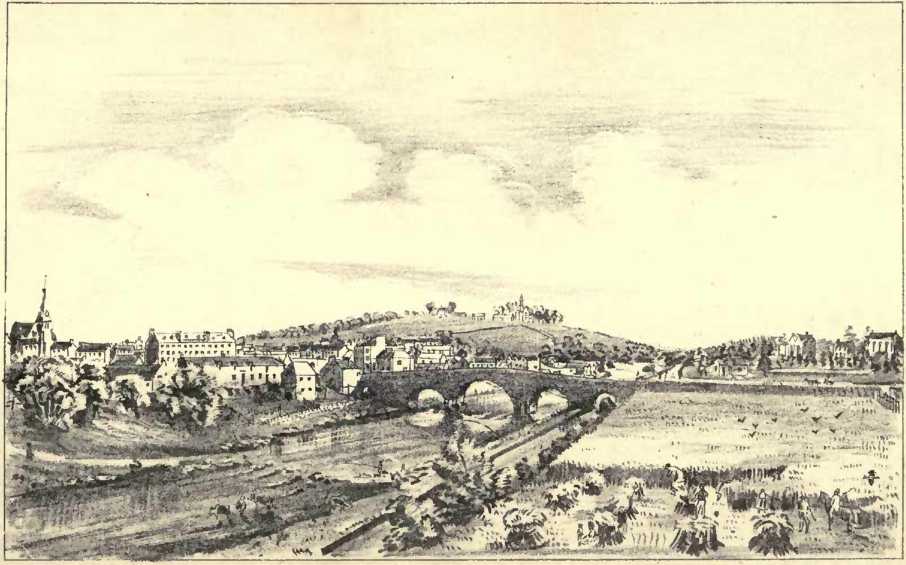

|

King Charles I.—Charter of

Burgh of Barony—Barony Court—Gallows Knowe—Montrose-Sacking of Xewton

Castle—Donald Cargill—John Erskine—The Ghost of Mause : Full

Description—Prince Charlie and the Curlers’ Dinner—Duke of Cumberland at

Woodlands—Division of the Muir of Blair—Coble Pule—Boat Brae—Muckle Mill

Erected— Purchase of Blairgowrie Estate—Military Service in Blairgowrie—

Enrolment Returns, 1803 -A Rifle Corps—A Distinguished Officer— Burgh

Charters—Erection of Parish Church—Stage Coach—Introduction of Gas and

Printing—Visits of the Queen—Auld Brig o’ Blair—An Incident of the French

Resolution—The First Newspaper —Introduction ot Railway Service—A Good

Story—Burns Centenary Celebration—Inauguration of Volunteer Movement, 1859.

DURING his first visit to

Scotland, 1633-1634, King Charles I. granted a charter, dated 9th July,

1034, in' favour of George Drummond of Blair, by which Blairgowrie was

erected into a Burgh of Barony, whereby Barons or Lairds were empowered to

hold Courts in their own districts for the trial of thieves and other

characters disgraceful to society. A Barony Court was established at

Blairgowrie, and held sittings for a considerable time. The Courthouse is

supposed to have been on the “Hirehen Hill.” where the offices of the Parish

Church Manse are now erected, the place of execution being the “Gallows

Knowe,” immediately to the west of Newton Castle. Traces of the mound might

have been observed till within a few years ago, when the ground was ploughed

up. The fields still bear the name *Gallowbank.”

King Charles, seeking to

establish the Episcopacy of Scotland, as his father James I. vainly

endeavoured to do, roused the people of the land to form together an

Association for the Protection of Religious Liberty. A ‘Solemn League and

Covenant” was entered into in 1638, and none was more enthusiastic in its

support than James Graham. Marquis of Montrose, who ultimately became its

bitterest enemy.

Montrose, for the

gratification of his own passions, as much as for the sake of the religious

liberties of the people, conceived the idea of subduing the kingdom, and

pursued for a number of years an excursive warfare against those who had so

bound themselves against Episcopacy.

Descending suddenly where

least expected, Montrose achieved many a victory, and took up residence for

some time at Dunkeld. Here he was informed that the army under Generals

Urrie and Baillie had crossed the Tay against him, but he thought it

advisable to “hie” out of the way, and on his march to Dundee sacked Newton

Castle, 1614. Urrie and Baillie, following up, encamped on the Blairgowrie

estate, passing eastwards through Forfarshire to Dundee, where Montrose had

posted himself, but the historian records that no engagement took place

between the rival armies at this time.

Newton Castle must have been

rebuilt again shortly after this, as it was once more burned down by Oliver

Cromwell.

In the year 1033 the soldiers

of Glencairn were ranging through the parish. In 1679 the famous Rattray

Covenanter, Donald Cargill, while on a visit to his parents at the Hatton of

Rattray, was pursued by dragoons, and only escaped by leaping the Keith

above Blairgowrie.

In 1726 a Blairgowrie

gentleman, John Erskine, wae an unsuccessful candidate to represent

Perthshire in Parliament.

The year 1730 was a memorable

one for Blairgowrie, the whole parish being in a commotion regarding the

extraordinary proceedings caused by Soutar, one of the tenants of Middle

Mause, declaring he had been ordered by a supernatural being to seek for

human bones in a certain place. The place was known as the “ Isle,” situated

between two or three small streams on the estate of Roehalzie, near the

south-east march adjacent to the old turnpike road from Blairgowrie to Cally

which passes up by Woodhead.

Soutar declared that the

apparition was in the form of a dog, but spoke with a human voice, declared

itself to be a David Soutar who had left the country over a century ago, and

that he (David) had killed a man at the “Isle” 33 years before, whose bones

must now be disinterred and receive burial in a churchyard, assigning as a

reason for his bestial form that he had used his dog as an instrument in the

murder.

There is a tradition that the

man was murdered for his money; that he was a Highland drover on his return

from the south ; that he had arrived late at night at the Mains of Mause and

wished to get to Rochalzie; that he stayed at the Mains of Mause all night,

and left it early next morning, when David Soutar, with his dog, accompanied

him to show him the road, and that, with the assistance of his dog, he

murdered the drover and took his money at the place mentioned; that there

was a tailor at work in his father’s house that morning when he returned

after committing the murder, and that his mother, being surprised at his

absence and appearance, asked him what he had been about, but he made no

answer; that he did not remain long in the country afterwards; that he went

to England and never returned ; that the last time he was seen he went down

the Brae of Cochrage; and that in answer to the question by William Soutar

why the apparition troubled him, the apparition said, “ Because, after I

killed the man, yours was the first face I saw in your mother’s arms.”

An old woman who died near

the end of last century used to say that “the siller of the drover paid for

the wood with which the west loft in the old Kirk of Blair ««s made,” but

she gave no explanation of her meaning.

About midnight on Wednesday,

23rd December, 1730, being in bed, “I (William Soutar) heard a voice, but

said nothing. The voice said, ‘Come away.’ Upon this I rosei out of bed,

cast on my coat, and went to the door, but did not open it, and said, ‘ In

the name of God, what do you demand of me now?’ It answered, ‘Go, take up

these bones.’ I said, ‘How shall I get these bones?’ It answered again, ‘ At

the side of a withered bush, and there are but seven or eight of them

remaining.’ I asked, 'Was there anyone in the action but you?’ It answered,

‘No. I asked again, ‘What is the reason that you trouble me more than the

rest of us? ’ It answered, ‘Because you are the youngest.’ Then I said to

it, ‘ Depart from me and give me a sign that I may know the particular

place, and give me time.’ The voice answered as if it had been at some

distance from the door, ‘You will find the bones at the side of a withered

bush; there are but eight of them, and for a sign you will iind the print of

a cross impressed upon the ground.’” On the 29th of December, William Soutar,

his brother, and seven or eight men met at the “Isle,” and on digging at a

particular spot, as indicated by the apparition, several human bones were

found, the unearthing being witnessed by the parish minister, the laird, and

other persons to the number of forty.

The bush described by the

apparition was found to be withered about half-way down, and the sign was

about a foot from the bush. The sign was one exact cross, thus X. each of

the two lines of which was about 18 inches long and 3 inches broad, and

impressed into the ground, which was not cut, for an inch or two.

The following is the “Account

by William Soutar, being extracts from the original MS. written by Bishop

Rattray, taken down at the time from William Soutar’s mouth ” :—

“In the month of December,

1728, about the skysetting, I and my servant, with several others living in

the same town, heard a shrieking, and, I following the horse with my servant

a little way from the town, we both thought we saw what at the time we

judged to be a fox, and hounded two dogs at it, but they would not pursue

it.

“About a month after that, as

I was coming from Blair alone about the same time of the night, a big dog

appeared to me, of a dark grayish colour, betwixt the Hilltown and Knowhead

of Mawes on a lie ridge a little below the road, and, in passing me, touched

me sensibly on the thigh at my haunch bone, upon which I pulled my staff

from under my arm and let a stroke at it, and I had a notion at the time

that I hitt it, and my haunch was painful all that night; however, I had no

great thought of its being anything extraordinary, but that it might have

been a mad dog wandering.

“About a year after that (to

the best of my memory), in December month, about the same time of the night

and at the same place, when I was alone, it appeared to me again just as

before, and passed by me at some distance, and then I began to have some

suspicion that it might be something more than ordinary.

“In the month of June, 1750,

as I was coming from Perth from the cloth market, a little before skysetting,

being alone at the same place, it appeared to me again and passed by me as

before. I had some suspicion of it then likewise, but I began to think that

a neighbour of mine in the Hilltown having ane ox lately dead, it might be

but a dug that had been at that carrion, by which I endeavour to put that

suspicion out of my head.

“On the last Monday of

November, 1730, as I was coming from Woodhead. a town in the ground of

Drumlochy, it appeared to me again at the same place, and after it had

passed by me. as it was near Retting out of my sight, it spoke with a low

voice, but so as I distinctly heard it, these words, “Within- eight or ten,

days, do or die,' and it having then disappeared no more passed at that

time.

“On the morrow I went to my

brother, who dwells in the Nether Aird of Drumlochy, and told him of this

last and all the former appearances, which was the first time I ever spoke

of it to anybody. He and I went that day to see a sister of ours in

Glenballow, who was a-dying, hut she was dead before we came. As we were

returning home, I desired my brother (whose name is James Soutar to go

forward with me till I should he past that place where it used to appear to

me, and just as we were come to it, at ten o’clock at night, it appeared to

me again as formerly, and, as it was passing over some ice. I pointed to it

with my finger and asked my brother if he saw it, but he said he did not nor

did his servant who was with us. It spoke nothing at the time, but just

disappeared as it crossed the ice.

“On the Saturday night

thereafter (5th December, 1730, as I was at my sheep cotes putting in my

sheep, it appeared to me again at daylight, betwixt da}' and skylight, and

upon saying these words, ‘Come to the spot of ground within half ane hour,’

it just disappeared, whereupon I came home to my own house and took up a

staff and also a sword with me, off the head of the bed, and went straight

to the place where it formerly used to appear, and after I had been there

some minutes, and had drawn a circle about me with the staff, it appeared to

me, and I spoke to it, saying, ‘What are you. that troubles me? ’ and it

answered me, 'I am David Soutar, George Soutar's brother; I killed a man

more than five-and-thirty years ago, when you were but new born, at a bush

be east the road as you gu into the isle;’ and as I was going away I stood

again and said, 'David Soutar was a man, and you appear like a dog,’

whereupon it spoke again and said, ‘I killed him with a dog, and am made to

speak out of the mouth of a dog and tell you, and you must go and burry

these bones.’

“When breaking up the ground

at the bush we found the following bones, viz. the nether jaw with all the

chaft teeth in it, one of the thigh bones, both arm bones, one of the

shoulder blades, one of the collar bones, and two small bones of the fore

arm.”

The bones were carefully

wrapt in linen and placed in a coffin made by a wright, who had been sent

for from Clayquhat, and they were deposited in a grave in the Kirkyard of

Blairgowrie the same evening.

It has generally been

supposed that this William Soutar was labouring under a delusion, or that it

was a trick played on him by one of his neighbours. As for the bones found,

they have been supposed to be the remains of a calf which had been buried

there some years before. The story is, even to this present time, believed

as true by a few credulous and superstitious beings.

The winter of 1745 was hard,

and the ice was keen, and the curlers of Blair, taking a day on the ice at

the “Lochy” (now a thing of the past), had a dinner of beef and greens

preparing for them at Eppie Clarke’s Inn, at the Hill o’ Blair, when Prince

Charlie and some of his Highlanders invaded the place, ate up everything,

and departed, refreshing themselves again and washing the dinner down at a

small well near Lornty Cottage, now known as “Charlie’s well.”

The army of the I >uke of

Cumberland, on the march to the north against the rebel forces, encamped on

the Muir of Blair, the Duke, with his officers, occupying the old house of

Woodlands, while his cavalry and ontposts were garrisoned at Newton Castle.

The Beech Hedge.

Early in the spring of 1746

the now famous Beech Hedge of Meikleour was planted.

About the year 1770 there

were large muirs—some of them many hundreds or thousands of acres in extent—

attached to many parishes both in the Highlands and Lowlands of Scotland,

and, with a general belief, with the object of promoting draining,

cultivation, and the general improvement of the country, it was highly

desirable that these muirs should be divided amongst all persons having any

interest in them, in proportiop to the extent of their respective interests.

The law of the time favoured

this view of the question by empowering the Sheriffs or the Sheriffs’-Depute

of the various counties of Scotland to make such partitions on submissions

or applications being made to them by all persons having any interest

whatever, either large or small, in any particular muir, and to apportion

and divide it accordingly.

In terms of a submission to,

and a decreet-arbitral by, John Swinton, Sheriff-Depute of Perthshire

(proceedings with reference to which were commenced in 1770 and concluded in

1774), it appears that all persons having any interest in “The Common Muir

of Blair” made application to have it divided among them in proportion to

their legal interest therein.

It was accordingly so

divided, in terms of the decreet-arbitral referred to, amongst the then

proprietors of the estates of Meikleour, Rosemount, Ardblair, the two

Well-towns, Parkhead, Carsie, and the then proprietor of Blairgowrie and his

feuars. At this time the feuars numbered eleven in all, who (together with

the minister of the parish, who got his share) represented the village of

Blair congregated around the Parish Kirk.

The block allotted to and

subdivided among them consisted of nearly fifty Scotch acres, divided into

twelve lots of different sizes in proportion to their respective rights of

each person concerned. On this block now stand the villas of Woodlands,

Heathpark, Brownsville, Shaw-field, and a number of smaller cottages.

Leaving the glebe out of the reckoning there is not one of those eleven

separate holdings now belonging to the descendants of the original feuars of

Blair—from whom, or their assignees, the present owners have acquired their

rights to purchase. The above described block was what the then feuars of

Blair got for their interests, in terms of their charters, in exchange for

their “ servitude of pasturage, fewal, foull, divot, &c., in the ‘Great

Common Muir’ of Blair recently divided.”

In accordance with the terms

of their Charters they had also similar servitudes on certain parts of the

Blairgowrie Estate proper, and, for the convenience of themselves and the

then proprietor, they jointly petitioned the Sheriff that these rights

should also be valued, and that another block (or blocks) of land should be

taken out of the Blairgowrie Estate and divided, in terms of law, amongst

those having claim. Accordingly, 011 the 21st January, 1777, another

submission was made and a decreet-arbitral was issued thereon by John

Swinbon, Sheriff-Depute of Perthshire.

It is described as being

between Thomas Graham, Esq. of Balgowan (then the Superior), and William

Raitt, feuar, Hill of Blair, and others, “the vassals of the town of

Blairgowrie below the Hill.”

To William Raitt and another

were allotted eight acres on the Lornty Road, and to the vassals below the

Hill “fourty acres” on the Perth Road, divided into different lots, as in

the case of the feuar’s share of the “Common Muir.”

Before 1777 there was no

bridge over the river at Blairgowrie, all vehicular traffic having to cross

by a ford where the “weir” is now erected, access being had from Lower Mill

Street, down by where Mr Pell’s slaughter-house is, while foot-passengers

were taken across in a small coble or boat, which ceased to ply when the

bridge was built. The part of the river where the boat crossed was known as

the “ Coble Pule,” and the ascent on the Rattray side as the “Boat Brae,”

which name it retains to this day.

The year 1778 saw the “Muckle

Mill” erected, in which tlax was first spun here by machinery.

On the 20th September, 1788,

the estate of Blairgowrie was purchased by a predecessor of the present

proprietor, Col. Allan MacPherson (17—1817), from Thomas Graham, Esq. of

Newton and Balgowan, the purchase, of course, including Graham’s share of

the “Common Muir ” of Blair, in terms of the decreet-arbitral of 1774,

situated immediately to the east of the fejiars’ share of the same.

At the time of the threatened

invasion of Britain by Napoleon in 1804, service in the British Army was

compulsory, and those drawn for it could only obtain exemption on paying

either a penalty or finding a substitute. In the following list of the

“Military Service in Blairgowrie, 1803,” the first name in each couple is

that of the principal, where a second name is given it is that of the

substitute, whose age is stated :—

“Subdivision of the

Blairgowrie District in the County of Perth.

“Return of Enrolment, dated

the eleventh and twenty-eighth days of February, eighteen hundred and three

years.”

James Dufftis, merchant,

Blairgowrie.

William Blair, shoemaker, do. (39).

James Duncan, weaver, do.

Henry Henderson, weaver, do. (22).

John Fleeming, weaver, do.

James Dowuie, weaver, do. (24).

John Donaldson, weaver, East Banchory.

George Robertson, weaver, Dundee (24).

William Isles, weaver, Weltown.

David Yeaman, weaver, Rattray (18).

Robert Straiton, weaver, Blairgowrie.

Thomas Bog, weaver, do. (36).

John Playfair, saddler, Blairgowrie, was found unfit, and there was balloted

in his room Duncan Keay, weaver, Blairgowrie, who paid the penalty of £10.

William Cowan, wright, Blairgowrie, paid penalty of £10.

Patrick M'Pherson, surgeon, Blairgowrie, did not appear.

In 1801, a corps of

Volunteers was raised in the town to assist, if required, the regular army

against invasion.

The corps comprised 8

officers, 65 privates, and 1 drummer.

One of the officers of this

corps (2nd Lieut. James Dick) rather distinguished himself one morning by

showing his readiness for action. It happened during a wet and stormy night

that the meal mill took fire, and the flames rapidly spreading threatened to

destroy the whole building.

In order to alarm the

inhabitants and obtain assistance, the Volunteer drum was beaten through the

streets. The rattle of the drum and the confused noise suddenly awoke the

Lieutenant from his sleep, and, hastily getting out of bed, he seized his

sword, rushed out into the street in his trousers and, shirt, and,

flourishing his sword to the passers-by, exclaimed, “Where are they landed,

boys! Where are they landed?” the gallant officer being under the delusion

that the Freuch had really crossed the Channel.

Early in the beginning of

this century (18—) the Superior of the town, “ by reason of the great

increase of the town, judged it necessary to put the police and government

thereof under proper regulations, and for this purpose selected and made

choice, from among the most respectable inhabitants, of a Bailie and four

Councillors, with a Treasurer, Clerk, and other officers of Court, by way of

trial, for the management of the funds and common good of the Burgh,

administration of justice, and maintenance of peace and good order.”

This system was further

extended in 1809, when Colonel MacPherson granted a charter conferring

certain privileges on the burgesses holding feus or building-stances in the

village under him as Superior, and empowering the Bailie, who should be

elected in terms of that charter, to hold Baron Courts for the trial of

offences not exceeding £2 in value, and petty criminal offences. This

charter held good until further extensions were made in 1829, and again in

1873.

Under the Charter of 1809,

James Scott was elected the first Bailie of the town in 1810.

In 1824 the present Parish

Church on the Hill of Blair wais erected on the site of the old “mercait

gate,” the foundation stone being laid with great ceremony by William

MacPherson, Esq. of Blairgowrie.

For a number of years,

beginning in 1831, a stage coach, named “Baron Clerk Rattray,” ran twice

a-week between Blairgowrie and Coupar Angus.

In 1833 the householders

resident in the Burgh adopted part of the Police Act III. and IV., William

IV., cap. 46, by which certain powers were vested in the Chief Magistrate

and four Commissioners for the management and regulation of the Police

Department of the town, and the jurisdiction of the Chief Magistrate in

criminal matters was enlarged.

The town in 1834 was first

lit up with gas, when the present gas works were erected, and 1838 marked

another epoch when the first printing press was introduced.

The temperature, in common

with all districts bordering on the Highlands, is subject to frequent and

sudden variations. On the 23rd October, 1839, a most severe shock of

earthquake was felt throughout the district about 10 p.m., and was

accompanied by a noise resembling distant thunder, or the rapid passage of a

heavily-loaded vehicle over a newly-metalled road. The motion at the

commencement of the concussion was of a waving or undulating nature, and,

terminating in a vibration or tremor, becoming gradually less distinct until

it ceased altogether.

In 1842 Blairgowrie was first

honoured by a visit from royalty in the person of Her Majesty Queen Victoria

on her way to Balmoral. On her progress through the estate of Glenericlit,

then possessed by General Chalmers, a Peninsular hero, she conferred on him

the hem out of Knighthood (Sir William Chalmers of Glenericlit).

During the great spate of

October, 1847, one of the arches of the “Auld Brig o’ Blair” gave way, but

was speedily and substantially repaired.

About the time of the

outbreaking of the French Revolution in 1848, the village of Blairgowrie,

obscure and insignificant as it then was, shared in the general excitement

of the nation. At the time that the Militia Act first came into operation

the class of persons who were liable under its enactments, and the lower

ranks in general throughout the country, were greatly discontented with the

measure, and on the day when the Justices of the Peace for the district met

in Blairgowrie for the purpose of balloting for those who should serve, this

discontentment broke out into open violence. Great crowds from this and all

other parishes collected in the district, made prisoners of Colonel

MacPherson of Blairgowrie, Sir William Ramsay of Bamff, and other gentlemen

assembled, and confined them in the Inn until they got hold of the only

writer in the village, whom they compelled to draw out a bond, to be

executed by the Justices, by which they should be bound to abstain in future

from any measures for enforcing the obnoxious Act. This document was

subscribed by the captives under the threats of the mob. Satisfied with

this, in the belief that they had effectually extinguished the Militia Act,

they allowed their prisoners to go free, and themselves dispersed peacefully

to their respective homes. But a week had not passed over their heads when a

body of the Sutherland Fencibles made their appearance and seized on the

most active rioters. This vigorous proceeding quelled the disturbance, and

the provisions of the Act were thenceforward carried into effect without

further trouble.

On the 28th of April, 1855,

the first number of a local newspaper was issued by Messrs Ross & Son from a

very small office in the High Street. The paper bore the title: —“Ross's

Compendium of the Week’s News, to be issued occasionally,” and consisted of

a single sheet, 12|- inches long and inches wide, printed on both sides.

Occasionally the wreek’s news was so scant that one side was sufficient both

for news and advertisements.

On the 28th July of the same

year another epoch in the history of the town was the opening of the

Blairgowrie branch of the Scottish Midland Junction Railway. Up to this time

all cartage of goods had to be done from the neighbouring town of Coupar

Angus or from Perth and Dundee. For passenger traffic the first train

started at 8 a.m., consisting of two first class, one second class, and two

third class cars. There was a rush to secure tickets long before the hour of

starting, and the train was well filled.

There had been a pretty

general impression that the line would be inaugurated by several excursion

trains, gratis, but, as hope turned to disappointment, “no demonstration was

made, no flags were waving, no shouts were heard, and no wish was expressed

that the Blairgowrie branch railway would flourish.”

A good story is told

regarding the railway on its first introduction to the town. One day a party

of clergy had been in town from Dundee attending a Presbytery meeting,

dressed in black, with “white chokers.” They arrived at the Station just

before the 4.30 p.m. train should start, for the purpose of taking their

places to return to Dundee. Suddenly, one of them recollected he had

forgotten something, and the others promising to wait for him, he started to

get the forgotten article. Train time was up, and the Station officials

tried to get those who remained into the carriages, but they woidd not stir

until their friend had returned. In vain they were told the train would

start without them. They knew better; the train would not go off and leave a

dozen well-dressed individuals standing on the platform. The guard’s

patience being exhausted the train did start. Just as it was leaving the

platform, the individual appeared running down the bank at the foot of Rorry

(Reform) Street, and, seeing the train on its way, took a slanting direction

across the fields as if to intercept it. On seeing this, the whole party

jumped upou the line and started in pursuit. The railway officials and the

guard had some amusement watching them, but the pursuit of the “iron horse”

was fruitless, the whole party losing the train.

Once again, on 29th August,

1857, did Her Majesty Queen Victoria and suite honour Blairgowrie by passing

through it en route to Balmoral. The Royal train arrived at Blairgowrie

Station at half-past twelve. A company of soldiers, partly of the 1st and

partly of the 21st Royals, many of them decorated with medals, were in

waiting at the terminus, and presented arms on Her Majesty’s armyl.

On alighting from the

carriage, Her Majesty was received by Captain Campbell and Lady of Achalader

and a numerous party of the principal farmers. After receiving a beautiful

bouquet from Captain Campbell’s six-year-old son, Her Majesty retired to the

waiting-room, which was beautifully fitted up under the direction of Mrs

Campbell. After a stay of a little over five minutes, during which she

partook of biscuits and fruit, the Queen entered her travelling carriage and

drove off at an easy pace for her Highland Home. The road from the Station

to New Rattray was lined with a crowd of spectators, who welcomed Her

Majesty and Consort with enthusiastic cheers, which were gracefully

acknowledged. Along the route, more especially at Glenericht, floral arches

and banners were very abundant. The Royal party partook of lunch at Spittal

of Glenshee, and reached Balmoral at six o’clock.

* * * * * *

The morning of Tuesday, 25th

January, 1859—“a red-letter day” in the history of Scotland—dawned bright

and beautiful in Blairgowrie. .This day, long looked forward to by Scotsmen

in all parts of the world, had come round, and Blairgowrie prepared to

celebrate the centenary of the birth of Scotland’s own Poet in its own way.

In celebration of the

centenary of the birth of Burns, a party of 40 gentlemen, belonging to the

town and district, met in - the hall of MacLaren’s (Royal) Hotel, about 4

p.m. The hall was decorated with evergreens, arranged upon the walls in

various tasteful figures. The instrumental band, under "Willie' Scrimgeour,

was in attendance for some time, and the music added greatly to the effect

and enjoyment of the meeting. Mr Alexander Robertson, banker, presided, and,

after a sumptuous supper, gave the toast of the evening, “The Memory of

Robert Burns, Scotland’s Immortal Bard,” which was drunk to in solemn

silence. A most enjoyable night was spent, enlivened with song and

sentiment.

A demonstration was also held

iu the Malt Barns at “The Hill,” which was perhaps the most successful

meeting ever held in Blairgowrie up to this time. Between four and five

hundred persons were present, from the youth of tender years to the sire of

grey hairs, drawn from all ranks of society. Mr Allan Macpherson occupied

the chair, and spirited addresses were given by the Chairman, Messrs Thomas

Mitchell of Greenfield, William Davie of Millbank, John Bridie, and Thomas

Steven, while a glee party and the Westfields Flute Band delighted the

audience with music, the whole concluding with the singing of “There was a

Lad was born in Kyle.”

The year 1859 also saw the

inauguation of the Volunteer movement; and the first meeting for the

formation of a Rifle Corps in Blairgowrie was held 13th December, 1859. They

were embodied under duly approved officers, 16th March, 1860. The corps was

present in Edinburgh on the 7th August, 1860, at the review of the Scottish

Volunteers by Her Majesty the Queen.

BLAIRGOWRIE 1860 |