|

A Relic of 1858 - Caledonian

Festival in 1860 - First English Cricket Eleven Routed - "A Little Pig in

a Narrow Gate" - From Archery to Shinty - Old Programme Survives -

Distinguished office-bearers.

IF the Caledonians of

Melbourne celebrated St Andrew's Day in 1858 (and it is reasonable to

suppose that they did), the fact seems to have escaped the notice of

newspapers of the period. Nor have we any domestic records, such as

minute-books, to shed light on the initial activities of the Society.

Only one tangible relic of

Scottish enterprise in the Melbourne of '58 is in hand today. Strangely

enough, although this object was produced in Melbourne it came to us, and

that only recently, from Scotland. The medium was John Keith of Ballarat,

who received it from the Burns Federation of Glasgow.

The relic in question, a

programme printed on silk, relates to "Mr Black's Entertainment of

Scottish Song" (subtitled "A Nicht Wi' Burns"), which was held in the

Mechanics' Institute, Melbourne, on 13th October 1858. The function,

although under the patronage of His Excellency Sir Henry Barkly, does not

appear to have been promoted by the Caledonian Society, but, at least, the

well-preserved old programme is an interesting link with Melbourne's

childhood.

A couple of years later

(1st December 1860 ) the Melbourne Herald found itself moved to

congratulate the Celedonian Society on "the great success of their second

annual festival". That means, obviously, that the first festival was held

in '59, and yet no reports of the function can be found.

Anyway, there can be no

doubt about the impressive nature of the "Grand Caledonian Gathering" of

1860, which extended over Friday 30th November and Saturday 1st December.

It was held-more or less appropriately, cynics may say-at the Zoological

Gardens, and its programme during the two days ranged through music,

dancing, games, archery, and rifle-shooting, with a draughts tournament

adding to the variety.

"The Caledonian fete", says

the Herald on 1st December, "was in almost everybody's mouth". It adds

that so heavy was pressure on the Melbourne and Suburban Railways that

"there was no room for crinoline, and the ladies had to compress their

fabrics into as small a compass as possible".

Railway employees had

rarely known such heavy patronage. "One indefatigable ticket porter," the

Herald reveals, "was so concentrative as to manage to stuff a school of

young ladies, numbering in all some five-and-twenty, into a carriage

already full of adults."

The attendance during the

two days numbered about 20,000, a fact which caused the Governor (Sir

Henry Barkly ) to congratulate the Secretary (John Campbell) and other

officials of the Caledonian Society.

Meanwhile, a slightly

peevish note was struck by the Argus. In a leading article dealing with St

Andrew's Day the journal set out to curb over-enthusiastic Caledonians. It

did so by remarking that the bagpipes affected Scots in the same way as

"the beating of a tom-tom charms the ear of an Arab", and, to emphasize

its aloofness, it added that the fact that other people were not so

affected was "not a reason for inconsolable sorrow".

The Caledonians, of course,

treated that uncivilized leader-writer with lofty disdain!

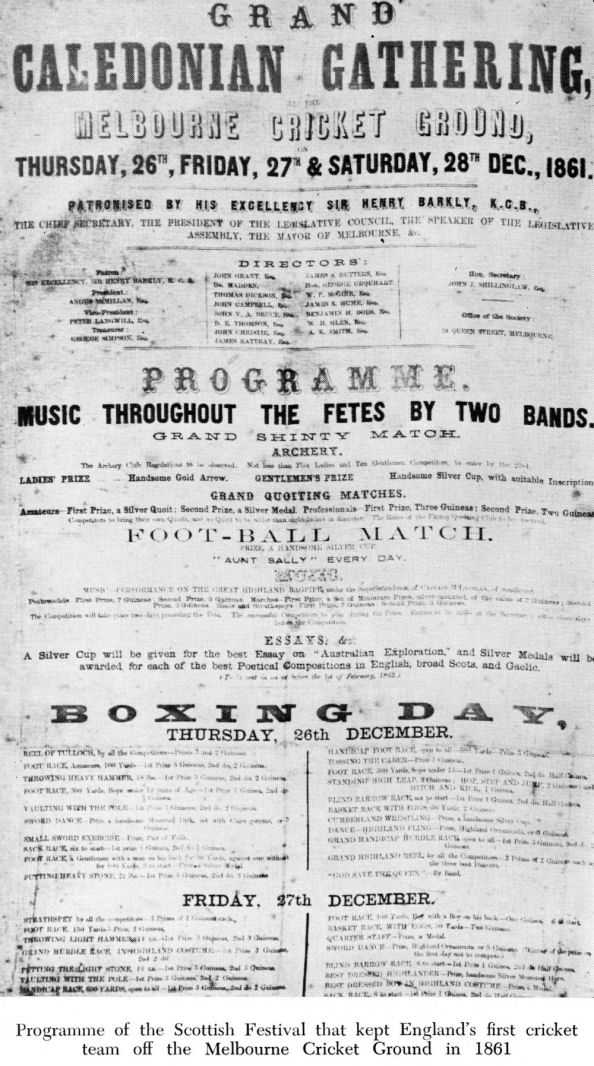

Encouraged by the success

of 1860, the Society went one better in the following year by conducting a

festival extending over three days (26th to 28th December), and this time

the site was the Melbourne Cricket Ground. What did it matter that the

first "All England" team, led by H. H. Stephenson, was in town at the

time, and was due to play its first match on the M.C.G. on 1st January! A

small development of that kind could not be allowed to affect the welfare

of a Scottish demonstration. Let the "foreigners", with their bats and

balls, go to St Kilda or Richmond for practice! Bannockburn for ever!

Anyway, the big catering

firm of Spiers and Pond, which had sponsored the visit of Stephenson's

team, was also caterer for the Caledonian gathering, and so had a foot in

each camp. It, therefore, cared for the 20,000 or so visitors to the

Scottish festival from 26th to 28th December, and then catered at

Australia's first international cricket match-the English Eleven v. a

Victorian Eighteen-on the same ground two days later, 1st January 1862.

All newspapers of the time,

although much occupied with the tragedy of the Burke and Wills Expedition,

gave lengthy reports of the Caledonian festival, incidentally

congratulating the Society on the large attendance each day and on the

fact-which seems to have occasioned some surprise that the ground was left

undamaged.

As in 1860, the only

spectre at the feast was the leader-writer of the Argus, who seems to have

had a personal grouch against bagpipes.

After proclaiming that

Scottish national games were surely amongst the most singular of all

festival celebrations", the critic went on to say: "Southrons, to whom the

sound of a bagpipe is like the squealing of a little pig in a narrow gate,

may be permitted on these occasions to indulge in wonder at such fearsome

mysteries." Other comments in kind followed. Then, apparently waxing

benevolent, the writer expressed a high opinion of the "gravity, sobriety,

and discretion of our Scotch neighbours in all matters of, or pertaining

to, the business of the world" - which remark, when you come to examine

it, seems even more "loaded" than the one about the little pig in a narrow

gate!

As in 1860, too, the

programme of '61 included music, dancing, rifle-shooting, sword play,

archery, caber-tossing, putting the stone, jumping, and foot-racing, with

additions in the form of wrestling ("after the Cumberland and Westmorland

fashion"), a football match, a "grand quoiting match", and a "grand shinty

match". Also, the enterprising promoters offered a silver cup for the best

essay on Australian Exploration and three silver medals for "the best

poetical compositions in English, broad Scots, and Gaelic".

What more varied diet could

any pleasure-seeker of the 1860's have desired?

Unfortunately, the football

match (presumably Australian Rules, which appears to have originated in

Melbourne in 1858), fell through because the ground was found to be too

small; the archery contests failed through lack of sufficient competitors

(five ladies and ten gentlemen had been stipulated), and, for some

unspecified reason, the "grand shinty match" also fell by the wayside.

Other events, however, went through satisfactorily, and the wrestling in

particular "excited the warmest approbation".

Incidentally, favourable

comment was aroused by "the elegance and richness of the ladies' toilets",

but there was some criticism of the fact that only about twenty men

appeared in Highland costume, whereas in former years the number so

dressed had been approximately one hundred.

On the whole, the

three-days' gathering was considered by all newspapers to have been very

successful, so much so that the Argus was moved to say, "No small thanks

are due to the Caledonian Society of Melbourne for what they have just

accomplished."

(It should be noted, by the

way, that the newspaper's reference to the "Caledonian Society of

Melbourne" indicates that even at that early stage the modern title was

sometimes used. Actually, of course, the correct title then was

"Caledonian Society of Victoria").

Allowing itself a final

flourish, the Argus concluded its description of the festival on this

dramatic note: "The two bands thundered out `God Save the Queen', and the

Caledonian gathering of 1861 belonged to the past." As a fact, though, the

celebrations did not end then; they extended a few days later into a

"Grand Caledonian Ball", and by that time, no doubt, Melbourne was more or

less mesmerized by the sight of kilts and the sound of pipes.

Certainly it was a bold

enterprise, on the part of a young Society, to take charge of the town in

such a hearty fashion; and that fact may explain why the officers,

desiring to commemorate their achievement, had one of the calico-printed

programmes framed and hung. That programme remains with the Royal

Caledonian Society today. It is the sole "official" relic we possess of

the period before the re-birth of the Society in 1884.

Included on the programme

are the names of the officers of the day. His Excellency Sir Henry Barkly

was still Patron, but other officials had changed considerably in the

three years or so since the Society was formed. Now Angus McMillan was the

President, Peter Langwill Vice-President, George Simpson Treasurer, and J.

J. Shillinglaw Hon. Secretary. Similarly, there were many "new" names on

the list of Directors.

All of the men holding

office were citizens of standing and in some instances their names belong

to history.

"Mr President" was, of

course, the Scot who, coming to this country in 1838 (at the age of 27)

became in 1839-40 the discoverer of Gippsland, and later was the first

representative of portion of that area in the Victorian Legislative

Assembly. It is recorded in Serle's Dictionary of Australian Biography

that he "took particular pride in his election as president of the

Caledonian Society of Victoria".

As for the Secretary, John

Joseph Shillinglaw, he was a man of 31 who had then (1861) been only nine

years in Australia, and had already occupied several important positions,

including that of shipping-master of the Port of Melbourne. Later he was

to become Editor of the Colonial Monthly Magazine and to distinguish

himself by carrying out important historical research.

A third Caledonian officer

of the time whose name lives on was John Van Agnew Bruce, one of the

Directors. A native of Edinburgh, Bruce was, in the words of the Melbourne

Herald, "one of the many 'puir laddies' who through the excellent school

system of Scotland had been able to fashion out a remarkable career".

Having little money on reaching Melbourne, about 1854, within a few years

he was able to obtain the contract for the building of the railway from

Melbourne to Sandhurst (Bendigo), the price being £3,356,937 2s. 2d.

Need we wonder that, with

men of such enterprise at the head of affairs, the Caledonian Society

monopolized the Melbourne Cricket Ground for three days in 1861, and,

while so doing, caused visiting English cricketers to go to Richmond for

their practice?

All the same-while paying

due tribute to the spirit of those men of old-we may fairly doubt if they

would have similar success were they alive today. These being degenerate

days, it is somewhat difficult to imagine Scots being allowed now to

arrange for cavalry exercises, tossing the caber, and putting the stone

(to say nothing of a "grand shinty match"), on the Melbourne Cricket

Ground on the eve of the appearance of an English Eleven! |