|

DURING the 350 years occupied

by the Romans in attempting to conquer Scotland, a revolution took place in

the religious opinions of the people. The Druidical system, although

embracing such truths as that there is only one God, that the soul is

immortal, that men will be punished or rewarded in a future state according

to the actions which they have performed on earth, etc., yet, consisting as

it principally did of frivolous and debasing rites, particularly that of

offering human sacrifices, it could not stand before the power and progress

of divine knowledge. The individual or individuals who first introduced the

light of Christianity into the British Isles, are not certainly known. The

likelihood is, that during some of the rigorous persecutions carried on by

the Roman emperors against the early Christians, which was the means of

dispersing them over all parts of the known world, some of the converts

found their way to Britain, and there promulgated the faith which they had

embraced, and on account of which they had been called to suffer. The new

faith, by whatever person it was introduced, appears to have made rapid

progress in the minds of the people; and it is generally asserted that, in

the year 203, Donald, King of the Scots, with his queen and many of his

nobles, publicly embraced it, and were baptized. Then, from time to time,

arose certain illustrious divines, whom our ecclesiastical historians have

delighted to present in bright colours to the notice of their readers—such

as St Ninian, St Columba, St Kentigem, etc. St Kentigem, or St Mungo, who

flourished in the sixth century, after labouring with great zeal and success

in Wales, settled at last in the Vale of Clyde, founded a stately church at

Glasgow, and exercised a fatherly charge over the clergy in the adjacent

districts. We may conclude that a fabric for the exercise of the Christian

system had, by this time, been erected at Biggar, and that it was honoured

with occasional visits from the Clydesdale saint. It is not, however, for

fully 500 years after the time of St Mungo, that we have any authentic

reference to the Church of Biggar. The earliest allusions to it, or rather

to its clergymen, are to be found in the chartularies of the religious

houses.

The Church was a rectory in

the deanery of Lanark, and was dedicated to St Nicholas. Robert, the parson

of Biggar, is mentioned as a witness of a grant by Walter Fitzallan to the

monks of Paisley,

between 1164 and 1177. The

name of Master Symon, the physician of Biggar, and also, as has been

conjectured, the parson of the church, is given as a witness to a charter by

Walter, Bishop of Glasgow, between the years 1208 and 1232. About the year

1290, Philip de Keith, son of William de Keith, Knight Marischall, was

Rector of Biggar. In 1329 Sir Henry, Rector of Biggar, was one of the royal

chaplains, and clerk of livery to the household of the king. Walter, Rector

of Biggar, is mentioned in a charter of Malcolm Fleming, Earl of Wigton,

during the reign of David II. After this, very little is known regarding

Biggar Church and its incumbents for a period of two centuries.

In Baiamund’s or Bagimont’s

Roll, which, in the state in which it now exists, may be held to represent

the value of ecclesiastical livings in the reign of James V., the rectory of

Biggar is valued at L.66,13s. 4d., and in the Taxatio Ecclesiae Scotians at

L.58. By an indenture of assythment, and afterwards by a decreet arbitral in

the reign of James V., it received an additional endowment of L.10 yearly

from Tweedie of Drummelzier, ‘ to infeft ane chaplaine perpetualie to say

mass in ye kirk of biggair, at ye hye altar of ye sayme,’ for the soul of

John Lord Fleming, whom Tweedie had murdered.

It is supposed that it was

this endowment or mortification that first suggested to Malcolm Lord Fleming

the propriety of founding a collegiate church at Biggar, and conferring on

it a number of new endowments. He appears to have been a devoted Roman

Catholic. He had identified himself with the party who, at the time, were

striving, by every means in their power, to uphold the tottering fabric of

the Romish Church, and he was, no doubt, anxious to give a notable

manifestation of his zeal in the cause which they had so much at heart. The

principles of the Reformation, first enunciated in Germany by Martin Luther

in 1517, had now spread over all Europe, and were even making rapid progress

in the comparatively obscure realm of Scotland, and alarming the fears of

the devotees of the Romish superstition. Patrick Hamilton and George Wishart

had proclaimed these principles with impressive effect, and had testified

their sincerity by laying down their lives; and Sir David Lindsay of the

Mount, and George Buchanan, had written and published most pungent satires

on the pernicious doctrines and ungodly lives of the Romish priesthood A

corresponding desire was consequently manifested by the party, with whom

Fleming was connected, to prop up the superstructure of Romanism, which had

been so vigorously and successfully assailed.

The first intimation that we

have of Lord Fleming’s intention to build a collegiate church at Biggar, is

contained in a writ still preserved in the archives of the Fleming family.

It is from Gavin, Commendator of the Benedictine Monastery of Kelso, and

bears date the 26th November 1540. It states that he had heard of Lord

Fleming’s design to found and endow a college church at Biggar; that the

right of patronage of the Church of Thankerton had been obtained by the

Abbots of Kelso from his lordship’s predecessors; that in these evil times,

by the increase of Lutheranism, all true Catholics were bound to contribute

to so good a work; and that he was most anxious that his lordship should not

be diverted from his resolution, or suffer prejudice by the Abbots of Kelso

continuing to hold the patronage of the Church of Thankerton. On these

grounds, with consent of David Hamilton, then rector of the said church, he

transferred to Lord Fleming, in name of the college to be founded and built,

the right of patronage of that church, with its whole rents and emoluments,

to be bestowed on one or more prebendaries of the foresaid college. The only

reservation which he made, was that the Church of Thankerton should always

be provided with a vicar pensioner, who should discharge the clerical duties

of the charge, and have for his sustentation twenty merks Scots out of the

first and readiest of the teinds of the parish, with a house, garden, and

four acres of land This writ was confirmed by the Archbishop of Glasgow, at

Edinburgh, 1st May 1542.

The new church was founded in

1545, and erected on the site of the old building dedicated to St Nicholas.

The parson of the old church at the time was Thomas Chappell, who, on the

presentation of Malcolm Lord Fleming, was collated to his office by the

Archbishop of Glasgow, on the 17th April 1542. It has been supposed by some

persons, and among others by Grose, who took a sketch of the Church from a

window of the manse in 1789, and published an engraving of it in his work on

the ‘ Antiquities of Scotland,1 that the present edifice is much older than

the date above mentioned This, to some extent at least, is certainly a

mistake. From statements in the founder's testament, executed in 1547, and

also in a charter of the Abbot and Chapter of Holyrood connected with this

Church, and dated a few years afterwards, it is evident that the erection

had been commenced and carried on, to some extent, by the founder, Malcolm

Lord Fleming, but was evidently left unfinished at his death, in 1547. His

son and successor, James Lord Fleming, belonged to the same religious and

political party as his father, and was, no doubt, influenced by the same

views and feelings in respect to the new collegiate Church. He is understood

to have carried on the building, and to have left it in nearly the same

state in which it exists at present.

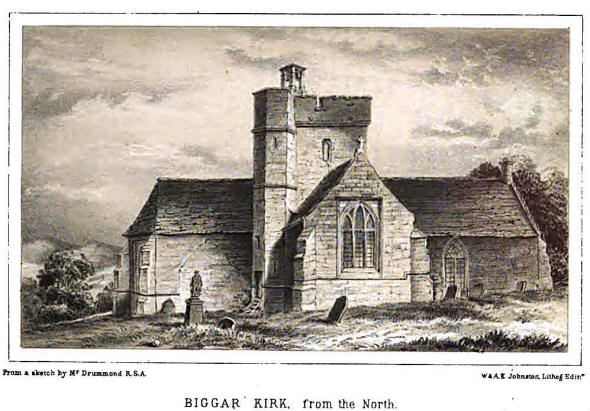

The style of the architecture

of the Church is Gothic, and the form of it is that of a cross. It was, no

doubt, intended to be all composed of ashlar work. The choir, transepts, and

tower have accordingly been built of dressed sandstone, brought evidently

from a quarry in the parish of Libberton, near Camwath ; but the nave is

constructed of rubble work, the stones employed being the rough whin which

abounds in the neighbourhood This may be a portion of the old Parish Church

made to harmonize with the original plan, or it may be a part of the

building executed in this manner by James Lord Fleming, with the view of

lessening the expense. It is said that the original plan embraced a spire,

which would have been a great ornament to the town, and a fine feature in

the landscape; but it was not built, and hence the unfinished state of the

Church is very commonly cited in the locality as an illustration of the

aphorism, ‘ Many a thing is begun that is never ended,1 like Biggar Kirk.

The walls of the tower from which the spire was to have sprung, have been

formed into a parapet with embrasures and loopholes, as if it was intended

to be a place of defence,—a use to which the towers and spires of churches

in Scotland were, in former times, not unfrequently put After all, however,

it may be questioned if it was ever intended to carry the tower higher than

it is at present It is certainly the fact, that central towers in Gothic

buildings very frequently terminate, not with a spire, but with a parapet

containing loopholes and embrasures similar to those of Biggar Kirk.

The building on the outside

is plain, presenting little more than the buttresses and mouldings peculiar

to Gothic architecture. It had two principal entrances, one in the south

transept, and the other in the western gable. The doorway in the west is

extremely plain, and is now built up; and the one on the south is composed

of an arch finely moulded. The corbels from which the mouldings spring, are

much defaced; but enough of them remains to show that they have been

ornamented with fine tracery work, and that the pattern of the one is

different from the other. On the handle or latch of the strong wooden door,

studded with nails, is the date 1697, referring most likely to the time at

which the door was made, and placed in its present position. On the left

side of this door are the remains of the ancient jougs, by which adult

offenders were fastened to the wall, and forced to remain a space of time

proportioned to their misdemeanors. On the right, at a lower elevation, are

staples, batted into the wall with lead, which were evidently intended to

suspend a pair of jougs for the confinement and punishment of juvenile

offenders. An excellent representation of this door and the chain of the

jougs is to be seen in the vignette to this volume. The buttresses on each

side of the gable of the south transept have been surmounted by carved

pinnacles; but these have long since disappeared, as well as the apex or

finial of the gable, which most likely was an emblem of the cross. The

remains of the cross on the apex of the north transept can still be very

distinctly observed On the lowest corbie, or, as they are here generally

denominated, crowsteps, of the western gable, is a carved shield of the

Fleming arms, with this peculiarity, that the cinquefoils, adopted from the

arms of the Frasers, are in the first and fourth quarters, instead of the

second and third, as they are usually found in the escutcheon of the Earls

of Wigton.

A large portion of the hewn

stones used in the building has the mark of the masons by whom they were

prepared. The practice of marking stones is known to have been observed by

masons for several thousand years. The design of it was to distinguish the

stones wrought by each workman, so that the merit or demerit of the

workmanship could at once be attributed to the proper individual It is not

uncommon to find two marks on one stone,—the one being the mark of the

hewer, and the other of the overseer, who, after inspecting the stone, and

finding it correctly wrought, put upon it the official stamp of his approval

The apprentices had generally what is called a blind mark, that is, one with

an even number of points or corners; while the journeymen or fellow-crafts

had one with an odd number, which might range from three points to eleven.

In the ancient lodges of Freemasons, a ceremony was observed at the time of

conferring a mark on a newly entered brother; and when this was over, his

name and mark were inserted in a book. We accordingly find that this was one

of the regulations adopted at a meeting of the masters of lodges, convened

at Edinburgh, 28th December 1598, by William Schaw, ‘Maister of Wark' to his

Majesty James VI., and General Warden of the Mason Graft in Scotland All the

old operative lodges, therefore, practised mark-masonry, and some of

them—and among others, the Lodge of Biggar Free Operatives—retain an

interesting roll of the marks which their members adopted and used. The

individuals who built Biggar Kirk were evidently mark-masons, and hence the

frequent marks to be found on the stones of which a portion of it is

constructed.

Two small buildings were at

one time attached to the Church, the one on the north side of the choir or

chancel, and the other on the south side of the nave. The one on the north

side, the traces of which are still to be seen on the wall of the Church, as

shown in the engraving of the Kirk, was the chapter-house, which in such

buildings was rarely to be found west of the transept. It was used for the

meetings of the provost and prebendaries, and most likely also as a mortuary

chapel The building on the south was originally, in all likelihood, the

vestry, in which the sacred utensils and vestments were kept; and perhaps it

also served the purposes of an eleemosynary, or almonry, in which alms were

distributed to the needy poor. It was in the end—and, indeed, in the memory

of some persons still living— used as a porch, and had seats all round the

walls. These buildings were removed about sixty years ago; but for what

reason, it is impossible, perhaps, now to say. Two buttresses on the iforth

side of the nave, and an arched gateway that stood at the entrance to the

churchyard, have also, in the course of time, been demolished.

The interior of the Church

was fitted up with considerable elegance. It had four altars. The high altar

and the altar of the crucifix stood in the choir or chancel, and the altars

of the two aisles were placed one in the south transept and the other in the

north transept, the two transepts being, in former times, very commonly

called * The Cross Aisles.* A screen divided the choir from the nave, and at

the eastern extremity of the choir, which was finely lighted with three

large windows, was the presbytery, into which no person was allowed to enter

except the priests. A stone on the north side of the choir had a carved

representation of a serpent,—an emblem which has a strange but emphatic

significance in the rites both of Paganism and Christianity. In the nave

were placed the pulpit, and the font for holding the holy water. The corbels

from which the groinings and arches of the roof sprung, were highly

ornamented with representations of doves, foliage, human heads, etc. These

are now much mutilated; but the heads on each side of the' eastern

termination of the nave are nearly entire, and are most likely intended to

represent the founder and his wife. In the north transept was the

organ-loft, the door to which still exists in the staircase which admits to

the tower. The ceiling, at least of the chancel, was originally of oak,

richly carved and gilt; but was removed a number of years ago, and one of

lath and plaster substituted in its place. In the tower is an apartment

which appears never to have been completed It is of square form, and has a

small window on each side ; but as these are filled with stone slabs, it is

quite dark, and can only be examined by the aid of a candle. The walls are

unplastered, and the floor and ceiling, if they ever existed, have

disappeared The oak joists, both above and below, are in a state of good

preservation. A very singular-looking shaft rests on a joist below, turns on

a pivot, and communicates with one of the joists above; while a second

shaft, with a hole in it near its, lower termination, is suspended from one

of the upper joists. It would perhaps not be easy to discover the purpose to

which this curious apparatus was applied The apartment has a spacious

fire-place, which seems to indicate that it was intended to be occasionally

occupied; but no reliable account can now be got of the use which it was

designed to serve. The tradition regarding it is, that it was the place to

which the Fleming family retired, or intended to retire, before and after

attending religious service in the Church, to assume and lay aside what was

called their ‘chapel graith.’ It is certain that the family had articles of

this kind, as is shown by the following bequests. The founder of the Church,

in his testament, says, ‘ I leif to James, my eldest son and air,* 4 the

chapell graith of siluer; that is to say, ane cross with the crucifix, twa

siluer span-dellers, twa siluer croadds, ane haly water fatt, with the haly

water stick, ane siluer bell, ane chalice with the patine of siluer, with

all the haill stand of vestments pertaining to the samen.’ James Lord

Fleming, in the testament which he executed at Dieppe in 1558, bequeathed

his ‘chapel graith* to his brother John. It consisted of the following

items:—*Ane silvere challice wfc ane pax, ane cryce of silvere, ane

eucharest of silvere, ane haly waiter fate, w* ane styk of silvere,

and ij crouats of silvere/ From these extracts it is

evident that the Flemings had not only a set of sacred vessels, but a

peculiar suit of garments, which they used while attending or performing the

rites of the Romish Church.

The

circular staircase already referred to was entered from the inside by a door

in the north-west angle of the chancel, and, besides admitting to the

organ-loft and the square apartment in the tower, communicated also with the

floor of the parapet or bartisan; and as this is covered with lead, being

open to the weather, it is usually called the Lead Loft. The door in the

inside of the Church was some years ago built up, and one in place of it cut

out of the staircase, as shown in the engraving. On the north-west side of

the interior of the staircase are the initials W.M., and on the south-east

side the initials I.H., and the date 1542. With regard to the initials

nothing can be said; and the date is certainly puzzling, as it is three

years prior to the time at which the present Church was founded. The stone

on which it is cut may have belonged to the old Parish Church, or some

person, at a period subsequent to the erection of the present Church, may

have cut it in a mere spirit of wantonness, or with a design to mislead We

put no confidence in it as calculated to establish the supposition of Grose

and others, that the whole of the Church is older than the year 1545, the

date of its foundation as a collegiate charge. The belfry was furnished with

a bell of a remarkably clear tone, which was heard for many miles round, and

was rung by a rope in the inside of the Church. This fine bell, which was

supposed to be as old as the Church itself, was unfortunately cracked by a

sexton, when tolling it at the funeral of one of the proprietors of the

parish, about forty years ago. The present bell is one of much inferior

quality, and is rung from the outside of the Church.

In the

inside of the Church a relic, now very rarely to be met with, is stiU

preserved. This is the cutty stool, on which the violators of ecclesiastical

discipline were wont, in the face of the congregation, to

make expiation for their offences. The punishment of the

cutty stool is referred to by Ferguson the poet as forming part of the

gossip around the farmer’s ingle:—

'And there how

Marion for a bastart son

Upo’ the cutty stool was forced to ride,

The waefu’ scald o’ our Mess John to bide.'

The cutty

stool of Biggar Kirk has the date 1694, with the

initndu

B. K., and is represented in the accompanying engraving.

Another

relic preserved in the Kirk is a jug. It is apparently composed of pewter,

and very much resembles a small claret-jug. It is usually denominated a holy

water fatt or jug, as, according to tradition, it was used by the Roman

Catholic priests in holding holy water. After the establishment of the rites

of Presbyterianism, the jug was used in conveying to the Church the water

used in baptism. As an old relic connected with the Kirk, we give the

annexed engraving of it. Another

relic preserved in the Kirk is a jug. It is apparently composed of pewter,

and very much resembles a small claret-jug. It is usually denominated a holy

water fatt or jug, as, according to tradition, it was used by the Roman

Catholic priests in holding holy water. After the establishment of the rites

of Presbyterianism, the jug was used in conveying to the Church the water

used in baptism. As an old relic connected with the Kirk, we give the

annexed engraving of it.

The Kirk,

although it has undergone many barbarous mutilations from the violence of

man, and suffered many injuries from the corroding hand of time, is still in

a state of good preservation, and holds out the promise of serving as the

Parish Church for ages to come.

A

proposal has lately been made to renovate the interior of the building, and

thus place it in a state similar, in some respects, to that in which it was

in former ages, and more in keeping with the altered spirit of the times.

This is to consist principally in filling the windows with stained glass; in

taking down the present ceiling of lath and plaster, and substituting one of

wood, with the groinings, pendants, and carvings, as near to the original as

can now be ascertained; and in cutting away the oak joists in the oentre

tower, and forming the lead loft into a glass cupola, in order to shed a

flood of light on the area of the Church. This proposal, with exception of

the last alteration, appears to be highly worthy of commendation; and it is

to be hoped that the present pastor of the parish, the Rev. J. Christison,

who seldom fails in any undertaking in which he embarks, will take it up,

and prosecute it to a successful termination.

Having

given a description of the building, we may now refer to the Charter of

Foundation. It is still preserved in the archives of the Fleming family,

and, with its ancient style of penmanship, and its large seals, has a most

venerable appearance. It is written in Latin, and is of great length. As a

full translation of it would occupy too much space, we will give the

substance of its most important points.

It is

addressed by Malcolm Lord Fleming to Cardinal Beaton of St Andrews. After

enumerating all that reverend father’s high-sounding titles, it goes on to

say that his Lordship, influenced by examples of piety and devotion, and

constantly desirous to increase the means of religious worship, and to press

forward more warmly and earnestly in the practice of pious deeds, so far as

justice and reason might warrant him, had been induced to found, endow, and

effectually erect a College or Collegiate Church at Biggar, with the

collegiate honour, dignity, and pre-eminence. The funds for this purpose

were to be drawn from the parish churches, benefices, chaplain-ries,

clerical revenues, and charities belonging to him by hereditary right, and

from other property bestowed on him by the favour of Almighty God He had

erected and endowed this Church to the praise, glory, and honour of the most

high and undivided Trinity; of the most blessed and immaculate Virgin Mary,

under the title and invocation of her assumption; of the blessed St

Nicholas, patron of the Parish Church of Biggar; of St Ninian the Confessor,

and all the saints of the heavenly choir. The object of the founder was the

safety of the soul of James V., late King of Scotland, of most worshiped

memory; the safety of his own soul; of the soul of his wife, Joan Stewart,

sister of the late renowned King; of the souls of his parents, benefactors,

Mends, and relatives, predecessors and successors; and of all the faithful

dead, especially those from whom he had taken goods unjustly, or to whom he

had occasioned loss or injury, and. had not compensated by prayers or

benefits. He had done all this with consent of the most reverend father in

Christ, Gavin, by the grace of God Archbishop of Glasgow, and of the wise

and venerable men, the deacons and canons of the Metropolitan Church of

Glasgow, in chapter assembled The foundation was to support a provost, eight

canons or prebendaries, four boys, and six poor men. The firm conviction of

the founder was, that in the solemnities of the mass the Son offered himself

to the Father Omnipotent, a rich sacrifice for a sweet-smelling savour; and

that to Him nothing more acceptable, gracious, and worthy could be

presented. His sincere belief in the Catholic faith also convinced him that

the mass had power to restore frail human nature, often falling into sin, to

the Father’s favour, to rescue the souls of the faithful from the pains of

purgatory, and bring them to the full enjoyment of happiness and glory. He

wished to have an assurance that he would not be found among the number of

those of whom it was said in the beginning, ‘They are a nation void of

counsel, neither is there any understanding in them. O that they were wise,

that they understood this, that they would consider their latter end! ’ And

he had pondered in his mind what is written in the Apocalypse,

'And I heard a voice from

heaven saying, Write, Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from

henceforth: Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labours;

and their works do follow them.* The founder’s charity, piety, and desire

for extending the means of religious worship, having been thus evoked, he

had, out of his hereditary patronages and acquired property, endowed the

Collegiate Church of Biggar, for the provost, canons,

boys, and poor men, as already stated, and reserved only to himself, his

wife, and his heirs, the disposition, presentation, and endowment of these

officials, as often as the office of any one of them became vacant. The

collation of the provost was to belong to the Archbishop of Glasgow, and the

admission or installation of the prebendaries and boys was to be the daty of

the provost, or, in his absence, the President of the College for the time

being.

The

provost was to be called the Provost of the Collegiate Church of the Most

Blessed and Immaculate Virgin Mary, of Biggar. He was to celebrate the

Assumption of the Virgin, in the Church of Biggar, as the principal

festival; and he was to have for his sustentation, all and whole the

produce, rents, revenues, tithes, and emoluments of the rectory and vicarage

of the parish of Thankerton, in the diocese of Glasgow, along with its

tributes and offerings, and its manse and glebe. He was, however, to pay L.10

Scots to a curate, who was to undertake the cure of souls in the parish of

Thankerton, and to bestow on him two acres of land, near the Church, for a

manse and garden. The said curate was constantly to reside in the parish,

and discharge all the duties of his office in person. The provost was also

to bear all burdens, and meet all liabilities, ordinary and extraordinary,

that, in times past, attached to the Church of Thankerton.

The first

prebendary was to be called Canon of the Hospital of St Leonards, and was to

be master and teacher of the School of Song. He was to instruct the boys of

the College, and others, who might attend, in plain song, invocation or

pricksong, and discant. He was also to be well skilled in playing the organ

for the performance of divine service. He was to receive for his support,

throughout the year, the produce of the church lands of SpittaL The second

prebendary, who was to be instructor of the Grammar School, was to be

sufficiently acquainted with letters and grammar, and was to have, for his

yearly sustentation, the lands of Auchynreoch. The third prebendary, who was

to be sacristan of the College, was to have for his annual support the

chapel founded on the lands of Gamegabir and Auchyndavy, and dedicated to

the Virgin Mary, with its pertinents; and six merks of annual rent in

Kirkintulloch, along with two acres of land, for a manse and garden,

belonging to the chapel, and at that time in possession of Andrew Fleming of

Kirkintulloch. The duty of this prebend was to ring the bells, to light the

wax tapers and tallow candles on the high altar, the altars of the two

aisles, and the altar of the crucifix. For the maintenance of the tapers and

candles during winter, he was annually to receive L.5 Scots, drawn from the

produce and emoluments of the priest’s office in the Church of Biggar. This

prebend was also to prepare the vestments and ornaments of the four altars;

he was to wash, dean, and repair, as often as necessary, the cups,

vestments, and ornaments; and when this was done, he was to cover them up in

their respective places on the altars. For this service, he was to receive

the annual sum of L.5 Scots, levied from the priest’s office of the Church

of Biggar. The same prebend was to provide bread and wine for the

celebration of mass in the College; and for the expense of these elements,

he was annually to receive L.4 Scots out of the produce, rents, and revenues

of the rectory and vicarage of Biggar. The fourth prebendary was to have

charge of the poor men, while they were engaged in their devotions in the

College, and also the administration and distribution of the victuals and

other emoluments belonging to them; and was to render an account of the

discharge of his duties, in this respect, to the patron, or, in his absence,

to the provost and prebends. This canon was to receive for his sustentation

L.10 Scots, from the yearly rent of the lands of Drummel-zier, and L.7,

6s.

8d.

Scots, every year, drawn from the produce, rents, and revenues of the

rectory and vicarage of the Church of Biggar. Each of the other prebendaries

was to have for his support the yearly sum of L.17,

6s.

8d

Scots, levied from the revenues of the vicarage and rectory of Biggar, but

the special duties which they were to perfonn are not detailed. One of them

was to be vicar stipendiary of the Parish Church of Biggar, now erected into

a college, and was constantly to take his place in the choir, to sing, and

to exercise his divine office, unless when he was engaged with the special

duties of his charge and the administration of the sacraments. The

presentation of this vicar stipendiary was to belong to the founder and his

heirs, but his collation was to devolve on the Archbishop of Glasgow for the

time being.

The

founder also ordained that there should be attached to the College, in all

time to come, four boys with children’s voices, who were to be sufficiently

instructed and skilled in plain song, invocation, and discant, who were to

have the crowns of their heads shaven, and to wear gowns of a crimson*

colour, after the fashion of the singing boys in the Metropolitan Church of

Glasgow. They were to have, divided amongst them, all and whole the produce

of the priest’s office of the Parish Church of Lenzie, in the diocese of

Glasgow, except so much as might be necessary for the sustentation of a

priest to discharge the duties of the cure of that parish. The presentation

of these boys was to belong to the founder and his heirs, and their

examination and admission to the provost and prebendaries. When they lost

their boyish voices, by advancing age, or when they behaved in a disorderly

and incorrigible manner, the provost and prebendaries were to have the power

of dismissing them from their situations in the College. The produce and

emoluments of the office from which they were to derive their living were,

with the exception already stated, to be under the control of the boys,

along with their

*The word

‘blodie,’ in the original, is rendered by Colvill and other English

gloesarists,1 crimson,1 as derived from the Saxon ‘blod,’

blood; but Dncaoge considers that the proper meaning of it is bln*

parents and relatives, and were to be devoted

exclusively to the payment of their aliment and other necessary expenses.

The

founder ordained that the College should have six poor men, commonly called

(beid men.’ The qualifications for their admission were to be

poverty, frailty, and old age. They were to be natives of the baronies of

Biggar or Lenzie, if a sufficient number could be got in these places, and

they were to reside in the house of the Hospital, with its garden grounds,

which the founder had set aside for their accommodation. They were to be

presented, admitted, and installed by the founder, so long as he lived, and

after his death, by his heirs and successors. They were to be annually

furnished with a white linen gown, having a white cloth hood; and every day,

in all time to come, they were to attend in the College at high mass and

vespers; and when the founder departed this life, they were to sit at his

grave and the grave of his parents, and pray devoutly to the Most High God

for the welfare of his soul, the soul of his wife, and the souls of his

progenitors and successors. For their aliment and support, they were to have

distributed amongst them, on the first day of each month, two bolls of

oatmeal, the whole amounting annually to twenty-seven bolls; so that each

bedesman, during the year, was to obtain four bolls and two firlots of the

said oatmeal. This sustenance was to be levied from the first-fruits and

tithes of the rectory and vicarage of the Church of Biggar; and from the

same source twenty shillings annually was to be drawn for each bedesman, for

purchasing his gown and repairing his house. The bedesmen were also to have

full power, liberty, and access to cast, win, and lead peats and divots from

two dargs of the Nether Moss, in order to supply their hearths with fuel.

The

provost and prebends were to have suitable dwelling-houses and gardens near

the Church. The provost was to have one acre of land for this purpose, and

each canon half an acre; and they were, besides, to have the privilege of

casting, winning, and leading peats in the barony of Biggar, and especially

within the bounds of the lands belonging to the Hospital of St Leonards. The

patron, provost, and prebendaries were, yearly, on the eve of the Feast of

Pentecost, to meet and select two of the prebendaries, whose duty should be

to collect all the produce, tithes, revenues, offerings, and emoluments of

the rectory, vicarage, and church lands of Biggar, and distribute them in

proper order and proportion. Whatever sum remained, after this was done, was

annually to be disposed of in such a way as the patron, provost, and

prebends might think expedient, for the use and advantage of the College.

Each of these prebends, for their services in this respect, was to receive

annually the sum of 26s.

8d

Scots, derived from the revenues of the rectory and vicarage of the Church

of Biggar.

The

founder ordained that the following masses should be celebrated in the

Collegiate Church, and that a register of them should be inscribed on a

board, And suspended in the College* A mass in honour of the blessed Virgin

Mary was to be said in the morning, between six and seven o’clock, before

the commencement of matins, in summer as well as in winter. The priest

celebrating it was not to be exempted from attending and singing at matins;

and if he was not present at the end of ‘Gloria Patri,’ or the conclusion of

the first psalm, he was to lose that hour, and be subjected to a fine. High

mass was to be celebrated immediately after ten o'clock with singing the

solemn Gregorian chant,* or discant, and playing Buch tunes on the organ as

the time might require. A mass was to be said daily to any saint, according

to the option of the oelebrator, immediately after the consecration and

elevation of the body of Christ in high mass, and not sooner; and no priest,

present at chant and high mass, was to absent himself, under the penalty of

losing the hour during which the mass was celebrated.

The

following masses were to be celebrated on week-days, immediately after

matins, viz.:—on

the second day, or Monday, and on the greater double feasts, a mass

de rtquie,

for the founder's soul, his wife’s soul, the souls of his parents, and all

faithful dead; on the third, Tuesday, a mass in honour of St Ann, the mother

of the Virgin Mary; on the fourth, Wednesday, a mass in honour of St

Nicholas and St Ninian,a|> bishops and confessors; on

the fifth, Thursday, a mass in honour of the body of Chriftt; and on the

sixth, Saturday, a mass for the five wounds of Christ; while on Sabbath a

mass was to be performed for the Feast of the Compassion of the Blessed

Virgin Mary.J The officiating priest, elothed in his white gown and

surplice, was, immediately after the celebration of high mass, to approach

the grave of the founder, and sing the psalm, ‘de profundis,’ with the

uateal collects and prayers, and the sprinkling of holy water. Extraordinary

mass, as well as the mass

de

refute, was also to be said daily in the two aisles.

A chapter

was to be held every week in the Collegiate Church. It was to have the same

constitution, and to be subject to the same rules, as the Metropolitan

Church of Glasgow. Whoever absented himself from this meeting was to pay a

fine of twopence. On the fourth day, or Wednesday, immediately after the

solemnities for all the saints, for the purification of the blessed Virgin

Mary, and for the Apostles Philip and James, and St Paul

<ad vmcmla,

a mass was to be sung for the founder’s soul, his wife’s soul, and the souls

of all those previously mentioned,-*—the vespers and matins of the deed

being performed on

*The K/ftnto

Fermo’ was introduced into the service of the Romish Churoh by Pope Gregory

the Great, wfeo flourished daring the sixth centxuy. It has continued in use

to the present dayi *ad is generally known by tbe name of the. Qregorian

Chant

'A

relative of the founder was Prior of the Monastery of St Ninian, at Whithorn

in Galloway.

Compassion of the Virgin, or

wit

Lady of Pity,'—the Friday in Passion Week.

the evening preceding theoe solemnities, along with nine

collects, and nine psalms, with their responses. Each prebend was, with the

Gregorian chant, invocation, and discant, to celebrate matins, high mass,

vespers, and complin, at the hours and seasons usually observed by

prebendaries in other collegiate churches.

All the

prebends and their successors were bound to make a personal residence fit

the College, and on all feast, Sabbath, and week days, and continued

commemorations, were to celebrate and sing, without note, matins, high mass,

vespers, and complin at the great altar in the choir of the Churoh; and,

clothed in their clerical habits— viz., clean linen surplices and red hoods

trimmed with fur,—were, every night after complin, except on the greater

double feasts, to rehearse the responses in honour of the Virgin Mary, to

sing the psalm, ‘de profundis,’ and to read the usual collects and prayers

for the souls of the founder and all faithful dead.

The

prebendaries, at the ringing of the bell, which was to commence every

morning throughout the year at six o’clock, were to meet, clothed in their

clerical vestments, and sing matins at seven. At ten o’clock they were to

perform high mass; and at five, Vespers and complin, except in Lent, when

vespers was to be performed immediately after high mass, and complin at the

usual hour. When met for these purposes, they were not to move up and down

the Church, nor indulge in whispering and laughter, but to the close of the

service were to remain in solemn silence, and to manifest all be* coming

gravity. They were exhorted, in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, to

perform their duties fully, honestly, and attentively; and, avoiding all

light and frivolous proceedings, were to commence, continue, and pause in

the singing all at once. Those who violated this rule were to be severely

punished; for, by singing improperly and carelessly, the due honour of God

was not manifested, the intention of the founder was frustrated, the

well-ordered conscience was hurt, and the edification of others was not

promoted.

The

prebend who absented himself

from

the usual services of the Church on week-days or simple feasts, was, for

each hour, to pay twopence ; on Lord's days and the great feasts, threepence;

and on the higher feasts, fourpence. The fines thus exacted were to be

collected weekly by the provost or a substitute, and were to be expended in

the puJrchase of books or ornaments for the Church. Tbe provost, or his

substitute, was alio to have power of suspending offenders from the chair,

and devoting the whole of their incomes to the uses already stated, or other

objects of piety. On those who persisted in their disobedience, the general

officer of the Church of Glasgow was to inflict still heavier penalties and

higher ecclesiastical censures, from which they were not to be absolved till

they had given the utmost satisfaction. ’

All the

prebendaries were to be priests, or at least in deacorfs orders, and were to

be well skilled in literature, plain song, invocation, and discant; and,

each day, were to take their places at the altars, and in a private manner

celebrate mass for the souls of those by whom these altars were founded.

They were to possess all the advantages common to the Romish Church,

provided they made personal and continued residence at the College; but, in

the event of any one of them absenting himself for five days without

liberty, the provost, or, in his absence, the president and members of the

Chapter, were, unless a necessary cause of absence was shown, to declare his

office de facto

vacant. At their admission, they were to take a solemn oath of obedience to

the provost and the founder, so long as he lived, to observe the statutes

and rules laid down in the constitution and ordinances of the College, and

drawn up and ordained by the founder and others to whom he gave authority.

In the

event of any prebendary being prevented by infirmity or indisposition from

celebrating mass when it was his turn, another of the brethren was to occupy

his place; but should he refuse to perform this service when required by the

provost or president, he was to be fined twelve pence Scots. Should any

prebend be of a quarrelsome disposition, and provoke his brethren to fight,

or engage in other improper contentions, he was, on his offence being

proved, to be removed without further process from his office. A prebendship

becoming vacant in this or any other way, was not to be filled up till after

the lapse of thirty days, so that sufficient time might be afforded for

obtaining a suitable and well-qualified successor, who, previous to his

admission, was to undergo an examination by the provost and prebendaries.

The

charter ends by calling upon Cardinal Beaton, with concurrence of the Lord

Archbishop of Glasgow, to approve, ratify, and confirm, to add, correct, or

otherwise amend, the statutes, rules, and constitution laid down for the

College, its endowments, and officials. Malcolm Lord Fleming, in faith and

testimony of all and every one of the articles stated in connection with his

religious foundation, subscribed the charter with his own hand, and appended

to it his armorial seal; and the Archbishop of Glasgow, and the Chapter of

the Church of Glasgow, in token of their full concurrence and assent,

attached to it their respective seals, on the 10th of January 1545, in

presence of the following witnesses:—William, Bishop of Dunblane ; Robert,

Bishop of Orkney; John, Abbot of Paisley; Thomas, Commendator of Dryburgh;

Malcolm, Prior of Whithorn; William, Earl of Montrose ; John Lord Erskine;

Alexander Lord Livingstone; John Lindsay of Covington; William Fleming of

Boghall; Thomas Kincaid of that Ilk; Andrew Brown of Hartree, and many

others. This charter was confirmed by the Pope's Legate on the 14th of March

1545. The „ charter of confirmation is a very lengthy document, written on

parchment, and is still preserved. |