MANY things are better than they appear

at first sight. Have you not found it so? Even a hen finds it pays

to scratch and look beneath the surface. Often she gets a worm for

her pains,—and sometimes a kernel of corn. You will see this

exemplified in many of the old nursery stories such as "Jack and the

Bean Stalk," "Little Jack Horner," "Jack the Giant Killer," and the

subject before us—"Jack and Jill." We all remember the fun we got

out of them in our younger days. We then thought that there was

nothing in them but nonsense. Look farther down into the heart of

them and see if you do not find richer treasure.

Did you ever notice

that every one of these heroes is a Jack. Look up this word in an

unabridged dictionary, such as The Century, which I hope you have,

and note how many useful things are called Jack something, as

jack-knife, jack-plane, jack-screw, jack-smith, boot-jack, and

scores of others. Note that they are all made for doing things—for

important service. The world could not get along without them. From

its associated content the word jack would suit as well for a

patriot's motto as the historic Ich Dien in the Prince of Wales's

coat of arms. But I must not wander about in this fashion or I shall

never get there. I have set out to tell you, my reader, what I have

discovered in Jack and Jill—the poem I mean.

Nobody knows when

this poem was written, by whom, or where. Like the story of the

Noachian Deluge its variant tradition is almost world wide. It is

told in every civilized language, and it goes back beyond the dawn

of veritable history into the shadowy past where truth and fiction

are inextricably tangled together. In the Northlands the peasants

have a legend that a crusty old tyrant compelled the heroes that

figure in the poem to fetch water from a distant well until they

would have died from exhaustion had not the man in the moon snatched

them away to live with him. And to this day these simple minded

people believe, so it is said, that Jack and Jill may be seen on the

face of the moon.

I have called this

piece of early composition a poem. It is difficult to give a very

satisfactory definition of poetry, and I shall not now undertake the

task. Suffice it to say that some of its elements are rhythm, the

choice and arrangement of such words as are adapted to the awakening

of emotion, due recurrence of accented and unaccented syllables, and

often, though not always, combined with definitely measured lines

and rhyme or similarity of sound at the end of the lines. Of the

three great kinds of poetry, dramatic, epic and lyric, I do not

hesitate to place the poem "Jack and Jill" in the class epic, it

being in form of a narrative, the author telling the story in his

own words.

Yes, Jack and Jill is

a great epic. True, when measured by lines or by words, it falls far

behind others of its class; but in thought and style it transcends

them all. Allow your mind to dwell on the picture so vividly

portrayed by a few skilful touches, and idea is superadded to idea

until one is simply amazed at its content. So far reaching and ever

widening is the conception that the mind fairly loses itself in the

vast field spread out in panoramic distinctness and beauty. Its

magnitude consists rather in its implications than in multitude of

words;—in fact this marvellous economy of words is beyond compare

and adds greatly to the forcefulness of the thought. The famous

artist and author Ruskin well says,—"It is not always easy in

painting or in literature to determine where the influence of

language stops and where thought begins. The higher thoughts are

those which are least dependent on language. No weight, nor mass,

nor beauty of execution can outweigh one grain or fragment of

thought."

Now Jack and Jill are

wrought into a thing of beauty and power with the least possible

expenditure of effort and external show. The author knew what to

say, and he stopped when he was done. And so, whether one regards

the mechanical structure of the poem, the beauty of its style, its

easy flow as it glides smoothly along its limpid path, its rhythm,

pathos and tenderness, it simply challenges all competition.

Throughout, the poem is good Anglo Saxon, and with only three

exceptions every word is a monosyllable.

You will observe that

this poem divides itself into two distinct parts. The first part,

consisting of two lines, describes the ascent or going up of the

heroes, with the purpose of the action. This I shall designate The

Anabasis. The remaining two lines tell the story of the descent or

the Katabasis, I shall call it, that is the going down, with the

tragic ending.

The Anabasis

THE word Jack is

evidently derived from the Hebrew word Jacob rather than the Greek

Johannes, from which the English John is derived. The name was

probably a surname added to the original name of the hero to express

some incident or characteristic of his life history.

You will remember

that the Hebrew-Jacob means supplanter, and that it was given to the

patriarch because of the fraud he practised on his brother Esau.

This gives a certain tenability to the idea that the name was given

to our hero on account of some strategy by which he had got the

better of a rival in winning the affections of the fair one with

whom he is here associated. To my mind the more probable idea is

that the name was given to him on account of his resemblance to the

Hebrew patriarch in another prominent feature of character. It is to

be noted that Jacob of Scripture record was a man of affairs,

eminent as a doer of things. This gives to the name a fine fitness

for the man of exploits described in the poem, and it also

harmonizes with the application of the name Jack to so many

appliances or instruments in economic service spoken of on a

preceding page.

The name Jill, as was

befitting, is of very different type. Mark the softness and delicacy

of its note—the limpid smoothness with which it flows from the lips.

Well matched pair were these, "He for manly vigor formed; for

softness she, and, sweet attractive grace."

And now you will

please note that this was no play day or occasion for vain show, but

rather for arduous and persevering toil. Many there are who make

progress when wind and tide are in their favor, but, when hardship

and hazard assail them they turn back in helpless despondency,–nor

have they, in the vicissitudes of life's journey, reserve force or

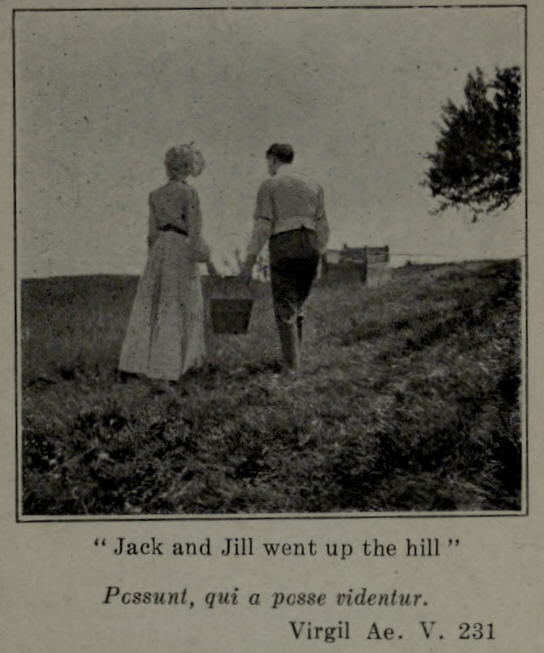

ambition to help themselves. "Jack and Jill went up the hill." Nor

was it an aimless going that is here pictured. No, indeed; they went

"to draw a pail of water." Note the implication in this little word

draw. It was not to turn a tap or handle a pump. The old time

well-sweep with its crotch and pole rises in our mental

vision,;—more probably, indeed the hand pole with hook on the end—undesigned

but unmistakable evidence of the early origin of the poem.

The Katabasis

ALLOW me now to

hasten forward to the second part of our story—the Katabasis. Here

the author wastes no words i n the way of preparation for the

momentous scene he is about to introduce. There are no rhetorical

flourishes, such as—"If you have tears, prepare to shed them now."

The story moves on quietly and calmly without the least

foreshadowing of catastrophe. We are left to fill in for ourselves

the fact that the happy pair have gone on to the well, have filled

the pail with water, and are now returning, tripping down the

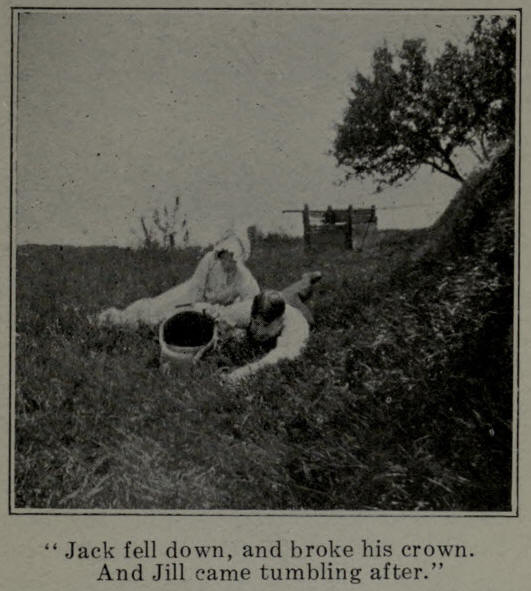

hillside on the homeward way. Suddenly the denouement! The great sad

event breaks in upon us like a peal of thunder from a clear sky.

With all the emphasis of explosion it comes. Nor does the writer use

effort to enforce the impression by comparison or figure of speech,

as you may often find even in Homer, the prince of poets, though he

was. To the intelligent reader there cannot fail to come suggestions

of resemblance and contrast. Especially there occurs the picture of

that other fall when "You and I and all of us fell down." But at the

moment what a medley of ideas present themselves to the mental

vision,—the humorous and the grave come up in quick succession. The

ludicrous holds sway for the moment as we see Jack plunging forward,

dragging after him Jill, his better half, who, holding on to the

pail, comes tumbling headlong over him, and the pair of them,

drenched with water, lying a shapeless heap along the hillside. But,

as one takes in the whole situation mirthfulness is soon checked

giving place to sadness and sympathy.

Just another thought

and I am done. In that other fall that I have referred to, it was

the weaker one who made the first misstep, and Adam, the strong man,

who came tumbling after. Indeed, does it not often occur when one is

on the very verge of success, some mishap or carelessness results in

failure? The wise may not glory in his wisdom nor the strong in his

strength. In the experience of life it is often the unexpected thing

that happens. |