|

1. Local Evidences of Early Mining: Privileges of

Miners under 1592 Act r "In-gaun-ee" System: Access Shafts,

Ladders, and Spiral Stairs— 2. Lawless Behaviour of Miners leads

to Act of 1606 : Colliers and Salters Enslaved as "Necessary

Servants": Sold with Colliery: Partial Emancipation in 1775:

Serf System Completely Ended in 1779—3. Agitation for Abolition

of Woman and Child Labour in Mines: Royal Comission Appointed to

Enquire : The Act of 1842— 4. Interesting Local Evidence—5. The

Coal and Other Strata in Carriden Parish—6. Bo' ness

Coalfield—7. Preston Island and its-Coal Mines and Saltpans—8.

The Local Coal and Ironstone Mines of Sixty Years Ago—9. Some

Mining Calamities: Colliers' Strike :: Newtown Families—10. Two

Alarming Subsidences.

I.

The Bo'ness

coalfield at one time contained a very large supply of coal, and

has been worked more or less extensively since the thirteenth

century. Early in that century a tithe of the colliery of

Carriden was granted to the monks of Holyrood, and until a few

years ago evidences of the workings in those early times were to

be found in the old Manse Wood on Carriden shore. At that time

the old roads were opened up and modernised in an unsuccessful

exploit for coal under the glebe.

In the fifteenth century the Scots Parliament,

believing that Scotland was full of precious metals, and hoping

to derive a large revenue therefrom, enacted that all mines of

such should: belong to the King—James I. As the landowners had

thus no encouragement to develop their mineral resources, the

Act was. practically a dead letter, and in 1592—in the reign of

James IV.—the Parliament was compelled to modify the old statute

to the effect that the Crown was only to get a tenth part as; a

royalty. This same statute made mention of the hazardous, v

nature of the miners' occupation on account of the evil air of

the mines and the danger of the falling of the roofs and other

miseries. It therefore exempted the miners from all taxation and

other charges both in peace and war. Their families' goods and

gear were likewise specially protected. Some have thought that

Parliament, even at this early date, was taking a commendably

humane interest in the safety and comfort of the miners. Others,

again, have asserted that the privileges conferred were meant to

act as an inducement to foreigners to settle in this country for

the purpose of searching for and working the minerals.

In the early days of mining the fortunate

proprietors of land and coal seams under it carried on their own

coal works for the most part. Those were still the days of

feudalism (though not of slavery, which had died out in the

fourteenth century), and vassals and retainers on the estates,

quite naturally, turned their hands to the new industry of coal

winning. Their wages were paid partly in money, but mainly in

produce.

Outcrops were frequently discovered at brae

faces, and the coal was originally wrought downwards and inwards

from the surface on what was known as the " in-gaun-eesystem.

Women, girls, and boys all assisted as bearers by carrying out

the coal to the bings, where they stored it until sold.

As time went on the importance of the industry

came to be keenly realised by the proprietors of the coal seams.

The idea appears to have occurred to them that the shafts, which

hitherto had only been sunk for the purpose of ventilation,

might be widened, deepened, and used for getting access to the

coal lying at greater depths, and also for bringing it to the

surface. Thereupon the shafts were rigged out with short wooden

ladders resting on crossbeams when the shaft was too deep for

one long sloping ladder. Those descending the shaft went down

the first short ladder of six or eight rungs, passed along the

beam a foot or two, then on to the other ladder, and so on till

they completed their dangerous descent. This system was so

difficult and dangerous that the ladders soon came to be

replaced by spiral stairs. An old spiral stair shaft was to be

seen at the foot of the Back Hill, Corbiehall, about thirty

years ago. Though the stairs were safer than the ladders, the

toil of the bearers was in no way lessened. Later still the

masters introduced the windlass, and subsequently the one-horse

gin. The bearers were thus relieved of a part of their

burdensome toil, but they still dragged the coal to the pit

bottom in primitive hutches without wheels.

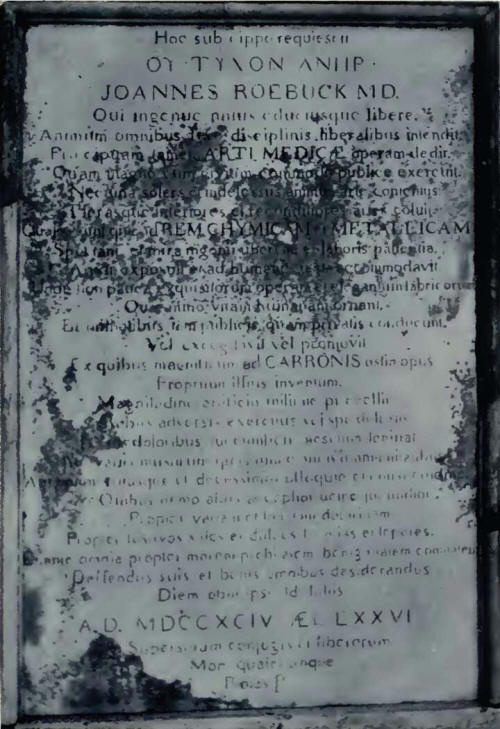

Dr. Roebuck's Tombstone in Carriden Churchyard.

II.

"Whether it was owing to the privileges given

them by the Act of 1592 or to the evil effect which their

underground occupation had upon their minds we know not, but, at

all events, the colliers as a class suddenly became lawless and

greatly given to wilfully setting fire to the collieries from

motives of private revenge. Accordingly, Parliament enacted that

all who were guilty of " the wicked crime of wilfully setting

fire to coal-heuchs" should suffer the punishment of treason in

their bodies, lands, and goods. This was followed up by an Act

in 1606, under which the privileges and exemptions of the

colliers were recalled and their freedom very materially

curtailed. The colliers, by their foolish behaviour, brought

this upon themselves, but pressure was brought to bear on the

Legislature by the Earl of Winton, then a favourite at Court,

and the largest coalowner and salt manufacturer in Great

Britain. By the new Act colliers and salters were enslaved as "

necessary servants," and regarded as a pertinent of the lands

where they were serving. It is evident that the chief reason for

this extreme course was the fear which possessed coalowners,

that unless some such compulsory steps were taken there would in

future be great difficulty in getting men to undertake so

perilous a calling.

Another reason was the increased demand for coal,

especially for export. Inducements were held out to the colliers

at busy centres in the shape of bounty money. The men were thus

drawn to places where the demand was greatest, and many

districts were thereby depleted. So the Act decreed that they

were bound to remain, and to be practically enslaved at the

colliery where they were born. No strange collier could get

employment at any coal work without a testimonial from his last

employer; and, failing such testimonial, he could be claimed

within a year and a day by the master whom he had deserted.

Whoever discovered the deserter had to give him back within

twenty-four hours under a heavy penalty; and the deserter was

punished as a thief—of himself. The Act also gave colliery

owners power to apprehend all vagabonds and sturdy beggars and

put them to work in the mines. So long as a coal work was in

operation on any estate the colliers were not at liberty to

leave without the proprietor's consent. They were, in fact, says

Mr. Barrowman,2 attached

to the work, formed a valuable adjunct to it, and enhanced the

price in the event of a sale. He gives an illustration as late

as 1771 where the value of the ownership of forty good colliers,

with their wives and children, was estimated to be worth £4000,

or £100 each family. Parents bound their children in a formal

manner to the work by receiving gifts or arles from the master

when they were baptised. Not only were the colliers attached,

but by an Act in 1641 other workers engaged in and about coal

mines were prohibited from leaving without permission.

Appended to a lease in 1681 of the coal and salt

works at Bo'ness in favour of James Cornwall of Bonhard was a

list of colliers and bearers delivered to him in terms of the

tack. There were thirteen coal hewers, six male bearers (one of

whom was reckoned a half), and thirty-one female bearers (seven

of whom were reckoned a half each), in all, thirteen coal hewers

and thirty-three bearers. These, with one oncost man, the tenant

acknowledged to have received and undertook to deliver over at

the end of the lease, or an equivalent number.

Under this law of bondage the poor collier and

salter lived for nearly one hundred and seventy years, until, in

1775, an Act was passed emancipating all who after that date

should begin to work as colliers and salters. If working

colliers were twenty-one years of age at the time of the Act,

they were to be emancipated at the end of seven years. Those

between the ages of twenty-one and thirty were to serve ten

years longer before gaining freedom. It will thus be seen that

the conditions under which freedom was to be given were irksome,

and many of the workers accustomed to their conditions failed to

take advantage of the Act, and remained serfs until their death.

A complete stop, however, was put to the serf system in 1799. It

was then enacted that " all the colliers in that part of Great

Britain called Scotland who were bound colliers shall be and are

hereby declared to be free from their servitude." While the

colliers were serfs, they were not slaves, for they received

wages, and towards the end of the eighteenth century the

conditions of their employment were much improved. Moreover,

when coal mining, with the general advance of Scottish commerce,

became a more profitable industry, the masters had a difficulty

in getting enough men, and increased the wages to induce people

to work in the pits

and hard and degrading work it was. Before the

days of the underground tramway the coal was carried to the pit

bottom in creels fastened to their backs, hence the term bearer.

Women and girls were preferred to men and boys for such work,

as, curiously enough, they could always carry about double the

weight a man or boy could scramble out with. The creel was

superseded about 1830 by baskets on wheels, and latterly by

wooden boxes, which were pushed along the underground railways.

The term "bearer" then ceased, and that of "pusher" or "putter"

was substituted.

A great many of the annual fairs or ridings of

the miners— and doubtless those of the Newtown, Corbiehall, and

Grangepans miners—really originated as a day of rejoicing on the

anniversary of their freedom.

The subject of female labour in mines had, as

early as 1793, aroused some attention, but not till 1808 was the

matter brought prominently before the public. Mr. Robert Bald,

Edinburgh, who took a leading part in the agitation, instanced

the case of a married woman in an extensive colliery which he

had visited. She came forward to him groaning under an excessive

weight of coals, trembling in every limb, and almost unable to

keep her knees from sinking under her, and saying, " Oh, sir,

this is sair, sair, sair wark. I wish to God that the first

woman who tried to bear coals had broken her back, and none

would have tried it again."3

The public indignation was at length aroused.

Mainly through the philanthropic and deeply sympathetic efforts

of Lord Ashley (afterwards seventh Earl of Shaftesbury) a Royal

Commission was appointed to inquire into the condition of the

mining population, and particularly the question of women and

child labour in mines. Mr. Barrowman

says the report of that Commission in 1812 drew instant and wide

attention to the grave evils connected with the employment of

women and young persons underground, and a statute was passed in

that year prohibiting the employment of females of any age and

beys under ten years of age in any mine or colliery. The Act was

not regarded by the persons interested with unqualified

satisfaction. It threw many females out of an occupation to

which they had been accustomed, and they would doubtless take

some time to fit themselves into the new state of things. A

curious sequel occurred in the Dryden Colliery, Midlothian,

where about a score of girls assumed male attire and wrought in

this disguise for three months after the Act was passed. They

were at length summoned to Court in Edinburgh. On promising not

to go below again they were dismissed.4 In

one extensive colliery in the east, at least, the workers

petitioned against the bill. Out of the signatures of 122 men

and 37 women and girls there were 45 of men and 25 of females

marked with a cross (70 out of 159 being unable to write their

names), showing in the clearest manner the need there was for a

better system of home and school education, and justifying in

the most emphatic way the passing of the Act. The successive

Acts of Parliament passed since 1842 have tended towards the

improvement of the miner and of the conditions in which his work

is carried on; and perhaps there is no employment in the country

in which the workman is now better safeguarded by legislation.

IV.

A vivid idea of the terrible state of matters

which Lord Ashley's Commission was the means of ending is

obtained from the evidence taken by the special Commissioners at

the various collieries throughout Britain. The Commissioner for

Scotland was Mr. R. H. Franks, whose Report contains between

four and five hundred examinations.5 We

append the whole of the precognitions taken here about 1840.

They make interesting, though somewhat depressing, reading—

James John Cadell.—There

are at present emplpyed below ground in our pits about 200 men,

women, and children; fully one-third are females. No regulation

exists here for the prevention of children working below.

I think the parents are the best judges when to

take their children below for assistance, and that it is of

consequence for colliers to be trained in early youth to their

work. Parents take their children down from eight to ten years

of age, males and females.

The colliers are perfectly unbound at this

colliery; they have large families, and extremely healthy ones.

I believe most of the children can read. There are two schools,

at which children can be taught common reading for 2d. per week.

There exist no compulsory regulations to enforce colliers paying

for their children or sending them to school. Every precaution

is taken to avoid accidents; several have occurred, and

occasionally happen from parts of the roof and coal coming down

on the men; one lad was killed a short time since. The work is

carried on about twelve hours per day, and the people come and

go as they please.

Archibald Ferguson>, eleven years old, putter.—Worked

below for four years; pushes father's coal with sister, who is

seventeen years of age from wall face to horse road. Pit is very

dry and roofs lofty. Sometimes work twelve, and even sixteen

hours, as we have to wait our turn for the horse and engine to

draw. Never got hurt below. Get oatcake and water, and potatoes

and herrings when home. The river which passes through Bo'ness

is called the water. Fishes live in the water; has often seen

them carted from boats; never caught any. I walk about on the

shore and pick up stones or gang in the parks (fields) after the

birds.

Janet Barrowman, seventeen years old, putter.—I

putt the small coal on Master's (Mr. Cadell's) account. Am paid

2£ each course, and run six courses a day; the carts I run

contain 5 J to 7 J cwts. of coal. Father and mother are dead.

Have three brothers and five sisters below; two elder brothers,

two sisters, and myself live at Grangepans. We have one room in

which we all live and sleep. There has been much sickness of

late years about the Grange; few have escaped the fever. A short

time ago before the death of my parents we were all down, father

and all, with low fever for a long time. Mother •only escaped

who nursed us. Fever is always in the place. {Reads very

indifferently.)

The village of Grangepans has been much visited

with •scarlet fever and scarlatina; the place is nearly level

with the Forth, and the houses are very old, ill-ventilated, and

the foul water and filth lying about is sufficient to create a

pestilence.

Note.—The

last paragraph is apparently a comment of the Commissioner's

own.

Mary Snedden, fifteen years of age, putter.—I

have wrought at Bo'ness pit three months. Should not have

"ganged," but brother Robert was killed on the 21st of January

last. A piece of the roof fell upon his head, and he died

instantly. He was brought home, coffined, and buried in Bo'ness

Kirkyard. No one came to inquire about how he was killed; they

never do in this place.

Charles Robertson, overseer of the Bo'ness Coal

Works.— Since

the building of the Newtown the colliers have been more settled

as to their place of work, but they still continue to take down

very young children, which impedes instruction. Most children

can be instructed if the parents please—and fairly so. There are

two schools. The one in the Newtown has a well-trained teacher

from Bathgate Academy, and one is shortly expected at Grangepans.

Men would do well to let their children remain up

till thirteen years old, as they would be more use to them

thereafter. No married women now go below; the elder females who

are down are single or widows. There are many illegitimate

children in the pits that do not get any education.

A man with two strong lads can get his 6s. 6d. a

day, fair average wages, as there is no limitation to work.

Rev. Kenneth M'Kenzie, minister of

Borrowstounness.— When

children once go to work in the collieries they continue at it;

and they go as early as eight years of age; but the age is quite

uncertain, depending entirely on the convenience, cupidity, or

caprice of the parents.

The tendency to remove children too early from

school operates to the injury of many in after life. It proves

an obstacle to future advancement, and renders the mind much

more liable to the influence of prejudice.

With regard to the children employed at the

colliery education is at present in a very unsatisfactory state,

and will continue so if the matter be allowed to rest with the

colliers. A good plan is adopted at some collieries. Every man

employed is obliged to pay a small weekly sum for education. A

sufficient sum is thus easily raised, and a properly qualified

teacher is appointed by the proprietor or master. Individuals

are thus constrained to send their children to school who

otherwise might be apt to neglect their education. The day and

evening school in Bo'ness, Newtown, is specially for the

colliery population, but it is not attended; at present the

teacher only receives 7s. a week in voluntary fees. The teacher

has not been trained. He teaches reading, writing, and

arithmetic as well as most adventurers do.

The parochial school is one of the best in

Linlithgowshire, but the colliers seldom send their children to

it.

V .

Mr. Ellis, writing

of Carriden in the eighteenth century, stated that the parish

was full of coal, which was of fine quality, and the only fuel

then used. It was carried to London, to the northmost parts of

Scotland, and to Holland, Germany, and the Baltic. As to price

it sold at a higher figure on the hill and to the country people

who lived near than any coal in Scotland. Nearly half a century

later Mr. Fleming7 wrote

that about 400 yards west of the village of Blackness a bed of

calcareous ironstone cropped out on the beach, dipping into the

sea in the same direction. When carefully prepared this formed a

hydraulic cement of a very superior quality, and in the

beginning of the nineteenth century had been actually wrought

for that purpose. This stratum was covered with a strong shale,

otherwise called blea, varying in thickness from one to twenty

feet interspersed with halls of clay ironstone. The alum shale

was at one time used in the manufacture of soda, but the work

had been discontinued and the premises dismantled.

There were many seams of coal in the parish, some

of which had been wrought at their crops or outbursts centuries

ago. The coalfield in its western division was supposed to

extend' across the Forth, and to be connected with the coal

formation in the opposite district in the county of Fife. The

strata were known to the depth of one hundred and thirty-five

fathoms, having been passed by the miners in sinking pits and

other operations in the coal mines. The deepest seam then known

was the Carsey coal, rising to the north-east along

the-seashore. This seam and the Smithy seam came out to the

surface a short distance to the east of Burnfoot. The Foul coal

and Red coal took on to the west of the road leading to

Linlithgow. The western Main coal was only in the south-west-of

the parish, as there was not sufficient cover for this seam to

the east and north. This coalfield passed through the south-west

boundary of the parish into the Parishes of* Borrowstounness and

Linlithgow. In approaching the north the dip gradually came

round more west; in the middle of the field it was generally

north-west. To the east of Burnfoot, after passing the crop of

the Carsey coal, no coal was to be found. It was a curious fact

that in a district where so many seams of coal occurred

whinstone should be found so abundantly. The Irongath Hills

consisted of hard whinstone resting in the coal strata; nor did

it present itself only in crops on the top of eminences; but it

was found in regular seams between, and even-in actual contact

with the coal. In these hills there was a bed of coal varying

from one to eight or ten feet in thickness which had. whinstone

both for its roof and pavement; and between the Western main

coal and the Red coal the seam of whinstone was about seventy

feet thick. The fossil remains that have been* found in the coal

formation consisted of reeds of different kinds. Shells and

impressions of leaves were also of more or less-frequent

occurrence, and on one occasion workmen fell in with a beautiful

specimen of that curious extinct genus of fossil plants, the lepidodendron. The

surface deposits in the west part of the parish near the shore

consisted of sea sand and .shells resting on blue clay and mud,

the clay resting on the coal formation; and in the south-west

there was found yellow brick •clay, with sand and gravel.

Ice-transported boulders that had been met with were often of

trap, their weight varying from 3 or 4 cwts. to 4 or 5 tons.

VI

With regard to the coal in the adjoining Parish

of Bo'ness, Dr. Rennie8 has

told us that it was wrought here more than three hundred years

ago. The depth of the pits in 1796 was about forty-two fathoms.

The seam of coal was from ten to twelve feet in thickness, and

was nearly exhausted. This was know as the Wester Main Coal

Seam. There were various seams— some of them of a superior and

others of a very inferior quality. All of them had been wrought

in different places and at different times to a great extent,

particularly in and about Bo'ness. It 'was proposed to sink a

pit to the west of the town. The depth to the principal seam in

this quarter might be about seventy fathoms; but there were

several seams at a much less depth. Coal was at that time all

worked on the pillar or stoop and room -system. The average

quantity raised in twelve months for some time before he wrote

might be about 44,000 tons. A •considerable part of the great

coal had been exported at 7s. 9d. per ton. The remainder was

disposed of in the coasting trade .and in the adjacent country.

A great many of the chew coals were carried by contract shipping

to the London market .at 6s. per ton. What was known as the

small coal or panwood was consumed by the salt works, which

consisted of sixteen pans, .-and employed about thirty salters

and labourers. The annual quantity of salt made was about 37,000

bushels, which was partly disposed of in the coasting trade.

Most of it, however, was for the supply of the country to the

south and west of Borrowstounness. The number of colliers,

coal-bearers, labourers, and carters employed about the colliery

was probably 250.

In 1843 Mr. M'Kenzie9 wrote

that the beds in Bo'ness Parish were all of the coal formation.

No coal had in his time been found in this district under the

Carsey coal. Even yet it appears to be the lowest of the

workable seams. Above the strata in the Snab section, which he

referred to in detail, were one or two inferior coal seams which

had been partially wrought in former times for the salt pans.

And at Craigenbuck, further to the westward, a seam of limestone

was also at one time wrought, and afforded an excellent building

mortar. The seams of coal about Bo'ness were, generally

speaking, of good thickness and excellent quality. The

neighbourhood of the Snab (known now as Kinneil Colliery) had

been proposed as the most favourable situation for a new winning

of the coalfield; and the establishment of a colliery there was

expected to be a great advantage to the town.

We have thus endeavoured to indicate in a general

way the nature of the geological strata. For those who may

desire more detailed data, however, we print in Appendix an

illustrative and reliable section of the local coalfield.

VII.

Situated in the Firth to the north of Bo'ness

roads is Preston Island, so-called after the Prestons of

Valleyfield, to whom it belonged. Looking from Bo'ness it

appears to contain a considerable mansion-house, but a closer

inspection dispels this impression, and reveals the ruins of

t}ie buildings after referred to. A visit to Preston Island,

says Mr. Beveridge9 in

one of his interesting volumes, is a very pleasant outing. But

let strangers be cautious in straying over it to avoid falling

into the open and unguarded coal pit, which is generally full of

water. Till the end of the eighteenth century the island was

merely an expanse of green turf at the eastern extremity •of the

reef known as the Craigmore Rocks, which being within low-water

mark all belong to the estate of Low Valleyfield. On Sir Robert

Preston succeeding to the property at the beginning of the

nineteenth century he conceived the idea of converting this

lonely spot into a great centre of trade. The seams of coal

which underlie the basin of the Forth were here cropping out -at

the surface. It therefore seemed quite feasible to undertake the

revival of the coal and salt industries which in former days,

under the auspices of Sir George Bruce, had made the fortune -of

Culross and its neighbourhood. Sir Robert had attained to great

wealth, partly obtained in trade as the captain of an East

Indiaman, partly accumulated by speculation, and partly by

marriage with the daughter of a wealthy London citizen. He

accordingly erected a large range of buildings on the island,

"including engine-houses, saltpans, and habitations for colliers

and salters. Pits were sunk, fresh water brought from the

-mainland, and, for a period, a vast industry was carried on.

The Forth resounded with the working of the engines, and the

loading of vessels with coal went on almost constantly. But,

'for various reasons, the affair was a losing concern.

Ultimately it completely collapsed, leaving the baronet out of

pocket to the extent of at least £30,000. Fortunately his means

were such that after so great a loss he still remained a man of

immense wealth.

After the colliery was stopped the saltpans were

let and worked for a considerable period, the last tenant of

them .adding to his legitimate occupation that of an unlicensed

distiller of whisky. Having received a hint, however, that the

Revenue officers were upon his track he decamped. Preston Island

has since then remained a deserted but singularly ^picturesque

object.

VIII.

The surface of the parish- sixty

years ago, owing to the coal and ironstone mining, must have

presented a busy .aspect. Evidences of this are yet to be

gathered from the numerous bings of blaes and other refuse still

standing in various districts. If we study the matter, moreover,

from the old Ordnance maps we find that the place was at one

time riddled with shafts and air passages. These shafts, both on

the shore in Grangepans and Bo'ness and on the hills above, have

been carefully filled up, and the surface as a whole is

comparatively secure. All the refuse bings on Grange estate have

of late years been removed by the Laird of Grange. Kinneil

Colliery Company also are gradually diminishing their old bings.

As we have said in another chapter, Nos. 1, 2, 3,

and 4 shore pits, opened by Messrs. John & William Cadell, and

also their No. 5 pit, were all abandoned early last century, and

remained flooded till 1859.

More than half a century ago, while the shore

pits remained drowned, the Grange mining was practically done on

the hill—some of it on that estate, and some at the Burn and

Mingle pits, taken on lease from Kinneil colliery.

Four of the Grange pits were near the Drum. The

Level pit above Bridgeness; the Meldrum pit, at the head of the

old incline railway; the Kiln pit, south from it, on east side

of the road; and still farther south the Miller pit. The Meldrum

pit and the Kiln pit are both now untraceable, having been

lately filled up by the present laird, like all the other old

pits at Grange, except the Doocot pit at Bridgeness and the

Miller pit. Another busy centre was the pit known as the Acre

pit, opposite Lochend, near the Muirhouses. Coal and ironstone

were both worked here, and a tramway ran down to the incline at

the Meldrum pit. Here was a double 3-feet railway leading down

to Grangepans, which was constructed by Mr. James John Cadell

about 1845. Although the tramway from Lochend along the south

side of the Muirhouse road and the incline railway were all in

full working order in comparatively recent times, all traces of

them are now effectually removed. The incline was finally

dismantled about 1890, when a commencement was made with

Philpingstone Road.

In the middle of last century there was quite a

congeries of pits in the vicinity of Northbank, which were

opened up when-Mr. Wilson of Dundyvan leased Kinneil colliery,

and began to search for ironstone. Nos. 5, 6, and 7 were all

situated near the Red Brae, on the north side of the Borrowstoun

and Bonhard road. There was a waggon railway here also. It ran

from Kinneil, by way of Newtown, up through the Mingle-and Burn

pits at Kinglass, and on to No. 7 at Northbank. The-empty

waggons were taken by small engine right up. Latterly the engine

was done away with, and horse haulage was adopted instead. There

was also a pit at the top of the Red Brae, known as Duncan's

Hole. In fact, the road itself was in-olden times called

Duncan's Brae.

What was known as the Borrowstoun coalfield

included the-Mingle and Burn pits, and also the Lothians pit at

the east: end of the old Row, Newtown.

But there were numerous other pits scattered over

the-surface of the district—Kinneil colliery, especially in Mr.

Wilson's time, having been very extensively worked. It would;

have at one time fully two dozen pits, and these were chiefly

known under a number. The Mingle was No. 1; the Burn, No. 2;

Nos. 3 and 4 were north of Bo'mains Farm; Nos. 5, 6, and 7, as

already stated, near the Red Brae; No. 8 was Duncan's Hole; No.

9 was the Cousie mine, south of Northbank and east of the Cousie;

No. 10 was where the new Burgh.' Hospital now is; Nos. 11 and 12

were at Bonhard—the former in the field east from the foot of

Red Brae and the latter to the east of the Cross roads; No. 13 Avas below

Borrowstoun Farm; No. 14 where the Newtown store now is; and No.

15-west of the present football field at Newtown; No. 16 was in>

the field east from Richmond House; No. 17, a small pit, to work

ironstone at the back of Old Row, Newtown; No. 18 was the

Lothians. An important pit at one time was-at the Chance, and

another south from the Gauze House was. called Jessfield. In

later times there was what was known as the New Pit on Grange

estate, east of the Gauze. Two old pits were the Bailies pit at

the head of the Cow Loan, Borrowstoun (sunk about 1830 by Mr. J.

J. Cadell, but abandoned because so much whin was found); and

the Temple pit, on the lands of Northbank east from the latter

pit. There was also the Beat pit, where the new cemetery now is,

and the Store pit, near the present store at Furnace Row. Nos. 1

and 2 Snab were in course of being sunk about the period we

refer to, the only pit in that neighbourhood being the Gin pit,

a little to the east. In the town there were two pits at the

foot of the Schoolyard Brae, but although coal was raised they

were latterly mainly used for pumping. The condensing engine

which James Watt invented and completed at Kinneil was first

fitted up at the Burn pit. It was afterwards transferred to the

Temple pit, and its large wheel, when in motion, gave the miners

much amusement. There are still a number of retired miners of

the old school resident about Bo'ness,10 and

it is very entertaining to listen to their intelligent

description both of the surface when it was studded with pits

and of the various underground workings themselves. In nearly

all cases ironstone was wrought, as well as coal, and was

calcined at the pithead.

IX.

The mining in all these years has naturally

affected both the surface and.the underground workings. The

surface has in some places been considerably lowered. In other

places, where the old stoop and room system was used, before the

introduction of the long wall method, the ground is to some

extent honeycombed, and holes fall in when the roof gives way

over seams not far below the surface. Considering the extent of

the mining operations here, the calamities which have befallen

the mining population have been comparatively few. The most

serious of these occurred at the Store pit at Kinneil and in the

Schoolyard pit. Four miners were engaged in driving a mine in

the Store pit when the water rushed in upon them from adjoining

waste workings, drowning all four. Charles Robertson, foreman,

already referred to in this chapter, lost his life along with

his son and a nephew in the Schoolyard pit. The three were

working at the bottom near the main coal. The day was a stormy

one, and the air down below had been diverted in some way, with

the result that all three were suffocated. A terrible boiler

explosion also occurred here. There were five or six boilers in

a row at the pithead. One of them had been under repair, but the

water not getting in freely, the boiler became overheated, and

burst. One portion landed in the garden at the rear of the

Clydesdale Hotel. Strangely enough, the men at the pithead

escaped. Bricks and stones from the boilei foundations were sent

broadcast with terrific force, and for long distances. A woman

and child were passing the old post office in South Street at

the time. The woman escaped, but the child, who was by her side,

was struck by a brick and killed on the spot.

During the time of Mr. Wilson there was a great

miners' strike in the county. Miners from the Redding district

in large numbers made a raid on the town bent on plundering

Kinneil store for provisions. This and the general excitement

caused Mr. Wilson to send to Edinburgh for a detachment of

soldiers. In response, a company of cavalry from the 7th

Dragoons arrived on the scene, and were billeted at Kinneil and

the Snab. Soldiers and miners fraternised freely, and had great

ongoings. The officer in charge was a keen sportsman and

challenged Mr. Wilson to run his carriage horses against those

of the troopers. Several races came off in the Brewlands Park,

the scene of many a former horse-racing contest. The soldiers

remained for several weeks, and had many an escapade. On one

occasion some of them commandeered the town drum and drummed

themselves round the streets.

The leading families in the Newtown about seventy

years ago were the Hamiltons, Robertsons, Grants, Nisbets,

Gibbs, and Sneddens. The Old Row constituted the Newtown of

those days, and about one hundred families resided there. It was

a strict preserve for the miners and their families, and no

lodgers or foreigners were admitted. Bynames were very

plentiful, and there were lords, dukes, and earls among them.

Peers and Commoners alike resided in the Old Row. Archibald

Hamilton and his family represented the lords; Sandy Hamilton,

the dukes; and Richard Hamilton, the earls. The Hamiltons of

Grangepans are all related to the earls and lords Hamiltons of

Newtown. The dukes belong to a separate branch, and are

connected with the Robertsons and Sneddens.

X.

Two alarming subsidences have occurred in Bo'ness

during the last half-century. They have been described by Mr.

Cadell12 as

follows: —

"One Sunday evening about thirty years ago, as a

local preacher was addressing a meeting on the subject of the

fall of the Tower of Siloam in the Old Town Hall below the Clock

Tower, and close to the harbour, the congregation were startled

by an uncomfortable feeling as if the floor of the building was

subsiding beneath them. No active calamity happened, although a

terrible danger was very near, and a kind Providence rewarded

the faith of the worshippers and permitted them quietly to leave

the building after the close of the service. Next day

investigations showed that a huge hole 60 feet deep had formed

just under the floor, owing to the giving way of the roof of the

Wester Main Waste. In a short time the tower began to sink, so

as to necessitate its demolition by- the authorities. A small

shaft was subsequently sunk to ascertain the nature of the

cavity, and many had an opportunity of going down and wandering

through the old workings about 50 feet below the surface. The

seam was about 10 feet thick, and the old miners had worked it

in large square pillars, with beautifully dressed faces and an

excellent roof. The surface, however, was so near that the thin

roof at places had fallen in, and one of the ' sits ' had taken

place right under the Town Hall. This hole was solidly packed

with stone when the Clock Tower was rebuilt.

"On another Sunday evening, 2nd February, 1890,

an alarming subsidence took place on the shore end of the old

harbour, about 200 feet north of the Clock Tower, and close to

the ' tongue ' that existed up till then between the east and

west piers. The ground gave way under the railway, and when the

sea rose the water gushed down like a roaring river,' enlarging

the aperture, and leaving the rails and sleepers suspended in

mid-air. The hole was plugged up with timber, straw, and

brushwood, and filled to the surface with ballast and clay. All

seemed safe, and heavy trains passed over the place until the

20th of February, when a second and larger subsidence took

place, into which the sea at high tide rushed in enormous

volumes. It looked as if all the dip workings of the Kinneil

Colliery were to be drowned, but so large was the reservoir in

the Old Wastes that the tide had not time to fill these up

before it was excluded. The hole was securely filled with a

foundation of slag blocks, covered with clay and ballast, and it

was estimated that 2000 tons of material were swallowed up

before the cavity was finally levelled over, in the beginning of

March. The seam in these sits had

a steep dip westward or north-westward, so that the material

slid far down as it was dropped in, and was spread over a much

larger area of the waste than if the working had been level.

Only a few feet of solid rock had been left between the coal and

the bottom of the mud in the harbour, and it is marvellous that

the old miners were not drowned out a century ago after their

temerity in working the seam so near the outcrop below the

foreshore. The water that gained entrance during the last

subsidence subsequently found its way down into the Kinneil

Company's workings to the west, and for a time entailed heavy

pumping there." |

|