|

INTRODUCTORY NOTICE

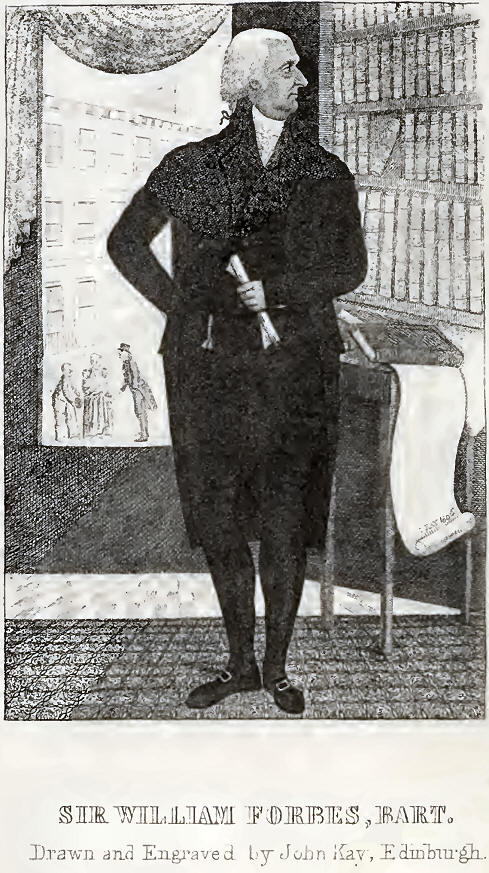

The public is here presented

with a Memoir, the genuine composition of Sir William Forbes, regarding the

history of a mercantile establishment, of which he was long the chief. The

manuscript having been accidentally shown to the editor, he saw in it so

much that was interesting, as to be induced to plead with Sir William’s

surviving friends for permission to place it before the world. It is

consequently published at the distance of fully fifty-six years from the

time when it was written, for the author appears to have closed his

narration in May 1803.

The private banking-house so long known in Scotland in connection with the

name of Sir William Forbes—merged since 1838 in the joint-stock Union Bank

of Scotland—had a somewhat complicated genealogy, reaching far back in the

last century—the century of progress in Scotland—and even faintly gleaming

through the obscurities of the one before it, when mercantile efforts and

speculations were taking their birth amidst the embers of scarcely extinct

civil wars and all kinds of private barbarisms. The genealogy is here traced

through a firm styled John Coutts & Co., of which the principal member was

John Coutts, lord-provost of Edinburgh in the years 1742 and 1743, to

Patrick Coutts, who carried on considerable merchandise at Montrose in the

reign of William III. The concern is shown as the main stock from which

branched off the eminent London banking firms of Coutts & Co., Strand, and

Herries & Co., St James’s Street.

The earlier part of the narrative exhibits banking in its original condition

as a graft upon ordinary merchandise. The goldsmith, the corn-merchant, the

commission agent, were the first who gave bills of exchange or discounted

private notes; and such were the only bankers known even in England till

near the close of the seventeenth century. The house of John Coutts & Co.

was entirely of this nature, and it had several rivals in Edinburgh. It is

curious to trace the banking part of their business as rising, from a

subordination to corn-dealing and other traffic, to be the principal, and

finally the sole business, and to learn that the banker, in consequence of

early connections, long continued to supply distant correspondents with

articles which would now be ordered from the family grocer and oilman. It

has strangely come about in our own time, that banking companies have, in

some instances, been drawn once more into what might be called merchandise,

or more properly mercantile speculation, in consequence of overgreat

advances to private traffickers. But of this vice, which we have lately seen

productive of such wide-spread ruin, there was little or no appearance

during a long middle period embraced by this Memoir. And here lies, as the

editor apprehends, one of the chief points of interest involved in the

present volume. It depicts a banking-house limiting its transactions to its

own proper sphere of business—yielding once or twice to temptations to do

otherwise, and suffering from it, till at length it put on the fixed

resolution to be a banking-house only, and neither directly nor indirectly a

mercantile speculator, and thriving accordingly. The Memoir is, however,

something more than this, for it exhibits a fine example of what prudence,

care, and diligence may achieve with small means in one of the most exalted

branches of commerce. None of the men concerned in raising up this bank were

rich, and we have details shewing us that their transactions and profits

were at first upon a very limited scale. But the business was conducted on

an appropriate scale of frugality; the simple tradesman-virtues of probity,

civility, and attention to business were sedulously cultivated. All

extravagance and needless risk were avoided. The firm was accommodated in a

floor of the President’s Stairs in the Parliament Close, and one of the

partners seems to have dwelt on ‘the premises. The whole affair thus

reminding us not a little of those modest out-of-the-way banking-houses on

the continent, which we have sometimes such difficulty in finding when we

are in search of change for a circular note. These unostentatious merits,

which we see every day raising humble traffickers to wealth and eminence,

had precisely the same effect in the case of this banking-house. The

well-descended Sir William tells the lesson with great simplicity and candour, and it is one which can never be repeated too often.

The writer of this Memoir was born in 1739, heir to a Nova Scotia baronetcy,

which his father held without any means of supporting it, beyond his

exertions as a member of the Scottish bar. Left fatherless at four years of

age, he owed much in his early days to an amiable and intelligent mother,

who contrived to maintain the style and manners of a lady on what would now

be poverty in a much humbler grade of life. His career as a banker, from an

apprenticeship entered upon at fifteen, till he became the head of an

important house, and recovered all the fortunes lost or squandered by former

generations of his family, is detailed in the work now laid before the

public, along with much of the analogous progress made by the country during

the same period. It remains to be mentioned that Sir William, in 1770,

married a daughter of Dr James Hay of Hayston in Peeblesshire, and became

the father of four sons, the eldest of whom, William, who succeeded him in

the baronetcy, and died in 1828, is addressed in this Memoir; the second,

John Hay Forbes, became a judge in the Court of Session, under the

designation of Lord Medwyn; the third, Mr George Forbes, spent his life as a

member of the banking-house; the youngest, Charles, was an officer in the

navy. Sir William, in 1805, presented to the world a life of his friend Dr

Beattie, which met a favourable reception, not merely as an elegant

narration of the biography of an eminent man, but as preserving a great

amount of the general literary history of the country which must have

otherwise perished. He did not long outlive this effort, dying of water in

the chest in November 1800, at the age of sixty-seven.

These are but the dry bones of a life distinguished in an extraordinary

degree, not merely by energy and ability in professional affairs, but by

ceaseless efforts of an enlightened character for the public good, by

inexhaustible private charity, by high taste and refinement, and the

practice of all the active virtues. One would need to have lived through the

last fifty years in Scotland, to be fully aware of the excellences of

various kinds which made people speak with such veneration of Sir William

Forbes, and maintain a faith in his modest private bank such as is now

scarcely given to the joint-stock of large copartneries. It was but

participation in a universal feeling which caused Scott to thus refer to Sir

William, in addressing one of the cantos of Marmion to the amiable banker’s

son-in-law and the poet’s friend, Mr Skene of Rubislaw:

"Scarce had lamented Forbes

paid

The tribute to his Minstrel’s shade,

The tale of friendship scarce was told,

Ere the narrator’s heart was cold—

Far may we search before we find

A heart so manly and so kind!

But not around his honoured urn

Shall friends alone and kindred mourn;

The thousand eyes his care had dried,

Pour at his name a bitter tide;

And frequent falls the grateful dew,

For benefits the world ne’er knew.

If mortal charity dare claim

The Almighty’s attributed name,

Inscribe above his mouldering clay,

“The widow’s shield, the orphan’s stay.”

Nor, though it wake thy sorrow, deem

My verse intrudes on this sad theme;

For sacred was the pen that wrote,

“Thy father’s friend forget thou not.”

And grateful title may I plead

For many a kindly word and deed,

To bring my tribute to his grave:—

’Tis little—but ’tis all I have."

And perhaps even a more

expressive testimony is given to the character of Sir William by James

Boswell, when he makes the following statement in his Tour to the Hebrides:

‘Mr Scott came to breakfast, at which I introduced to Dr Johnson and him my

friend Sir William Forbes, now of Pitsligo, a man of whom too much good

cannot be said; who, with distinguished abilities and application in his

profession of a banker, is at once a good companion and a good Christian,

which, I think, is saying enough. Yet it is but justice to record that

once, when he was in a dangerous illness, he was watched with the anxious

apprehension of a general calamity; day and night his house was beset with

affectionate inquiries, and upon his recovery, Te Dciun was the universal

chorus from the hearts of his countrymen.’

R C.

[ADDRESS OF THE AUTHOR TO HIS

SON.]

Edinburgh, 1st January 1803.

My dearest William,—

You have often heard me express an intention of writing some account of our

house of business in Edinburgh, from its first establishment by the Messrs

Coutts.

The history of a society in which I have passed the whole of my time, from

my boyish days to this present hour, during the long period of almost half a

century, cannot but be very interesting to me, especially since by means of

my connection with it, I have arrived, through the blessing of Providence,

to a degree of opulence and respectability of position, which I had very

little reason to look for on my first entrance into the world. I have often

thought that such a narrative might not be without its advantage to you, as

calculated to teach you the necessity of prudence and caution in business of

every kind, but most particularly in that of a banker, in whose possession

not only his own property, but that of hundreds of others, is at stake; and

as shewing you how, by a steady, well-concerted plan, with a strict

adherence to integrity in all your transactions, aided by civility, yet

without meanness, you can scarcely fail, by the blessing of Heaven, to

arrive at success.

From such a history, too, some general knowledge may be gained of the

progressive improvement of Scotland. For, although it is no doubt true that,

even where things remain in a good measure stationary in a country, the

business of a banking-house, the longer it exists, has a natural tendency to

increase, when it has been conducted with prudence and ability, yet it is

certainly to the rapid progress of the prosperity of this country, that the

very great extension of the business of our house during the last twenty

years must, in a great measure, be attributed. To illustrate this part of my

proposed subject, I have subjoined to my narrative a short and, I must

acknowledge, a very imperfect sketch, collected from the best authorities I

could meet with; to some of which, my situation as a man of business has

given me peculiar access. The subject is curious, and to me extremely

interesting; as I have lived in the very period when this improvement of our

native country has assumed some form, and seems still to be making daily

advances to yet greater prosperity—a reflection highly grateful to me as a

Scotsman.

To my own memory this narrative will recall many scenes on which I cannot

look back without the most heartfelt gratitude to that Almighty Being, who

has been graciously pleased to shower down upon me so large a share of

prosperity. Nor can I contemplate the many years I have spent in business,

and the number of friends of whom death has in that interval deprived me,

without the most serious reflections on the rapidity with which this life is

wearing away, and the propriety of my bending my thoughts towards another—a

subject of meditation at all times proper for a rational being; but

peculiarly so for one who has lived so long as I have done in the hurry and

tumult of a constant intercourse with the busy world—a state extremely unfavourable to sober thought and reflection.

I cannot conclude this address to you, my dearest 'William, in a better

manner than by expressing my hope that this narrative will confirm you in a

love for that profession which you probably adopted at first on my

suggestion. My wish certainly was to insure your succession to the fruits of

my labours, as far as I have had any merit in helping to raise the house to

its present flourishing state. If you continue to pay the same attention to

business that I have done (I trust I may speak it in this place without

vanity), I have no doubt that, by the blessing of Heaven on your endeavours,

you may preserve the house in credit and respectability long after I shall

have paid my debt to nature. But I never can too often nor too earnestly

inculcate that the continuance of that credit and prosperity, under

Providence, must entirely depend on yourself. If you prove yourself worthy

of the notice of your father’s friends (of which I must do you the justice

to say, I have at this moment the fairest hope), you may expect their most

cordial support, as well as a continuance of that favour and preference with

which they have so long and so steadily honoured me. But if your own

endeavours be wanting—if negligence take the place of attention to business,

and economy be abandoned for profusion of expense—you may be assured that

the concerns of the house will go speedily into decay, until at last that

decline shall terminate in absolute ruin. For, in the course of a long

experience, I can safely say that I have never known a single instance in

which relaxed management and unbounded expense did not end in total

bankruptcy.

That the providence of the Almighty may ever watch over you to shield you

from harm, is the earnest and daily prayer of,

My dearest William,

Your fond and affectionate father,

William Forbes.

Read

the book here |