|

BIGGAR BURN rises in the

north of the parish, and flow? at first in a southerly and then in an

easterly direction. After running a course of about nine miles, it falls

into the Tweed nearly opposite Merlin’s Grave, in the parish of Drummelzier.

On its right bank, near its source, are the lands of Carwood, consisting of

947 Scots acres. At one period they formed a separate feu, and were for many

years, as we learn from documents in the Wigton charter chest, held by a

family of the name of Carwood. The male line becoming extinct, the heiress,

Janet Carwood, was married to a younger son of one of the Lords Fleming, and

the lands continued in this branch of the Flemings for a number of years.

Richard Bannatyne says, that in 1572 they belonged to John Fleming, a

brother of the then Lord Fleming. .They were, at length, greatly encumbered

with debt; and this being cleared off by Lord Fleming, they came back to the

possession of the main branch of the Flemings. They consequently formed part

of Admiral Fleming’s Biggar estate, when the entail of it was set aside in

1830, and almost the whole of it was sold. Carwood, at that time, was

purchased by Mr Robert Gray, son of the Rev. Thomas Gray, Broughton, and for

many years a well-known grocer in Argyle Square, Edinburgh. That gentleman

immediately set to the work of improvement with most laudable vigour. In a

few years he reclaimed 400 acres of muirland, formed 50 enclosures of thorn,

turf, and stone, and planted 200 acres with trees. In 1832 he erected an

elegant mansion-house, and surrounded it with shrubberies and plantations.

Carwood is now the property of W. G. Mitchell, Esq.

On the left side of Biggar

Burn are the lands of Biggar Shields and 'Ballwaistie,’ and a place called

in former times *Betwixt the Hills" They comprise 1132 Scots acres. This

extensive possession belonged at one period to the Fleming family. They

appear to have sold it, or granted a wadset over it, previous to 1677; for,

in November of that year, John Cheisley of Kerswell, near Carnwath, was

retoured heir of his father John, (in the lands and meadow of Scheills and

Betwixt the Hills, a part of the lands called Balweistie, and lands of

Heaviesyde, in the parish of Biggar. In a rent-roll of the Earl of Wigton’s

Biggar property, in 1671, it is stated that the heritor of Biggar Shields

and Betwixt the Hills paid to his Lordship yearly 4 fiftie punds of tiend

duty, and eight bolls of tiend meal.1 It was purchased in 1806 by Mr Joseph

Stain ton, manager of the Carron Company. At that time it was almost wholly

a sheep-walk, and was let at a rent of L.150 per annum. In 1817 and the

three following years, Mr Stainton carried on a series of very extensive

improvements on this estate. ‘ He re claimed 600 acres, drained extensively,

erected 18 miles of stone dykes, and planted 15 miles of thorn hedges, and

265 acres with forest trees. The yearly rental, we suppose, now exceeds

L.1000.

Farther down the stream are

the lands of Persilands, and of what were anciently called the Over and the

Nether Wells, which most likely, by the time of Queen Mary, were disjoined

from the Biggar estate, and held as a separate possession. Some years

afterwards, viz., in 1614, the proprietor of these lands was William

Fleming, no doubt a cadet of the family of the lord superior. In a document

entitled ‘ The Rentall of the mealies, fermes, and other deuties payable to

the Earl of Wigtoun furth of the Barrony of Biggar in 1671,* it is stated

that John Muirhead was heritor of these lands, and paid five merks yearly as

feu-duty. He was succeeded by his son James, who left the lands to George

Muirhead, most likely his son, who died in 1751, and'bequeathed them to his

wife, Mary Dickson, a sister of the Rev. David Dickson, minister of

Newlands. This lady afterwards married the Rev. John Noble of Libberton, and

at her death left the estate of Persilands to her nephew, the Rev. David

Dickson. This divine, after being licensed to preach the Gospel by the

Presbytery of Biggar, was for some time assistant to his aunt’s husband, Mr

Noble. He was afterwards settled at Bothkennar, and ultimately translated to

Edinburgh. He was a very popular preacher, and a strenuous partisan of the

evangelical party in the Church. He died in 1820, and the estate of

Persilands became the patrimony of his son, Dr David Dickson, a

distinguished scholar, philanthropist, and divine, and for nearly forty

years one of the ministers of the West Kirk, Edinburgh. He had thus an

intimate connection with the parish of Biggar; but the pastoral duties and

benevolent schemes with which he was always deeply engrossed, prevented him

from visiting it often, or taking any great interest in its affairs. He died

on the 28th July 1842, and the estate, after continuing a few years in his

family, was sold to Mr Mitchell of Carwood. The farm-house and offices were

recently rebuilt, and a carved stone, containing several initials, the date

1658, and two Latin inscriptions, one of them ‘ Nisi Dominus frustra,* and

very likely belonging to one of the old mansion-houses of the Persilands,

was placed for preservation in the end of a stable.

To the west of the Persilands

is a spot where formerly stood a small farm-steading called Hillriggs.

Towards the end of last century it was occupied by a shepherd of the name of

Kemp. This was the father of George Mickle Kemp, who acquired so great

celebrity as the architect of the Scott Monument at Edinburgh. The architect

was in the habit of stating that he was born here; and we have not as yet

obtained any information to make us doubt that this statement is incorrect.

At all events, he lived here when a child under his father’s roof. In his

tenth year, after his father had gone to reside in another locality, lie

paid a visit to the famed chapel of Iioslin; and being of an impressible and

poetical temperament, he contemplated the pillars, arches, and emblematical

devices of this edifice with wonder and admiration. He was bred to the trade

of a joiner; and on the expiry of his apprenticeship, he set out on a tour

for the purpose of improving himself in his profession, and gratifying his

taste for architectural drawing. He wrought at his trade in many towns of

Scotland, England, and France, and prolonged his stay especially in those

which contained remarkable specimens of Gothic architecture. He was in the

habit of studying all their details, and making a sketch of their chief

peculiarities. He spent also a portion of his time in acquiring a knowledge

of drawing and perspective, in which he made considerable progress.

Kemp at length returned home,

entered into the marriage state, and commenced business on his own account

as a joiner. Not meeting with the success which he expected, he threw aside

the saw and hammer, and devoted himself to the work of architectural

drawing, from which he derived a very small and precarious income. He still

practised his old habits of sketching the remains of ancient castles,

abbeys, etc.; and, in fact, at this time Burns* account of Captain Grose was

strictly applicable to him:—

"By some auld houlet-haunted

biggin,

Or kirk deserted by its riggin,

It's ten to ane yell fin’ him snug in

Some eldrich part.’

He was engaged in taking

sketches of the Abbey of Kilwinning, when a professional friend, whom he

chanced to meet, advised him to try his hand at a design for the monument to

Sir Walter Scott at Edinburgh. Acting on this advice, he hastened home to

his residence in Edinburgh, and in five days produced the design of a

splendid Gothic cross, drawn in its principal details from Melrose Abbey. In

due time he lodged the drawing of his plan, to which he attached the name of

4 John Morvo.* The Committee appointed to forward the monument had offered

prizes for the three best designs; and when they came to decide on the

merits of those submitted for competition, they fixed on John Morvo’s cross

as one of the three to which a prize should be awarded. They were at a loss

to know who John Morvo was, not being aware that the name was assumed, and

that, in fact, it was the designation of a famous mason of former days, who,

in an inscription on Melrose Abbey, is said to have:

"Had in kepyng all mason werk

Of Santandroya, ye Hie Kirk

Of Glasgow, Melroe, and Paslay,

Of Niddiadaill, and of Galway.*

On the morning of the day on

which the prizes were to be decided, Mr Kemp had gone to Linlithgow to take

drawings of some portions of its ruined palace; and on returning in the

evening, he was delighted to find that some person had told his wife that a

prize had been awarded to the design of John Morvo. When it became known

that the beautiful and most appropriate Gothic cross was the production of

so humble and unassuming a man as George Kemp, a strong prejudice was

manifested in some quarters against it, and the Committee at first refused

to adopt it. They advertised a second time for new designs, and a few were

obtained. Kemp stuck to his cross, and gave in an improved drawing of his

original plan. The Committee still hesitated and objected. It was alleged to

be a mere copy of some Gothic building, and to be of so inaccurate and

unsubstantial a construction, that it even could not be erected. Mr Kemp

himself satisfactorily showed that the first charge was entirely without

foundation ; and in regard to the second, Mr Burn, a professional architect

of high reputation, who was consulted by the Committee, declared ‘ his

admiration of Mr Kemp's design, its purity as a Gothic composition, and more

particularly the constructive skill exhibited throughout, in the combination

of the graceful features of that style of architecture, in such a manner as

to satisfy any professional man of the correctness of its principle, and the

perfect solidity which it would possess when built.’ The Committee were,

therefore, induced, in March 1838, to recommend the adoption of Mr Kemp’s

plan, as ‘ an imposing structure, 135 feet in height, of beautiful

proportions, in strict conformity with the purity in taste and style of

Melrose Abbey, from which it is in all its details derived.’ It was

afterwards resolved, in order to give a still more impressive effect to the

structure, to enlarge it to the height of 200 feet above the surface of the

ground.

The building of the monument

was entrusted to Mr David Lind, and Mr Kemp himself was appointed

superintendent of works. Mr Kemp was now placed in circumstances of

comparative comfort; he had acquired a celebrity which he had hardly dared

at one time to contemplate, and he had the prospect of being largely

employed, and raised to a state of affluence. Unfortunately, one dark night

when on his way home, he fell into the Union Canal, and was drowned. Mr Kemp

was a remarkably modest and unassuming individual. He was averse to anything

like forwardness and obtrusion. His merits were thus not readily observed,

and often failed to secure him that attention to which he was entitled. He

was of a social disposition. He loved to spend an hour with a friend to

discuss the progress of art, or the topics of the day. He had cultivated his

mind with some assiduity, and wrote tolerably good versos, some of which

appeared in newspapers and periodicals. His architectural genius was of a

high order. Ilis Scott Monument was a noble conception, and will perpetuate

his name to distant ages. It holds, and is likely long to hold, a chief

place amid the splendid structures that adorn the capital of* our native

land.

A little farther down is the

farm of Foreknowes and Rawhead, which some years ago belonged to the Hon.

Mountstuart Elphinstone. a brother of Admiral Fleming, and well known as a

Governor of Bombay, and afterwards of Madras, and as the author of an

interesting work on the Kingdom of Cabul. He retired from the offices which

he held in India in 1827, and died at Hookwood Park, Surrey, o‘ii the 20th

November 1859. This property was purchased from Mr Elphinstone by Mr

Gillespie of Biggar Park, and sold by him to the Free Church College,

Edinburgh, having been purchased with funds bequeathed for the benefit of

that institution.

We next come to the mill

which has ground the meal and malt of the parishioners for a long period, as

it is mentioned in some very old documents connected with the parish. It is

also referred to in one of Dr Pennicuick’s Poems, published upwards of one

hundred and fifty years ago, entitled ‘The Tragedy of the Duke of Alva,

alias Gray beard; being the complaint of the brandy bottle lost by a poor

carrier, having fallen from the handle, and found again by a company of the

Presbytery of Peebles, near Kinkaidylaw, as they returned from Glasgow

immediately after they had taken the test.’ The graybeard, address ing their

reverences, said,

‘O sons of Levi! messengers of

grace!

Have some regard to my old reverend face,

My broken shoulder and my wrinkled brow

Plead fast for pity, and supply from you.

Help, godly sirs ; and, if it be your will,

Convey me safely home to Biggar Mill,

Where, wand’ring to the widow, I was lost.

Alas! I fear the Carrier pays the cost.

In spite of these and other

sympathetic appeals, the holy brethren resolved that they would regale

themselves with the inspiring contents of the graybeard, let the

consequences be what they might.

'Right blythe they were, and

drank to ane another,

And ay the word went round, Here’s to you, brother.’

The. poor widow of Biggar

Mill was thus deprived of her jar of brandy, and in all likelihood the

carrier had to pay the expense of the carouse.

Biggar Burn, a little above

the mill, enters a deep ravine called the Burn Braes, and, after passing the

mill, flows along in serpentine meanders, like the Links of Forth in

miniature. On the right bank are the ruins of the wauk mill and dyeing

establishment of Thomas Cosh, and his son-in-law Angus Campbell, and the

picturesque suburb of Westraw, with its finely sloping gardens. The

indwellers in Westraw were wont to reckon themselves a sort of separate

community from the inhabitants of the town of Biggar. They had distinct

societies and coteriea of their own. They had their own peatmoss, their own

birlemen, and their own amusements. Between the boys of the two places there

was a standing feud of old date. This was constantly manifesting itself in

pugilistic encounters; but at a certain season of the year it broke out in a

general bicker or melee on the Burn Braes. The weapons employed were slings,

stones, and sticks. The tact and heroism at times displayed in attacking and

defending these braes, would have done no discredit to a regular army. The

wounds inflicted were often severe, and sometimes left scars and injuries

that the sufferers carried with them to the grave. The baron bailie, Mathew

Cree, and his henchmen the chief constables of the town, sometimes made a

sally on the belligerents; and it was a rare sight to see these worthy

powers put to flight by repeated volleys of stones, or at other times

forcing the youthful warriors to shift their ground, and take refuge behind

the mill-planting, or to scatter themselves over Cuttimuir or Kennedy’s

Oxgate. A lad having lost an eye in one of these encounters, the better

disposed portion of the inhabitants at length rose against them, and happily

succeeded in putting a stop to them, it is to be hoped, for ever.

The lands behind the Westraw

swell into a gentle upland, now crowned with trees, called the Knock. These

lands belonged at one time to the Knights Templars. So late as the 20th of

March 1620, we find a precept of Sasine granted to John Smith, of two

oxgates of Templelands, with the annuals or teinds thereof, in the Westraw

of Biggar. In former times, it was a common thing to hold and compute land

by oxgates. In the old writs of Biggar, of which there are a large number in

the Wigton charter chest, we notice references to the following oxgates:—Chamberlain’s,

Fleming’s, Goldie’s, Hillhead, Mosside, Smith’s, Spittle, Staine, Stainehead,

and Telfer’s. The lands of Westraw, or 1 Waaterraw,’ as it is often called

in the old writs, consisted of eight oxgates. These oxgates were, in 1671,

possessed by Archibald Watson, Thomas, James, William, and Alexander Robb,

and William Valange, who ‘payd for ilk oxgang twentie punds;’ ane boll of

meall, ane boll of beer, and ane boll and half of hill oats,’ and for the

whole twenty-four kain fowls.

On the left bank are the

Kirkhill, the Kirk and the Kirkyard, the Moat-knowe, and the Preaching Brae.

The Preaching Brae is the spot at which open-air discourses were delivered

on sacramental and other extraordinary occasions. The tent was pitched near

the edge of the Burn, and the crowd rose rank above rank on the rising

ground in front. Many of the chief Dissenting divines of Scotland,

especially those of former generations, preached here, and attracted

immense multitudes from the

country round. The clergy, at these assemblies, generally put forth their

best abilities. Many persons were wont to date from them their first serious

concern for their eternal interests. The spectacle was reverential and

picturesque, reminding one of the conventicles of old, to see a large throng

of people worshipping their Creator under the blue canopy of heaven; and the

heart was touched to hear ‘the sweet acclaim of praise’ arise from thousands

of pious lips, and swell on the fitful breeze. Hie practice of preaching

here has been discontinued for well nigh forty years, so that few of the

present generation of Biggar inhabitants have seen a Bum Brae conventicle at

all approximating in magnitude and rapt devotion to those of former times.

On these braes the

inhabitants have long carried on the practice of washing and bleaching their

clothes. Attempts have several times been made to deprive them of this

privilege. A keen war has hence arisen between them and the tacksmen of the

grounds; but the result has hitherto been, that the wives and maidens have

remained in possession of the field.

A little farther down is a

level spot called Angus's Green, on which the Biggar gymnastic sports are

annually held in the middle of June. These sports have hitherto been

popular, and have been largely patronized; but, like similar amusements in

other parts of the country, they are understood to be now on the wane, and,

unless their patrons make vigorous efforts to uphold them, the probability

is that ere long they will be abandoned. The curious excavations here, in

connection with the Moat-knowe, have, unfortunately, in the desire for

improvement, been filled up and defaced.

A little farther down, some

thirty years ago, stood the hut of Janet Watson, commonly known by the name

of ‘Daft Jenny.* She was the daughter of John Watson and Isabella Vallance.

In her early days she was employed in hawking small wares about the country,

in a basket; but at length, manifesting decided symptoms of insanity, she

was placed in confinement, became dependent on the parochial funds, and

lived here in her solitary apartment for many years. Her appearance was most

singular. She had a wild and excited expression of countenance. She was

commonly dressed in a blue cotton gown, or in a blue flannel petticoat and

jupe, or short-gown. She wore on her head a plain mutch, or ‘toy,’ as it was

here called, while on one shoulder hung a plaid; and in her left hand she

invariably held an old tobacco pipe and a tattered Bible, which she

frequently kissed or held to her breast. She was fastened by the leg with a

strong iron chain, to prevent her from making her escape, and committing

injury on the persons and property of the inhabitants. Her language was

rambling and incoherent, and largely interlarded with snatches of songs,

texts of Scripture, and the names of persons with whom she had been

acquainted. At times it was uttered in a low and subdued tone, and all of a

sudden it was poured forth with a vehemence and excitement that made all the

neighbourhood re-echo. She was somewhat outrageous. She would heave the

parritch cog, the frying pan, and other utensils in which she received her

food, over the top of the adjacent houses, and assail persons who came near

her with sticks and stones. When she broke her chain, or contrived to slip

it off her leg, she commonly ran to the Relief Manse, erected on the site of

her father's cottage; and there she broke the windows, or pulled up the

bushes and plants in the garden. She was thus a great terror to the juvenile

population; and when the cry arose, ‘Jenny’s loose/ every boy and girl made

speedily to a place of protection.

Her father, surnamed the

‘Whistling Laird,’ was a singular sort of a man. In his early days he had

spent some time in North America, and had there acquired a habit of making

various articles of domestic use. In the side of a brae, near the place at

which his daughter’s hut stood, he erected a curious and primitive-looking

building of stones, turf, and wood, and covered it with a roof composed

partly of paper and pitch, and hence it was commonly known by the name of

the ‘ Castle o’ Clouts.’ He made the whole of his own clothes, including his

shoes and leathern cap; and he produced some rare pieces of joiner’s work,

in the shape of carts, wheelbarrows, etc. His first wife, Isabella Vallance,

died early; and, during the war in Spain, he married a woman commonly called

‘ Jock’s Jenny,’ who had been previously married to a labourer in Biggar, at

one time well known in that town by the soubriquet of 4 Whistling Jock,’

from a bumming sort of whistle in which he indulged as he went from one

place to another. During the exciting times of the Continental War,

‘Whistling Jock’ was fired with the ambition of being a soldier; so he

deserted his wife, and went to fight the battles of his country in the

Spanish Peninsula. He very likely carried on little epistolary

correspondence with his wife, even when he first went abroad, but at length

it ceased altogether; and as his regiment had frequently been engaged with

the enemy, Jenny suspected that he had lost his life in some of the

sanguinary contests then so common in Spain. She wrote a letter inquiring

after him to the War Office, and, by some mistake or other, he was reported

to have been killed. When the Whistling Laird, therefore, made proposals of

marriage to her, she considered she was at liberty to accept them, as she

said, in her stuttering manner, ‘The War Office had told her that Dock was

killed at Pain, far ayont Gasco.’ They therefore were joined in wedlock, and

Hved contentedly till the conclusion of the war, when ‘Dock’ suddenly made

his appearance in his tattered regimentals, and confronted the astounded

pair. Jenny would rather have preferred to live with ‘Don,’ as she called

her husband number two, as, in her estimation, ‘he was a good religious

man;’ but Whistling Jock maintained, that, by priority of engagement, he had

a preferable claim. With threats and pleadings, Jenny was prevailed on to go

with Dock, and the Whistling Laird was left in solitary blessedness for the

remainder of his life.

John Watson was a person of

sagacity and information. He allowed himself, however, on one occasion, to

be made the victim of a rather laughable, though to him a very mortifying

hoax. One day he received by post a large letter with a huge seal,

purporting to be from the Provost and Magistrates of Edinburgh, and inviting

him to accept of the office of hangman, then vacant by the death of John

High. He was not only thoroughly convinced that the letter was genuine, but

he was vastly elated at the idea of receiving so great a mark of attention

and honour from the municipal authorities of the Scottish metropolis. He

said the post which they had conferred on him might not in general

estimation be held to be very respectable, yet it was most necessary, and

therefore laudable; because, if the laws were not duly carried out, society

would soon be thrown into a state of anarchy. In spite of the remonstrances

of his friends, he set out to Edinburgh, and presented himself at the

Council Chambers. He boldly announced that he had come from Biggar to accept

of the office of hangman. The clerks in the office informed him that it had

already been filled up. This sad announcement at once laid all his bright

hopes in the dust. He declared that he had been very unfairly treated, and

produced the document putting the office in question at his acceptance. The

communication was declared to be an arrant forgery, and John had no other

alternative than to trudge back to Biggar, it may be a wiser, but certainly

a most angry and disappointed man.

A little farther on are the

Gras Works, erected in 1839 by a joint-stock company. Gas is supplied to the

community at 7s. per 1000 cubic feet. The undertaking, while it has been a

great advantage to the inhabitants, has also been a profitable speculation

for the shareholders. We have next on the side of the Bum a range of

premises used as & brewery by James Steel, and afterwards by Mr James Bell.

No brewing has been carried on here for several years. Adjoining is the Wynd,

dear to the recollection of Westraw callants, when it was tenanted by such

worthies as John Davidson, tailor; David Loch, and Andrew Steel, carters,

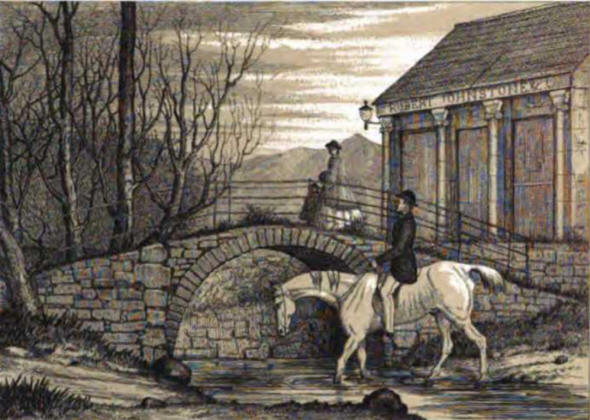

etc. Here is the Cadger’s Brig, supposed to be a Roman work. It is far from

unlikely that the Romans threw a bridge across this stream, which often in

winter is considerably swollen, and is then not easily fordable; but the

present erection is perhaps more modem. By whatever party it was built, it

was, no doubt, largely taken advantage of by the numerous cadgers that at

one time passed through Biggar to the great mart for their merchandise, the

Scottish capital; and hence, in all likelihood, its name. The popular

tradition, however, is, that it first received its name from the

circumstance of its having been used by Sir William Wallace, when he visited

the English camp at Biggar in the guise of a cadger. It is very narrow, and

being without parapet-walls, it was crossed with great difficulty in dark

nights. About forty years ago, a substitute for these walls was found in an

iron railing, which was erected under the auspices of Mr James Bell, brewer.

A little below is a bridge in connection with the turnpike road to Dumfries,

built in 1823, and embanked at each end with the earth that formed the

Cross-knowe.

Cadger's Brig

Below these bridges is the Ba’

Green, supposed af one time to have been the public park of the town, where,

among other pastimes, football was played. Football was long a favourite

amusement in this as well as in other districts of Scotland. It was cried

down by the edicts of James I., and other sovereigns, who wished to

substitute archery in its place; but it still prevailed. It was a rough and

savage pastime. Severe wounds were often inflicted from falls and kicks, and

fights were not uncommon from alleged instances of unfair play. The sport

was also carried on in the Main or High Street of Biggar, particularly on

public occasions, when a number of the country people were in town.

It was then most irregular

and tumultuous. Every one took what side he pleased. The fury and violence

were terrible. A dozen or two of the combatants would be lying sprawling on

the ground at one time, and an unhappy wight would be knocked through a

window, or overturned in a filthy open sewer. This pastime has been

discontinued. Draughts, quoits, curling, and bowling, are now the favourite

amusements. The Bowling-green lies contiguous to the Moat-knowe. It is

neatly constructed, is kept in excellent order, and conduces much to the

recreation and health of a portion of the inhabitants.

On the side opposite to the

Ba’ Green is the small holding of the Blawhill; and here, by the side of the

stream, is Jenny’s Well, to which the inhabitants established a right about

thirty-five years ago, when an attempt was made to shut up the road to it by

the proprietor of the adjoining grounds. The meeting of Westraw wives, with

Mr James Bell, brewer, at their head, to defend their ancient light, was , a

fine display of indignant and independent Biggar feeling. The proprietor

entered the case before the Sheriff at Lanark; but in the end had sense

enough to withdraw it, and pay all expenses. So this remarkably cool and

copious spring will remain in all time coming to supply refreshing draughts

to the Biggar people, and to remind them that in this free country might

cannot always triumph over right.

On the right are the lands of

Boghall Mains, now finely subdivided and improved. The farm-steading, built

about thirty years ago, is one of the most elegant and substantial in the

county. It cost the proprietor L.1500, and the tenant L.800 in cartages.

Biggar Burn, after receiving

a small stream from Hartree, takes the name of Biggar Water. The first

reference to Biggar Water in any of our public muniments, so far as we have

observed, is in a document giving a detail of the perambulation of the

Marches of Stobo, which is supposed to have taken place between 1202 and

1207. This document, after referring to various boundaries of that parish,

goes on to say, And so by the hill top between Glenubswirles to the Bum of

Glenkeht (the Muirbum), and so downwards aa that Bum falls into the Bigre.’

The other tributaries of Biggar Water are Skirling Burn, Kilbucho Bum,

Broughton Bum, and Holmes Water. In a ditch or small bum running from the

Westraw Moss, the strange phenomenon is sometimes seen* of a portion of the

waters of the Clyde flowing into Biggar Water. This, of course, only takes

place when the Clyde is greatly flooded; but it shows how small an effort

would be requisite to turn the waters of Clyde into those of the Tweed. At

the place where the level is most favourable for such a project, the Clyde

has actually formed a channel of some length in this direction. The

tradition regarding it is, that the wizard, Michael Scott, entered into a

paction with the devil, by which he obtained liberty to take the Clyde

across the Westraw Moss and the lands of Boghall as fast as a horse could

trot, on condition, however, that he would not look behind him during the

operation. He commenced the work; but the angry waters made such a terrific

noise, that he could not resist the temptation to look back to see the cause

of the uproar. The spell was thus broken, and the waters fled back to their

old channel, but left a very decided trace of the devious course which they

had been forced to take.

The Symington, Biggar, and

Broughton Railway passes along the valley of Biggar Water. The first sod of

this line was cut on the 30th of September 1858, by Mrs Baillie Cochrane of

Lamington, amid the applauding demonstrations of a great concourse of

spectators, who had marched to the spot from Biggar with banners and bands

of music. It was opened on the 5th of November 1860. The length of it is

little more than eight miles; and the tract over which it passes, being

extremely level, presented little engineering difficulty It crosses the

Clyde, near the Moat of Wolf-Clyde, by a viaduct, the piers and abutments of

which are of stone, and the arches, seven in number, of malleable iron.

Three of the arches are each 62£ feet wide, and are what are called ‘

lattice ’ girders; and the other four are each 27 feet wide, and are called

‘ plate ’ girders. The whole weight of iron employed is 44 tons, and the

cost was L.4150. At this point is the first station, the second is at

Boghall, the third is at Braidford Bridge, and the present terminus is at

Broughton, but steps are in the course of being taken to carry the line down

the Tweed to Peebles. This railway can hardly fail to confer a great benefit

on the district, in conveying agricultural products to the marts in the east

and west, and in bringing coals, lime, and other articles which the district

requires.

The tract through which

Biggar water flows, especially on its north bank, was till recently a

dreary, unprofitable, and deleterious waste, relieved only here and there

with a stunted birch tree. It was composed of peat-moss, and vast quantities

of peat for fuel had been dug here. The surface was consequently studded

with deep excavations, filled with water, and almost impassable. When a

stray stot or stirk ventured to intrude into this boggy and treacherous

track, the probability was, that it plunged into a deep hole, or stuck fast

in the mud; and then great was the labour of men and boys to drag it from

its dangerous position, and preserve it from destruction. This waste appears

to have been in early times called the Nether Moss, and latterly it was

known by the name of Biggar Bogs. In 1832, a poem appeared in a periodical

called the 'Edinburgh Spectator,’ which contained a sort of ironical

eulogium on the Bogs of Biggar. One of the stanzas ran thus:—

1'Othe Bogs of Biggar

Both clean and trig are,

With the frogs a chirping

Uncommon sweet;

And some bulrushes,

And stunted bushes,

To meet your wishes,

So small and neat.'

The growing crops in the

neighbourhood of this dismal swamp, except in early years, were very liable

to be damaged by frost, and were thus often rendered unfit for seed, and

sometimes even for food. The feuars of Biggar, who rented nearly all the Bog

parks, were occasionally subjected to heavy losses from this cause. The late

Rev. William Watson, incumbent of the parish, had one of the Bog parks; but

in consequence of the soil being drier, and lying at a greater distance from

the swampy ground, his crops generally suffered less damage from the frosts

than some of his neighbours, and thus excited their envy. One very frosty

autumnal morning, Mr Watson met the late William Clerk, merchant, Biggar,

and accosting him, said,

'William, this is a snell

morning; I am afraid the oats in the Bog parks must have sustained damage.*

*Aye, Mr Watson,' was the reply, 'there's nae respect o’ persons this

morning.'

Various efforts were, from

time to time, made to bring some portions of this tract under cultivation.

The great difficulty to contend with was the want of a sufficient descent,

to carry off the superfluous moisture with which the lands were saturated.

The whole valley was nearly a dead level, and the channel of Biggar Water

was only a few inches below the surface. Drains, cut to any depth, were

worse than useless. They only had the effect of bringing water in greater

abundance on the adjoining grounds. To obviate these obstructions to

drainage, the late Mr Murray of Heavyside cut a large ditch parallel to the

stream, but at some distance from it, and at the termination of the ditch

erected a water-wheel, with buckets, by which he lifted the water to a

higher elevation, and thus was enabled to dry a considerable portion of his

bog lands. This wheel, which wrought very effectually, was the workmanship

of the ingenious millwright of Biggar, Mr James Watt. The adjoining

proprietors at length resolved to deepen Biggar Water to such an extent as

to ensure a proper declivity, and prevent it from being filled up with mud

and weeds, as had hitherto been the case. This important work was,

accordingly, carried out under the superintendence of Mr George Ferguson,

and completed in 1858. Some hundred acres of land along the banks of the

stream have, consequently, been drained and cultivated, and are now annually

covered with most luxuriant crops, while the atmosphere around has been

rendered vastly more salubrious and agreeable.

In this dreary flat stood a

hamlet called John’s Ilolm. John (iaims and Archibald Brown were two of the

tenants of this place, a hundred and thirty years ago. The buildings have

now entirely disappeared, so that it is difficult to ascertain the exact

spot on which they stood.

This level tract was, no

doubt, at a very remote period, covered with the sea. The stones, to a great

depth, appear to have travelled from a distance, and have the smooth rounded

shape that is produced by the action of water. Mr Robert Chambers, in his

curious and interesting work on ‘Ancient Sea Margins,’ states, that the

central mountain range of southern Scotland, from which the Tweed and Clyde

take their almost contiguous origin, bears marks of ancient sea levels at

coincident heights on both sides. He enumerates various places at the height

of 628 feet on the Ettrick, Gala, and Tweed, which present flat projections,

supposed to be formed by the action of the sea, and then says, * It is

remarkable, however, that the broad passage or col between the Tweed and

Clyde at Biggar, much of the basis of which is occupied by a moss, is given

at 628 feet above the sea. When the sea stood at this height, the two

estuaries of Clyde and Tweed joined in a shallow sound at Biggar, and the

southern province of Scotland formed two islands, or rather group of

islands.’

It is a matter of some regret

that the Fleming family, so long connected with this parish, have, from time

to time, disposed of nearly all the extensive lands that they once possessed

here and in the neighbourhood. With Glenholm, Kilbucho, and Thankerton they

have long ceased to have any connection, and the whole of their inheritance

in the parish of Biggar has now dwindled down to a few acres. This regret is

qualified by the circumstance, that they had long allowed their lands in

this parish to remain in a very neglected state. They held out no inducement

to improvement. Being nonresident, and possessed of little superfluous

wealth, they neither showed any example of activity, nor expended the

necessary capital to promote the due cultivation of the soil; and thus it

continued, from year to year, in the same dismal and unprofitable state.

When the entail was broken, fully thirty years ago, and the portion of

Biggar parish which they still held was sold, it fortunately fell into the

hands of men who lost no time in commencing the work of improvement. New

farm-steadings were built, drains were cut, dykes were erected, and trees

and hedgerows were planted. Two thousand acres of land, by the enterprise

and resources of the new proprietors, Lord Murray of Langlees, George

Gillespie, Esq. of Biggar Park, Robert Gray, Esq. of Carwood, Thomas Murray,

Esq. of Heavyside, and William Murray, Esq. of Spittal, very soon assumed a

new appearance, and became vastly more valuable.

The whole lands in the parish

of Biggar comprise, as we have said, 5852 Scots acres. The soil consists

principally of clay, sand, gravel, loam, and peat-moss. It rears good crops

of oats, barley, pease, turnips, and potatoes, but is not adapted for beans

and wheat. The dairy is here an object of great attention. Most of the

farmers keep a stock of milk cows; and the butter and cheese, both full milk

and skim milk, which they produce, are held in high repute in the marts of

the eastern and western metropolis, and very often receive premiums at the

shows of the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland. In the north

part of the parish, near the source of Biggar Burn, the soil is of a poor

description, and appears to be too scantily supplied with the phosphates

that are necessary for strengthening and fertilizing the soil. It is

supposed that it is from this cause that the cattle are often attacked with

a disease called the ‘stiffness,’ or ‘cripple.* Those persons who wish to

obtain information regarding this disease, which has hitherto been little

investigated in this country, are referred to an article ‘On Arthritic or

Bone Disease,* by Mr William Thorburn, Henchilend, in the January number of

the ‘Veterinary Review* for 1861, and to various observations on the subject

by Mr John Gamgee, both in that periodical and in his work on ‘The Domestic

Animals in Health and Disease.* |