|

THE period of about ten

years, from the close of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 to the great crisis

of 18 25-6, which forms the subject of the present chapter, was one of

almost profound peace. During the first year, the bitter effects of the

terrible international struggle which had convulsed the world were

severely felt in Britain. Commercial enterprise was in a state of great

prostration; provisions were scarce and dear; and the sufferings of the

labouring classes broke out in disturbances which were not always

quashed without bloodshed. In 1817, however, symptoms of improvement

manifested themselves. Commerce revived, the national industries showed

greater signs of life, and financial ventures were indulged in.

Steamboats began to ply on all the great rivers; and steam power was

applied to printing and manufactures. Foreign loans, also, became

popular, and much British capital was thus profitably employed in

ameliorating the distresses of the European nations. In 1816, the

Government issued a new silver coinage. This had become an absolute

necessity owing to the worn condition of the metallic currency. This was

so bad that it is recorded that, in some districts, the greatest

surprise was manifested at the liberality of the Government in supplying

for general currency beautifully-executed "medals" in place of the

smooth discs in circulation. Early in the following year, the gold

coinage was also renewed; and in the autumn, the Bank of England

partially resumed payment in specie. Before the death of George III., in

1820, considerable advances had been made in the national prosperity.

Some great public works—such as the Edinburgh and Glasgow Canal in

Scotland—were completed; ocean steam navigation was developed; and a

healthy amount of national industry was displayed. The two great

questions of Free Trade and Parliamentary Reform were much agitated at

this time.

The year 1820 would seem

to have been the turning point of the period, when the feverish stage

commenced. In the middle of that year a great commercial and financial

crisis occurred in Ireland, whereby private banking—which had, for the

most part, been conducted on most unsatisfactory principles—was

virtually extinguished. Some twenty banking and note-issuing firms were

swept away. This crisis did not, however, extend to Britain. There,

enterprise and industry were proceeding apace, in buoyancy and hope. In

1821, the Bank of England was permitted fully to resume specie payments;

and, during the three succeeding years, the condition of the country was

one of much prosperity, combined with which, the spirit of speculation

was largely developed. After that came the inevitable crisis.

As regards banking in

Scotland during the greater part of this period, the leading

characteristics would seem to have been, the continued development of

the large banks, and the withdrawal or failure of purely local

establishments. Previous to 1825, only two new firms commenced business.

The first of these was the Exchange and Deposit Bank of John Maberly &

Co., with offices at Aberdeen, Montrose, Dundee, Edinburgh, and Glasgow.

They were properly an English linen manufacturing firm, and in 1818 they

established themselves as bankers in Scotland, with the object of

profiting by the high rate of exchange on London. This entrance on the

Scottish field was by no means relished by the native bankers; but it is

probable that the public profited by it. This will be understood when it

is remembered that the usual par of exchange was 40 to 50 days; whereas

Maberly commenced with 20 days, and latterly reduced the period to 10

days. The result showed that the intrusionists overreached themselves in

adopting a scale which has only in recent years been naturally attained

to; but there can be little doubt that their opponents had erred on the

side of their own interest. After a career of fourteen years as bankers,

Maberly & Co. succumbed in 1832; but it does not appear whether their

failure is to be attributed to the banking or to the manufacturing

business. The liquidation was conducted under an English fiat of

bankruptcy, the debts in both departments of the business amounting to

£149,082, on which a dividend of 4s. 5d. per £ was paid. As the assets

are stated to have realised £76,669, it would seem that the expenses of

liquidation were very heavy.

The second bank to which

we have referred was the firm of Hay & Ogilvie, who commenced business

in Lerwick in 1821, under the designation of the Shetland Bank. They

were also engaged in trade, which part of their business was, no doubt,

previously established. They appear to have ceased issuing their own

notes in 1827; but for what reason is not stated. They continued for

twenty years, when they made a bad failure. One of the partners, John

Ogilvy (the name is thus printed in the notice, although differing from

the spelling in the official style of the firm), died in 1829; and the

failure, according to one authority, [Boase, 2nd ed., p. 364.] occurred

in 1830, with debts, both as merchants and bankers, amounting to

£60,000, on which a dividend of 6s. per £ was paid. The date is

otherwise given [Somers, p. 107] as 1842, the liabilities as £140,000,

and the dividend in sequestration as 5s. per £, with the prospect of a

little more. Perhaps they resumed business, after a composition, in

1830. From this time to the closing year of the period, bank extension

consisted entirely in the opening of branches throughout the country.

The Commercial Bank and the British Linen Company displayed the greatest

amount of activity in this respect.

A marked feature of this

period was the disappearance of a considerable number of banks—the exits

being pretty well spread over the ten years. In 1816, the Falkirk Union

Bank, with liabilities to the amount of £60,000, was sequestrated. The

number of partners was only eight. Malachi Malagrowther states that they

met their engagements without much loss to their creditors; but it is

probable he had not asked the latter for their opinion, seeing the total

dividend did not exceed 10s. per £. However, it was a small concern. In

1820 a little known establishment, called the Glasgow Commercial Bank,

withdrew from business. Towards the close of the next year the firm of

Sir William Douglas, Bart., & Co., carrying on business at

Castle-Douglas, under the style of the Galloway Banking Company, was

also wound up. It had existed for fifteen years. It may be presumed that

its liabilities were met in full. At this time, also, the Kilmarnock

Banking Company, who started early in the century, merged their business

in that of Hunters & Co., Ayr.

In the following year

(1822) a very unfortunate failure occurred. The East Lothian Banking

Company had been formed at Dunbar in 1810, with a capital of £80,000, in

400 shares, held by twenty-seven partners. It would seem that the bank

never did well. This was principally owing to the disreputable conduct

of the cashier (or manager), William Borthwick, who, after involving the

bank in much bad business, absconded with £21,000, on 10th April 1822.

Messrs. Forbes & Co., of Edinburgh, advanced £100,000 to assist the

liquidation, pending the realisation of the assets and a call of £250

per share. The liabilities amounted to £129,000, and the assets to

£63,000; but the partners paid in full. In connection with this affair

there is a rather mythical-looking account of a design on the part of

Borthwick to kidnap one of the directors and the law agent—who were

probably of too inquiring a disposition for his taste—in order to

further his private designs. According to Borthwick's written

directions, which were found among his papers, they were to be inveigled

to a specified place, seized, gagged, and put into empty puncheons with

air-holes. They were then to be taken to Dunbar and shipped (presumably

as Scotch ale) on board a vessel belonging to Borthwick's brother, which

was about to sail for Dantzic. Thereafter they were to be conducted to a

desolate part of Prussia and confined eight or nine months "without

change of clothes or shaving materials." The conspirator concludes (what

was, doubtless, a day-dream with which he gratified his spleen) thus: "I

will venture to affirm that at the expiry of that time they will have

repented most sincerely of their conduct." [Banking in Glasgow.] In 1824

the Edinburgh firm of John Wardrop & Co. disappeared from the list of

bankers.

The year 1825 is notable

for the establishment of four new banks, all of which were successful.

One of these was the Aberdeen Town and County Banking Company, which is

one of only three provincial banks surviving from the multitude which

have been started. Let us hope that no amount of charming on the part of

the large banks will induce these establishments to forego their

independence. The roll of banks in Scotland is small enough; it can

hardly be for the public advantage to have competition further narrowed;

and the advantage to the shareholders, so long as their business is

prosperous, of amalgamation, is probably not sufficient to

counterbalance the chances they would forego of development into

national banks. The Aberdeen Town and County Bank (now the Town and

County Bank, Limited) started with a capital of £150,000, held by 470

partners. Another bank established in this year was the Arbroath Banking

Company, with a capital of £100,000 subscribed, and of £40,000 paid. It

amalgamated with the Commercial Bank of Scotland in 1844. A third was

the Dundee Commercial Bank (the second of that name), with a capital of

£50,000. It retired in 1838, in favour of a newly-organised company—the

Eastern Bank of Scotland—which was designed to carry on a more extended

business. Thus euphemistically; but one who was well able to speak on

the subject thus describes the event: "The mystery of this proceeding

was revealed in the course of winding up the affairs of the former bank,

when the partners came to find that not only had its whole capital been

lost, but about half as much more, which, less the premium of £20,000

received from the Eastern Bank for the goodwill of the business, they

had to liquidate. For this purpose £40 per share was called up; but £13:

10s. per share of this was returned subsequently. [Boase.]"

The fourth was the now

well known and powerful establishment, the National Bank of Scotland.

From the outset, it appears to have been designed on a large scale.

Indeed, it was the result of the combination of no fewer than three

distinct banking companies projected in 1824. The first of these seems

to have been the Scottish Union Commercial Banking Company; but it was

speedily followed by the Scottish Union Banking Company, and the

National Bank of Scotland, the prospectuses of all three being before

the public at the same time. The advertisements of all of them state

that the subscriptions were rapidly filling up; but it seems to have

become evident, even to the enthusiastic promoters, that such an

accession to the number of Edinburgh banks was unadvisable. The Scottish

Union and the National made what they termed "a treaty of union,"

whereby they were to unite their interests and divide the prospective

appointments to their mutual advantage, under the designation of the

Scottish National Banking Company. They then held out the olive branch

to the Scottish Union Commercial; but their advances were not

reciprocated.

However, the united

companies were not to be so easily baffled in their design of preventing

rivalry. Finding they could not win the promoters to their side, they

made a seductive attempt on the subscribers. On 1st January 1825, the

united companies published a long advertisement, in which they reflected

warmly on the "insidious" conduct of their rivals, and threatened that,

if the Union Commercial Company would not join them, they would

advertise their readiness to receive individual subscribers to that

company into their concern. Whether as the result of this threat, or

from the prevalence of reasonable counsels, the two parties came to an

agreement within a few days, and announced the "union of all of the new

banking companies of Edinburgh" as the Scottish National Banking

Company. As the subscription lists were closed on 8th January, there

seems to have been no difficulty in completing them. Further delays

occurred, however, and it was not until 21st March that the company got

finally started as the National Bank of Scotland. The nominal capital

was £5,000,000 (now fully subscribed) in £10 shares. At first only

£500,000 of the capital was issued.

The bank seems to have at

once commenced a branch system, by the establishment of offices in nine

towns, seemingly rather selected from their geographical positions as

embracing the whole country, than from their business importance. In

1833 they had 24 branches; and a continual increase has now brought the

number up to 115. In 1831 the company obtained a Royal charter of

incorporation, granted under the pernicious principle of unlimited

liability, which at that time commended itself to statesmen as superior

to the ancient principle of limitation, which is now again held, under

the light of terrible experience, to be the proper constitution of

corporations.

Towards the end of 1825,

another attempt was made in Edinburgh to organise a new bank. [Scotsman

newspaper, 26th November 1825.] It was to be on a different footing from

the National Bank, as it was not intended to extend its operations

outside the metropolis, but to conduct it as the Glasgow and other local

banks were then managed. But the events of the closing months of the

year put an end to the project.

The earlier part of 1825

witnessed the climax of the speculating spirit which had been working

with ever-increasing excitement since 1820. The opening of the Spanish

South-American Colonies, by the achievement of their independence, to

British enterprise, had stimulated industry, and had occasioned a mania

for loans to the new States. These loans are estimated at fifteen

millions. At the same time, bubble companies were rampant, and gambling

in their shares was excessive. The economic heresy, called the

mercantile system—which proceeded on the assumption that the wealth of a

nation was coordinate with its command of the precious metals—exercised

an evil influence at this time. It was thought that the boundless

natural stores of gold and silver in the Spanish colonies had only to be

tapped by British commerce to secure the wealth of the fortunate

adventurers. Lord Lauderdale stated that the schemes subscribed for

amounted to two hundred million pounds. From a statement made at the

time, it would seem that "the accumulation of capital which has been

progressively going on, since the conclusion of the last peace, and the

difficulty of now investing money to advantage, has given rise within

these few months to the formation of numerous trading companies

throughout the country, with capitals of from £25,000 to half-a-million.

In Edinburgh we have a new Banking Company, a new Insurance Company, a

Wine Company, a Porter Brewery Company, an Equitable Loan Company, a

Whale-fishing Company, Glass and Iron Manufacturing Companies,

Cotton-Spinning Companies, and a variety of others which it would be

tedious to enumerate. No sooner was the prospectus of a new scheme laid

before the public than capitalists and speculatists ran eagerly and

filled up the shares; and it was no uncommon thing to see these shares,

in the course of a day or two, selling at a high premium. Much money was

lost and won upon this kind of lottery." [1 Scots Magazine, March 1825.

The bank alluded to above is, no doubt, the National Bank of Scotland.

The insurance company might be the Scottish Union (now Scottish Union

and National) Fire and Life, but is, more probably, the Standard Life ;

but the Thistle, Equitable, and Commercial Marine were also local

insurance projects of the time. The Wine Company of Scotland continued

to exist until 1853, when the business was transferred to a private firm

; and the pawnbroking establishment spoken of occupies a respectable

place, at the present time, on the local share list. Other companies

alluded to are the Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Alloa Glass Company, Shotts

Iron Company, Scottish Brewing Company, Scottish Wool Stapling Company,

Waterloo Hotel Company, and Caledonian Dairy Company.] Of course, in

London speculation was on a still greater scale. "It is estimated that

the different new schemes on foot in London amount to 114, and the

capitals to be more than £105,000,000."

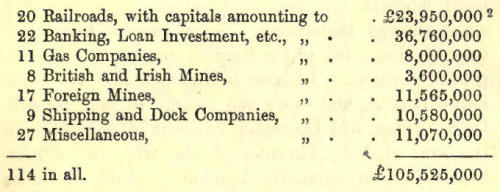

These are enumerated as

follows, viz.:—

2 This item is given as

£13,950,000 in the original, but is, doubtless, a misprint.

The turn of the tide took

place in the month of April. Prices of stocks and shares began to

decline, calls were made on shareholders, the Bank of England bullion

was ebbing away, and want of confidence began to manifest itself. In the

three months, April, May, and June, nearly £3,000,000 of bullion were

exported, mostly to the Continent, and it was estimated that the demands

for exportation had reduced the stock of bullion in the Bank from

£12,000,000, on 1st January 1824, to about £4,000,000 at the beginning

of August 1825. [Scotsman newspaper, 3rd August 1825.] It was not,

however, until later in the year that palpable evidences of a crisis

showed themselves. Some private firms succumbed, then a few of the

English country bankers suspended payment. Distrust became general; the

panic seized London, and every one sought to save himself. On Saturday,

3rd December, rumours of difficulties in the firm of Pole, Thornton &

Co., who, in addition to having an extensive London banking business,

were agents for a large number of provincial and Scottish banks, gave

point to the excitement. The Bank of England advanced £300,000 to the

firm, and the catastrophe was deferred.

But on Monday the 12th,

no longer able to stand the strain on their resources, Pole, Thornton &

Co. stopped payment. Then the panic rose to a crisis. Stocks were

unsaleable, and even Government Securities were not looked at. Every one

who had coin hoarded it. For two days-12th and 13th December—the

financial and commercial world was in a state of paralysis. On the 14th,

the Bank of England came to the front. The directors gave assistance

right and left to all who produced fair security. The crisis passed, and

business men breathed more freely. The dread of universal ruin was past,

and they began to estimate the resources of their neighbours with some

degree of calmness. £1 notes of the Bank of England were sent into the

country, to supply the want of specie; and affairs gradually assumed a

quieter phase. The results of the crisis had, however, been very

serious. Many bankruptcies had occurred, including some London and many

provincial banks. It would appear, however, from the estimates of

liabilities and assets, that the English provincial banks who failed had

not been in so bad a condition as might have been expected. Subsequent

investigation showed, moreover, that wherever the error lay, the note

issues had comparatively little to do with their position.

In Scotland, as usual,

the crisis had comparatively little immediate effect, although the

subsequent depression was severe and lasting, as was strikingly

indicated by the large amount of heritable property which was thrown on

the market within a few months after the crisis. For the most part,

business went on as before. The .Edinburgh banks seem to have

experienced no discomfort. An exception must, however, be made in regard

to Glasgow and the West of Scotland. There, if panic did not actually

break out, much uneasiness was felt in commercial circles. Contemporary

accounts represent the state of trade and manufactures as very bad.

Several of the cotton mills were put on halftime, and others were

verging on the same condition; while the country weavers were in vain

seeking employment. The Bank of England sent a commission to Scotland,

under which a sum of £300,000 was to be advanced in Glasgow. It was

believed at the time, that the applications for assistance from this

body were very few; and the action of the bank was, in some quarters,

regarded somewhat ungraciously, with true Glasgow independence. The

banks were not affected; indeed, it is stated that they, and especially

the Royal Bank branch, under the management of Mr. J. Thomson, were very

efficacious in allaying the threatened danger. But, although banking in

Scotland, as a whole, escaped very easily, it was not unscathed. Three

banks succumbed. One of these was the Caithness Banking Company of Wick,

whose business was taken over by the Commercial Bank. Another was the

Stirling Banking Company, with liabilities exceeding a quarter of a

million sterling; but, although it was sequestrated, its eight partners

paid in full. The worst case was that of the Fife Banking Company. It

had a capital of £30,000, and might have done well. It was, however,

grossly mismanaged, got into difficulties during this crisis, and

stopped payment on 15th December 1825. It struggled on, however, under

rearrangements, and did not finally close until 21st May 1829. Its

affairs were not settled until 1850, owing largely to litigation carried

to the House of Lords. The loss to the shareholders was enormous.

Fourteen outstanding shareholders paid £5500 per share beyond the

original amount. The liabilities were met in full. |