|

TEN miles west from

Davidson College, and two east from the Catawba River, in Mecklenburg

county, stands Hopewell church-Entering near the northwest corner, on

the north side of the burying ground which lies a little south of the

church, and going diagonally to the middle of the yard, you will find a

low gravestone, on the top of which are sculptured two drawn swords, and

beneath them the motto, Arma Libertatis. The inscription is

In

Memory

of

FRANCIS BRADLEY,

A friend of his country,

and privately slain

by the enemies of his

country, Nov. 14th,

1780, aged 37 years.

Tradition says that this

man was the largest and stoutest man in the country—hated by the few

tories—and much desired as a prisoner by the British officers, for the

activity and energy with which he harassed their scouts and foraging

parties, and the fatal aim of his gun in taking off their sentries,

particularly while the army lay at Charlotte.

On the day of his death,

seeing four tories Iurking near his house, he took his gun and went to

capture them, or drive them from his neighborhood. A scuffle ensued, in

which one of the tories succeeded in wresting his gun from his hand, and

with it gave him a fatal wound.

Near by this stone you

may observe a brick wall about six feet long, and two feet high, without

any inscription: that is upon the grave of GENERAL DAVIDSON, who fell by

the rifle-shot of a tory, at Cowan's Ferry, a few miles distant from

this place, as he was resisting the crossing of the British army, in

1781, when Morgan and Green were conveying the prisoners, taken at the

Cowpens, to Virginia, for safe keeping. After the army of the enemy had

passed on, his friend Captain Wilson, whose grave is near by, found him

plundered and stripped of every garment; laying him across his horse, he

brought him hastily by night to this place of sepulture.

Congress voted a monument

to this man—most beloved in his county—a sacrifice to the public

welfare. But the resolution has slept on the records of the

Congress,—and the grave of the general is without an inscription.

The college, patronized

by his children and friends, bears his name, and is rising in usefulness

and reputation.

By the east wail is a row

of marble slabs, all bearing the name of Alexander. On one is this short

inscription :—

John McKnitt Alexander,

who departed this life July 10th, 1817.

Aged 84.

This is -upon the grave

of the Secretary of the Convention in Charlotte, in 1775. By his side

rests his Wife, JANE BANE.

At a little distance

southwardly is the grave of the late pastor of this congregation, JOHN

WILLIAMSON.

Ephraim Brevard, the

penman of the Declaration, and Hezekiah Alexander, the clearest-headed

magistrate of the county, sleep in this yard in unknown graves.

Hopewell and Sugar Creek

are cotemporaries in point of settlement, though, in church

organization, Sugar Creek has the preeminence. The families were from

the same original stock in the North of Ireland; some were born in

Pennsylvania, and some only sojourned there for a time; they were

connected by affinity and consanguinity; and more closely united by

mutual exposures in the wilderness, and the ordinances of the gospel,

which were highly prized.

Scattered settlements

were made along the Catawba, from Beattie's to Mason's Ford, some time

before the country became the object of emigration to any considerable

extent, probably about the year 1740. As the extent and fertility of the

beautiful prairies became known, the Scotch-Irish, seeking for

settlements, began to follow the traders' path, and join the adventurers

in this southern and western frontier. By 1745, the settlements, in what

is now Mecklenburg and Cabarrus counties, were numerous; and about 1750,

and onward for a few years, the settlements grew dense for a frontier,

and were uniting themselves into congregations, for the purpose of

enjoying the ministrations of the gospel in the Presbyterial form. The

foundations for Sugar Creek, Hopewell, Steel Creek, New Providence,

Poplar Tent, Rocky River Centre, and Thyatira, were laid almost

simultaneously: Rocky River was most successful in obtaining a settled

pastor. The others received the church organization and bounds during

the visit of Rev. Messrs. McWhorter and Spencer, sent by the Synod of

Philadelphia for that purpose, in the year 1764. Missionaries bean to

traverse the country very early, sent out by the Synod of Philadelphia,

and the different Presbyteries of New Brunswick, New Castle, and

Donegal.

The enterprising

settlers, inured to toil, were hardy and long lived. The constitutions

that grew up in Ireland and Pennsylvania seemed to gather strength and

suppleness from the warm climate and fertile soil of their new abodes.

Most of the settlers lived long enough to witness the dawning of that

prosperity that awaited their children. They sought the union of

liberty, and property, and religious privilege for their posterity. Year

after year were "supplications" sent to Pennsylvania and Jersey for

ministers, or missionaries, and effort after effort was made to retain

these visitors as settled pastors, but all in vain, previously to 1736;

when the troubles from the Indian war, called Braddock's war, united

with the wishes of the people, and three Presbyterian ministers were

settled in Carolina in that year, or preparations were made for their

settlement—Craighead, and M'Aden, and Campbell. Those were days of log

cabins and plain fare, when carriages were unknown, and the sight of

wheels was an era in the settlements. "'That man was the first that

crossed the Yadkin with wheels," designated the man in whose house the

first court in Mecklenburg was held.

"Times are greatly

altered," said old Mr. Alexander some thirty years ago, on a summer

evening, to the Rev. Alexander Flinn, D.D., of Charleston, South

Carolina, who came to visit his venerated benefactor, in his carriage,

with his wife and servants, "times are greatly altered, Andy, since you

went to college in your tow cloth pantaloons," said the old man, with a

welcome of gladness mingled with fear, lest the simplicity of his youth

had been perverted in that flourishing city.

And times were greatly

altered with both, since their youth, when the one came to Mecklenburg

just "out of his time," and the other left his widowed mother under the

patronage of his friend, to enter upon a college life. Both commenced

life in honorable poverty,—both were enterprising in a young

country,—and both were eminently successful in that course of life in

which choice, and providential circumstances, had led them to put forth

their strength.

John McKnitt Alexander,

descended from Scotch-Irish ancestors, was born in Pennsylvania, near

the Maryland line, in 1733. Having served his apprenticeship to the

tailor's trade, he followed the tide of his kinsmen and countrymen, who

were then seeking an abode beyond the Yadkin, in the pastures of the

deer and buffalo. The emigrants, a church-going and church-loving people

in the "green isle," carried to their new home all the habits and

manners of their mother, the wild and strange residence in Carolina

permitted. A church-going people are a dress-loving people. The sanctity

and decorum of the house of God are inseparably associated with a decent

exterior; and the spiritual, heavenly exercises of the inner mail are

incompatible with a defiled and tattered, or slovenly mein. All regular

Christian assemblies cultivate a taste for dress, and none more so than

the hardy pioneer settlers of Upper Carolina, and the valley and

mountains of Virginia. In their approach to the King of Kings, in

company with their neighbors, the men, resting from their labors, washed

their hands and shaved their faces, and put on their best and carefully

preserved dress. Their wives and daughters, attired in their best, as

they assembled at the place of worship, were the more lovely in the

sight of their friends. The privations of the new settlement were for a

time forgotten; and the greetings at the place of assemblage, from

Sabbath to Sabbath, or whenever they could assemble to hear the gospel,

spoke the commingled feelings of friendship and religion.

The young tailor knew the

spirit of his countrymen, and came to seek his fortune with the poor,

but spirited and enterprising people. Few of them had much money, and

many of them had none. In paying for their lands, the skins of the deer

and buffalo that had fed them, were taken on pack-horses to Charleston

and Philadelphia, as the most ready means of obtaining the necessary

funds. Years necessarily passed before the cattle and horses they took

with them to the wild pastures were multiplied sufficiently for home

consumption or for traffic; about the time of the Revolutionary war,

they constituted the available means, the wealth of the country, as

cotton has been in years past.

The young man brought his

ready made clothes, and cloths to be made to order, and trafficked with

his countrymen, transporting his peltry on horseback to the city, and

returning with a fresh supply of goods, till the droves of cattle and

horses taken to the markets, supplied the inhabitants with silver and

gold for their necessary uses. In about five years, in the year 1759, he

married JANE BANE, from Pennsylvania, of the same race with himself, and

settled in Hopewell congregation. His permanent abode has been known by

the name of Alexandriana. Prospered in his business, he soon became

wealthy, and an extensive landholder, and rising in the estimation of

his fellow citizens, was promoted to the magistracy, and the eldership

of the Presbyterian church, the only church between the two rivers.

Shrewd, enterprising, and successful, a roan of principle and inspiring

respect,—in less than twenty years from his first crossing the Yadkin,

he was agitating with his fellow citizens of Mecklenburg, the rights of

persons, of property, and conscience,—and resisting the encroachments of

the king, through his unprincipled and tyrannical officers, that

oppressed, without fear and without restraint, the inhabitants of Upper

North Carolina.

In less than one quarter

of a century after the first permanent settlement was formed in

Mecklenburg, men tallied of defending their rights, not against the

Indians, but the officers of the crown and took those measures that

eventuated in the CONVENTION of May 20th, 1775, to deliberate on the

crisis of their affairs. Of the persons chosen to meet in that assembly,

one was a Presbyterian minister, Hezekiah James Balch, of Poplar Tent;

seven were known to be Elders of the Church—Abraham Alexander, of Sugar

Creek, John Mcknitt Alexander and Hezekiah Alexander, of Hopewell, David

Reese, of Poplar Tent, Adam Alexander and Robert Queary, of Rocky River

(now in the bounds of Philadelphia), and Robert Irwin, of Steel Creek;

two others were elders, but in the deficiency of church records, their

names not known with certainty, but the report of tradition is, without

aviation, that nine of the members were elders, and the other two are

supposed to have been Ephraim Brevard and John Pfifer. Thus ten out of

the twenty-seven were office-bearers in the church; and all were

connected with the congregations of the Presbyteries in Mecklenburg.

The Declaration issued by

this Contention is the admiration of the present generation, and will be

of generations to the end of tire,—THE FIRST DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

IN NORTH AMERICA. At a hasty view, this declaration made by a colony on

the western frontier of an American province, may seem rash and

unreasonable; but when the race and the creed of the people, and their

habits, are taken into consideration, we wonder at their forbearance;

this classic declaration expressed a deep settled purpose, which the

ravages of the British army, in succeeding years, could not shake.

Neither the Congress of

the United Provinces, then in session, nor the Congress of the Province

of North Carolina, which assembled in August of the same year, were

prepared to second the declaration of ,Mecklenburg; though the latter

appointed committees of safety in all the counties, similar to the

committee in Mecklenburg. The papers of the Convention were preserved by

the secretary, John McKnitt Alexander, till the year 1800, when they

were destroyed, with his dwelling, by fire. But the Rev. Humphrey Hunter

and General Graham, who both had heard the Declaration read on the 20th

of May, 1775, had obtained copies, which have been preserved, and Mr.

Alexander gave one himself to General Davie some time previously to the

fire.

Judge Cameron, of

Raleigh, President of the State Bank, who was for many years a

practising lawyer in the Salisbury District, and afterwards a judge,

says that he was well acquainted with Mr. Alexander, who was frequently

brought to court as a witness in land cases, having been for many years

a crown surveyor in Mecklenburg. There was little regularity in taking

up lands; and claims were found to clash, and frequent lawsuits were the

consequence, and Mr. Alexander was appealed to for bounds and lines.

Being a sensible and social, dignified man, an acquaintance commenced

which was ended only by the death of Mr. Alexander. The Judge says that

the matters of a revolutionary nature were frequently the subject of

conversation; and among others, the circumstances of the Declaration.

Some time after the fire that consumed Mr. Alexander's dwelling and many

of his valuable papers, he met the old man in Salisbury. Referring to

the fire, Mr. Alexaiidcr lamented the loss of the original copy of that

document, but consoled himself by saying, that he had himself given a

copy to General Davie some time before, which he knew to be correct so,

says he, "The document is safe." That copy is in the hands of the

present governor of North Carolina; and is in part the authority for the

copy given in the first chapter of this work. The copies of Hunter and

Graham rest upon the honor of those two unimpeachable men. Happily, they

entirely agree with the copy given to General Davit, as far as that has

been preserved.

The last interview the

Judge had with Mr. Alexander was in Salisbury. Nearly blind with age and

infirm, he was brought down to the court as an evidence in a land case.

The venerable old man sat in the bar-room, listening to the voices of

the company, as they came in. "is that you, Cameron?" said he, as the

sound of his voice fell upon his ear, "I know that voice, though I

cannot well see the man." Infirm, he was dignified: with white hair and

almost sightless eyes, his mental powers remained. The past and the

future were to him more than the present; in the one he had acted his

part well, in the other he had hope; but the present had lost its

beauty. He recounted, in the course of the interviews he had with the

Judge, during the intervals of court, the events of the Revolution,

particularly those in which Mecklenburg took the lead, and referred to

the copy of the Declaration he had given to Davie as being certainly

correct.

Mr. Alexander, as an

elder in the Presbyterian church, was frequently appointed by the Synod

of the Carolinas, during the twenty-four years the two States were

associated ecclesiastically, on important business for the Synod, and

for a number of years was its treasurer. Of undoubted honesty, and

unquestioned religion, he finished his earthly existence at the advanced

age of fourscore and one years.

The reason for the

obscurity in which the proceedings of the Convention in Charlotte were

for a time buried may be found in the facts,—first, the county in which

they took place was far removed from any large seaport, or trading city;

was a frontier, rich in soil, and productions, and men, but poor in

money,—with no person that had attracted public notice, like the Lees

and Henry, of Virginia, for eloquence,—or like Ashe, of their own

distant seaboard, for bravery,—or like Hancock, of Massachusetts, for

dignity in a public assembly,—or Jefferson, for political acumen: and,

second, the National Declaration in 1776, with the war that followed, so

completely absorbed the minds of the whole nation, that efforts of the

few, however patriotic, were cast into the shade. in the joy of National

Independence, the particular part any man, or body of men, may have

acted, was overlooked; and in the bright scenes spread out before a

young Republic, the Colonial politics shared the fate of the soldiers

and officers that bore the fatigues and endured the miseries of the

seven years' wear. Men were too eager to enjoy Liberty, and push their

speculations to become rich, to estimate the worth of those patriots,

whose history will be better known by the next generation, and whose

honors will be duly appreciated.

Some publications were

made on this subject in the Raleigh Register in 1819, and for a time

public attention was drawn to the subject in different parts of the

country. About the year 1830, some publications were made, calling in

question the authenticity of the document, as being neither a true

paper, nor a paper of a true convention. Dr. Joseph McKnitt Alexander,

inheriting the residence, and much of the spirit of his father, the

secretary, felt himself moved to defend the honor of his parent, and the

noble men that were associated in the county of Mecklenburg. Letters

were addressed to different individuals who either had taken a part in

the spirited transactions of 1775, or had been spectators of those

scenes that far outstripped in patriotic daring the State at large, or

even the Congress assembled. in Philadelphia. the attention of all the

survivors of Revolutionary times was awaked; their feelings were

aroused; and they came on all sides to the rescue of those men who had

pledged "their lives, their fortunes, and their most sacred honor."

The Rev. Humphrey Hunter,

who had preached in Steel Creek many years, within a few miles of

Charlotte, and for a number of years in Unity and Goshen, in Lincoln, a

short distance from the residence of Mr. Alexander, sent to the son a

copy of the Declaration, together with a History of the Convention, of

which he was an eye-witness. General Graham, who had grown up near

Charlotte, had been high-sheriff of the county, and was an actor in the

Revolution, and an eye-witness of the Convention, did the same. From

their accounts, the historical relation in the first chapter of this

volume was taken. Captain Jack, who carried the declaration to

Philadelphia, gave his solemn asservation of the facts, as an

eye-witness of the Convention, and as its messenger to Congress. John

Davidson, a member of the Convention, gave his solemn testimony, writing

from memory, and not presenting any copy of the doings, but asserting

the facts and general principles of the Convention. The Rev. Dr.

Cummins, who had been educated at Queen's Museum, in Charlotte, and was

a student at the time of the Convention, affirmed, that repeated

meetings were held in the hall of Queen's Museum, by the leading men in

Mecklenburg, discussing the business to be brought before the convention

when assembled. Colonel Polk, of Raleigh, who was a youth at the time,

and who repeatedly read over the paper to different circles on that

interesting occasion, affirmed and defended the doings of his father, at

whose call, by unanimous consent, the delegates assembled. Many, less

known to the public, sent their recollections of the events of 19th and

20th of May. A file of New York papers, published during the Revolution,

gives the declaration and doings of May 30th, in which independence is

asserted in language as strong as in the paper of the 20th, and the

civil government of Mecklenburg was arraigned, a government that was

paramount till after the meeting of the first North Carolina Provincial

Congress. A file of Massachusetts papers, printed at the same time,

gives the same documents. Relying on these affirmations and documents,

the son rested securely for his father's honor, and the honest fame of

his compeers. By the order of the legislature of North Carolina, these

facts and assertions were made a public document. There remains not a

man at this day, who saw the assembly of delegates in Mecklenburg.

Happily, the son collected the evidences of his father's political honor,

before the witnesses had all passed to the land where the truth needs no

such evidence, and had joined the band of inunortal patriots.

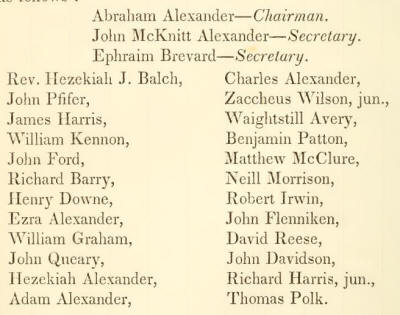

The names of the persons

composing the convention, as given in the State documents collected by

Dr. J. McIinitt Alexander, are as follows

In searching his father's

papers that escaped the fire, he came across another document of

exceeding value, in the handwriting of Ephraim Brevard, the draughtsman

of the Declaration, giving, under the name of Instructions to the

Members of the Provincial Congress in 1773, the ideas of civil and

religious liberty held by these patriotic men. This paper is given in

full in the third chapter, and gives an opportunity of judging whether

the views of liberty held by these have or have not had the sanction of

the people of the United States.

A friend that knew the

son, gives the following obituary notice Died, on the 17th ultimo (Nov.,

1841), at Alexandria, the time-honored seat of his ancestors, in

Mecklenburg county, N. C., Dr. J. MCKNITT ALEXANDER, in the 67th year of

his age.

"Dr. Alexander was an

alumnus of Princeton College in its palmiest days. He had early

developed indications of not only genius and talents, but the highest

attributes of intellect, sound judgment and profound thinking. One of

the usages of the enlightened, estimable, and Christian community in

which he was reared, was, that each family should educate one son and

devote him to the service of the Church. In accordance with this

excellent usage, it was determined by his parents that the natural

endowments of Joseph should receive the culture and finish of a thorough

collegiate education, and the school at Princeton was selected for the

purpose. Here erudition and science matured the germs of usefulness and

distinction, which had in his boyhood given such high promise of a

fruitful harvest. IIe graduated with eclat, and returned to his native

home—riot, as had been fondly hoped by his pious parents, to engage in

the study of divinity, and to consecrate himself to the holy ministry.

This, their cherished expectation, to their bitter disappointment, was

never realized. He studied medicine under a distinguished preceptor, and

after becoming thoroughly indoctrinated in the "Æsculappian mysteries,"

engaged in the practice of physic, from which he acquired not only

professional reputation but wealth and even affluence. The pure duties

of humanity imposed upon him by his profession, were ever performed with

punctuality and cheerfulness, and throughout his long life, no citizen

had a more enviable character for integrity, public spirit, and private

virtue. He was distinguished for his practical judgment and plain common

sense—a trait the more remarkable as it was accompanied in him with the

scintillations of genius and the sprightliness of a vigorous

imagination. fie thought quick, yet deep and accurately. What others

found by pains-taking, search and tedious investigation, he obtained

intuitively. To look at a subject at all, was to penetrate it with an

eagle's glance, to touch was to dissect, to handle was to unravel. He

wrote well, yet his productions possessed few of the embellishments of

art and none of the ornaments of style, though l always enlivened and

brilliant from the flashes of a true and inflate eloquence."

"Doctor Alexander, though

a child of the church, and the son of the most exemplary and pious

parents, had passed the meridian of life before he became a professor of

religion. Does the pride of intellect or the glitter of human learning

lead us to doubt the truth of divine revelation? The avalanche of

infidelity, put in motion about the period of the Doctor's maturity by

Montesquieu, Voltaire, Diderot, D'Alemhert, Buffon, and Rousseau,

threatened to extinguish the best hopes of man, and deluge our sin

ruined world with a cold and cheerless scepticism. The infection of this

poison may have temporarily obliterated the lessons of his youth, or

weakened their influence upon his principles; it was never able,

however, to seduce him from the paths of virtue. His purity, his

probity, his honor remained unscathed by the lightning of the French

philosophy. It may for a time have diverted his attention from spiritual

things, but when ambition became chastened by age, in the maturity of

his intellect, and at a period of life most favorable for a calm and

deliberate examination of the. great truths of the Christian's Bible,

and the Christian's faith, and the Christian's hope, he believed that

Bible, he exercised that faith, he was animated by that hope. He became

a worshipper of the God of his fathers, connected himself with the

Presbyterian church, and continued through life, until the infirmities

of old age prevented, to be active in the promotion of its interests, in

alleviating and ameliorating the condition of men."

Beyond the flight of time,

Beyond the vale of death,

There surely is some blessed clime

Where life is not a breath."

After its organization,

in 1765, Hopewell was for a time associated with Centre in maintaining

the ordinances of the gospel. But at the time that Rev. S. C. Caldwell

was called to the church and congregation of Sugar Creek, this church

united in the call, and afterwards engaged the pastoral services of that

faithful man, till 1805, when he removed from their bounds, and gave up

the care of the church.

During the time of Mr.

Caldwell's ministry, the two sessions of the churches under his care,

feeling the pressure that was upon them, formed a union for mutual help.

The following paper reveals the spirit.

"May 13th, 1793. The

Sessions of Sugar Creek and Hopewell had a fall meeting on the central

ground, at Mr. Mons. Robinson's, and entered into a number of

resolutions, as laws for the government of both churches."

"NORTH CAROLINA,

MECKLENBERG COUNTY,

May 5th, 1793.

"We, the Sessions of

Sugar Creek and Hopewell congregations, having two separate and distinct

churches, sessions and other officers for the peace, convenience, and

well-ordering of each society, and all happily united under their

present pastor, Samuel C. Caldwell, yet need much mutual help from each

other in regard of our own weakness and mutual dependence, and also in

regard to our enemies from without. Therefore, in order to make our

union the more permanent, and to strengthen each other's hands in the

bonds of unity and Christian friendship, have, this 13th day of May,

1793, met in a social manner, at the house of Mons. Robinson. Present,

Robert Robinson, Sen., Hezekiah Alexander, Wm. Alexander, James

Robinson, Isaac Alexander, Thomas Alexander, and Elijah Alexander,

elders in Sugar Creek. John M'Knitt Alexander, Robert Crocket, James

Meek, James Henry, Wm. Henderson, and Ezekiel Alexander, elders in

Ilopewell, who, after discussing generally several topics, proceeded to

choose Hezekiah Alexander chairman, and J. M'Knitt Alexander, clerk, and

do agree to the following resolves and rules, which we, each for

himself, promise to observe." (Then follow five resolutions respecting

the management of the congregations, as it regards the support of their

ministers, inculcating punctuality and precision; and also respecting a

division of the Presbytery of Orange into two Presbyteries.)

Then follow eight

permanent laws and general rules for each Session. Tile 1st concerns the

manner of bringing charges against a member of the church, that it

"shall be written and signed by the complainant," and that previous to

trial, all mild means shall be used to settle the matter.

"2d. As a church

judicature we will not intermeddlc with what belongs to the civil

magistrate, either as an officer of State, or a minister of justice

among the citizens. The line between the church and state being so fine,

we know not how to draw it, therefore we leave it to Christian prudence

and longer experience to determine."

The other resolutions are

all found in the Confession of Faith, in their spirit, in the rules

given for the management of a single session, With this exception, that

it was determined that iii this joint session, "A quorum to do business

shall not be less than a Moderator and three Elders;" and that in

matters of discipline there shall be "no non liquet votes permitted."

This union of the

sessions was productive of most happy consequences to the two

congregations, particularly during the struggle With French infidelity,

and had the effect to preserve the spirit of Presbyterianism, and of

sound principles, and free religion.

The elders were jealous

of any intermingling of Church and State, even in the proceedings of

sessions, and endeavored to keep both civil and religious freedom,

entirely separating political and ecclesiastical proceedings as

completely as possible. All the difficulty probably arose from the fact

that some of the elders were magistrates, and they feared lest, in the

public estimation, or their own actions, the two offices might be

blended in their exercise. |