|

MY father was born in 1793,

and my mother in 1802, in Putnam County, State of New York. Their names

were John and Melinda Nowlin. Mother's maiden name was Light.

\Iv father owned a small

farm of twenty- five acres, in the town of Kent, Putnam County, New

York, about sixty miles from New York City. We had plenty of fruit,

apples, pears, quinces and so forth, also a never failing spring. He

bought another place about half a mile from that. It was very stony, and

father worked very hard. I remember well his building stone wall.

But hard work would not

do it. He could not pay for the second place. It involved him so that we

were in danger of losing the place where we lived.

lie said, it was

impossible for a poor man to get along and support his family; that he

never could get any land for his children there, and he would sell what

he had and go to a better country, where land was cheap and where he

could get land for them.

He talked much of the

territory of Michigan. He went to one of the neighbors and borrowed a

geography. [Jedediah Morse, "father of American geography," was the

father also of Samuel F. B. Morse, inventor of the electric telegraph.

While still in his early twenties, Morse produced in 1784 the first

geography published in the United States. Various geographies and

gazetteers in a variety of editions followed and their acceptance by the

public was such that throughout the author's lifetime his geographies

"virtually monopolized their field in the United States." Presumably the

work consulted by Nowlin was one of the many editions of The American

Universal Geography.] recollect very well some things that it stated. It

was Morse's geography, and it said that the territory of Michigan was a

very fertile country, that it was nearly surrounded by great lakes, and

that wild grapes and other wild fruit grew in abundance.

Father then talked

continually of Michigan. Mother was very much opposed to leaving her

home. I was the eldest of five children, about ten or eleven years of

age, when the word Michigan grated upon my ear. [Wi!liam Nowlin was born

Sept. 25, 1821. This statement would indicate that the family talk about

Michigan began about 1831 or 1832. The migration was made in 1833-34.] I

am not able to give dates in full, but all of the incidents I relate are

facts. Some of them occurred over forty years ago, and are given mostly

from memory, without the aid of a diary. Nevertheless, most of them are

now more vivid and plain to my mind than some things which transpired

within the past year. I was very much opposed to going to Michigan, and

did all that a boy of my age could do to prevent it. The thought of

Indians, bears and wolves terrified me, and the thought of leaving my

schoolmates and native place was terrible. My parents sent me to school

when in New York, but I have not been to school a day since. My mother's

health was very poor. Her physician feared that consumption of the lungs

was already seated. Many of her friends said she would not live to get

to Michigan if she started. She thought she could not, and said, that if

she did, herself and family would be killed by the Indians, perish in

the wilderness, or starve to death. The thought too, of leaving her

friends and the members of the church, to which she was very much

attached, was terribly afflicting. She made one request of father, which

was that when she died he would take her back to New York, and lay her

in the grave yard by her ancestors.

Father had made up his

mind to go to Michigan, and nothing could change him. He sold his place

in 1832, hired a house for the summer, then went down to York, as we

called it, to get his outfit. Among his purchases were a rifle for

himself and a shot gun for me. He said when we went to Michigan it

should be mine. I admired his rifle very much. It was the first one I

had ever seen. After trying his rifle a few days, shooting at a mark, he

bade us good-by, and started "to view" in Michigan.

I think he was gone six

or eight weeks, when he returned and told us of his adventures and the

country. He said he had a very hard time going up Lake Erie. A terrible

storm caused the old boat, "Sheldon Thompson" [The Sheldon Thompson was

not an old boat in 1833 (the probable date of this journey, rather than

1832), but it may well have seemed so to the passenger, unfamiliar with

the conditions surrounding early steam boat navigation on the Great

Lakes. From 1818 to 1826 there was but one steam vessel on Lake Erie—the

Walk-in-the-Water, 1818-22, and the Superior, 1822-26. Several small

steamboats were built in the latter year, the Henry Clay, William Penn,

Niagara, and Enterprise. The Sheldon Thompson was built at Huron in

1830, and in August made her first trip to Mackinac and Green Bay. The

vessel, of 242 tons burden, had three masts, being the first steamer of

this type on the Upper Lakes.] to heave, and its timber to creak in

almost every joint. He thought it must go down. He went to his friend,

Mr. George Purdv, (who is now an old resident of the town of Dearborn)

said to him: "You had better get up; we are going down! The Captain says

'every man on deck and look Out for himself.'" Mr. Purdy was too sick to

get up. The good old steamer weathered the storm and landed safely at

Detroit.

Father said that Michigan

was a beautiful country, that the soil was as rich as a barnyard, as

level as a house floor, and no stones in the way. (I here state, that he

did not go any farther west than where he bought his land.) He also said

he had bought eighty acres of land, in the town of Dearborn, two and a

half miles from a little village, and twelve miles from the city of

Detroit. Said he would buy eighty acres more, east of it, after he moved

in the spring, which would make it square, a quarter section. He said it

was as near Detroit as he could get government land, and he thought

Detroit would always be the best market in the country.

Father had a mother,

three sisters, one brother and an uncle living in Unadilla Country

[Apparently first printed "Unadilla Country," and later corrected to

"County." There is no Unadilla County, but the village of Unadilla is in

southwestern Otsego Counts', on the Susquehanna River. This is but one

of several curious type corrections in the book which must have been

made by the printer. The method employed was that of pasting over the

erroneous spelling a tiny piece of paper on which the correct letters

were printed. The pasting was done by hand, and usually the letters thus

supplied are noticeably out of line.] N. Y. He wished very much to see

them, and, as they were about one hundred and fifty miles on his way to

Michigan, he concluded to spend the winter with them. Before he was

ready to start he wrote to his uncle, Griffin Smith, to meet him, on a

certain day, at Catskill, on the Hudson river. I cannot give the exact

date, but remember that it was in the fall of 1833.

The neighbor, of whom we

borrowed the old geography, wished very much to go West

with us, but

could not raise the means.

When we started we passed

by his place; he was lying dead in his house. Thus were our hearts,

already sad, made sadder.

We traveled twenty-five

miles in a wagon, which brought us to Poughkeepsie, on the Hudson river,

then took a night boat for Catskill where uncle was to meet us the next

morning. Before we reached Catskill, the captain said that he would not

stop there. Father said he must. The captain said he would not stop for

a hundred dollars as his boat was behind time. But he and father had a

little private conversation, and the result was he did stop. The captain

told his men to be careful of the things, and we were helped off in the

best style possible. I do not know what changed the captain's mind,

perhaps he was a Mason. Uncle met us, and our things were soon on his

wagon. Now, our journey lay over a rough, hilly country, and I remember

it was very cold. I think we passed over some of the smaller Catskill

Mountains. My delicate mother, wrapt as best she could be, with my

little sister (not then a year old) in her arms, also the other

children, rode. Father and I walked some of the way, as the snow was

quite deep on the mountains. He carried his rifle, and I my shot-gun on

our shoulders. Our journey was a tedious one, for we got along very

slowly; but we finally arrived at Unadilla. There we had many friends

and passed a pleasant winter. I liked the country better than the one we

left, and we all tried to get father to buy there, and give up the idea

of going to Michigan. But a few years satisfied us that he knew the

best.

Early in the spring of

1834 we left our friends weeping, for, as they expressed it, they

thought we were going "out of the world." Here I will give some lines

composed and presented to father and mother by father's sister, N.

Covey, which will give her idea of our undertaking better than any words

I can frame:

"Dear Brother and Sister,

we must bid you adieu,

We hope that the Lord will deal kindly with you,

Protect and defend you, wherever you go,

If Christ is your friend, sure you need fear no foe.

The distance doth seem

great, to which you are bound,

But soon we must travel on far distant ground,

And if we prove faithful to God's grace and love,

If we ne'er meet before, we shall all meet above."

About twenty years later

this aunt, her husband and nine children (they left one son)

sons-in-law, daughters-in-law and grand-children visited us. Uncle had

sold his nice farm in Unadilla and come to settle his very intelligent

family in Michigan. He settled as near us as he could get government

land sufficient for so large a family. With most of this numerous family

near him, he is at this day a sprightly old man, respected (so far as I

know) by all who know him, from Unionville to Bay City.

Now as I have digressed, I must go back and

continue the story of our journey from Unadilla to Michigan. As soon as

navigation opened, in the spring, we started again with uncle's team and

wagon. In this manner we traveled about fifty miles which brought us to

Utica. There we embarked on a canal boat and moved slowly night and day,

to invade the forests of Michigan. Sometimes when we came to a lock

father got off and walked a mile or two. On one of these occasions I

accompanied him, and when we came to a favorable place, father signaled

to the steersman, and he turned the boat up. Father jumped on to the

side of the boat. I attempted to follow him, did not jump far enough,

missed my hold and went down, by the side of the boat, into the water.

However, father caught my hand and lifted me out. They said that if he

had not caught me, I must have been crushed to death, as the boat struck

the side the same minute. That, certainly, would have been the end of my

journey to Michigan. When it was pleasant we spent part of the time on

deck. One day mother left my little brother, then four years old, in

care of my oldest sister, Rachel. He concluded to have a rock in an easy

chair, rocked over and took a cold bath in the canal. Mother and I were

in the cabin. When we heard the cry "Overboard!" we rushed on deck, and

the first thing we saw was a man swimming with something ahead of him.

It proved to be my brother, held by one strong arm of an English

gentleman. He did not strangle much; some said the Englishman might have

waded out, in that case he would not have strangled any, as he had on a

full-cloth overcoat, which held him up until the Englishman got to him.

Be that as it may, the Englishman was our ideal hero for many years, for

by his bravery and skill, unparalleled by anything we had seen, he had

saved our brother from a watery grave.

That brother is now the John Smith Nowlin,

of Dearborn. [John Smith Nowlin, the subject of this adventure, was born

in Putnam County, New York, June 13. 1829, and died at Burlingame,

Kansas, November i, 1902. He was twice married, and several of his

children still live in Detroit. He spent the later half of his life in

Kansas, saving a three-year period following the death of William Nowlin

in 1889, when he returned to Michigan to operate the farm left by the

latter to his heirs.]

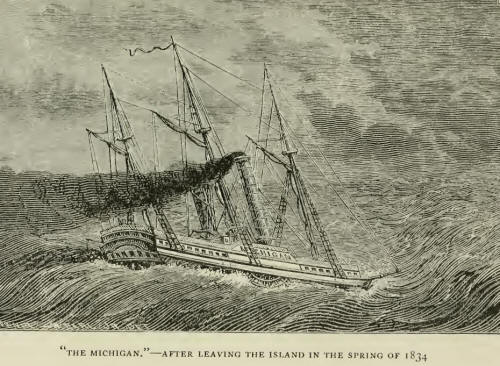

Nothing more of importance occurred while we

were on the canal. When we arrived at Buffalo the steamer, "Michigan,"

[The Michigan was launched at Detroit in 1833, and until 8837 was

regarded as the finest steamer on the Upper Lakes. The builder and owner

was Oliver Newberry of Detroit, elder brother of Walter L. Newberry of

subsequent Chicago fame. An innovation of the Michigan which seems never

to have been copied on other boats was the installation of two separate

engines, one on each side, and each independent of the other. The

arrangement gave increased power (the engines on early lake steamers

were frequently woefully weak) and in smooth water worked well enough.

in stormy weather, one side-wheel might be laboring deep under water,

while the other spun wildly above it, thereby jerking the vessel from

side to side, with consequences unpleasant to the passengers. The voyage

the Nowlins undertook was made on the finest ship then on the Great

Lakes. The experiences, which passengers who embarked on smaller and

less imposing ships might undergo, are illustrated in the opening pages

of Mrs. Kinzie's Wan Bun, published in the Lakeside Classics series for

1933.] then new, just ready for her second trip, lay at her wharf ready

to start the next morning. Thinking we would get a better night's rest,

at a public house, than on the steamer father sought one, but made a

poor choice. Father

had four or five hundred dollars, which were mostly silver, he thought

this would be more secure and unsuspected in mother's willow basket,

which would be thought to contain only wearing apparel for the child. We

had just got nicely installed and father gone to make preparations for

our embarkation on the "Michigan," when the lady of the house came by

mother and, as if to move it a little, lifted her basket. Then she said,

"You must have plenty of money, your basket is very heavy."

When father came, and mother told him the

liberty the lady had taken, he did not like it much, and I am sure I

felt anything but easy.

But father called for a sleeping room with

three beds, and we were shown up three flights of stairs, into a dark,

dismal room, with no window, and but one door. Mother saw us children in

bed, put the basket of silver between my little brother and me, and then

went down. The time seemed long, but finally father and mother came up.

I felt much safer then. Late in the evening a man, with a candle in one

hand, came into the room, looked at each bed sufficiently to see who was

in it. When he came to father's bed, which proved to be the last, as he

vent round, father asked him what he wanted there. He said he was

looking for an umbrella. Father said he would give him umbrella, caught

him by the sleeve of his coat; but he proved to be stronger than his

coat for he fled leaving one sleeve of a nice broadcloth coat in

father's hand. Father then put his knife over the door-latch. I began to

breathe more freely, but there was no sleep for father or mother, and

but little for me, that night.

Everything had been quiet about two hours

when we heard steps, as of two or three, coming very quietly, in their

stocking feet. Father rose, armed himself with a heavy chair and waited

to receive them.

Mother heard the door-latch, and fearing that father would kill, or be

killed, spoke, as if not wishing them to hear, and said: "John have the

pistols ready," (it will be remembered that we had pistols in place of

revolvers in those days) "and the moment they open the door shoot them."

This stratagem worked; they retired as still as possible.

In about two or three hours more, they came

again, and although father told mother to keep still, she said again:

"Be ready now and blow them down the moment they burst open the door."

Away they vent again, but came once more

just before daylight, stiller if possible than ever; father was at his

station, chair in hand, but mother was determined all should live, if

possible, so she said "They are coming again, shoot the first one that

enters!" &c., &c.

They found that we were awake and, no doubt, thought that they would

meet with a little warmer reception than they wished. Father really had

no weapons with him except the chair and knife. I said, the room had no

window, consequently, it was as dark at daylight as at midnight. The

only way we could tell when it was daylight was by the noise on the

Street. When father

went down, in the morning, he inquired for the landlord and the man that

came into his room; but the landlord and the man with one sleeve were

not to be found. Father complained to the landlady, of being disturbed,

and showed her the coat-sleeve. She said it must have been an old man,

who usually slept in that room, looking for a bed.

We went immediately to our boat. As father

was poor and wished to economize, he took steerage passage, as we had

warm clothes and plenty of bedding, he thought this the best that he

could afford. Our headquarters were on the lower deck. In a short time

steam was up, and we bade farewell to Buffalo, where we had spent a

sleepless night, and with about six-hundred passengers started on our

course. The

elements seemed to be against us. A fearful storm arose; the captain

thought it would be dangerous to proceed, and so put in below a little

island opposite Cleveland, and tied up to a pier which ran out from the

island. Here we lay for three weary days and nights, the storm

continually raging.

Finally, the captain thought he must start

out. He kept the boat as near the shore as he could with safety, and we

moved slowly until we were near the head of the lake. Then the storm

raged and the wind blew with increased fury. It seemed as if the "Prince

of the power of the air" had let loose the wind upon us. The very air

seemed freighted with woe. The sky above and the waters below were

greatly agitated. It was a dark afternoon, the clouds looked black and

angry and flew across the horizon apparently in a strife to get away

from the dreadful calamity that seemed to be coming upon Lake Erie.

We were violently tempest-tossed. Many of

the passengers despaired of getting through. Their lamentations were

piteous and all had gloomy forebodings of impending ruin. The dark,

blue, cold waves, pressed hard by the wind, rolled and tumbled our

vessel frightfully, seeming to make our fears their sport. What a

dismal, heart-rending scene! After all our efforts in trying to reach

Michigan, now I expected we must be lost. Oh how vain the expectation of

reaching our new place, in the woods! I thought we should never see it.

It looked to me as though Lake Erie would terminate our journey.

It seemed as if we were being weighed in a

great balance and that wavering and swaving up and down; balanced about

equally between hope and fear, life and death.

No one could tell which way it would turn

with us. I made up my mind, and promised if ever I reached terra-firma

never to set foot on that lake again; and I have kept my word inviolate.

I was miserably sick, as were nearly all the passengers. I tried to keep

on my feet, as much as I could; sometimes I would take hold of the

railing and gaze upon the wild terrific scene, or lean against whatever

I could find, that was stationary, near mother and the rest of the

family. Mother was calm, but I knew she had little hope that we would

ever reach land. She said, her children were all with her and we should

not be parted in death; that we should go together, and escape the

dangers and tribulations of the wilderness.

I watched the movements of the boat as much

as I could. It seemed as if the steamer could not withstand the furious

powers that were upon her. The front part of the boat would seem to

settle down—down--lower--and lower if possible than it had been before.

It looked to me, often, as though we were going to plunge

headforemost—alive, boat and all into the deep. After a while the boat

would straighten herself again and hope revive for a moment; then I

thought that our staunch boat was nobly contending with the adverse

winds and waves, for the lives of her numerous passengers. The hope of

her being able to outride the storm was all the hope I had of ever

reaching shore. I

saw the Captain on deck looking wishfully toward the land, while the

white-.caps broke fearfully on our deck. The passengers were in a

terrible state of consternation. Some said we gained a little headway;

others said we did not. The most awful terror marked nearly every face.

Some wept, some prayed, some swore and a few looked calm and resigned. I

was trying to read my fate in other faces when an English lady, who came

on the canal boat with us, and who had remained in the cabin up to this

time, rushed on deck, wringing her hands and crying at the top of her

voice, "We shall be lost! we shall be lost! oh! oh! oh! I have crossed

the Atlantic Ocean three times, and it never compared with this! We

shall be lost! oh! oh! oh!"

One horse that stood on the bow of the boat

died from the effects of the storm. Our clothes and bedding were all

drenched, and to make our condition still more perilous, the boat was

discovered to be on fire. This was kept as quiet as possible. I did not

know that it was burning, until after it was extinguished; but I saw

father, with others, carrying buckets of water. He said the boat had

been on fire and they had put it out. The staunch boat resisted the

elements; ploughed her way through and landed us safely at Detroit.

Some years after our landing at Detroit, I

saw the steamboat "Michigan" and thought of the perilous time we had on

her coming up Lake Erie. She was then an old boat, and was laid up. I

thought of the many thousand hardy pioneers she had brought across the

turbulent lake and landed safely on the shore of the territory whose

name she bore. But

where, oh where "are the six hundred!" that came on her with us? Most of

them have bid adieu to earth, and all its storms. The rest of them are

now old and no doubt scattered throughout the United States. But time or

distance cannot erase from their memory or mine the storm we shared

together on Lake Erie. |