|

1. Period of One Hundred Years : The Four Acts

Embraced in it—2. The Making of the Harbour Basin : "Slothfull"

Masons : £30 Expended on Street Repairs—3. Construction of the

Waggon Road and of New Street—4. Petitions from Inhabitants:

Providence Road: The Syver Well and Charles Addison's

Reclamation of Foreshore—6. Complaints about the Streets: The

Rouping of the Street Manure: The Letting of the Bye-ales:

Drummond's Imprisonment—6. Throwing Ballast into the Harbour : A Skipper

Severely Dealt with —7. Causewaying of the Streets: The Trustees

Get a Cart Made: Dr. Rennie's Description of the Town and its

Inhabitants—8. The Town in Distress for Want of Water:

Schoolyard Engine Water to be Drained off to Basin—9. Funds to

be Raised by Subscription: Water to be Brought from the Western

Engine: The Water from St. John's Well—10. Herring Curing at the

Seaport: Regulations Prepared : Shipbuilding and Details of the

Shipping—11. Trustees Decide to Erect a Patent Slip: Mr.

Morton's Offer: Subscription Taken and List of Subscribers—12.

Trustees Severely Criticised by Public: Their Reply to

"Misrepresentations and Unmerited Censure" —13. Copy of Town

Accounts for Year Ending 30th May, 1834—14. Trustees their own

Sanitary Inspectors: A Candid Report: Mr. Gillespie and the

"Sewers, Squalor, and Soot" of Bo'ness—15. An Urgent Appeal to

Duke of Hamilton for Assistance: Trouble with People of

Borrowstoun and Newtown over Water—16. The Last of the Water

Trouble: Various Sources Visited and Reported on : Employment of

Mr. William Gale: The Temple Pit Reservoir, Borrowstoun:

Capacity of New Supply—17. The Monkland Railway Brought to

Kinneil: Proposed Extension to Bo'ness: Opposition of Mr.

Goldsmith: His Advisory Letters—18. Summary of Admiralty Report

Ordaining Railway Company to make Promenade Rights in Promenade

Bought by Railway Company.

I.

This second

instalment of early municipal history covers a period of fully

one hundred years. It is only possible therefore to indicate the

principal schemes undertaken by the trustees

The Old Town Hall.

(By permission of Messrs. F. Johnston &* Co.,

Falkirk.)

during that time. Four Acts are embraced, namely,

that of 1769, already referred to, which ran to 1794; one in the

latter year •which continued the term and enlarged the powers

granted under the two previous Acts for the further term of

twenty-one years; another in 1816, again continuing the term and

enlarging the powers of the other Acts for twenty-five years;

and yet another, the largest and most comprehensive of all, not

passed until 1843, which was to continue until repealed. It may

be mentioned that most of the larger schemes undertaken were

duly authorised by these various Acts. The chief feature of the

1816 Act was the power which it gave the trustees to assess and

levy from all occupiers of dwelling-houses, shops, and other

buildings within the town a rate or duty not exceeding one

shilling in the pound upon the rents of such, and to appoint two

or more assessors. This was in addition to the usual two pennies

in the pint, and was for the purpose of defraying the expenses

of lighting, cleaning, and improving the streets and of erecting

a town clock. The 1843 Act, again, changed the method of

election, stipulated for a qualification on the part of trustees

and electors, introduced a declaration when accepting office,

and arranged a rotation or period of service. Moreover, as the

brewing in the town and neighbourhood had become a thing of the

past by that time, the two pennies duty was dropped, and the

trustees for the future were known as "the trustees for the town

and harbour." Under this Act the number of trustees was to be

less than formerly—not fewer than nine and not more than twelve.

It also named the first trustees, and these were Robert Bauchop,

William Henderson, John Taylor, William Roy, John Hardie, John

Anderson, Henry Rymer, James Henry, Henry Hardie, John

Henderson, George Paterson, and James Meikle. Their methods were

much more modern than those of the old merchants and

shipmasters. And while their undertakings were important, yet

the records of these do not leave us with the same distinct

impression of care and capacity in all their work which those of

the "trustees for the two pennies" do. The old trustees were

exceedingly fortunate in having gentlemen of great diligence and

skill as their clerks. We cannot trace all these, but James

Scrimgeour, jun., and David Miln were both in long service under

the earlier Acts, while George Henderson served continuously for

a quarter of a century. A minute, dated the 4th of December,

1820, records—"The meeting takes this opportunity of expressing

their acknowledgments to Mr. George Henderson for his great

fidelity, accuracy, and zeal for the interest of the trust for

upwards of twenty-five years he has held the office of clerk."

Another George Henderson served the Town and Harbour Trustees

with much ability for many years, and carried through all the

intricate negotiations in connection with the extension of the

railway to Bo'ness and other important matters.

II.

Between 1750 and 1780 Borrowstounness was one of

the most thriving towns on the east coast, and ranked as the

third port in Scotland. This commercial activity is reflected in

the minutes, for the trustees were constantly engaged in making

every possible improvement at the harbour for traders. Then, as

now, the continuous mud silt gave great trouble. But in October,

1762, it was resolved to construct a basin for cleaning the

harbour, and in due course the work was carried out by Mr.

Robert M'Kell, engineer. A double wall, moated in the heart, was

run across between the two piers, enclosing about one-fourth of

the harbour at the land side. This contained four sluices.

During spring tides these sluices were regularly opened, and

shut at full sea when a great body of water was retained. At low

water they were opened, and they emptied the basin with so rapid

a current that in the course of a few years a great increase to

the depth of water in the harbour was made. The basin wall was

of similar breadth with the two piers, and gave great

accommodation. From it a middle pier, or tongue, as it was

called, was also built parallel to the other two, so that the

construction of the basin was in every way a great and useful

scheme. Additions were afterwards made to the tongue and the

piers from time to time as necessity arose. It is minuted on one

occasion during the many repairs to the piers that the masons

"are very slothfull in performing their day's work." The

shoremaster therefore was instructed "to oversee said masons two

or three times a day, and if any of them be found idle or

neglecting their work to take a note of their names and to

report them to the trustees as often as they shall be found that

way." At a later date we find the same strict supervision over

the same kind of work—"It is agreed that Daniel Drummond, the

harbourman, shall work as a labourer with the masons, where he

shall be directed during the whole repairs. And if it shall be

found that he attends and works faithfully, and takes care to

make complaint when the other workmen do not their duty, the

trustees mean to make him some little present when the work is

finished."

In 1769 it was found necessary to repair the

streets, and £30 was allocated thus—£6 on

the east pier, and £6 on the west pier, to pave it down to the

basin wall; £8 from

the church westward; £5 at

the east end of the town; and £5 where found necessary. Dr.

Roebuck, Robert Hart, and John Pearson were to see that the work

was properly executed.

III.

For several months onwards from June, 1772, there

is much to be found about the construction of the waggon road.

Dr. Roebuck's affairs were in the hands of his trustees,

Mansfield, Hunter & Co. They recommenced operations at the

coalfield, and John Allenson and John Grieve were their local

managers. Evidently some pits on the hill were then opened, and

the doctor's trustees wished to have a waggon way down the Wynd

and along the shore to the west pier for the shipment of the

coal. This presented the town trustees with several excellent

opportunities, and they did not fail to seize them. They were,

as it is written, "much disposed to accommodate Dr. Roebuck's

trustees, so that they might not be obstructed in prosecuting

their coalwork business." So they consented to the construction

of the waggon way, but upon certain important terms and

conditions. One of these was that a new street from the Wynd to

the harbour should also be formed. Everything was to be done to

the satisfaction of a special committee consisting of John

Walkinshaw, Robert Hart, Alexander Buchanan, John Pearson, and

John Cowan. The doctor's trustees, of course, were to bear the

whole expense, including the paving of the new street with

Queensferry stones "by proper bred pavers." It was thought that

some of the houses at "Kirkyard Wynd foot" might be damaged in

rendering entry to them more inconvenient. For these and all

other claims which might arise out of the construction of the

new street and the waggon way the town trustees were to be

freed, and an agreement in these terms was entered into and

carried out. The scheme was beset with difficulties, the chief

of which was the crossing of the old street at the foot of the

Wynd. Here and elsewhere the waggon way was to be 3 or 4 feet

above the street level, and it was to be safely "finished off."

The trustees thought that it would end at the head of the west

pier, and considerable consternation prevailed when they found

Allenson and Grieve proceeding with it down the pier. Such, it

was thought, would prove very prejudicial to the trade of the

town "by making it impossible for carts carrying down and up

goods from passing each other." It was discovered also that each

waggon ''is to carry about three tons of coal, which is about or

near to double the weight that Dr. Roebuck's waggons formerly

carried." The matter was adjusted, however, by allowing the

railway to proceed, "the trustees of the doctor to stand bound

to the town trustees and their successors in office to answer

for and make good every damage whatever that might then or in

the future be done to the pier in consequence of the railway."

All this was come to after grave deliberation;

and the reason for the consent was because " the trustees of the

harbour are perfectly disposed to indulge Dr. John Roebuck and

his trustees to the utmost of their power consisting with the

duty they owe to themselves and the public, being much convinced

that the success of the coalliery of this town is perfectly

connected with the trade and prosperity thereof."

IV.

Petitions from the inhabitants desiring redress

of various grievances were frequent. While the new street was

being made the Rev. Mr. Baillie and others craved that the road

called Providence leading into the south part of the town "might

either be made as it was before, or that the coal managers be

ordained to throw a bridge across the waggon way, so that the

said Providence Road may be rendered passable as before for

leading the grain to the barnyards and other goods to and from

the town." Mr. Grieve, on being sent for, agreed, "in presence

of the meeting," to execute the bridge forthwith.

Another petition was received representing the

ruinous situation of the "Syver Well," and praying that it might

be properly repaired and a pump put into it. The trustees

consented, and appointed Mr. John Cowan "to write to Mr. Sylby

at Edinburgh, or any other proper person, to know at what

expense the same can be done, and agree therefor, so as the town

may be supplied in this necessary article of life in the most

commodious manner." Mr. Sylby's estimate of £i 10s. was

accepted, and it was further resolved to have the well built in

with large stones.

Shortly after this Charles Addison & Sons craved

that a second pump be put in at the Syver well for the purpose

of supplying their brewery, the water to be filled with a cask

and & cart. The inhabitants petitioned against this, and set

forth the inconvenience that would arise to them if a second

pump was put in the"well for "shipping water in carts." The

trustees refused the request, but arranged that a pump should be

erected at the Run Well instead. With reference to the Addisons,

it is of interest to know that the large property to the north

of Market Square, which was burned down in 1911, was built by

Charles Addison. His feu charter of the ground was granted by

James sixth Duke of Hamilton on the 20th of September, 1752. The

narrative runs—"Whereas Charles Addison, merchant in my burgh of

Borrowstounness, hath already expended a considerable sum of his

own proper money in gaining the area aftermentioned from off the

sea (upon which there were never any house or houses built, and

which never yielded any rent or profite to me or my

predecessors), and in building a strong buttress or bullwork of

hewen aceler fenced with many huge stones for the support

thereof,, and will be farder at a very great expence in building

a dwelling-house, office houses, cellors, proper warehouses, and

granaries on the said area or shoar of the said Burgh, which

works were undertaken and are carrying on by him upon

the-assurance of his obtaining from me a grant of the said area;

Therefor and for his encouragement to compleat so laudable ane

undertaking which tends to the advancement of the policy and

trade of the said town," and in consideration of his paying a

yearly feu-duty and on several other terms and conditions, the

reclaimed ground referred to was granted him. The boundaries of

the ground so feued are given as the sea on the north; the

houses of Mary Wilson on the east; the High Street on the south;

and the easter pier and highway leading to the same on the west.

V.

To return to the petitions, another is referred

to thus— "The trustees have laid before them a petition from the

inhabitants of this town setting forth that the streets are

exceedingly dirty and hardly passable, particularly at the

easter coalfold opposite to Taylor's pit; also at Margaret

Shifton's. door, where the water often collects so as to render

the passing difficult, and even so as to endanger the health of

the inhabitants; from colds and disorders in consequence of wett

feet." Though they had power under the Act to keep the streets

in order and " open the avenues to the town," yet the want of

funds prevented their doing so. These funds were, in the first

place, to be applied to the improvement of the harbour, and it

alone exhausted the whole. In order to give them funds so that

the requests in the above and other petitions might be attended

to, the trustees resolved to "lett to publick roup" the whole of

the street manure of the town. Meantime the collector

was-instructed to employ a carter and a raker to cart it away.

He-was also to give notice by the drum on every market day, till

2nd November, 1772, of the intended roup. William Robertson,

James Tod, Alexander Buchanan, John Paris, and John Cowan were

appointed to make proper regulations "as to the way and; manner

of carrying off the dung." The roup was adjourned from the 2nd

to the 9th, "on account of the badness of the weather." No

bidders appeared at the adjourned roup, except Charles Addison,

jun., who offered 5s. for the whole for the-half-year to

Whitsunday. The trustees refused this, but offered to take half

a guinea, and Mr. Addison agreed. In course of time this came to

be a source of considerable revenue. In 1783 the bye-ales alone

were exposed, and John Drummond, as the-last and highest bidder,

was preferred at the sum of £27 for the year to 1st July, 1784.

He failed to pay, and the trustees, got decree, and had him

imprisoned. Meanwhile he had gone "and declared himself bankrupt

on oath, in consequence whereof' the Bailies of Linlithgow

allowed him an aliment of 7d. per day." His two cautioners

attended a meeting, and the trustees, considering the hardship

of their situation, agreed to their proposal to pay by two

half-yearly instalments, provided they found a sufficient

cautioner in a fortnight. Then the minute-continues—"As the

meeting see no good reason for alimenting-John Drummond, they

resolve not to do it," and they left it to-his cautioners to act

in the manner as they saw cause. In after years we find that

John Black was almost a regular purchaser of the tack of the

bye-ales and also of the street manure, and it would thus seem

he had found them profitable-concerns.

VI.

To go back a little, we find James Baird, the

shoremaster,. reporting on the 8th of March, 1773, that Charles

Baad, master of the sloop "Venus," had come into the harbour on

Saturday with ballast, and, " contrary to the practice of all

harbours and: of all law," had thrown it out late on Saturday

night off the-head of the harbour. Band compeared and denied

that he brought in any ballast, upon which the trustees called

in John Thomson, workman, and put him on oath. He deponed that

he was sent on board to get "a parcell of wands" for Dr. Roebuck

& Co.'s coalworks; and that he saw a "parcell of ballast"—about

twenty carts and upwards. By mid-day the wands were all taken

out of the sloop, and Baad engaged him to come about eight

o'clock at night, when it was dark, to assist to throw out his

ballast. The sloop had been hauled off about a cable length

north of the west pier, and between eight and nine Baad took him

off in his small boat. When he got aboard he found Daniel

Robertson, carpenter, and Baad's own men busy throwing the

ballast overboard. He then commenced to help, and it was all out

in about an hour.

Daniel Robertson, being also called in and sworn,

corroborated. The trustees found it clearly proven that,

contrary to the regulations, Baad had, "when dark, thrown over a

considerable quantity of ballast off the mouth of this harbour,

to the great hurt and prejudice thereof," and decerned him to

pay "Ten pound sterling for this trespass." If he failed to pay,

the sloop was to be distressed "by carrying off as many of her

sails as when sold will amount to the sum of ten pounds, with

all charges of every kind." They had some difficulty in getting

the fine, but after taking possession of the sails the money was

paid.

VII.

On 9th December, 1776, the trustees had before

them a petition signed by William Anderson and James Dalgleish,

merchants, and a good many other inhabitants, once more

complaining of the great inconvenience that arose from the water

lodging at the street opposite to Margaret Main's door at

Taylor's " pitt," and praying the trustees to remedy the same

T>y opening a water passage across the street. Mr. Cowan, to

relieve the situation, gave leave to lay an open sewer across

the timber yard possessed by him opposite to that part of the

street complained of, and, as usual, a committee was appointed

to see the work done. At the same time, the committee were

empowered "to agree with causewaymen or others to execute the

necessary work near to Margaret Main's house, and also to repair

several broken parts of the street, namely, at Robert Beaton's

door—John Mitchell's door—opposite to the Syver Well—opposite to

Margaret Shifton's door—near to Mr. Thomson's, watchmaker—near

to Widow Mackie's house—near Captain Hunter's house—near Mr.

Edward Cowan's house, with several other small broken places of

the streets and vennels." Towards the end of the period under

review we find in the minutes a "copy of specification for

making a cart for taking the fulzie off Bo'ness streets." All

the parts are specified carefully, and the wealth of detail

given is amusing. The contractor was taken bound to uphold

workmanship and material for the space of twelve months after

date of furnishing, which was to be within fourteen days after

acceptance of estimate. James Meikle, William Marshall, and J.

M. Gardner were appointed to get estimates and to accept the

best.

Dr. Rennie describes

some of the houses about this time as being low and crowded, and

bearing the marks of antiquity. For the most part, however, they

were clean and commodious. The smoke from the coalworks was a

great nuisance, and continually involved the town in a cloud.

Houses were blackened with soot, the air impregnated with vapour,

and strangers were struck with the disreputable appearance of

the place. But these nuisances were being removed from the

immediate vicinity to a considerable distance, and more

attention was being paid to cleaning the streets. Still, the

smoke from the Grange coalworks on the east, the Bo'ness

saltpans on the west, and the dust excited by the carts carrying

coals to the quays for exportation occasionally inconvenienced

the inhabitants. Crowded as the houses might appear to a

stranger, no bad consequences were felt. Ordinary diseases were

not more frequent here than in other places. In fact, health was

enjoyed to a greater degree in and around Bo'ness than in many

towns of its size and population. This was accounted for by the

fact that the shore was washed by the Forth twice every

twenty-four hours. Moreover, the vapours from the saltpans

corrected any septic quality in the air. The walks about the

town were romantic and inviting; the walks on the quays and on

the west beach were at all times •dry and pleasant, and greatly

fitted to promote health and longevity. Unfortunately, however,

tippling houses were too numerous. It was to be seriously

regretted that too many people were licensed to vend ardent

spirits in every town and village. Such places ensnared the

innocent, became the haunts •of the idle and dissipated, and

ruined annually the health and morals of thousands of mankind.

Perhaps if the malt tax were abolished, and an adequate

additional tax laid upon British spirits, as in the days of

their fathers-, malt liquor would be produced to nourish and

strengthen instead of whisky, which wasted and enfeebled the

constitution; or were Justices of the Peace to limit the number

of licences issued by apportioning them to the population of

each place and by granting them to persons of a respectable

character, a multitude of grievances would be redressed. Writing

of the inhabitants, Dr. Rennie •states that they were fond of a

seafaring life. Many able-bodied seamen from the town were in

His Majesty's service, and were distinguished for their

sobriety, courage, and loyalty. Adventurers from the town also

were to be found in the most distant parts of the globe. On the

whole, the inhabitants were in general sober and industrious,

and were of most respectable character.

VIII.

The water supply of the town has been a subject

which has given much anxiety to the municipal authorities since

about the end of the eighteenth century, and has involved the

expenditure of very large sums of money. In early days the worry

was not that there were no water sources in the neighbourhood.

On the contrary, there were natural springs in abundance

containing water of an excellent quality. Coal mining

operations, however, diverted nearly all these from their

original channels. The Act of 1769 gave the trustees power to

contract for springs and build reservoirs, but there were no

funds. Petitions and complaints were frequently lodged, and in

June, 1778, it is minuted—"Almost the whole town is in great

distress for want of fresh water, which has of late become

exceedingly scarce." It was therefore resolved to get estimates

from properly qualified surveyors to bring water to the town

through lead pipes, earthen pipes, or through wooden pipes.

William Robertson, Alexander Buchanan, and John Cowan were

appointed a special committee to get these. The expense, of

course, was a great obstacle, for the trustees " did not at all

understand that they as trustees were to pay the sum that might

be found necessary for bringing water into the town, which they

know no way of doing but by a voluntary subscription, with such

aid as His Grace the Duke of Hamilton shall please to give."

They, however, agreed to pay the expense of such plan if it did

not exceed £5 5s., "and to be as much less as they can." But a

few years were spent in getting the estimates, and meantime the

trustees had to deal with other water affairs. For instance, it

was stated at a meeting in September, 1781, that water might be

had to supply the town about a hundred yards south of Mr. Main's

park, immediately to the south of the town; and a committee

consisting of Dr. Roebuck, John Cowan, and some others was

appointed to investigate the matter. They did so, and got

estimates of what it would cost to bring the said water in an

open ditch from near Graham's Dyke down to the meeting-house by

way of a trial. The offer of Charles St. Clair or Sinclair was

accepted, and the committee was continued to see the work

executed. Then, again, the water from the schoolyard engine

caused "great damage to sundries," and it was resolved to obtain

an estimate " for carrying that water into the bason by a level

under the street and by the shortest line." Estimates were

produced at next meeting from Charles Sinclair—one for £30 5s.

lid., and the other for £22 5s. lid. in another way; but the

trustees wished to go further into the matter, as it was

considered " of some consequence not only as to the convenience,

but even as to the health of many of the inhabitants,

particularly the younger part, such as school boys, &c., that

this hott engine water be carried off in the best and most

expeditious manner through and across the streets into the bason

or into the sea in the way that shall be reckoned best for the

inhabitants in general."

IX.

To bring this about they thought it necessary to

appoint a committee consisting of Dr. John Roebuck, James Tod,

James Main, James Drummond, and John Cowan, three a quorum,

"with power to them to examine, deliberate, and determine on the

tract that is reckoned the best." It was further resolved to get

a subscription opened for making up two-thirds of the sum

wanted, the trustees agreeing to pay the other third. And in

case the inhabitants fell short of subscribers for the

two-thirds, including what might be given by His Grace the Duke

of Hamilton, another meeting of trustees was to be called to

consider if they could contribute any more than the one-third.

The trustees met on 8th November, 1781, under the

presidency of Dr. Roebuck, to consider the plans, estimates, and

surveys for bringing water to the town in lead pipes and in

wooden pipes, to be brought from Torneyhill, from St. Johns, and

from the Western Engine. The meeting was of opinion that funds

could not easily be raised to bring the fresh water from any of

those places in leaden pipes, and they were of opinion that

wooden pipes would be insufficient. Mr. Charles Sinclair

estimated the cost of getting the water brought from the Western

Engine in wooden pipes at £187, which was considered reasonable,

and they unanimously approved thereof, and agreed to contribute

the sum of £30 towards it. Mr. James Drummond was appointed to

meet with the water subscribers of the town, and to communicate

to them the resolution of the meeting.

An important step in the progress of the water

question is recorded in a minute of meeting dated the 9th of

December, 1818. There were present Robert Bauchop, John Taylor,

William Henderson, George Hart, Walter Grindlay, James Tod,

Thomas Johnston, John Padon, Andrew Tod, James Johnstone, Ilay

Burns, and Thomas Cowan. The committee appointed to superintend

the bringing in to the town of the water from St. John's Well

then reported that the pipes were now completed to their

satisfaction, and that the well at the Cross was also finished.

They were glad to say that the supply of water proved to be

fully equal to the wants of the inhabitants. The committee also

produced the New Shotts Iron Company's accounts, amounting to

£218 10s. 4d., of which £38 9s. 4d. was the cost of the new

cistern and well at the Cross. This had been found necessary

after making trial of a less expensive mode of delivering the

water, which, however, did not succeed owing to the very great

pressure of water from the reservoir to the town.

X.

Quite unexpectedly the Forth herring fishing,

hitherto unknown in this part, was so successful during the

season 1794-5 that hopes were entertained that herring curing

would be added to the industries of the place. We discover

evidences of this in the minutes. The trustees thought that the

herring vessels which then occupied the piers should be made to

pay a small allowance for the use of these, and also to meet the

necessary repairs which carts with a great weight of fish would

occasion the buildings. If "little ordinary trade was going

forward," they admitted, the use of the piers could be permitted

with little inconvenience. But "if trade otherwise was brisk,"

the herring curing would prove a great obstruction. In this

view, it was right the herring vessels should pay a little. At

the same time, they wished to do this " so gently as not to make

£he busses avoid the harbour." The trustees, indeed, were very

cautious, "this being the outset of a new business," and they

were anxious not to discourage its development. A committee of

three was therefore appointed to inquire into the practice and

mode of charge in other places where the piers were so used, and

to draw up such regulations as appeared to

R them

adequate before the return of the next

fishing season. On 3rd August, 1796, a meeting was called to

consider the report and draft of proposed regulations of the

committee. The regulations consisted of five clauses, "and with

a small addition to the sixth and a slight alteration at the

commencement of the seventh, unanimously adopted them, and

returned - their thanks to the committee for the pains bestowed

on this subject."

We can only briefly indicate these "Regulations

for the curing of herrings at the harbour of Borrowstounness."

The persons in charge of all "busses" or herring vessels on

entering the harbour were to state whether they meant to cure

any of their fish upon the quays. If so, they were to be charged

4d. per ton register for the privilege in addition to the

anchorage duty. If no notice was given, and herrings were found

on the quays beyond the space of forty-eight hours, they were to

be seized and sold, and the proceeds converted to the use of the

harbour. If any vessel did not cure to the extent of her full

loading, the person in charge, on making testimony of the

reason, was to receive a return of such part of the curing dues

as the collector thought fit. Those not having vessels, but who

might purchase herrings and cure them on the quays, were

likewise subjected to the payment of dues, six barrels to be

reckoned as equal to a ton register. Very unfortunately the

herrings never returned to this part of the Firth in any

quantity, and so the careful preparations of the trustees to

foster the "new business" and at the same time to increase the

harbour revenue proved futile.

Shipbuilding was engaged in on a fairly extensive

scale at Borrowstounness from about the middle of the eighteenth

to the middle of the nineteenth centuries. Towards the end of

the former there were two builders of note—Robert Hart and

Thomas Boag, and the vessels built were from 300 to 350 tons

burden. The Grays from Kincardine came later, and the last

builder on the ground was one Meldrum. He built a ship called

the "Ebenezer" and another called the "Isabella."

The shipping2 belonging

to the town at this time consisted of twenty-five sail, 17 of

them being brigantines of from 70 to 170 tons per register.

Eight were sloops from 20 to 70 tons per register, and

altogether the shipping employed about 170 men and boys. Of the

brigantines six were under contract to sail regularly once every

fourteen days to and from London. They were all fine vessels,

from 147 to 167 tons per register. The remaining eleven

brigantines and also one of the sloops were chiefly engaged in

the Baltic trade. The other seven sloops were for the canal and

coasting.

XI.

We have seen how anxious the trustees always were

to improve and extend the trade, and therefore we are not

astonished to find that in July, 1781, they saw "of what great

utility the having a dry dock properly executed in the bason

would be to the trade and commerce of this town." They agreed to

meet again in a fortnight "to consider this very essential piece

of business," Dr. Roebuck and Mr. Cowan meantime to procure

plans and estimates. The proposal, however, fell through, but

was not entirely lost sight of. About forty years after it was

still thought necessary that either a dry dock or a patent slip

be erected for the purpose of repairing ships. After full

consideration, the trustees decided to erect a slip, as in their

view it would answer the purpose better and cost less money.

On 11th September, 1820, it was reported that a

letter had been received from Mr. Thomas Morton, Leith, offering

to execute the slip, with all its appendages and necessary

excavation and building, for £865. As this sum was not at the

disposal of the trustees, they proposed to make a public

subscription. Each trustee promised to exert himself to procure

the sum required. Mr. Morton was requested to guarantee the work

for two years, and to extend the size of the slip so that it

might be capable of taking vessels up to 360 tons register. Mr.

Morton's offer, however, was not to be accepted until it was

seen what subscriptions were obtained. By 4th December the

Harbour Committee reported that subscriptions to the amount

required had been received, and the meeting accepted Mr.

Morton's offer. This slip was the second of the kind he erected

in the country.

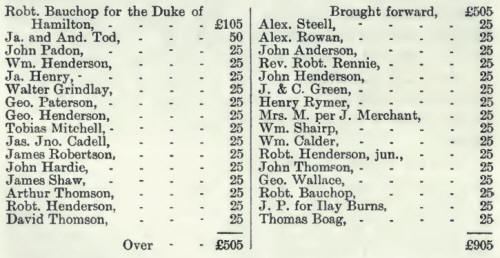

The following is a copy of the subscription list

as recorded in the minutes, with a note of the conditions on

which the slip was to be held. It was to be the joint property

of the subscribers; the subscriptions were to be paid as soon as

the work was completed and fit for use; the rates for the use of

the slip were to be fixed by a majority of the subscribers, who

were to vote according to their shares of £25 each vote. The

Harbour Trustees were to maintain the gate and the basin wall,

and the harbourmaster was to take charge of the slip and collect

the dues thereof. In consideration of all this and of the money

already expended towards the accommodation of the slip, one-half

of the revenue arising from it was to form a part of the town's

funds after deducting the rent of that part of the premises

taken by the trustees from the Duke of Hamilton.

The slip did not turn out a success, largely

owing to the falling fortunes of the seaport about that

time. And as the Rev. Dr. Rennie used to say, it certainly

proved a slip, for it did not pay any dividend.

XII.

As we have said more than once, the affairs of

the town and harbour were well managed. Nevertheless, the

actions of

the trustees were carefully watched and sometimes severely

criticised by various members of the community. This was

particularly the case in December, 1825. At a meeting of

trustees held on the 12th of that month a long letter or

memorial representing certain alleged grievances was submitted.

It was subscribed by John Stephens, Peter Petrie, Thomas Boag,

Arthur Thomson, Thomas Collins, Robert Boyd, and George Wallace.

These parties stated that they had consulted the Sheriff of the

county about their grievances, and had been advised by him to

apply directly to the Lord Advocate. Before taking this step,

however, and in the hope of rendering it unnecessary, they

thought it expedient to submit their complaints direct. They

hoped the trustees would consider them attentively, and grant

what they believed was the general wish of the inhabitants of

the town. Shortly put, their grievances were—(1) The want of a

sufficient supply of soft water, and the deficiency of wells. As

a cause of the deficient water supply, it was stated the

diameter of the water pipes was completely inadequate to the

consumption of 630 families. Seven years had elapsed without any

effectual steps being taken to remedy the evil, and, although

the assessment had been increased, they were not aware that it

was the intention of the trustees to apply it to this most

necessary purpose. (2) The assessment had not been imposed in

terms of the Act on proprietors occupying their own houses. (3)

That the specific, and consequently the primary, purposes for

which the power of assessing was granted by the Act had been

totally disregarded, and the intentions of the Legislature for

the good of the town entirely frustrated. The last, although

perhaps the most direct violation of the statute, was what the

complainers were disposed to insist least upon. Lighting the

streets and a public clock, however desirable, were not to be

compared with that essential necessary of life, an adequate

supply of good water. Their request therefore was that the

trustees would devote the assessment solely to the supplying of

all parts of the town with water, that they would cause pipes of

a sufficient size to be laid from St. John's Well to the

reservoir, that they would leave a branch pipe at the corner of

the school area for the accommodation of the scholars and of

nearly thirty families residing in that quarter (a great

proportion of whom were old people, and very unable to carry

water up the hill), and that they would cause two additional

wells to be erected for the benefit of the east and west ends of

the town, and adopt such regulations as would prevent any of the

water from being carried out of the parish. They concluded by

stating that if the trustees refused their requests, they would

feel it a duty incumbent on them to resist payment of the

assessment, and to seek redress in a higher quarter.

The trustees greatly resented the tone and temper

of this memorial, and especially the threat to appeal to the

Lord Advocate. Seven very lengthy resolutions were adopted by

them by way of reply, and the meeting authorised the clerk to

send Mr. Stephens a copy of them for the information of himself

and the other complainers. They also ordered two hundred copies

to be printed and circulated amongst the inhabitants. The

substance of their defence amounted to this—It was quite

erroneous to say that the house assessment had been laid on for

the special purpose of supplying water. On the contrary, as they

specially pointed out, the Act authorising its imposition did

not so much as mention the water question. They claimed that

they were as much interested as any one could be in the town

having a good water supply. Since 1816, they stated, no less

than £432 lis. 4d. had been expended for that purpose, being

upwards of £100 more than the whole sum yet levied by

assessment. They also fully explained their present financial

position, and what led up to it, and closed thus: — " The

trustees conclude by remarking that they have long suffered in

silence the misrepresentations and unmerited censure of those

who are more ready to find fault with than to aid them in the

service of the public. But now that a formal complaint is made,

they deem it only doing justice to themselves to submit this

explanation to the candid consideration of the inhabitants at

large."

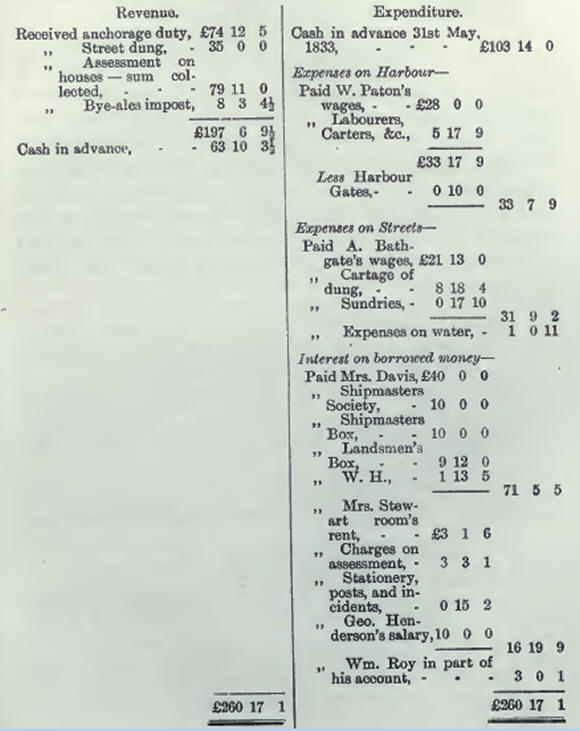

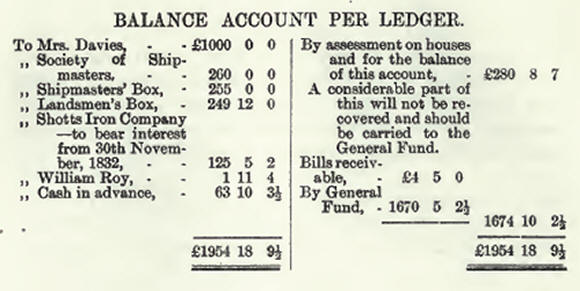

The following is a copy of the annual statement

of trust funds submitted by Mr. William Henderson for the year

ending 30th May, 1834. When we compare this short and simple

document with the elaborate annual volume of 80 folio pages

which is now its successor we rub our eyes indeed.

XIII.

XIV.

The trustees of the town and harbour were their

own sanitary inspectors. Below we give extracts from the report

of a special committee, which, along with the Parochial Board,

inspected the whole town in October, 1848. Their methods were

thorough, and they called a spade a spade. They found the

following : —

Gardner's Land—Horrid.

King Street—A yard and closed door heaped with

filth from the windows and two dunghills.

Peebles' pigstye—Bad; his cellar ought to have a

door or built up.

Beneficent Society's Land—Bad drain, dunghill,

and nuisance.

Slidry Stane—A noxious drain.

Wilson's house at Slidry Stane—One continued mass

of filth.

John Marshall's property—Horrid.

Providence stair—Three dunghills.

Mrs. Peddie's backdoor—The yard wants paving; two

ugly dunghills.

Robertson's dunghill, &c.—Disgusting.

Mrs. Wallace complains of two pools in the

foundry yard below her bedroom window.

Walker, butcher, kills at his shop, also

Stevenson, in his shop.

The Duke of Hamilton's property at the east end

of Corbiehall is in a most wretched condition, as the whole of

the Duke's property here is, without exception. Would recommend

the whole of the Duke's property to be divided into sections,

say, of four or five families each.

Nimmo obstructs the pen close with his carts.

Boslem's house ought to be whitewashed.

These things do not make pleasant reading, and

with the smoke of the saltpans and coalpits, they undoubtedly

combined to give the seaport the unenviable reputation of being

a "terribly dirty place." But it would be an entirely unfounded

statement to make now. It was, we think, even a bold thing to

say in 1879,3 when

Mr. Gillespie wrote about the "sewers, squalor, and soot" of

Bo'ness. We may as well hear him out— "Bo'ness, as we have said,

is both dull and dirty. Its situation, for one thing, is very

low, which militates against its sanitary interests. It is

ill-constructed and worse kept; each narrow, crooked street is

in a more neglected condition than its neighbour; and the

authorities apparently leave everything to the laws of Nature,

not thinking it part of their business to make the place clean,

healthy, or sweet. The architecture is said to have been once

admirably described by an old gentleman with the aid of a

decanter and a handful of nutshells thus— ' You see this

decanter; this is the church.' Then taking the shells and

pouring them over the decanter, he said, ' And these are the

houses.' Nothing could be truer. There is not one regular street

in the town. The poor lieges, too, have the same wretchedly '

reekit' appearance as the place itself. And thus, looking at

Bo'ness with its back to the wall, it is strange to think of it

as a proud Burgh of Regality. With the exception of the

queer-looking old church, it has not a house that would do

credit to the humblest clachan." No doubt Bo'ness was at that

time in a pretty low way. It was practically stagnant, and grass

grew in some of the streets. Mr. Gillespie termed it a condition

of comparative indigence. But he was good enough to herald the

approach of brighter and better days, in view of the

"enterprising and important works being carried out in the

extension of the harbour and the construction of a dock."

XV.

We must return, however, to the minutes. There

are frequent references throughout these to letters and appeals

to His Grace the Duke of Hamilton. We can only mention one,

which was in the form of a petition, and the most appealing of

all. It was apparently presented at Hamilton by a deputation

from the trustees, consisting of John Anderson, Archibald

Hunter, Peter Mills, and George Henderson, their clerk. The date

of the document is 19th October, 1848, and is signed by Mr.

Henderson, "your Grace's faithful and devoted servant." He

acquainted His Grace—(1) That the streets in many places were

very narrow and wretchedly paved, and susceptible of repair,

alteration, and improvement. (2) That the town was most

miserably supplied with water in consequence of the mineral

workings drawing off the chief supply. Also that the inhabitants

were unable to obtain anything like an adequate supply of fresh

water for domestic purposes even by standing their turn for

hours at the public wells of the town. This annoyance to the

inhabitants was the source of many unseemly brawls and disputes.

And the want of a copious water supply was clearly standing in

the way of the improvement of the sanitary condition of the

town. (3) That the authorities and people of the town were

without any proper place in which to meet for the discussion and

discharge of the town's business, nor was there a hall or public

room in which a public meeting of the inhabitants could for any

useful purpose be convened.

Coming to financial affairs, Mr. Henderson points

out that the trustees were deeply in debt, the arrears of many

years. They had not money to meet the ordinary expenditure

required for the town and harbour. They had not the means to

pave and improve the streets. They could not afford a better

supply of water to the inhabitants, and they could not provide

public buildings. In this dilemma they applied to His Grace for

assistance. And they respectfully suggested that the case would

be met by granting to the town at a merely nominal rent a lease

of the Town's Customs and the building called the Town House

(part of which is presently used as a county lock-up, a large

portion still remaining unoccupied). This favour, he was sure,

would go far to enable the trustees to execute the improvements

so much required, and would confer a lasting benefit upon the

inhabitants.

The Duke was good enough to comply, and he and

his factor gave every assistance in connection with the

endeavours of the trustees to increase the water supply.

In October, the following year, "the people of

Borrowstoun and the inhabitants of Newtown" resented some

operations connected with the cutting of deep drains at

Borrowstoun, by which the trustees "had every prospect of

materially increasing their water supply." They therefore wrote

to Mr. Webster, the Duke's factor, to use his influence to stop

this interference and to assure the people that the trustees had

no intention whatever to deprive the Borrowstoun people of their

supply of water. On the contrary, they wished to improve it both

for them and the town of Bo'ness. For this purpose they proposed

to considerably enlarge the fountain of St. John's Well, which

was to be properly enclosed, and a pump put into it for the use

of the inhabitants of Borrowstoun.

XVI.

The last phase of the ever-recurring water

question which comes within our notice here is by far the most

important. From 1846 to 1852 the trustees were almost constantly

engaged, sometimes unaided and sometimes with the assistance of

experts, in visiting and reporting upon various suggested

sources for a new and enlarged supply. They examined two springs

in the neighbourhood of Inveravon, the first called Langlands

and the second Cold Wells. Both were found highly satisfactory

in quality and quantity. No heavy cuttings were required for

•either. A spring on the lands of Balderstone was also visited,

and found suitable in every way. In fact, the committee of

inspection unanimously recommended the trustees "to turn their

attention to this quarter, being so much nearer to the town, as

well as to the pipes which bring the present supply." The method

of bringing the water over the hill was by "the plan of a syphon."

Mr. Wilson, of Kinneil Ironworks, was next approached for a

supply of pit water from the Snab pit. He was quite agreeable to

give this. The water was to be filtered, and a pond was to be

constructed near the east side of that field above the

distillery and south of Mr. Yannan's garden. In the midst of

these inquiries the trustees received a letter from James

Dunlop, Braehead, with " a short and simple" •suggestion. This

was that the Dean or Gil Burn, where

"a reservoir was formed by Nature capable of containing a

quantity of water sufficient to supply in the most complete

manner throughout the whole year the inhabitants of Bo'ness. It

is -excellently suited either for culinary or cleansing

purposes, and far superior for the latter purpose to your

present supply from St. John's Well." He also pointed out that

the quality of the water from the Snab pit was very hard, and

very likely would soon become salt or brackish. His suggestion,

he ventured to think, was a most useful one, and he hoped the

trustees would take the trouble to examine the site. They did

so, but considered the plan " quite ridiculous." A resolution

was then made to adopt the Snab pit scheme, but it was negatived

by a majority of one vote. Mr. Webster, the Duke's factor, took

a great interest in the Cold Wells scheme, and obtained

estimates for bringing that supply to the town. These amounted

to £1000, but the scheme was abandoned as being far beyond the

resources of the trustees even with the aid of a public

subscription. The Snab pit water was once more pushed for a

while, and Mr. Hall Blyth, C.E., Edinburgh, was engaged. After a

time, however, the idea was finally abandoned. The engineer who

at last relieved the minds of the trustees, after many visits

and the preparation of many specifications, was Mr. William

Gale, C.E., Glasgow. He was introduced to the trustees through

Mr. Robert Steele, of the Bo'ness Foundry Company. Mr. Gale was

stated to be eminently qualified for such an undertaking, and

was more employed in bringing water into towns by gravitation

than any other engineer in Scotland. The site ultimately fixed

on was known as the Temple pit at Borrowstoun. Much interest was

taken by the inhabitants in the selection of the site and mode

of construction. A public meeting was held, and a special

committee of the inhabitants, consisting of William Simpson,

James Gray, and Robert Morris, kept in close touch with the

movements of the trustees. They especially gave great assistance

with the public subscription lists which were opened. These were

"not confined to proprietors or any other class, but open to all

holding property in or otherwise connected with the town, or

having an interest in its welfare, whether residents or not."

The resolution to proceed with the Temple pit reservoir was come

to at a meeting of trustees held on 14th April, 1852. Those in

office at the time appear to have been John Anderson, John

Henderson, John Marshall, James Meikle, James Kirkwood, John

Taylor, Peter Mills, Henry Rymer, James Jamieson, William

Millar, Robert M'Nair, and William Donaldson. The contract was

advertised, and fourteen tenders were received, mostly from

Glasgow. The joint offer of Allan Henderson and George Gray was

accepted at £158 4s. 2£d., being the lowest. Some of the offers

were more than double that figure. The work was completed

towards the end of the year. Mr. Alexander Gale was inspector,

and in a long report made to the trustees in October we find

this information: —"As now completed, the reservoir will contain

182'900 cubic feet, or 1,143,100 gallons. Taking the population

of the town at 3000, this would keep up a supply of 5 gallons

per day for seventy-six days, independent of any supply from St.

John's Well or any casual shower that may fall during that

time."

XVII.

The establishment of the Kinneil furnaces by Mr.

John Wilson, Dundy van, resulted in the Monkland Railway

constructing a single line to Kinneil for goods traffic. It was

opened on the 17th of March, 1851, by a trainload from Arden for

the ironworks. And it is almost of romantic interest to know

that the engine of that train was in charge of Mr. William

Thomson, who afterwards became a successful merchant and Provost

of the seaport. The extension of the railway to Bo'ness was the

next 6tep, but it was a serious thing for the town in one sense,

for it meant the probable destruction of the west beach and the

Corbiehall foreshore. The trustees were fully alive both to the

numerous advantages which the extension of the railway would

give, and also to the curtailment of public rights which were

involved. Their minutes at this period are full of many

interesting items, and contain a lengthy correspondence with the

railway company, the Admiralty, and others. A Mr. J. H.

Goldsmith appears to have been the people's champion. His

letters are dated from Bo'ness, and he writes as if he were a

member of the legal profession. But who he was we have been

quite unable to discover. On the 13th of January, 1851, he wrote

the trustees pointing out " the great and manifest injury which

the inhabitants would suffer at the hands of the Slamannan and

Bo'ness railway now constructing." These evils, he stated, might

have been avoided by compelling the company to carry their

railway on arches to its terminus. The west beach and western

foreshore were then, we believe, much lower than now, and at the

time Mr. Goldsmith wrote it would seem that the railway could

easily have been led in as he suggested, on a long viaduct, thus

leaving free access to the shore as hitherto through its arches.

What, he continues, the inhabitants required, and had a right to

demand at the hands

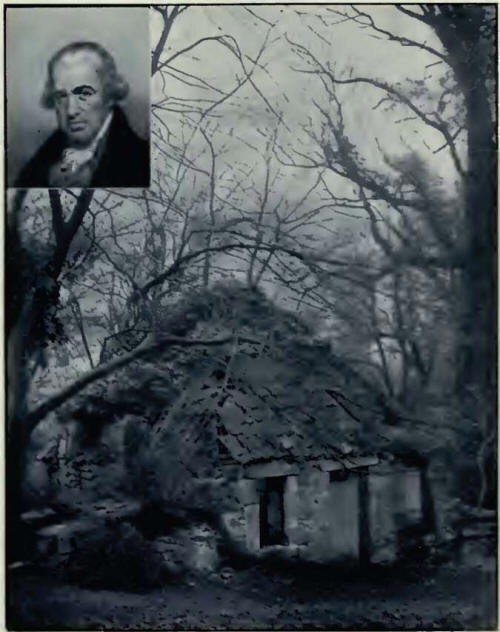

James Watt and his Outhouse at Kinneil.

(From a photograph by David Grant, Bo'ness.)

of the trustees, was their ancient bleaching and

bathing ground, and the " freest possible unimpeded ebb and flow

of the tide." Should they be unfortunately deprived of these

rights compensation by thousands, not hundreds, should be sought

for by them and obtained. Was it too late, he asks, to repair

past inactivity by immediately sending a deputation to London?

He trusted that the ill-advised stipulation for the building of

three bridges did not give the power to fill up and make land

between the railway and the waggon way. If it did not do so they

had a good case, and their present negotiations might be broken

off. They thus would have a fair field to begin de

novo.

It had been resolved by the trustees that their

resolution asking for £1000 for servitude rights on the beach

should first of all be sent to Mr. Thomas Stevenson,5 C.E.,

Edinburgh, to be reported by him to the Admiralty. This produced

another letter of protest from Mr. Goldsmith on the 29th of

January. At the end he begs to be excused for his hasty and

rapidly digested remarks should they be deemed intrusive. The

"remarks" consisted principally of the advice that caution was

very necessary, and of a re-expression of his opinion that a

deputation should be sent to London. The railway company, he

says, had been there and told their tale. Why should the

trustees not do so also? The telegraph, railway, writers,

engineers, and London agents had been put in requisition against

them. Why not go and do likewise? The battle was not to the

strongest nor the race to the swiftest! "Remember," he

concludes, "the fable of the bundle of sticks. United, like you,

they were strong—disunited, easily broken and frail! "

By the 3rd of February an agreement had been

entered into between the trustees and the railway company. This

Mr. Goldsmith had perused, and on finding that it did not

exclude the right of the inhabitants to negotiate for

compensation for the loss of their beach servitude he once more

took up his pen. This time he urged the calling together of the

inhabitants. He says, " Had I seen the agreement sooner I should

have advised this course. The agreement is bad law in many

particulars." And with these words he disappears from the scene

as suddenly and mysteriously as he had entered upon it.

Amongst the other correspondence we find the

information that most of the young whales that were then caught

in the Firth near Bo'ness were cut up on the beach west from the

harbour, and thereafter carted along it to the whale-fishing

company's boil house.

XVIII

The following is a summary of a letter from the

Admiralty to the trustees, dated 18th February, which explains

the exact position of affairs. It was based upon the careful

report of Mr. Stevenson, who on behalf of the Admiralty had

inspected the ground and heard the views of parties. It may be

mentioned that on that occasion the trustees took the

opportunity of mentioning to him that the slag thrown out at

Kinneil Ironworks into the Firth had done great injury to the

beach, and insisted on his reporting this to the Admiralty:—The

railway was to be carried on an embankment from the pier of

Bo'ness harbour to the salt pond. This was a distance of 500

yards. Being generally about 100 feet seaward of high water mark

the line would clearly be interposed between the shore and the

sea. All access by the public to the shore for the purposes of

walking, bathing, and drying clothes, and also for carts as

hitherto, would thus be cut off. Beyond the site of the railway

embankment the foreshore was flat and muddy, and there were one

or more jetties there which would be cut off and rendered

useless. It would be of little benefit to the inhabitants to

have openings or archways under the railway, as immediately

outside .of the embankment the foreshore was soft mud. The slip

of land intervening between the railway and the embankment must

be filled up, as otherwise it would become filthy and a nuisance

to the town when no longer washed by the sea. Undoubtedly by the

construction of the railway the public would be deprived of some

advantages and of access to the sea heretofore enjoyed.

The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, says

the writer in conclusion, could therefore only treat this case

in the same manner as a number of others of a like character,

namely, that at the embankment, and between the railway and the

sea wall for retaining the same, there be laid out and for ever

maintained by the company a public way or walk, not less than

300 yards in length and not less than 12 feet wide; that three

level crossings, or timber footway crossings, over the railway,

not less than 6 feet high, be provided to give the public access

to the public way at specified sites; that three flights of

steps leading from the public way to the foot of the sea wall of

the embankment be provided; and that the necessary culverts or

drains across the railway be put in to keep the town dry or

clean as heretofore. The parties having landing jetties on the

line of the shore to be cut off would require to have others

erected outside of the sea face of the railway embankment by the

company, with access thereto across the railway. And, lastly,

the arch already made under the railway near the salt pond would

fall to be maintained by the railway company, along with a

proper road leading to the same—a clear headway of 7 feet to be

allowed under the arch.

This then explains the origin of the promenade,

which was shortly afterwards constructed on the lines just

indicated. It existed for a long number of years, and, being the

property of the townspeople, was well taken advantage of. The

three level crossings were not a success, as they were

frequently blocked by long trains of waggons when railway

traffic at the harbour began to develop. Several accidents—some

of them fatal— occurred, for which the railway company had to

pay compensation. The inhabitants therefore were ultimately

approached many years ago to sell their rights to the North

British Railway Company. After long negotiations it was

eventually arranged that in exchange for their rights and

privileges they receive £150 per annum for all time. This was

then believed to he an advantageous arrangement, and the annual

income gradually accumulated and came to form what was known as

the Promenade Fund or Common Good. However, in the many changes

and re-arrangements made with the railway company in subsequent

years, the annual payment seems to have become merged in

something else, and the Promenade Fund long ago exhausted in

public improvements. |

|