|

THE PARKS AND BOUVELARDS OF CHICAGO-THEIR BEAUT'Y AND GREAT EXTENT-THE

UNION STOCK-YARDS-THE BARTHOLOMEW OF PIGS-A FOURTEEN MILES LONG

STREET-WATER WORKS ON A GIGANTIC SCALE-A BIG THING IN SAFES.

On the following day our friend had arranged to drive us to the

stock-yards, and to visit several of the public parks by the way. Besides

the parks within the city boundary, there are seven on the outskirts,

ranging in extent from two to five hundred acres each, and situated from

two to four miles distant from each other, all being connected by

well-kept boulevards, extending from the one park to the other, and

forming over thirty miles of a continuous carriage drive, exclusive of

what is within the parks. We were informed that it was in 1869 that the

State authorised the formation of this chain of parks, the ground previous

to that time being a barren prairie. That such a transformation could be

accomplished in so short a space of time is almost incredible. The work is

more like the growth of a century. The boulevards, varying from two to

three hundred feet in breadth, are beautifully laid out on each side of

the

carriage drive, with an endless variety of design in flower plots

and shrub beds. In the parks there is an enormous extent of well-dressed

lawn, very artistically laid out with carriage drives, serpentine walks,

and artificial lakes connected by little streamlets, crossed here and

there by rustic bridges. We observed in passing a corner of one of the

lakes, under the shelter of a plantation, a wharf and a fleet of boats,

with an attendant, kept there for the use of the visitors. There are also

conservatories, zoological gardens, restaurants, hotels, and stabling. In

short, there is no expense spared to make the boulevards and parks of

Chicago a resort where the citizens can enjoy themselves to their hearts'

desire.

Paris, with its boulevards, and Versailles, with its artificial lakes, are

far behind Chicago. However, there is one advantage that Paris

possesses—it is placed, as it were, in a large natural basin, and there

are many points where you can get into a position on the elevated rim of

that basin, and take in the whole extent of the city at a glance; whereas,

Chicago being situated on an extensive prairie, cannot be viewed to

advantage except from towers or high buildings within the city.

Leaving the parks, we shape our course for the Union Stock Yards, which

are about seven miles distant from the centre of the city, from which

there is a conveyance every few minutes by either car or rail. The yards

occupy 345 acres of land, all laid out into pens very much in the same

manner that a city is laid out with streets, crossing each other at right

angles. There is accommodation for over J30,000 head of live stock at one

time. Direct communication is had with all parts of the country, eighteen

different railways carrying their cargoes direct into the yards. The

slaughtering and packing-houses are very extensive buildings, several

storeys in height, and placed alongside of the pens, with which they have

a connection by an incline gangway leading from the pens to the top flat

where the killing is done. We visited one of the most extensive (Mr

Armour's work), who has 40 acres of the pens set apart for his own use.

When killing operations are going on, there is a party to keep the incline

gangway always full of hogs, which are driven into a pen in the upper

flat, at the place of execution. This pen holds from ninety to a hundred

hogs, and when closely packed the door is dropped down, and four strong

young men step in amongst them, each seizing one by the hind leg, to which

he fixes a chain, the other end being' attached overhead to a pulley, to

which a man attends and sets it in motion. The hog is suddenly jerked up,

being suspended by one of the hind legs and the head hanging down; the

chain is then transferred to an overhead iron rail or gallows set on an

incline, so that, with a slight push by the hand, it slides forward to the

executioner, who stands with knife in hand on a little platform in the

corner of a long trough, and with a quick motion of the hand he quietly

performs his diabolical work, disposing of five of his victims every

minute until the pen is emptied, when it is again speedily filled, and the

process repeated. He could easily despatch three times the number, could

they only be suspended and forwarded to him. In the intervals, he eyed us

with a smile on his countenance, inviting us to try our hand, but we

gratefully declined the kind offer. It was difficult to make out what was

being said, the noise being such as you might imagine to be in the

neighbourhood of a thousand pairs of bagpipes in full blast!

As the carcases passed from the hands of the executioner, the blood flowed

into the trough under, from which it is drawn off in the fiat beneath. On

reaching the end of the trough, the carcases are dropped into a long

cistern full of boiling water, the width of the cistern being the length

of a hog. At the extreme end there is a curved iron grating, the full

width of the cistern, that is continually dipping down and lifting out the

water, and when a carcase is put in at the one end, the grating lifts one

out at the other and throws it on a table, where it is passed through a

machine which scrapes off the hair. The carcase is again suspended to a

rail by both the hind legs, and is passed on where a number of men are

kept opening and disembowelling, who in turn pass it on to other men, who

divide it in two, when a man seizes each half and carries it to a bench,

where another stands with a heavy cleaver in his hand, and with two

strokes he severs the fore ham and hind ham from the side. Other three men

are kept constantly carrying off, one the fore and another the hind ham,

and the third the side, each to separate sets of men who are kept dressing

their respective parts.

We were then taken to where the sausages were being made, and to the

curing and packing. Considering the nature of the work, it was surprising

to find in all the departments everything so scrupulously clean. This may

be accounted for owing to there being a plentiful supply of hot water for

washing, and steam power keeping fans in motion, sending a current of

fresh air through ice into every part of the works. Our visit was in the

month of July, when least business was being done. The daily killing at

the time of our visit was three thousand hogs and five hundred head of

cattle, employing about thirteen hundred men in the work. In the cool

season, Armour's daily killing averages eleven thousand five hundred hogs

and seven hundred and fifty head of cattle, employing three thousand

workmen in the different operations. Within the stock-yards there is a

large hotel and stabling for several hundreds of horses, as well as a bank

and an office of the Board of Trade.

Throughout the whole work, in every department, the strictest regard is

paid to the division of labour—the extent of the operations rendering such

comparatively easy. In the immediate neighbourhood of the yards there is a

large town inhabited by the employees and their families. Returning to the

city, the most direct course is by Halsted Street, which passes the stock

yards right through the city, and is fourteen miles long in one straight

line. By the way, there was pointed out near the centre of the burned

district the only house that had escaped the great conflagration. Seeing

that it was constructed of wood, we inquired how it had not shared the

fate of the others, and learned that the proprietor, when the fire was

distant, seeing that danger was approaching, set to work and stripped the

inside of the house of carpets, bed-clothes, table-cloths, &c., and spread

them over the outside of the house, and kept them well saturated with

water while the fire was raging in its vicinity.

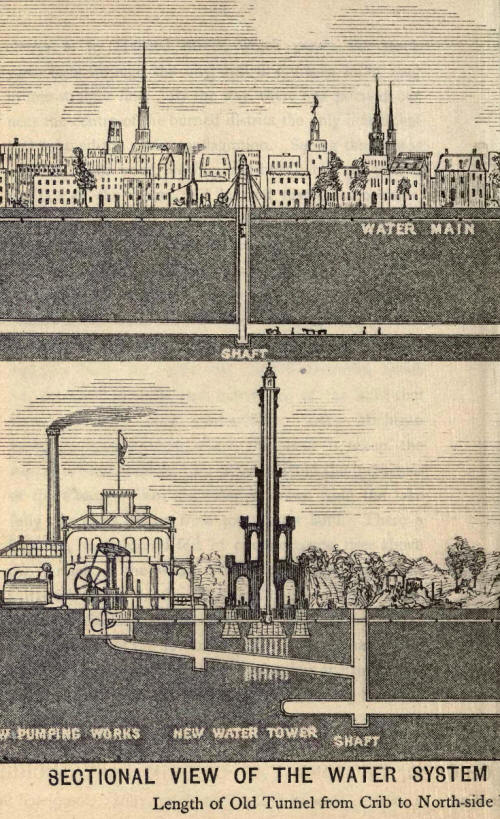

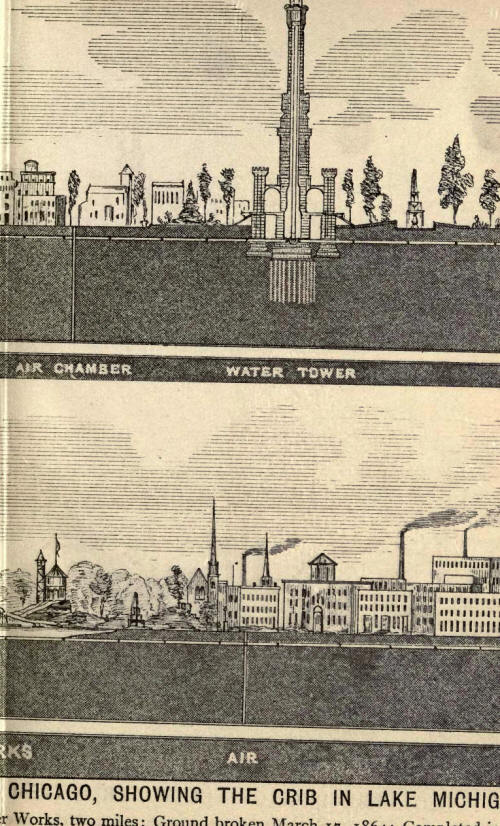

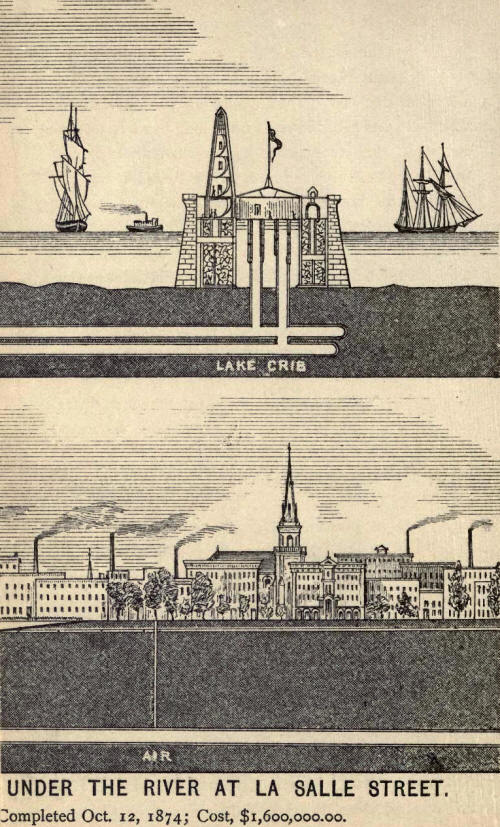

Leaving the straight course, and passing through Lincoln Park, we reach

the City Waterworks, which are the most gigantic and marvellous of the

kind that have ever yet been undertaken. Lake Michigan being the fountain

from which the water is taken, the supply is inexhaustible. In order to

avoid the impurities of the Chicago river, the water is drawn from the

lake fully two miles distant from the nearest land. There a building, one

hundred feet in circumference, rises above the surface of the water, which

at that point is about thirty-five feet in depth. That building is founded

on the bottom of the lake, and is surmounted by a lighthouse and signal

station for the accommodation of vessels navigating the lake. In this

building there are fitted up apartments for the waterman and his family,

the centre being reserved for the shafts that admit the water to supply

the city.

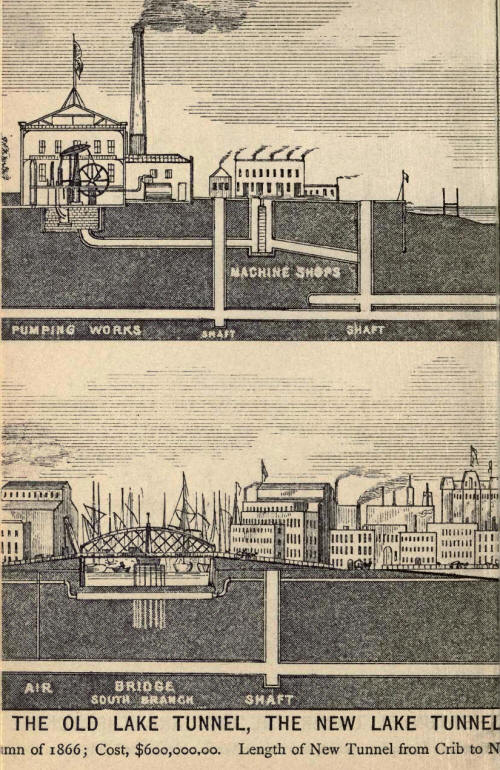

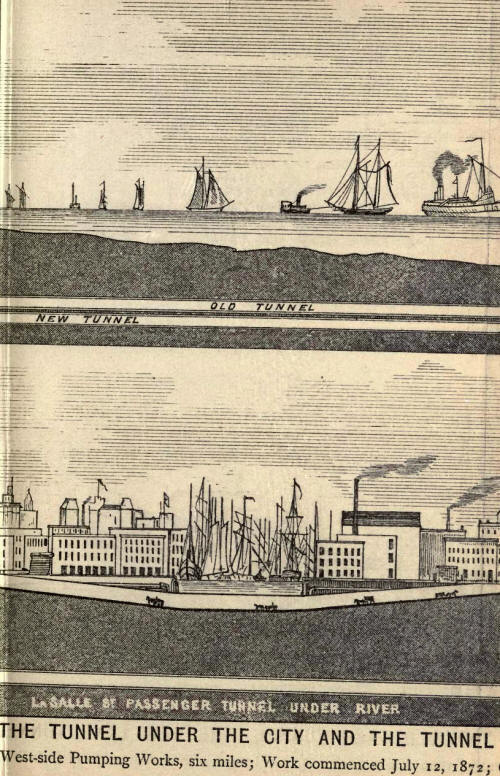

The first tunnel, begun in 1864 and completed in 1867, is about two and

a-quarter miles long, and five feet inside diameter. The second tunnel was

completed about six years ago, and is six miles long by seven feet in

diameter. Both tunnels are water-tight, built of brick, and in each case

fully two miles of the tunnel is carried out under the bottom of the lake

at a depth of seventy feet from the surface of the water.

Each of the tunnels has an upright shaft rising in centre of the building

on the lake, where the inlet of the water to the tunnel is regulated by

the superintendent. The water being admitted there, flows through the

tunnel to the pumping station, where it rises to the level of the surface

of the lake in a large receiver near the pumps. The station we visited is

on the short tunnel, and has four steam engines constantly at work, these

having a combined power of three thousand horses, throwing at each stroke

2750 gallons of water into a large upright iron pipe or tower 175 feet in

height; from this tower the water gets its pressure for distribution over

the city. Round the outside of this iron pipe is built a stone wall with a

space all round, where a spiral stair ascends to the top of the tower

which terminates with a balcony that is free to visitors, and from which

there can be had a very good view of the lake and city.

This is not the only source from which water is got. Many manufactories,

some of the parks, also the stockyards, get their supply from Artesian

Wells. Several years ago a party who had been affected by the oil mania

commenced to bore in the hope of finding oil. Though disappointed in their

expectations, they were rewarded by the discovery that an abundant supply

of water could be obtained at a depth of from seven to nine hundred feet,

and there are now between forty and fifty of these wells throughout the

city, some of them supplying large quantities of water.

We now take the train for Boston, distance about 960 miles, fare £4 and

time 36 hours. Boston bears a great name as a fine city, with many

attractions. However, we were not so favourably impressed with it as with

some of the other cities we had the pleasure of visiting. No doubt it has

attractions in the shape of extensive business premises, fine buildings,

beautiful parks, and within the ast ten years the business part of the

city has had the advantage of the purifying influence of the flames.

Still, the Local Authorities have not availed themselves of that

opportunity of having it re-modelled. Fine buildings have been re-erected

on the old lines. The streets are narrow and very irregular, with a great

many triangular blocks—so much so that it is almost impossible for a

stranger to pilot his way without the assistance of a guide. In the

central part of the city, near to the Post Office, is a large fire-proof

block, known as the Equitable Building, which is deserving of notice on

account of its being used as the vaults and offices of the "Security Safe

Deposit Company," who carry on a business that is scarcely known in this

country, while with the Americans it is almost indispensable on account of

the combustible materials of which the greater number of their buildings

are constructed. This building is thoroughly fire-proof. The roof and

floors are altogether stone, brick, and iron, and the stairs are marble

and iron, there being little or no wood used in the erection. As a

building, it has altogether a very neat, substantial appearance.

Notwithstanding that, the strong iron gratings of the external openings,

embedded in the stone walls, with the heavy iron door and shutters, and

the court-dressed officials that guard the entrance are more sug-

gestive of a prison than of a place of business. On entering, you pass

into a large, handsomely-finished hail, where attendants are in waiting to

receive customers and assist them in getting access to their property, and

to restore it to the safe, when they have their business done. The vaults

containing the safes have all double doors, constructed of iron and

secured with combination locks, which no one man can open. It requires two

men acting together to effect an entrance, and that can be done only

during business hours, which are from 9 A.M. to 4 P.M. These doors have in

addition self-acting time- locks, which fasten on the doors being closed,

and are governed by clock-work, and when closed at 4 P.M. it is impossible

for any one to open them; even those who know the combination of the other

locks cannot effect an entrance before nine o'clock next morning. There is

also direct electric telegraphic communication between these locks and the

nearest police station, so that should there be any tampering with the

locks, the alarm is at once given at the office, and the police are

speedily at the point of attack. These premises are always under the

supervision of armed watchmen, who are constantly traversing round the

vaults. At short intervals, each watchman has to lass over his beat, at

each extreme of which there is a recording electric clock, which

communicates with the manager's residence. Should any of the watchmen

neglect to be at the clock at the right time to record his visit, the

alarm is sounded at the manager's house, and information conveyed to him

on whose beat the neglect has occurred.

The business of this company is to receive for safe keeping, against

either fire or burglars, all kinds of valuable property, such as wills,

title deeds, bills, bonds, money, jewellery, &c. All classes patronise the

company—private individuals, trustees, merchants, corporate bodies, and

bankers—some of whom, we are informed, deposit their money and valuable

documents with the company every evening and remove them back to their

place of business every morning. Adjoining the vaults, there are

comfortable rooms of various sizes, where any person who has documents

deposited can have a room to examine them at his leisure. There are larger

rooms, where trustees or corporate bodies can meet and hold consultations

and examine their documents without the necessity of removing them from

the premises. There is also a spacious reading-room, where the merchant

patrons can consult the daily commercial papers, and also have telegraphic

communication with every important city in the States. Within the walls

there is still a considerable quantity of unappropriated space where safes

can be fitted up when required.

Depositors can be accommodated to the extent of their requirements. The

safes in the vaults being divided into various-sized compartments, the

smallest size being two and a-quarter inches high by four and

three-quarter inches wide by twenty-one inches deep, for which the rent is

£2 per annum; while one at twenty- one inches high by fourteen inches wide

by twenty-one inches deep, is £20 per annum. There are several sizes

between these two. That rent entitles the depositor to the use of a room

and assistance of a servant at any time he requires to examine his

property. At the above rate, a safe nine feet wide by eight feet high,

divided into the smallest size, will yield an annual rent of over £1,100

sterling. Some of the safes are divided into larger compartments, so as to

hold tin cases or trunks, silver-plate, paintings, &c., and when deposited

in such packages are charged one per cent, on the owner's estimate of the

value. If an extra bulk compared to the value, then special rates have to

be arranged for.

|