Philip Doddridge, the famous divine and

hymn-writer, was on terms of the closest intimacy with Gardiner,

and about two years after Prestonpans he wrote Gardiner's

biography. There he gives a vivid and lengthened account of his

friend's spiritual experiences. Jupiter Carlyle, also, in his

autobiography gives frequent glimpses of him. Thus abundant

material is at the disposal of any one who wishes to make the

acquaintance of this brave and pious soldier. Doddridge is

evidently in doubt as to the year of his birth, as he gives

1687-8, but the tablet at Carriden has 1687.

Gardiner's father was Captain Patrick Gardiner,3 of

the family of Torwood Head, and his mother Mary Hodge, of the

family of Gladsmuir. The Captain served in the Army in the time

of William and Queen Anne, and died with the British foroes in

Germany shortly after the battle of Hochset.

The son, afterwards Colonel Gardiner, was

educated at the "Grammar School of Linlithgow. He served as a

cadet very early, and at fourteen years of age obtained an

ensign's commission in a Scots regiment in the Dutch service, in

which he continued till 1702, when he received an ensign's

commission from Queen Anne. At the battle of Ramillies, where he

specially distinguished himself, he was wounded and taken

prisoner, but was soon after exchanged. We are told that at this

battle, while calling to his men to advance, a bullet passed

into his mouth, which, without beating out any of his teeth or

touching the forepart of his tongue, went through his neck. The

young officer, like so many of the wounded engaged with the Duke

of Marlborough's army, was left on the field unattended, and lay

there all night, not knowing what his fate might be. His

suspicions at first were that he had swallowed the bullet, but

he afterwards made the discovery that there was a hole in the

back of his neck, through which it must have passed. In the

morning the French came to plunder the slain, and one of them

was on the point of applying his sword to the breast of the

young officer when an attendant of the plunderers, taking the

injured lad by his dress for a Frenchman, interposed, and said,

"Do not kill that poor child." He was given some stimulant, and

carried to a convent in the neighbourhood, where he was cured in

a few months. He served with distinction in the other famous

battles fought by the Duke of Marlborough, and rose to the rank

of colonel of a new regiment of Dragoons.

As a young man he was what would now be called

fast; but he was at all times so bright and cheerful that he was

known as the "happy rake." His remarkable conversion occurred

when waiting till twelve o'clock on a Sunday night to keep a

certain appointment. To while away the time he took up a book

which his mother had placed in his portmanteau. This was " The

Christian Soldier; or Heaven Taken by Storm." The result was

that he forgot his appointment, and became converted. Nor was

the change either fanatical or temporary. Gardiner was still as

careful, active, and obedient a soldier as ever, but now he

tried in his private life to avoid even the appearance of evil.

He was specially anxious to appear pleasant and cheerful lest

his associates might be led to think that religion fostered a

gloomy, forbidding, and austere disposition. At the same time,

he set himself sternly against infidelity and licentiousness.

The circumstances connected with Colonel

Gardiner's death at the Battle of Prestonpans are very tragic,

and have been frequently treated in history and fiction. The

brutality connected with his death cannot be excused and

scarcely palliated by the ignorance of his assailants. By all

who knew him—military friend or foe—his death was deplored.

IV.

William Wishart, Twelfth Principal oF the

UniversitY oF Edinburgh, 1716-1729.

Mr. Wishart was a son of the last minister of

Kinneil. There is no available evidence as to date and place of

birth, but it is highly probable that it was Kinneil.4 The

eldest son, afterwards Sir George, entered the Army, and

ultimately acquired the estate of Cliftonhall, Ratho; the next,

afterwards. Sir James, of Little Chelsea, was a Rear-Admiral in

the Royal Navy, and died in 1723; and the third became one of

the ministers of Edinburgh and Principal of the University.

William Wishart5 succeeded

the great William Carstares in the Principalship, and it is

thought that the latter recommended him to the Town Council,

with whom the appointment lay. William graduated at Edinburgh in

1676, and afterwards proceeded to Utrecht to study theology.

Like his father, he had to suffer imprisonment, for on his

return from Holland (1684) he was imprisoned by the Privy

Council in the " Iron House " on the charge of denying the

King's authority. He was released the next year under bond, with

caution of 5000 merks, to appear when called. He then became

minister of South Leith (it will be recalled that his father

also was minister in Leith after the suppression of Kinneil),

and afterwards of the Tron Church. Wishart was five times

Moderator of the General Assembly, and has been described as " a

good, kind, grave, honest, and pious man, a sweet, serious, and

affectionate preacher whose life and conversation being of a

piece with his preaching made almost all who knew him personal

friends." Two volumes of his sermons were published. His career

as Principal seems to have been uneventful.

We may mention here also that on the 10th

November, 1736, the Edinburgh Town Council proceeded to elect to

the fifteenth Principalship William Wishart secundus, son of the

above. The induction, however, was postponed till November of

the next year, a charge of heresy evidently barring the way.

When called to be Principal he also received a call from New

Greyfriars. The Edinburgh Presbytery interposed and objected to

the doctrine of some sermons published by him while minister of

a Dissenting congregation in London, in which he had maintained

"that true religion is influenced by higher motives than

self-love." After a keen debate the General Assembly absolved

Wishart from heresy, and he entered upon his charges. He is said

to have been more of a scholar and man of letters than his

father, and of an original turn of mind, adopting a different

style of preaching from that formerly in vogue. He was less

stiff and formal, dealt more with moral considerations, and used

more simple and, at the same time, more literary language. His

first act as Principal was to start a library fund for the

University. He also made an attempt to improve the system of

graduation in Arts by demanding literary theses from the

"graduates. The Principal took a great interest in the more

promising of the students, constantly visited the junior

classes, and used all means in his power to improve scholarship

in the University.

V.

De. John Roebuck (b. 1718, d. 1794).

John Roebuck was born in Sheffield, where his

father was a manufacturer of cutlery. He possessed a most

inventive turn of mind; studied chemistry and medicine at

Edinburgh; obtained the degree of M.D. from Leyden University in

1742; established a chemical laboratory at Birmingham; invented

methods of refining precious metals and several improvements in

processes for the production of chemicals, including the

manufacture of sulphuric acid, at Prestonpans, in 1749, where he

was in partnership with Mr. Samuel Garbett, another Englishman.

In 1759, he, along with his brothers, Thomas,

Ebenezer, and Benjamin, William Cadell, sen., William Cadell,

jun., and Samuel Garbett, founded the Carron Ironworks, which at

one time were the most celebrated in Europe. - His connection

with Borrowstounness began about the same time when he became

the lessee of the Duke's coal mines and saltpans, and took up

residence at Kinneil House. The history of his partnership with

James Watt, the part which he played in the government •of the

town, and the unfortunate collapse of all his plans are

•elsewhere referred to. In 1773 the doctor, owing to his

financial misfortunes here, had not only to give up his interest

in Watt's patent, but had also to sever his connection with the

Carron Company. His spirit and business enterprise, however,

were undaunted, and, in 1784, we find him founding the Bo'ness

Pottery. He died here in 1794, and was buried in Carriden

Churchyard.

From the various works which he projected, all of

a practical nature; from his generous and kindly treatment of

James Watt, and his keen desire to promote the interests of the

inhabitants of Bo'ness, we readily conclude that, in ability and

real goodness, he was far above the average man. This is

attested by the monument to his memory which his friends erected

over his grave. The inscription is in Latin, but we give below a

translation7—

Underneath this tombstone rests no ordinary man,

John Roebuck, M.D., who, of gentle birth and of liberal

education, applied his mind to almost all the liberal arts.

Though he made the practice of medicine his chief work in his

public capacity to the great advantage of his fellow-citizens,

yet he did not permit his inventive and tireless brain to rest

satisfied with that, but cultivated a great number of recondite

and abstruse sciences, among which were chemistry and

metallurgy. These he expounded and adapted to human needs with a

wonderful fertility of genius and a high degree of painstaking

labour; whence not a few of all those delightful works and

pleasing structures which decorate our world, and by their

utility conduce to both public and private well-being he either

devised or promoted. Of these the magnificent work at the mouth

of the Carron is his own invention.

In extent of friendship and of gentleness he was

surpassing great, and, though harassed by adversity or deluded

by hope and weighed down by so many of our griefs, he yet could

assuage these by his skill in the arts of the muses or in the

delights of the country.

For most learned conversation and gracious

familiarity no other was more welcome or more pleasant on

account of his varied and profound learning, his merry games,

and sparkling wit and humour. And, above all, on account of the

uprightness, benevolence, and good fellowship in his character.

Bewailed by his family and missed by all good

men, he died on the Ides [i.e., 15th]

of July.

a.d.

1794, aged 76, in the arms of his wife, and with his children

around him.

This monument—such as it is—the affection of

friends has erected.

VI.

James Watt (b.

1736, d. 1819).8

The name and fame of this celebrated natural

philosopher and civil engineer are so well known that they

require little mention here. He was born in Greenock, but

Glasgow and Birmingham were the chief centres of his labours.

Bo'ness, however, has a right to claim more than a passing

interest in his early endeavours to improve the steam engine. He

had been struggling as a mathematical instrument maker to the

University of Glasgow when his friend Professor Black spoke of

him to Dr. Roebuck, who was engaged sinking coal pits. Roebuck

had been time and again thwarted in his attempt to reach the

coal by inrushes of water, his Newcomen engine having proved

practically useless. Therefore, when Dr. Black informed him of

this ingenious young mechanic in Glasgow who had invented a

steam engine capable of working with a greater power, speed, and

economy, Roebuck immediately entered into •correspondence with

Watt. Roebuck was at first sceptical as to the principle of

Watt's engine, and induced him to revert to the old principle,

with some modifications. Against his convictions Watt tried a

series of experiments, but abandoned them as hopeless, Roebuck

being also convinced of his error. Up to this time Watt and

Roebuck had not met, but in September, 1765, Roebuck urged him

to come with Dr. Black to Kinneil House and fully discuss the

subject of the engine. Watt wrote to say that he was physically

unable for the journey to Kinneil, but would try to meet him on

a certain day at the works at Carron, in which the doctor had an

interest. Even this, however, had to be postponed. Roebuck then

wrote urging Watt to press forward his invention with all speed,

"whether you pursue it as a philosopher or as a man of

business." In accordance with this urgent appeal, Watt forwarded

to Roebuck the working drawings of a covered cylinder and

piston, to be cast at the Carron Works. This cylinder, however,

when completed, was ill bored, and had to be laid aside as

useless. The piston rod was made in Glasgow, under his own

supervision, and when finished he was afraid to forward it on a

common cart lest the workpeople should see it, .and so it was

sent in a box to Carron in the month of July, 1766.

This secrecy was necessary to prevent his idea

being appropriated by others. Roebuck was so confident of Watt's

success that in 1767 he undertook to give him £1000 to pay the

debts already incurred, to enable Watt to continue his

•experiments, and to patent the engine. Roebuck's return was to

be two-thirds of the property in the invention. Early in 1768

Watt made a new and larger model, with a cylinder of seven or

eight inches diameter, but by an unforeseen misfortune " the

mercury found its way into the cylinder and played the devil

with the solder. This throws us back at least three days, .and

is very vexatious, especially as it happened in spite of the

precaution I had taken to prevent it." Disregarding the renewed

demands of the impatient Roebuck to meet and talk the matter

over, Watt proceeded to patch up his damaged engine. In a

month's time he succeeded, and then rode triumphantly to Kinneil

House, where his words to Roebuck were, "I sincerely wish you

joy of this successful result, and I hope it will make some

return for the obligations I owe you."

The model was so satisfactory that it was at once

determined to take out a patent for the engine, and Watt

journeyed to Berwick, where he obtained a provisional

protection. It had been originally intended to build the engine

in "the little town of Borrowstounness." For the sake of

privacy, however, Watt fixed upon an outhouse in a small

enclosure to the south of Kinneil House, where an abundant

supply of water could be obtained from the Gil burn. The

materials required were brought here from Glasgow and Carron,

and a few workmen were placed at his disposal. The cylinder—of

eighteen inches diameter and five feet stroke—was cast at

Carron. Progress-was slow and the mechanics clumsy. Watt was

occasionally compelled to be absent on other business, and on

his return he usually found the men at a standstill. As the

engine neared completion his anxiety kept him sleepless at

nights, for his fears-were more than equal to his hopes. He was

easily cast down by little obstructions, and especially

discouraged by unforeseen expense. About six months after its

commencement the new engine, on which he had expended so much

labour, anxiety, and ingenuity, was completed. But its success

was far from decided. Watt himself declared it to be a clumsy

job. He was grievously depressed by his want of success, and he

had serious thoughts of giving up the thing altogether. Before

abandoning it, however, the engine was again thoroughly

overhauled, many improvements were effected, and a new trial

made of its powers. But this did not prove more successful than

the earlier one had been. "You cannot conceive," he wrote to

Small, " how mortified I am with this disappointment. It is a

damned thing for a man to have his all hanging by a single

string. If I had the wherewithal to pay the loss, I don't think

I should so much fear a failure; but I cannot bear the thought

of other people becoming losers by my schemes, and I have the

happy disposition of always painting the worst." Bound therefore

by honour not less than by interest, he summoned up his courage

and went on anew. In the principles of his engine he continued

to have confidence, and believed that, could mechanics be found

who would be capable of accurately executing its several parts,

success was certain. By this time Roebuck was becoming

embarrassed with debts and involved in various difficulties. The

pits were drowned with water, which no existing machinery could

pump out, and ruin threatened to overtake him before Watt's

engine could come to his help. The doctor had sunk in his coal

works his own fortune and part of that of his relations, and was

thus unable to defray the expense of taking out the patent and

otherwise fulfilling his engagement with the inventor. In his

distress Watt appealed to Dr. Black for assistance, and a loan

was forthcoming; but, of course, this only left him deeper in

debt, without any clear prospect of ultimate relief. No wonder

that_ he should, after his apparently fruitless labour, have

expressed to Small his belief that, "Of all things in life,

there is nothing more foolish than inventing." The unhappy state

of his mind may be further inferred from his lamentation

expressed in a letter to the same friend on the 31st of January,

1770—"To-day I enter the thirty-fifth year of my life, and I

think I have hardly yet done thirty-five pence worth of good to

the world; but I cannot help it." By the death, also, of his

wife, who cheered him greatly in his labours, an unfortunate

combination of circumstances seemed to overwhelm him. No further

progress had yet been made with his steam engine, which, indeed,

he almost cursed as the cause of his misfortunes. Dr. Roebuck's

embarrassments now reached their climax. He had fought against

the water until he could fight no more, and was at last

delivered into the hands of his creditors, a ruined man. His

share in Watt's invention was then transferred to Matthew

Boulton, of Birmingham.

VII.

This was the turning-point for "Watt. Birmingham

was an excellent trade centre, and within it were to be found

experienced mechanics. The firm of Boulton, Watt & Co. was

formed in 1774, and Watt's success was thenceforward ensured.

Although Roebuck had to give in, there is no

doubt that Watt was so much indebted to him at the beginning

that, without his aid and encouragement, he would never have

gone on. Robinson says, " I remember Mrs. Roebuck remarking one

evening, ' Jamie is a queer lad, and without the doctor his

invention would have been lost, but Dr. Roebuck won't let it

perish.' "

Watt's connection with Kinneil and Bo'ness must

have lasted a number of years. There are many stories concerning

his engines,8 probably

mostly experimental, which were in use at the local pits. These,

no doubt, were in operation, and attained a considerable degree

of success before he removed to Birmingham, but too late to be

of any practical assistance to his partner Roebuck. Of the

engine at Taylor's pit the workmen could only say that it was

the fastest one they ever saw. From its size, and owing to its

being placed in a small timber-house, the colliers called it the

" box bed." The one at the Temple pit was known as Watt's

spinning wheel. The cylinder of his engine at the Schoolyard pit

lay there for many years. It was in the end purchased by Bo'ness

Gas Company, in whose possession it now is. The outhouse at

Kinneil in which Watt constructed his first engine and conducted

his many experiments still remains, but it is in a dilapidated

condition. Undoubtedly Watt's mental endowments were great, but

he was called upon to suffer disappointment after disappointment

and bitter reverses of fortune. His courage, force of character,

and mechanical genius ultimately carried him towards complete

success, so that he retired with a handsome fortune.

VIII.

Dugald Stewart (b.

1753, d. 1828),

Professor of Moral Philosophy in

the Edinburgh University.

After relinquishing the duties of his Chair in

1809 this eminent Scotsman retired to Kinneil House, which his

friend the Duke of Hamilton had placed at his disposal. Here he

spent the twenty remaining years of his life in philosophical

study. From Kinneil he dated his Philosophical

Essays, in

1810, the second volume of the Elements, in

1813; the first part of theDissertation, in

1821, and the second part in 1826; and, finally, in 1828, the Philosophy

of the Active and Moral Powers, a

work which he completed a few weeks before the close of his

life.

Dugald Stewart was born in the precincts of

Edinburgh University, where his father, the Professor of

Mathematics, resided. He studied at the University there, but

after a time was attracted to Glasgow University, like a good

many others, by the fame of Professor Reid, who occupied the

Chair of Moral Philosophy. At the age of nineteen he was

accepted by the Senatus as his father's substitute during the

latter's illness, and returned to Edinburgh. Two years later he

was appointed assistant and successor. With three days'

preparation he, in 1778, undertook the work of the Chair of

Moral Philosophy when Adam Ferguson made his visit to America.

In 1785, the year of his father's death, he exchanged Chairs

with Ferguson. It was a happy exchange for Stewart. He was so

versatile that he could, at a moment's notice, occupy any Chair

in the University, and there is no •doubt that as Professor of

Mathematics he discharged the duties with distinction. But his

reading, his studies, and the natural bent of his mind

peculiarly fitted him to be the popular exponent of Dr. Reid's

commonsense philosophy. His fame became so great that he drew

young men of family and fortune to attend his classes. He was in

the habit of boarding students, and it has been said that

noblemen did not grudge £400 for the privilege of having their

sons admitted to Professor

Stewart's charming home. Among those who attended

his class were the young men who afterwards became Lord

Palmerston, Lord John Russell, Lord Brougham, Lord Cockburn, and

Lord Jeffrey.

Lord Cockburn has left us some very vivid and

sympathetic recollections of Stewart as a lecturer, and of the

influence he exercised over his students. Entrance to Dugald

Stewart's class was, he says, the great era in the progress of

young men's minds. To him his lectures were like the opening of

the heavens. He felt that he had a soul; and the professor's

noble views, unfolded in glorious sentences, elevated him into,

a higher world. Stewart, he affirms, was one of the greatest of

didactic orators, and had he lived in ancient times his memory

would have descended to us as that of one of the finest of the

old eloquent sages. Flourishing, however, in an age which

required all the dignity of morals to counteract the tendencies

of physical pursuits and political convulsions, he had exalted

the character of his country and of his generation. Without

genius or even originality of talent, his intellectual character

was marked by calm thought and great soundness. His training in

mathematics may have corrected the reasoning, but it never

chilled the warmth of his moral demonstrations.

All Stewart's powers were exalted by an

unimpeachable personal character, devotion to the science he

taught, an exquisite taste, an imagination imbued with poetry

and oratory, liberality of opinion, and the highest morality.

His retiral made a deep and melancholy impression on his

students and on all those interested in the welfare of mental

philosophy.

In his earlier years Mr. Stewart had resided at

Catrine House. Catrine, originally the country-house of his

maternal grandfather, and there he met and entertained the poet

Burns. This friendship was renewed on the poet's visit to

Edinburgh.

His biographer has

told us that Mr. Stewart's time at Kinneil was almost

exclusively devoted to his literary labours.

Dugald Stewart.

By permission from "Scottish Men of Letters in

the XVIII. Century" by H. Grey Graham (Black).

He, however, relieved these by friendly

intercourse, and by the calls of those strangers whom the lustre

of his name led to pay a passing visit to Kinneil. Among his

friends was Sir David Wilkie, the painter. He was always in

search of subjects for his pictures, and Mr. Stewart found for

him in an old farmhouse in the neighbourhood the cradle chimney

introduced into the " Penny Wedding." Other friendly visitors at

Kinneil included Lord Palmerston and Earl Russell. A detailed

account of the life and writings of his father, which abounded

in anecdotes and notices of the many distinguished men with whom

he was on terms of intimacy, was prepared by Mr. Stewart's son.

Most unfortunately this memoir and the greater part of the

professor's correspondence and journals were unwittingly

destroyed by the son in a fit of mental aberration brought on by

a sunstroke. Little record, then, is left of his long and

interesting occupancy of Kinneil. In 1822 he was struck with

paralysis. The attack affected his power of utterance and

deprived him of the use of his right hand. Happily, it neither

impaired any of the facilities of his mind nor the

characteristic vigour and activity of his understanding. It,

however, prevented him from using his pen, and Mrs. Stewart

became his amanuensis. From a letter written by her to a friend

in 1824 we find that Mr. Stewart's health was as good as they

could possibly hope after the severe attack three years

previously, and that he walked between two and three hours every

day.

In 1828 Mr. and Mrs. Stewart went to Edinburgh on

a brief visit to their friend Mrs. Lindsay, No. 5 Ainslie Place.

Here Mr. Stewart was seized with a fresh shock of paralysis, and

died on 11th June. He was buried in the Canongate Churchyard. A

monument to his memory, erected by his friends and admirers,

stands upon the Calton Hill.

Mr. Stewart was twice married. His first wife was

Helen, daughter of Neil Bannatyne, Glasgow, and the marriage

took place in 1783, after a long courtship. She died in 1787,

leaving an only child, Matthew, on whom his father centred all

his affections. He in time entered the Army, and rose to

distinction. The professor's second wife was Helen d'Arcy

Cranstoun, third daughter of the Hon. George Cranstoun, youngest

son of William, fifth Lord Cranstoun. This marriage took place

in 1790. Mrs. Stewart, we are told,9 was

a lady of high accomplishments and fascinating manner—uniting

with vivacity and humour depth and tenderness of feeling. She

sympathised warmly with the tastes and pursuits of her husband,

and so great was his regard for her judgment and taste that he

was in the habit of submitting to her criticism whatever he

wrote. Mrs. Stewart also held a high place among the writers of

Scottish song. She died in 1838. There were two children of this

marriage—a son, George, a youth of great promise, whose death,

in 1809, occasioned the deepest affliction to his parents, and

led to Mr. Stewart's retirement from professorial duty—and a

daughter, Maria d'Arcy, who survived her father and mother, and

died in 1846. Miss Stewart was endeared to a very extensive

circle of friends by the charms of a mind of great vigour and

rich culture, manners the most fascinating, and a heart full of

warmth, tenderness, and affection.

Mrs. and Miss Stewart were the last occupants of

Kinneil House, and their departure after the professor's death

was much regretted by every inhabitant of the parish. The active

benevolence of the family was extensive, and was long and

gratefully remembered.

X.

Donald Potter (b.

1756, d. . . . ).

In one of the privately enclosed burial-places

alongside the east wall of the lower churchyard lie the mortal

remains of Donald Potter, captain of the Royal Navy. This is

almost all that can be gathered of this worthy, for the

lettering on the memorial tablet is so eaten away as to be

indecipherable. On the top of the stone-there is still to be

seen a splintered cannon ball hooped with iron. Beneath are

carved a crown and an anchor.

Donald Potter was a native of the parish of

Livingstone, in this county. His father was James Potter, and

his mother Katherine Mitchell. At an early age he joined the

Royal Navy, and by good conduct, gallant deeds, and long and

efficient service rose to an important position. He specially

distinguished himself under Admiral Howe in his crushing defeat

of the French fleet off Brest on the 1st of June, 1794. In

October, 1809, Potter received a commission as lieutenant of His

Majesty's ship the " Bellona," and in February, 1811, was

appointed to the same position on board the "Princess." Much to

his regret he had to retire about 1814, when he settled in

Borrowstounness, where he had some relatives. Upon the

mantelpiece of his sitting-room he kept an interesting relic of

the famous battle in the shape of a cannon ball. On every

recurrence of " the glorious first of June " he had the ball

gaily decorated with ribbons, and, dressing himself in his full

naval uniform, paraded the town. Thus arrayed he would call at

various inns to drink to the memory of his old admiral and

success to the British Navy. In 1829—some years before his

death—the date of which is not now ascertainable—he appears to

have purchased his burial-place, erected his headstone, and left

instructions for the fixing of his much-prized curio upon it

after his death. The following year—November, 1830—he was

appointed to the rank and title of a commander in His Majesty's

Fleet (retired). He was then seventy-four, and from all accounts

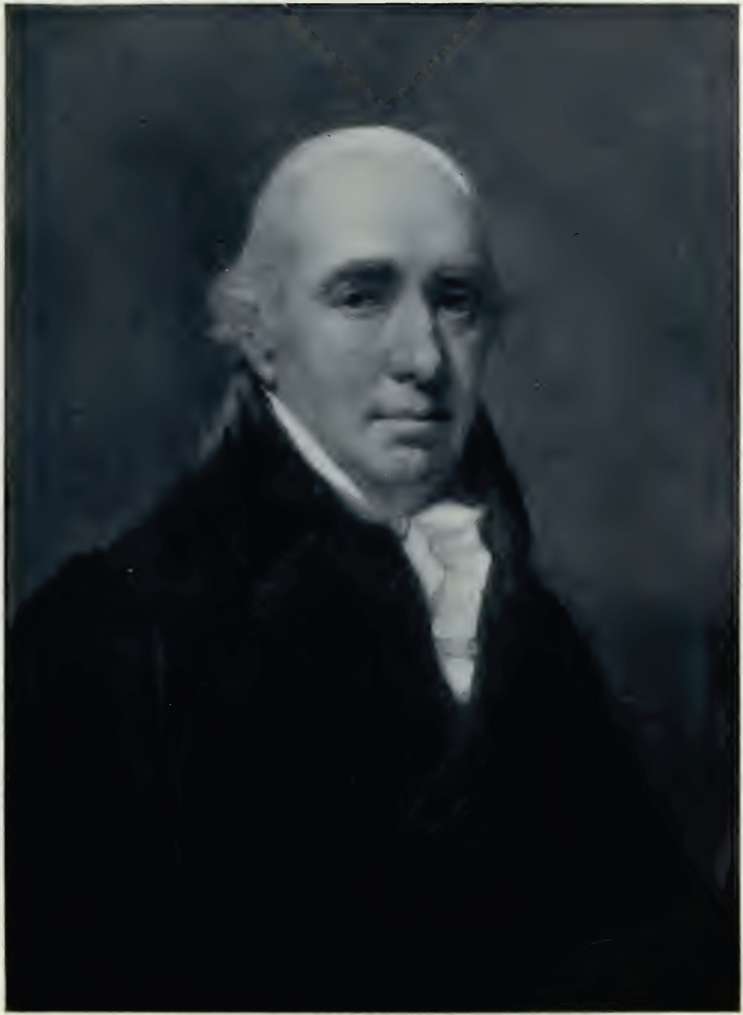

lived for some years afterwards.

Mr. William Thomson, of Upper Kinneil, was one of

the captain's intimate friends. To Mr. Thomson he left the

portrait (a photograph of which we reproduce) and his sword and

pistols. Mr. William Miller received other relics from a

grand-nephew of Potter's many years ago. Among these are a

miniature of the captain painted on ivory, and his three

commissions, two of which bear the signature of Lord Palmer ston.

XI.

George Husband Baird, Eighteenth

Principal op Edinburgh University (b.

1761, d. 1840).

This distinguished divine was born in 1761 in a

now-demolished house attached to the holding of Bowes, in the.

hollow to the west of Inveravon farm-house, in the Parish of

Borrowstounness. His father, James Baird, while a considerable

proprietor in the county of Stirling, at that time rented this

farm from the Duke of Hamilton. Young Baird received the

rudiments of his education at the Parish School of

Borrowstounness. Upon his father removing to the property of

Manuel the boy was sent to the Grammar School at Linlithgow. It

has been said of him that as a schoolboy he was more plodding,

persevering, and well-mannered than brilliant. In his thirteenth

year he was entered as a student in Humanity at Edinburgh

University. There he speedily evoked favourable notice because

of his devotion to his classwork and the progress which he made.

In 1793 he succeeded Principal Robertson in the Principalship at

the early age of thirty-three. Baird had married the eldest

daughter of Lord Provost Elder, who had paramount influence in

the Council, and exercised it for the election of his youthful

and untried son-in-law. We believe it used to be jocularly said

that his chief claim to the Principalship was as " Husband" of

the Lord Provost's daughter. Nevertheless the appointment turned

out well, although he was at a distinct disadvantage in

succeeding a man of high literary fame like Principal Robertson.

Baird held the Principalship for the long period of forty-seven

years, saw the students increase from 1000 to 2000, new

University buildings erected, the professoriate augmented, and

great developments in other ways. He lived through many long

strifes and litigations, and died leaving the Senatus still at

war. He was one of the ministers of the High Church of

Edinburgh.

But Baird did most excellent work,10 and

made a lasting name for himself outside the University. Towards

the close of his life he threw his whole soul into a scheme for

the education of the poor in the Highlands and Islands of

Scotland. He submitted his proposals to the General Assembly in

May, 1824, advancing them with great ability and earnestness.

Next year the Assembly gave its sanction to the scheme, and it

was launched most auspiciously. So intense was his interest in

this work that in his sixty-seventh year, although in enfeebled

health, he traversed the entire Highlands of Argyll, the west of

Inverness, and Ross, and the Western Islands from Lewis to

Kintyre. The following year he visited the Northern Highlands

and the Orkneys and Shetlands. Through his influence Dr. Andrew

Bell, of Madras, bequeathed £5000 for education in the Highlands

of Scotland. In 1832 the thanks of the General Assembly were

conveyed to him by the illustrious Dr. Chalmers, then in the

zenith of his oratorical powers. He died at his family property

at Manuel, and is buried in Muiravonside Churchyard.

XII.

Henry Bell (b.

1767, d. 1830).

At the ruins of Torphichen Old Mill, on the banks

of the river Avon, about six miles from Bo'ness, there was

unveiled, on a blustery afternoon in November, 1911, a tablet

bearing the following inscription : —

Henry Bell, Pioneer of Steamship Navigation in

Europe.

Born in the Old Mill House near this spot, 1767 a.d.

Died at Helensburgh, 1830 a.d.

The tablet, which is of Aberdeen granite, is

placed in the centre of the old gable, the only remaining part

of the original structure. It bears a representation of the

"Comet," showing how the funnel of the ship was also used as a

mast.

This worthy son of Linlithgowshire had an

interesting connection with our seaport. For many years

shipbuilding-was extensively carried on at Bo'ness. A great many

of the vessels were built for Greenock merchants for the West

India trade. The business was owned by Messrs. Shaw & Hart, and

with them Henry Bell, when about nineteen years of age, found

employment. It is said that when here his attention was directed

for the first time towards the idea of the propulsion of ships

by steam. His connection with Bo'ness extended over a period of

two years, after which he settled in Glasgow. For a number of

years pressure of business kept him from pursuing his idea of

propelling ships by steam. At length he designed, engined, and

launched the "Comet" on the Clyde in 1812. The little vessel was

herself in Bo'ness in 1813, and the event was one indelibly

imprinted on the memories of that generation. She probably came

down from the canal at Grangemouth, and when first seen was

thought to be on fire.

Bell, it seems, had sent her round to the yard of

his old masters to be overhauled. When she resumed her sailings

several local gentlemen took advantage of the first trip by

steamboat from Bo'ness to Leith. Her speed was six miles an

hour, and the single fare 7s. 6d.

The Bell family have been well known in and

intimately identified with the Linlithgow district for many

centuries. Some of the older members were burgesses of the

burgh, and many of them were engaged in the millwright industry

in the district. They were also tenants of Torphichen Mill,

Carribber Mill, and Kinneil Mill. Another family of Bells were

owners of Avontown, and were connected at different times with

the ministerial and legal professions, one of them having been

town-clerk of Linlithgow.

XIII.

Robert Burns,

D.D. (b. 1789, d. 1869).

In his notes of Bo'ness Parish, Mr. M'Kenzie says,

"A considerable number of clergymen might be mentioned as

connected with this parish by birth or residence. One family has

produced four clergymen of the Church of Scotland, all of

distinguished excellence, though, perhaps, the editor of the

last edition of 'Wodrow's Church History' is best known to

fame." The family referred to was that of John Burns, surveyor

of Customs, Bo'ness. His four distinguished sons were the

ministers of Kilsyth, Monkton, and Tweedsmuir, and the subject

of this sketch.

Robert was

born at Bo'ness in 1789, educated at the University of

Edinburgh, licensed as a probationer of the Church of Scotland

in 1810, and ordained minister of the Low Church, Paisley, in

1811. He was a man of great energy and activity, a popular

preacher, a laborious worker in his parish and town, a strenuous

supporter of the evangelical party in the Church, and one of the

foremost opponents of lay patronage. In 1815, impressed with the

spiritual wants of his countrymen in the Colonies, he helped to

form a Colonial Society for supplying them with ministers, and

of this society he continued the mainspring for fifteen years.

Joining the Free Church in 1843, he was sent by the General

Assembly in 1844 to the United States to cultivate fraternal

relations with the Churches there. In 1845 he accepted an

invitation to be minister of Knox's Church, Toronto, in which

charge he remained till 1856, when he was appointed Professor of

Church History and Apologetics in Knox's College. Burns took a

most lively interest in his work, moving about with great

activity over the whole colony, and becoming acquainted with

almost every congregation. Before the Disruption he edited a new

edition of Wodrow's " History of the Sufferings of the Church of

Scotland from the Restoration to the Revolution," in four

volumes, contributing a life of the author; and for three

years—1838-1840—he edited and contributed many papers to the

"Edinburgh Christian Instructor." He also wrote a life of

Stevenson Macgill, D.D., 1842. There is a memoir of Dr. Burns by

his son, Robert F. Burns, D.D., of Halifax, Nova Scotia; see

also "Disruption Worthies," and notice by his nephew, J. C.

Burns, D.D., Kirkliston.

XIV.

John Anderson (b. 1794, d. 1870).

John Anderson was known in his day and generation

as "the King of Bo'ness," and his name has been perpetuated in

the Anderson Trust, the Anderson Academy, and the Anderson

Buildings. He was the only son of John Anderson, teacher,

Bo'ness, and of Jean Paterson, his spouse, and was born and

lived all his days in the seaport. Possessing shrewd business

capacity, he in time became merchant, shipowner, and, later in

life, agent for the Royal Bank of Scotland. He conducted his

businesses with ability and success, and rose to considerable

influence in the place. In addition, he was connected officially

for many years with the local friendly societies, and devised

many schemes for their improvement. Mr. Anderson was a man of

strong will and tenacity of purpose, and left his mark 'on every

project with which he was associated.

Always fully alive to business possibilities, he,

to meet the increase in the population which followed the

establishment of Kinneil Furnaces, converted his extensive

cellarages in Potter's Close (now demolished) into

dwelling-houses. The consequent growth of the town at this time,

coupled with a renewal of the Greenland whale-fishing, led to a

great period of prosperity, in which he, as its principal

merchant, almost enjoyed a monopoly. He owned the whalers

"Success," "Alfred," and "Jean," and had a large share in the

boiling-house at the top of the Wynd. On the formation of

Bo'ness Gas Company, in 1842, he was appointed its first

chairman. To use a common phrase, Mr. Anderson was very lucky.

He did not, however, concentrate all his powers upon self-aggrandisement.

In him the poor of the town had a good friend during his

lifetime, and by his will he provided pensions to deserving

persons. Interested all his life in education, he advanced its

cause by •erecting and endowing the Academy which bears his

name. The foundation-stone of this building was made the

occasion of a great Masonic demonstration on the 12th of June,

1869. Another function in which, a decade before, he played a

prominent part was the visit of the eleventh Duke of Hamilton

and his wife, Princess Marie of Baden. They were received in

great style by Mr. Anderson, and entertained to cake and wine on

board the Greenland ship. Their Graces afterwards proceeded to

the Town House, and there gave a handsome donation towards the

erection of the Clock Tower.

Mr. Anderson died on 14th April, 1870, and was

buried beside his father, mother, and sister Margaret in the

lower churchyard at the Wynd. This burial-place is covered by a

large, flat stone bearing some appreciative words concerning his

mother and sister. The former is described as " active,

cheerful, and constantly occupied," and as having " sought

pleasure nowhere and found happiness and content everywhere." Of

the latter he says, " Active in her habit, kindly in her

disposition, she was a sister highly to be prized."

Some years ago Mr. Anderson's trustees, who had

been instructed to renew and keep the family tombstones in

order, resolved to erect a new monument to his memory in the

cemetery, as the lower churchyard was now practically abandoned.

So, upon Saturday, 24th December, 1904, Mr. William Thomson of

Seamore, one of the original trustees, performed the ceremony of

unveiling a handsome granite block, suitably inscribed, which

stands near the main entrance to the new cemetery.

XV.

Below we reproduce a somewhat humorous, but, we

believe, •quite accurate genealogy and character sketch of Mr.

Anderson, which is prefixed to a presentation volume of the

poetical works of Robert Burns (London, 1828), in the possession

of Masonic Lodge Douglas. It refers to Mr. Anderson's initiation

into Lodge No. 17, Ancient Brazen, Linlithgow, which apparently

met at Bo'ness for the purpose. The volume was presented by

Mr. Anderson, and, either out of compliment to

him or at his own desire (but, in either event, with his

knowledge and consent), the chronicle we refer to was prefixed.

Here is what the scribe has written—

"1. And in the days of the Kings called George

and William and of Queen Victoria, mighty Sovereigns of

Scotland, there dwelt in the ancient town of Bo'ness a virtuous

man called John, of the tribe of Anderson.

"2. Now, the genealogy of this John of Bo'ness is

as follows: —There was a pious man called John the Preacher, of

the tribe of Anderson, who took unto himself Agnes, the daughter

of Bryson. [This is evidently his grandfather, who was a Burgher

minister at Elsrickle, near Biggar.]

"3. And she bore him a son, John, who waxed

strong in knowledge, and in process of time taught the people

many things out of the law and the prophets. [This was his

father.]

"4. And John, the teacher, took unto himself an

excellent wife, called Jane, of the tribe of Paterson, whose

ancient progenitors were mighty rulers in Italy in the latter

days of the Caesars and the Apostles, and hence is derived their

Roman name of ' Pater' and ' filius '—father-son, now Paterson.

"5. And this daughter of the tribe of Pater bore

unto the teacher, John of Bo'ness, and also Agnes, who married

Robert, of the tribe of White, who is a dealer in things that

are hard in the royal city of London, and Margaret, a fair

maiden of good understanding, and much esteemed and respected by

all who knew her.

"And John of Bo'ness is a man that deals in all

kinds of merchandise. He ' takes heed to his ways,' as reminded

by the wise men of old and the prophets, therefore he has gold

and silver and menservants and maidservants, and also divers

ships that go far off for riches, even unto the borders of the

Holy Land. Moreover, this merchant was much respected for his

wisdom and for his upright ways. Wherefore he was made a ruler

among the people,13who

bowed down their heads before him when he sat in the judgment

seat; and his good name went abroad, so that there was none like

unto him in Bo'ness for skill in shipping."

The chronicle then concludes by recording Mr.

Anderson's initiation on the 14th of September, 1849.

XVI.

Admiral Sir George Johnstone Hope, K.C.B. (b. 1767, d.

1818).

We have elsewhere dealt with the Hope family in

connection with their ownership of Carriden estate. The notable

careers of the two admirals, however, claim some mention.

Sir George was the eldest son by the third

marriage of the Hon. Charles Hope Yere, and fifth child of his

father, who was the second son of the first Earl of Hopetoun. He

entered the Navy at the age of fifteen, and after passing

through the usual gradations attained the rank of captain in

1793, and that of rear-admiral in 1811.14 During

the interval he had commanded successively the "Romulus,"

"Alcmene," and "Leda" frigates, and the "Majestic," "Theseus,"

and "Defence," seventy-fours. At the battle of Trafalgar he was

present in the latter vessel. He served as captain of the Baltic

fleet from 1808 to 1811. In 1812 he went to the Admiralty, and

the following year held the chief command in the Baltic. In the

end of the same year he returned to the Admiralty, where he

remained as confidential adviser to the First Lord till his

death on 2nd May, 1818.

He was a very distinguished officer, and highly

appreciated in the service for his exemplary discipline, his

decision, promptitude, and bravery, and his veneration for

religion.

Admiral Sir James Hope,

K.C.B. (b. 1808, d. 1881).

James Hope was a child of ten when his father,

Admiral Sir George, died. His youth therefore was spent under

the direction of his mother and of his father's trustees.

Anxious to follow in his father's footsteps, he entered the

Navy, and had an equally distinguished career. He has been

described by one who served under him abroad as a brave

gentleman and a good-hearted soul, and this is borne out by all

who knew him in this neighbourhood. When in command of the "

Firebrand " he opened the passage of the Parana, in the River

Plate by cutting the chain at Obligado in 1845. He was

Commander-in-Chief in China, and brought < about the capture of

Peking. On two occasions he was seriously wounded. The first was

during the attack on the Peiho forts in 1859. He was directing

operations from the bridge of the " Plover " when a shell struck

the funnel chainstay. A fragment glanced off, and, striking

Hope, became deeply embedded in the muscles of his thigh. This

entirely disabled him for four months. His recovery was very

slow, and he was lame ever afterwards. The ship's surgeon was

able, after some trouble, to extract the splinter; and a

photograph of it is preserved, with a note giving full

particulars of the occurrence. The second occasion was near

Taeping. Hope, because of his disabled condition, was directing

movements from a sedan chair, and was in consultation with the

French Admiral. A shell from the guns of the enemy struck the

latter under the chin and decapitated him. Hope himself was

violently thrown from his seat, and his old wound reopened. He

was gallantly rescued by the late Tom Grant, of Bo'ness, who was

all through this campaign with the Admiral. In later years his

old chief succeeded in getting Grant a pension, although he had

scarcely completed his twenty-one years' service.

The late Tom Thomson, of Carriden, another old

naval man,

Admiral Sir James Hope.

(From a photograph in possession of Mrs. James

Kidd, Carriden.)

was with Hope while on the "Majestic " when she

was with the fleet in the Baltic under Sir Charles Napier. Hope

was an out-and-out Scot, and in his younger days agitated for

the introduction into the Navy of a Scotch uniform, especially

the Balmoral bonnet. The experiment was tried, but given up as

unsuitable.

He took great interest in his men on or off duty,

and arranged many private theatricals on the main deck for their

amusement, taking a special delight in the presentation of " Rob

Roy" and other Scottish pieces. Thomson spoke highly of his

discipline and the thoroughness with which he instructed and

drilled his men.

After the Pekin Treaty, in 1862, Admiral Hope was

engaged as an adviser at the Admiralty. He afterwards resigned

his command, and went into retirement. For some time he lived in

London, and afterwards settled at Carriden. In conjunction with

Lady Hope he associated himself in his later years with many

religious and philanthropic movements in the district. He bought

up some of the old properties in the Muirhouses, and remodelled

and rebuilt the village, including the old school and

schoolhouse. He was twice married, but had no family. The

Admiral died in Carriden House, and was buried in the northwest

corner of the churchyard at Cuffabouts. A cable from one of his

old ships surrounds the grave. His tombstone bears the

inscription, " Sir James Hope, G.C.B., Grand Commander of the

Bath, Admiral of the Fleet. Born 8th March 1808; died 8th June,

1881."

The late Sir John Lees, private secretary to the

Marquis of Townshend when Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and who

afterwards filled the office of Secretary to the Post Office in

Dublin, was in his youth brought up, Mr. Fleming says, in

Carriden parish. He was eminently successful in life, and

afforded a memorable example of the distinguished place in

society to which the careful cultivation and judicious

application of superior talents may raise their possessor. He

was created a baronet on the 21st June, 1804.

XVII.

James Brunton Stephens (b. 1835, d. 1902)

To Bo'ness belongs the honour of being the

birthplace of James Brunton Stephens, the poet of the Australian

Commonwealth. His father was John Stephens, who filled the

office of parochial schoolmaster of Borrowstounness from 1808 to 1845 with

much dignity and ability. The school and schoolhouse were then

situated in what is now known as George Place. James was born in

August, 1835. His

early education was received from his father, and among his

schoolmates were John Marshall and John Blair, who became

well-known doctors, the first in Crieff, and the latter in

Melbourne, Australia. On completing his school education he

proceeded to Edinburgh University. In all his classes he secured

an honourable place, but abandoned his course without taking a

degree. He was tempted away from the mere diploma by an offer to

become a travelling tutor, and with the son of a wealthy

gentleman he travelled for three years to Paris, Italy, Egypt,

Turkey, Asia Minor, Palestine, and Sicily. On returning to

Scotland he became an assistant master in Greenock Academy. In 1866, his

health having given way, he was advised to emigrate to

Australia. Arriving in Queensland, he obtained a tutorship in an

up-country station, and spent several years in learning the

sports and occupations of the bush. During this time he wrote

"Convict Once," his best poem, and later " The Godolphin

Arabian," a humorous and racy account of the sire of modern

thoroughbreds. In 1874 Mr.

Stephens received an appointment as a teacher under the

Department of Public Instruction in Brisbane. Here he began to

contribute to the local Press, and in 1876 won

a prize of £100 offered

by the Queenslander for

the best novelette. At this period he married and settled in one

of the Brisbane suburbs. In 1880 he

published a volume of miscellaneous poems containing many

humorous pieces that strongly appealed to the public. Mr.

Stephens latterly filled the position of Chief Clerk in the

Colonial Secretary's Office at Brisbane, and was

greatly esteemed for his geniality and wit. He was very

Australian in the selection of his themes, his inspiration being

found in his immediate surroundings. Among the humorous poets of

Australia he held a first place, but, like Hood, he could be

serious on occasion. In this vein he was equally successful. He

was keenly alive to the importance of uniting all the Australian

States, and in 1877 his poem, "The Dominion of Australia," did a

great deal to stimulate flagging interest in federation. On the

1st of January, 1901, he published a poem in the Argus entitled

"Fulfilment," which was dedicated, by special permission, to Her

Majesty Queen Victoria.

In June of the following year Mr. Stephens died

in his sixty-seventh year, and was survived by his widow, a son,

and four daughters.