THE SYSTEM OF EDUCATION in the former

days, if system it may be called, was very different from that of

the present day. There was little machinery employed in carrying it

on. Probably in new settlements it was a voluntary organization,

without trustees, school-house or licensed teacher. Schools were

private concerns supported by individuals who had children to be

educated. The school was held in a private house and taught in

winter by men, in some cases of fair ability and scholarship, but

more commonly by such as had failed in almost everything else, and

in the summer season by women. Frequently, a man having a family was

employed for the whole year, taking farm produce in payment for his

salary, and not being "passing rich with forty pounds a year," he

supplemented his stipend by gardening or small farming. There were

very few who made teaching a vocation or permanent business, and

there was no such thing as a trained teacher or a Normal School.

Teaching was a resort—too often a last resort—to which one betook

himself when he had failed at everything else.

For many years young

men who desired higher education and professional training were

accustomed to go to the Universities of the United States and Great

Britain. Preparatory work for these institutions was generally done

under the supervision of private instructors, chiefly clergymen who

were graduates of universities in the old country. Candidates for

law and medicine took a preparatory course under practitioners of

their chosen profession.

Towards the end of

the eighteenth century and in the early years of the nineteenth a

movement began for the establishing of high schools and colleges in

Nova Scotia. Kings College, organized in 1789, in Windsor, was the

first institution of the kind in the Province. Through

ecclesiastical restrictions, such as withholding diplomas from

graduates who refused signature to the doctrines of the Anglican

church, by which body it was controlled, it failed to meet the needs

of the country and to become a provincial institution. At this time

not over one-fourth of the population were connected with that

church.

The lack of

facilities for the education of a native ministry was felt seriously

by the dissenting churches and led to the founding of Pictou

Academy. It is said that some one—a man of sound judgment he must

have been—having been asked to give the essential elements of an

efficient college, replied,—"A big log with Mark Hopkins seated on

one end and a live student on the other," or to that effect. Pictou

Academy fittingly illustrated this definition. It got the cold

shoulder, however, from the powers that barred the doors of King's

College against Dissenters, and so it struggled to its feet under

adverse conditions. It had not even a log that it could call its

own. Its classes met in private houses; its Faculty comprised a

single professor, Thomas McCulloch, D.D., but he was a whole man and

all there. And while the Government of Nova Scotia refused to grant

the institution degree-conferring power, the graduates had no

difficulty on examination in taking degrees from Glasgow University.

The institution became eminently useful, not only in the special

sphere for which it was established, but also in the preparation of

many for other professions, who attained distinction in their lines

of public service.

Somewhat similar work

was done in the western part of the Province by Rev. William

Somerville in his seminary at first established in Lower Horton and

later in West Cornwallis. This institution was recognized by a

provincial grant from the School Commissioners of King's County down

to the time when the Free Schools Act came into operation. Strange

to say this very Act took away the power of the commissioners to

continue the grant to this distinguished educator unless he

submitted to examination for license by men far below him in

scholarship and ability.

Educational machinery

came in at the time of legislative aid to common schools early in

the nineteenth century. The counties were divided into school

sections or districts as they were then called. Each county had its

Board of School Commissioners having the power of licensing teachers

and the distribution of government grants with a general oversight

of the public schools. The section or school district was authorized

to elect a Board of Trustees whose duty it was to solicit

subscriptions for the support of the school and employ a teacher.

For many years the functions of the Trustees were little more than

nominal, consisting chiefly in signing the teacher's report of work

done during the term, by which they certified to the correctness of

what they knew little about. According to the custom of the time a

teacher's license was obtained from any two Commissioners, or from

such other examiners as the Board chose to appoint, stating that

they were satisfied as to the qualifications of the candidates.

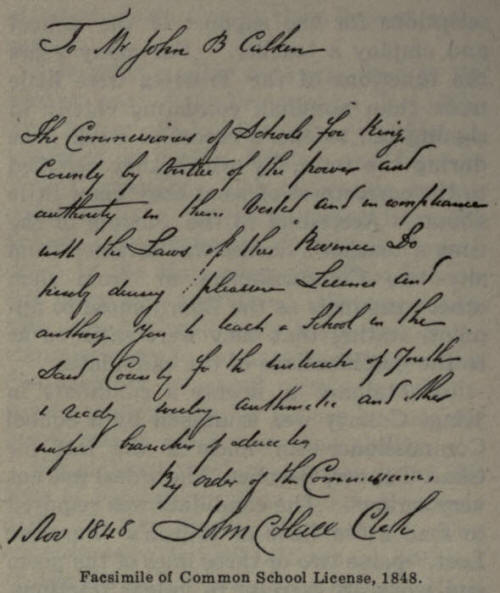

In obtaining a

license a candidate in Kings County was examined by a School

Commissioner—an uncle of the late Sir Chas. Tupper, Baronet. The

ordeal was not very serious. The candidate was required to read a

few lines of Milton's "Paradise Lost," parse two or three lines of

the poem and work an exercise in vulgar fractions. Having done the

exercises to the satisfaction of the Commissioner he readily

obtained endorsement of the Certificate by another Commissioner

without further examination. The following is a copy of a Common

School License issued in the year 1848.

It was seldom that

the Trustees stood in any responsible capacity between the teacher

and the people. The contract was made directly between the Teacher

and the "proprietors", that is the parents who sent their children

to school. The teacher bound himself to teach a "regular" school for

a specified term, giving instruction according to the best of his

abilities in certain branches, usually limited to reading, writing

and arithmetic—sometimes adding geography and English Grammar. It

bound the signatory patrons to provide suitable school room, fuel,

books, and board for the teacher with the further item of paying the

Teacher for work done. Sometimes the amount to be paid was a fixed

salary to be divided among the patrons according to the number of

days attended by their children; often it was a fixed amount for

every week's attendance —nine pence or perhaps a shilling a week.

The teacher was sure of his board and fairly sure of the Government

allowance at the end of the half year—as for anything more he ran

some risk. Then, as to board, he was a visitor at the homes of the

children—he "boarded around," measuring out the time to each of his

many homes according to the number of pupils he had in it. Of course

he was not scrupulously exact in this matter. If he fell in with a

good place, he showed his appreciation by prolonging his visit, with

corresponding lessening of time in places where the fare was less

generous. Whatever might be urged against this custom of boarding

around, this could be said in its favor—it was relieved from

monotony, and the teacher had an opportunity of becoming acquainted

with the homes of his pupils. Nevertheless, with all its advantages,

a teacher was known to object to the custom, especially as he

desired to board where he could have a private room for undisturbed

study. His objection was thought to be remarkable and the reason

given most unreasonable. The people supposed that they were

employing a teacher, not a student. The subscription paper was

circulated by a trustee, some interested parent, or by the teacher.

At the close of the term similar means of collecting the salary was

adopted.

In these old times

school books were neither large nor numerous, nor were they

expensive. Indeed, at one time within the writer's memory, the whole

school course was comprised in a single text-book and that a very

slender one. This ideal text-book begins with the alphabet—the A B

C's, as it was called, followed by the a b abs, the b a bas, and the

b l a blas. Then there were simple words of one syllable in which

every letter was pronounced. In a more advanced stage these words

were combined into sentences. Moving on, the pupil soon found

himself in deeper water—words of two, three, four, or more

syllables. Then there were words spelled differently with the same

pronunciation as air, one of the elements; ere, before; heir, one

who inherits. The lessons in reading included selections from the

Book of Proverbs, Esop's Fables illustrated and Natural History.

Lessons were given on Geography, English Grammar, Arithmetic and

abbreviations in writing, and Latin words and phrases in common use.

Nor was religious education overlooked. This little book contained

"The Church Catechism," "Watts's Catechism," Prayers for use in

school and for home use morning and night, "Grace before Meat" and

"Grace after Meat." All these and more were in this book at the cost

of one shilling or about twenty-five cents Canadian Currency. The

book was entitled "A New Guide to the English Tongue" by Thomas

Dilworth, School-master.

The school-room was

fitted up in most economic fashion. On one side was a large open

fireplace, and in a corner near by was a desk or a table at which

sat the teacher often writing copies, or making goose-quill pens—the

steel pen is a modern invention. While thus engaged he heard a class

of young children read. Around three sides of the room were the

writing tables, consisting of a board about four inches in breadth,

extending horizontally from the wall as a shelf for ink-wells, pens

and other things. To the edge of this shelf was attached a slanting

board about twenty inches wide for a writing table. Originally it

was fairly smooth, but in course of time its surface had become much

changed, showing various designs in wood-carving with jacknives by

young artists. On the south side, opposite a window, one might find

a deep cutting for use rather than ornament—a sun dial to indicate

the noon time.

The seats in those

days were made of slabs supported by legs made of stakes driven into

auger holes on the under side. They had no support for the back, and

their legs were long enough for a full grown man, adapted to the

convenience of Sunday meetings and singing schools in week day

evenings, so that the children's feet did not reach the floor. When

writing, the pupils faced the wall; at other times inward toward the

master.

An amusing feature

was the spelling exercise to which the last twenty minutes of the

day were devoted. At first came the preparation of the lesson. The

pupils seated on the high benches and facing inwards studied aloud

and with no uncertain sound. As they pronounced each letter and

syllable and word after this fashion—v o vo, l u n lun, volun, ta ta,

volunta, r i ri, voluntari, l y ly, voluntarily—they swayed to and

fro, keeping time in their bodily movements above the seat and below

the seat with the rhythm of their voice, gathering up the syllables

as they went along, and finally pronouncing the whole word. At the

close of the preparation all stood in line around the room while the

teacher heard the lesson. There was "going up and down," which

excited much emulation, gravitating each way from about the middle

of the line, the one at the foot seeming to be as proud of his

position as was he at the head. |