat. They carried specimens of their ware in the shape of

model ships and model kilns, and there was also a brave display

of Union Jacks and ships' flags. The first passenger train to

leave the town, more than fifty years ago, it is noteworthy,

carried the potters on their first excursion.

In the Scottish Exhibition, Glasgow, of 1911,

several specimens of the ware manufactured in Bo'ness Pottery in

its early days were on view.

VI.

During the eighteenth century a soapwork and two

considerable manufactories for dressing flax flourished in the

town. They are defunct long ago. The soapwork waa situated in

the vicinity of the present Albert Buildings. It was owned by

John Taylor, who was known as "Saepy Taylor." It employed six

men, and paid annually to the Government about £3000 in duty.

For the first fifty or sixty years of the same century

Borrowstounness was a great mart for Dutch goods of all kinds,

particularly flax and flax seed. Very large quantities were

imported both for dressing and selling rough. But as the

manufactures of this country advanced so as to increase the

demand for Dutch flax, the traders and manufacturers in other

places imported direct into their own ports, and in consequence

the trade here declined.

What we believe was the first of the many

ironfoundries to be found in the town in the nineteenth century

was started about the year 1836. It was originally carried on

under the firm-name of Steele, Miller & Company, and afterwards

came to be known as the Bo'ness Foundry Company, which is still

its designation. The founder of the firm was Robert Steele, who

prior to settling in Bo'ness was a traveller for the Shotts Iron

Company. Miller was a moulder to trade, and he was assisted in

the practical work by James Shaw. It also gave employment to

several other workmen, and for many years a considerable

business was carried on.

At the east end of the town there existed about

the same time an extensive bonded woodyard, as well as an open

woodyard on the Links. Connected with them, and driven by steam,

was a sawmill containing both circular and vertical saws, and a

very ingenious and efficient planing machine. The same steam

engine moved machinery for preparing bone manure. This sawmill

and woodyard are still in existence, but on a much larger scale.

On the south side of the Links there was also a rope work on a

small scale, but the ropemaking was abandoned over twenty years

ago.

The Bo'ness Distillery, at the west end of the

town, has been in existence for nearly a century. Writing in

1845, the Rev. Mr. M'Kenzie described it as an extensive

establishment even then. The revenue paid to Government, he

says, including malt duty, was sometimes considerably over £300

per week. It was at that time working on a limited scale,

producing only spirit of superior quality. For a time it was

owned by the firm of Tod, Padon & Yannan, and afterwards by A. &

R. Vannan. In 1874 it was purchased from them by James Oalder.

It is now the property of James Calder & Co., Limited, and with

its attendant manufactories of by-products is a very large

concern indeed. We learn from recent figures that there is a

weekly output of 50 tons of yeast, 25,000 gallons of spirits,

and 300 tons of grains for cattle feeding; also that the duty

last year on the firm's production amounted to £1,000,000

sterling.

With the collapse of the local canal scheme the

seaport fell on evil times. The return of better days, however,

was heralded in 1843 by the starting of Kinneil furnaces by John

Wilson of Dundy van. He was an ironmaster of repute in the west,

and his proposal to exploit the ironstone in this district was

hailed with delight. Had Dr. Roebuck but realised the value of

these seams when he was lessee of the colliery he might have

been saved all his financial troubles and losses. The furnaces

were four in number, and were situated on the high ground about

a mile west from the town. For many years, when in full swing,

they were a commanding feature in the landscape, especially in

the night. The iron at that time was melted with the hot-air

process, and the tops of the furnaces were open. Great columns

of flame sprang towards the heavens, lighting up the Firth and

the surrounding district for miles. Bo'ness was then poorly

lighted, and it is said that the glare materially assisted to

illumine the dark places of the town.

Mr. Wilson, who when here lived in the Dean, had

the reputation of being an excellent business man and most

approachable. He was a Liberal in politics, and contested the

county against Lord Lincoln, the Conservative. Wilson was no

speaker, but the election was keenly fought, and he only lost

the seat by seven votes.

One of the managers for John Wilson & Co. at

Kinneil was Mr. John Begg, a grand-nephew of the poet Burns. He

lived at the Dean for many years, and took an active share in

the government of the town. After his death, in 1878, the

manufacture of coke was established on an extensive scale.

Eventually the ironworks were closed down, and have since fallen

into decay. The remains of the furnaces and coke ovens are still

to be seen. It should be stated that the erection of the

furnaces led to the building of the Snab or Kinneil Rows for the

accommodation of the miners and other workers employed. This

contract was in the hands of James Brand, and its execution

caused considerable stir about the place in several employments.

The Newtown Rows on the Linlithgow Road were also built about

the same time, largely by William Donaldson, mason. Another

thing connected, in a sense, with the furnaces was the

institution of Kinneil Reed Band on the 30th of June, 1858, the

inaugural meeting being held in the Old Schoolroom at Newtown.

All the members were connected with Mr. Wilson's ironworks,

hence the reason of the name. On the roll of original members

were eight of the name of Sneddon, six Robertsons, two Grants,

and two Campbells. On Christmas Eve, 1858, in response to an

invitation from Captain William Wilson, the band proceeded to

his residence at the Dean. They played in their best style, and

the captain expressed himself as highly pleased with their

performance, and entertained them to supper. Bo'ness and

Carriden Band was instituted in the same year. Its members,

again, were mostly connected with the Grange Colliery. This band

has made a great name for itself, and has perhaps been more

conspicuously successful as a musical combination than any band

in Scotland.

there was abundance of work for the carting

contractor driving the parrot coal from the pits to the quay and

the iron from the furnaces. The iron was known to be carted to

the quay at as low a charge as 9d. per ton, although the

ordinary rate-was Is. It was shipped to the Continent. The

leading carters in the town at that time where William Kinloch,

the-Edinburgh carrier, and James Johnston, the Glasgow carrier,

and James Gray. Thomas Thomson and his father, in-Grangepans,

also did a large share of that work, and, while-the Thomsons had

the honour of carting away the first pig-iron turned out at

Kinneil, their principal work was in carting the barley which

arrived by boat from the north for the distilleries of Glenmavis,

at Bathgate, and of St. Magdalen at Linlithgow. They also carted

stones to Linlithgow Bridge from Bo'ness for the formation of

the arches in the viaduct there prior to the opening of the

Edinburgh and Glasgow railway. The Bo'ness Pottery also afforded

them considerable trade. Most of the ware there manufactured was

carted' to Edinburgh. On the return journey the carts brought

back rags, which were used for chemical purposes by Robert W.

Hughes in what was known as the Secret Work at the Links.

Allied to the carting trade is the subject of the

tolls and' toll bars. There was supposed to be a distance of six

miles-between each toll, but the miles appear to have been short

in-those days. To begin with, there was the Carriden toll at the

foot of the brae, where the toll-house can still be seen. The

next was on the Queensferry Road at the Binns west gate, and

known as the Merrilees toll. Further east was the-Hopetoun Wood

toll, just at the present hamlet of Woodend. At Kirkliston there

was another, and going west towards; Linlithgow was the

Maitlands toll at St. Magdalen's Distillery. On the Linlithgow

and Queensferry Road was the Boroughmuir toll, and on the road

between Linlithgow and Bo'ness was the-Borrowstoun toll. An

important toll in the west was the Snab toll, which was situated

a few yards to the east of the present entrance to Snab House.

These tolls were under the control of the Justices and

Commissioners of Supply for-the county. They were put up to

auction every year, and knocked down to the highest bidder. Many

of the tolls were licensed, which raised their value, and as

high as £500 has been known to be given for the lease of one of

them for a year. Borrowstoun toll was licensed, and the thirsty

Newtown miners had methods of their own for getting a supply

there early on the Sunday mornings. This and the Snab toll were

the two best in the district. They always let at the highest

rates, because the traffic through them was exceptionally heavy.

Merchandise for the west all went towards Grangemouth for

shipment through the Forth and Clyde Canal. In addition, the

farm traffic was considerable. After the opening of the

Edinburgh and Glasgow railway a big traffic was done to and from

Bo'ness by way of Borrowstoun toll. The receipts from the tolls

must have yielded large sums, as the tariffs were fairly high. A

scale of charges was approved by the Justices, and exhibited at

each toll bar. The keeper could not demand more than the

stipulated rates, but was free to make special terms, and take

less from regular customers. The approved scale exacted 6d. for

a horse and loaded cart. If the cart returned empty no further

charge was made, but if loaded the sixpence •charge was again

imposed. One of the lessees of Borrowstoun toll was a Waterloo

veteran, named James Bruce. He was badly wounded in the battle,

and lay on the plains of Waterloo for three days and three

nights. At length he was picked up and cared for, and although

he had been frightfully slashed about the shoulders and other

parts of his body by the swords •of the Frenchmen, he ultimately

recovered, and was able to return to this country. He also got a

bullet in his arm, which was extracted after his death, and kept

as a curiosity by his son. Bruce kept the toll at Borrowstoun

for a long time, coming there from the Woodside toll, on the

Bathgate Road. The tolls were abolished on the passing of the

Roads and Bridges Act in 1878.

VIII.

Only very fragmentary information can be recorded

concerning the educational affairs of the district. Had it

embraced a University or even a Burgh or Grammar School8"

there would doubtless have been much of interest to relate. As

it is, we are confined to four kinds of schools—the Kirk Session

Schools, the Parish Schools under the Act of 1803, the Private

Schools, and the Secession Schools. The old Parish School of

Carriden was situated at the Muirhouses, the title to it being

dated 1636. In 1804 we find one Alexander Bisset referred to as

the schoolmaster at Carriden, and twelve years later there are

references to Samuel Dalrymple as the schoolmaster. There must

have been others prior to these, but we have not traced them. We

have seen6 the

record of a meeting held at Carriden on the 7th May, 1829, for

the purpose of fixing the schoolmaster's salary, in terms of the

statute, for the twenty-five years following Martinmas, 1828. It

was then resolved that the salary should be the maximum one (£34

4s. 4d.), with the allowance of two bolls of meal in lieu of a

garden until such should be provided for him. At the same time

it was; agreed that the school fees be as follows : —

For Reading English, - - 2s. 6d. per quarter.

For English and Writing, - 3s. per quarter.

For English, Writing, and Arithmetic, - - - 3s. 6d. per quarter.

For Reading English, Writing. Arithmetic, and English Grammar, -

- - 4s. per quarter.

For Latin, along with the other branches above mentioned, 5s.

per quarter.

And for any higher branches of education the fees

were to be according to agreement between the teacher and

pupils.

The last of the old parish schoolmasters was Adam

B. Dorward. He was an excellent teacher, and during his later

years served under the School Board in the new school near

Carriden toll. Half a century ago the first wife of Admiral Sir

James Hope established a school in what is now known as the West

Lodge at Carriden. This was successfully •conducted for many

years. In paragraphs ten and eleven of •our first Appendix will

be found some interesting information by Mr. Dundas about the "pettie"

or private schools in •Carriden. We are in a position to

supplement these somewhat. A school which occupied an important

place in Carriden from the early part of last century onwards

was the Grange Works cSchool. Most of the children connected

with the Grange Colliery and saltworks were sent here, the

school fees being deducted from the wages of the employees. This

school was .situated on the north side of the Main Street near

the east end of Grangepans. The building is still standing, and

is yet known as the Old School. A salt girnel or cellar occupied

the ground floor. The whole of the second floor was utilised .as

a schoolroom; and the top storey was used as the schoolmaster's

house. One of the early schoolmasters here was a Mr. Blair, who

prior to coming to Grangepans had been in .service at Hopetoun

House. His school was attended by nearly one hundred scholars,

and his advanced pupils assisted him in teaching the younger

children. Blair was succeeded by a weaver from Bathgate named

Wardrop. But the most •eminent of all the masters in that school

was Thomas Dickson, who in his early years had been educated for

the ministry. He was painstaking and conscientious, and his

abilities attracted to the Grangepans School many of the

children of the well-to-do merchants in Bo'ness. Many of his

pupils .achieved great success in after life, and several of

them followed in his steps professionally. Among these were

William Wallace Dunlop, who became headmaster of Daniel

Stewart's College, Edinburgh; the late Alexander Shand, the

successor •of the second John Stephens, Bo'ness, and afterwards

one of the Established Church ministers of Greenock; and William

Anderson, late Rector of Dumbarton Academy.

IX.

With regard to Borrowstounness there were five

schools in the town and parish in 1796, and all well attended.

The parish schoolmaster commonly employed an assistant, and had

generally from eighty to ninety scholars. He had a salary of 200

merks Scots (£11 2s, 2fd.), besides the perquisites of his

office as session clerk. The fees then paid were—

English and Writing, per quarter, - - £0 2 6

Latin or French,.....0 5 0

Arithmetic and other branches of Mathematics, ......036

Navigation or Book-keeping, per course, - 1 1 0

We find that on 7th November, 1803,8 the

amount of schoolmaster's salary in Bo'ness Parish was fixed at

400 merks Scots per annum, and that was to continue to be the

salary payable for and during the period of twenty-five years,

from and after the passing of the Act.

It was at same time determined that a commodious

house for a school be provided, with a dwelling-house for the

residence of the schoolmaster, and a portion of ground for a

garden. A scale of fees was likewise fixed at this meeting. This

minute was subscribed by Dr. Rennie, the minister, before these

witnesses—George Hart, shipbuilder, and John Taylor, baker, in

Bor-ness.

This school was, we understand, the first in the

Presbytery built under the 1803 Act. It was erected at what is

now known as George Place, and contained more than the legal

accommodation. The schoolrooms were on the ground floor, and the

schoolmaster's house, which had a separate entrance to the west,

was upstairs. The garden ground was rather deficient in size,

and an equivalent in money was given. So far as we can gather,

John Stephens, who had been schoolmaster under the old system,

was retained under the new Act, and his whole service extended

over a period of fifty years.

In December, 1808, Mr. Stephens petitioned the

heritor and minister, pointing out that the fees fixed in

November, 1803, were " too low in general, and not equal to the

fees paid in almost every town in Scotland." He therefore

requested that they be' increased and made more in keeping with

those towns of "similar size and respectability over the

kingdom," and the request was acceded to. The following are the

scales of 1803 and 1809 : —

|

5—English, per quarter |

2s. |

6d. |

|

English and Writing, per quarter |

3s. |

6d. |

|

English, English Grammar, and Writing

per quarter |

4s. |

|

|

Arithmetic, per quarter |

5s. |

|

|

Arithmetic and English Grammar, per

quarter |

5s. |

6d. |

|

Practical Mathematics, per agreement. |

|

|

|

Book-keeping |

a guinea |

|

Latin, per quarter |

6s. |

|

|

French, per quarter |

6s. |

|

|

1—English Reading, per quarter |

3s. |

6d. |

|

English and Writing |

4s. |

6d. |

|

English Grammar and Writing |

5s. |

|

|

Arithmetic, with English Grammar and

Writing, per quarter, ... |

6s. |

|

|

Latin and Greek, per quarter |

7s. |

|

|

Practical Mathematics, per quarter |

7s. |

6d. |

|

Book-keeping, per quarter |

7s. |

6d. |

In 1845 there were ten schools in the parish,

only one of which was a parochial school. The others we will

refer to later. Early this year Mr. Stephens died, and in March

John Stephens, his son, then parochial schoolmaster in East

Kilbride, was appointed as his successor. He died in 1865, and

on 19th April Alexander Shand, then a teacher in Newington

Academy, was elected to the vacancy. His father was cashier at

Kinneil, and he himself, as we have seen, was educated at Mr.

Dickson's school in Grangepans. Mr. Shand resigned in 1868 to

prosecute his studies for the ministry. Among the favoured

applicants; for the position at this time were William Thomson

Brown,.

Hector of the Grammar School, Dunfermline, and

Adam B. Dorward, Carriden. Mr. Brown was finally chosen, and at

the time of his retiral, upwards of twenty years ago, was

headmaster of Bo'ness Public School. Among the masters of the

many private schools were James Adams, who taught in the Big

House at Newtown, and John Arnot, whose premises occupied the

site of the present Infant School. Arnot taught navigation, and

many of his pupils became captains in the merchant service.

One of the local teachers of this period achieved

an unenviable notoriety. We refer to Henry Gudge, whose school

was situated at the rear of the present Co-operative Store in

South Street. The story of his downfall is well known to the

older generation. He lived in Corbiehall, where he had some

property, which, it is said, was transferred to John Anderson in

settlement of some debt. Gudge became despondent over the

transaction and intemperate in his habits. He worked himself

into the belief that he had been wronged, and decided to have

his money back. There was no bank in Bo'ness then, and he knew

that Mr. Anderson was in the habit of sending money to Falkirk

by a boy who was Gudge's nephew. One Saturday the dominie lay in

wait for the boy about a mile and a half from Bo'ness, and, on

meeting him, directed his attention to a hare in a field. While

the boy went in chase of the hare, real or imaginary, Gudge got

possession of the money bag, containing about £300, and

absconded to Edinburgh. Mr. Anderson offered a reward of £25 for

information leading to the arrest of Gudge. The advertisement

was seen by a girl living in Edinburgh, who was a native of

Grangepans, and had attended Gudge's school. She kept her eyes

open, and one day saw him enter a public-house in Bristo Street,

and informed Detective M'Levy. M'Levy-took Gudge into custody,

and found £180 of the money concealed in three ginger beer

bottles found in his pockets. Gudge was transported to Tasmania

for twenty years. Towards the expiry of the period he showed a

desire, from letters which

came to Bo'ness, to return to his native country,

but he died in Van Diemen's Land in 1859.

We should mention that in 1845 there was a school

at the farm town of Upper Kinneil, supported by the tenantry,

for the convenience of children in the barony. The schoolmaster

got a small salary, and the Duke provided him with a schoolhouse

so that he might make his school fees moderate. About this

period the teacher was James Rutherford, a big man, but very

lame. He was a good, all-round scholar, and was often employed

in land measuring. Among other things he taught basketmaking.

The reeds and willows were gathered in the district by the

pupils, many of whom became expert basketmakers.

The Dissenters supported a school for many years.

This and the other schools in the town were not endowed, and

many of them were taught by females.

X.

Both in Bo'ness and Carriden the care of the poor

was a subject which received most sympathetic and generous

treatment. Even at the present day it could not be more

carefully and usefully handled. We need make no reference to the

administration of the poor funds in Carriden, for that is done

very fully by Mr. Dundas.8 The

minutes of Carriden heritors also, it should be said, contain

most carefully compiled lists of the poor there, and full annual

statements of poor funds. In Bo'ness the poor were numerous. The

funds for their support included weekly collections at the

church door, rent of property purchased with poor funds saved,

the interest of legacies, and mortcloth dues. The amount

received from the last was trifling, because the county

parishioners and the different corporations in the town, such as

the Sailors and Maltmen, kept mortcloths of their own, and

received the emoluments. In 1796 the pensioners who got regular

supply numbered thirty-six. Occasional supplies upon proper

recommendations were often granted to such persons as were

reduced to temporary distress. Upon any pressing emergency,

wrote Dr. Rennie, the liberality of the opulent part of the

inhabitants was exemplary. These people, he also says, were

well-bred, hospitable, and public-spirited.

A severe winter was experienced about 1795, and

nearly £60 sterling was collected and distributed in a most

judicious manner by a committee of gentlemen in the town.

Begging was oommon, but it was explained that the paupers who

went about from house to house were, for the most part, from

other parishes. We have elsewhere referred to the method of

managing the poor funds of Kinneil. The average receipts and

expenditure of the poor funds for Bo'ness for the three years

ending 1837 were as follows:—Income—Church door collections, £45

2s. 6d.; rent of landed property, £32 8s.; interest of bond,

legacy, mortcloth dues, and proclamations, £37 18s. 7d.; total,

£115 9a. Id. The total expenditure, however, came to £225 0s.

Id., and the deficiency of £109 lis. had to be made up by the

Duke of Hamilton. There was in 1845, and still is, we believe,

an association of ladies for the purpose of supplying the poor

with clothes, meal, and coals in the winter. The farmers

generously aided in this work by carting the coals gratuitously.

There was also a Bible and Education Society, in the support and

management of which Churchmen and Dissenters united. From its

annual contributions about twenty-five poor children received a

plain education. And the Scriptures, the Shorter Catechism, and

school books were supplied to the poor gratuitously or at

reduced prices.

The whole interesting history of the poor funds

of Bo'ness was recently reviewed in an action of declarator at

the instance of the Parish Council,9 and

as a result the body now known as Bo'ness Parish Trust was

formed.

We now refer to a more gruesome subject. Until

some twenty years ago there stood at the gate of the South

Churchyard, at the Wynd, a small watch-house. This was used for

the purpose of sheltering the watchmen during the raids of the "Resurrectionists"

in the first quarter of last century, when corpses were stolen

for anatomical and other purposes. Every householder had to take

his turn in the watch-house, or find a substitute. It was usual

to watch for at least a sufficient time for the body to be

considerably decomposed. Some of the local worthies made a

profession of watching, and they were paid for their services at

the rate of Is. per night. In addition, parties employing them

invariably provided bread and porter for supper. It was no

unusual thing therefore for miners on their way to work in the

early morning to find certain of these watchers hanging over the

churchyard wall suffering from a more potent influence than the

want of sleep.

XI.

There were two serious outbreaks of cholera here

last century. The first occurred in 1831, and the second about

twenty years later. The second outbreak was especially deadly,

and it was not an unusual thing to meet a friend in good health

the previous night and to learn of his or her death the

following morning. Many well-known people of that day had fatal

seizures. These included Mrs. Hill, wife of Mr. George Hill,

watchmaker; Mrs. Campbell, of the Green Tree Tavern; Robert

Grimstone, her brother; Matthew Faulds, West Bog; and Peter

Thom, of the East Bog. We understand the churchyard on the shore

at Corbiehall was necessitated because of the havoc which this

outbreak caused among the inhabitants.

We have not seen any records bearing on these

outbreaks so far as concerns Bo'ness. One of the minute books of

the heritors of Carriden, however, contains the "Minutes of the

proceedings of the Board of Health instituted in the Parish of

Carriden to adopt precautionary measures against the threatened

invasion of the pestilential disease, usually denominated

Asiatic or epidemic cholera morbus." The first of these is dated

Carriden

Church, 20th December, 1831, and contains this

introduction— "A disease of the most malignant description, and

formerly unknown in Europe, originating in Asia, and taking its

course through Russia and other countries in a westerly

direction, having begun to make its ravages in some of the

southern parts of our island, a public meeting of the

inhabitants of the parish was called on the previous Sabbath

from the pulpit to adopt measures for the purpose of preventing,

if possible, by human means, the communication of such disease

by infection, and of mitigating its virulence if, unfortunately,

the malady should come among us."

A local Board of Health was then instituted,

having Mr. James John Cadell of Grange as president and the Rev.

David Fleming as secretary. Power was given them to convene the

Board as circumstances required. Mr. Fleming stated that, in

consequence of an urgent recommendation which he had felt it to

be his duty to give the people from the pulpit, a good deal of

attention had been paid by them to the cleaning, whitewashing,

and ventilating of their houses. He also read an extract from a

letter from Mr. James Hope of Carriden, then in London,

recommending the instant adoption of strong measures to ward

off, if possible, the threatened evil. Mr. Hope had sent the sum

of £20 for the purpose of providing warm clothing for the poor,

and this the minister had been endeavouring to disburse to the

best of his judgment. The parish was then divided into seven

districts, each under the inspection of three or four persons.

The following rules were adopted as instructions

to the inspectors, and recommended to be duly enforced by them

upon the parishioners: —

1.

No private dunghills to be allowed nearer the dwelling-house

than 12 feet.

2. All pigstyes to be removed from

dwelling-houses to a

convenient distance, and to be kept regularly

clean.

3. All rabbits to be removed from

dwelling-houses, and all other animals to be recommended to be

removed,

except the usual domestic animals, such as dogs

and cats.

4. All dung to be removed when equal in quantity

to a cart-load, and all householders to clear once a week

immediately before their own dwellings.

5. The inspectors to meet in a week to give in

their report, and thereafter the Board to meet once a fortnight

on Tuesdays in the Session-house at twelve o'clock noon.

On the 27th December the inspectors reported, for

the most part, that everything was "in a tolerable condition of

cleanliness, with the exception of John Black's keeping a sow."

This he was required to remove. Dr. Cowan reported that the

fever was abating, but the inspectors were urged to continue

their efforts to remove all existing nuisances. Subscriptions to

the amount of £54 are detailed in February, 1832, and lists of

those relieved. The quantities of flannel and blankets, meal and

potatoes given out are also detailed from time to time.

Towards the end of the year the dread disease was

greatly mitigated. This, in a great measure, was due to the

excellent services of Dr. Cowan and to the thorough methods of

the local Health Board.

When the disease was stamped out the doctor

submitted an interesting tabular view of all the cases, giving

name, age, date of the seizure, date of death or recovery. In it

we find the smallest number of hours from time of seizure till

death, 11; greatest, 95; average, 33. He also stated that the

patients who died were all, with one exception, in a state of

collapse, no pulsation of the heart being perceptible. The

exception was not in a state of collapse—the patient had

recovered, but rose too soon, and this caused a fatal return of

the malady.

We have not observed any record of the second

outbreak having extended to Carriden. As we have said, it was

very bad in Bo'ness, so more than likely Carriden was seriously

affected also.

XII.

In modern days the important subject of foreshore

reclamation is at last receiving great attention. Here, however,

we had a practical illustration of it on Kinneil estate in the

time of the first Lord Hamilton, who, as we have seen, made

extensive reclamations from 1474 onwards. Mr. Cadell in his

recent work13 evidently

unconsciously refers to these when he says—"A portion of the

Carse of Kinneil, on the Duke of Hamilton's estate, has been

reclaimed long ago by a low dyke faced on the outside with

stone. The land inside the bank is a few feet below the level of

high water at spring tides; but this is a very old intake, the

record of which I have not been able to discover." Reference to

his foreshore reclamation map confirms our impression. Those who

wish to study this very practical and far-reaching subject will

find the whole matter fully discussed in two of Mr. Cadell's

chapters. The methods employed in his own extensive reclamations

are also described. We can do no more here than quote what was

written on the subject to the two Statistical Accounts in 1796

and 1845 respectively.

Dr. Rennie states—" It is highly probable that

all the low ground in the parish was formerly part of the bed of

the river Forth. This opinion easily gains assent, because

immediately at the bottom of the bank, far from the shore, and

far above the level of the present spring tides, shells,

particularly oyster shells, are to be seen in several places in

great quantities. At low water, above two thousand acres,

opposite to the parish, are left dry. It is said that a Dutch

company offered for a lease of ninety-nine years to fence off

the sea from the acres with a dyke to prepare them for the

purposes of agriculture, which would have been a vast accession

to the carse grounds of the parish. But the project failed, and

a large extent of ground remains useless, showing its faoe twice

every twenty-four hours to reproach the fastidiousness and

indolence of mankind." Mr. M'Kenzie referred to the same subject

thus—" Between Bo'ness harbour and the mouth of the Avon about

one thousand acres of a muddy surface are exposed at low water.

These, if reclaimed from the sea for agricultural purposes,

would be a valuable addition to the Carse of Kinneil. This part

of the frith' is becoming shallower, owing to the accumulation

of mud brought down by the Avon and Carron, and especially by

the Forth, and the beach is assuming more of a fluviatic

character. Sir Robert Sibbald says, 'These shallows have the

name of the Lady's Scaup.' The Dutch did offer some time ago to

make all that scaup good arable ground and meadow, and to make

harbours and towns there in convenient places upon certain

conditions, which were not accepted."

Towards the end of the year 1859 the inhabitants

of Borrowstounness were summoned by tuck of drum to assemble at

the Old Town Hall to take into consideration the formation of a

company of Volunteers. Captain William Wilson, of Kinneil, a son

of Mr. John Wilson, and a captain in the 2nd Lanark Militia, was

called upon to preside. On the platform with him were the Rev.

Kenneth M'Kenzie, Provost Hardie, Linlithgow; John Vannan,

distiller; John Stephens secundus, parish schoolmaster; Patrick

Turnbull, factor to the Duke of Hamilton; John Begg, manager,

Kinneil; and Dr. Murray. The Rev. Mr. M'Kenzie, who sported a

scarlet vest as a badge of patriotism, delivered a powerful

oration on the duties of the citizens of a free country,

concluding with a stirring appeal to come forward at once and

enrol. As a result of this no fewer than one hundred patriotic

and sturdy fellows from Bo'ness and Carriden enrolled before the

meeting was closed. The swearing-in of the company took place at

Kinneil House on 1st June, 1860. Sheriff Kay officiated, and was

accompanied by many of the gentry of the county. The day was

observed as a holiday in BoJness, and crowds of people assembled

to witness the interesting ceremony. As showing the enthusiasm

of the members it need only be said that those whose occupations

prevented them from attending drill in the evenings turned out

at five o'clock in the morning. At that period the Government

did nothing except supply the rifles. The county gentlemen came

to the rescue, and paid for the accoutrements. The salary of the

drill instructor had to be paid by the members of the company,

who had to bear the cost of their own uniforms besides. The

price of each uniform wras £2 15s.

This and the 10s. 6d. per man for the instructor the Volunteers

bore cheerfully. Latterly the Government became alive to their

duty, and increased their grant. But it was not until they made

the full grant that drill went on in a proper way and the

interest increased.

A memorable event in the history of the Volunteer

movement was the great Scottish Review of 7th August, 1860, in

which 122,000 Volunteers took part in Holyrood Park. The Bo'ness

men were taken by steamer to Leith, and marched up to Lochrin,

where they were attached to the Breadalbane Highlanders.

Among the few who now remain of the originally

enrolled company are Captain William Miller, V.D., and Corporal

James Paris.

When Borowstounness began to officially adopt a

seal and motto we have not precisely ascertained. It is almost

certain, however, that it was not much more than fifty years

ago. They are described by the late Marquis of Bute —

On the waves of the sea a three-masted ship in

full sail to sinister.

The seal on which these arms appear is in a

general way taken from that of the Seabox Society. When both are

closely examined, however, a number of differences are seen. The

society's seal has the three-masted ship on the waves and turned

to sinister, but the sails are in this case furled. There is

also in

chief a lion rampant,

which latter upon the old bell of the society, dated 1647, is

represented as passant. The

origin of the lion cannot be satisfactorily accounted for. As

for the motto, "Sine

metu,"

this, again, is a departure from that of the Seabox Society,

which was, as we have elsewhere stated, "Verbum

Domini manet in (sternum." |

|