|

“And it was so-from day to

day

The spirit of the plague went on,

And those at morning blithe and gay,

Were dying at the set of sun.”

J.

G. WHITTIER.

IN the spring of 1881,

Kaumpuri (the plague), - which is terribly dreaded by all, from king to

slave, broke out suddenly in the country. It was probably due to the drought

and consequent. famine of the previous year, when many died, and many more

had to struggle for life by eating roots of plantains and other trees.

Mackay believed that the filthy state of the huts in which the Baganda live

had not a little to do with it. Kaumpuri is also the name of the

lubare, or deity supposed to be the cause of the evil. Several sorcerers

belong to this deity, and are believed to be possessed of the evil spirit,

and of its power to visit any particular house and garden, when the natives

at once flee. On this occasion it broke out in the royal palace among the

king's wives, several of whom died in a few hours. Hence there was a

stampede of the king and chiefs from Rubaga to the hill of Nabulagala. One

sorcerer set to work to check the disease. He made a pipe some five or six

feet long, in which he put some noxious weeds, and walked round the courts

of Rubaga, smoking the formidable charm! Mackay remarks that the treatment

might disinfect the place, or at any rate himself.

Meantime Mackay and Pearson

endured many hardships and privations. For many days at a time they had

nothing but plantains to eat, and to buy these they had parted with all the

clothes they could spare. The following entries in his journal at this time

give a glimpse of the much-talked-of “luxuries of missionaries.”

“March 13th, 188I. -

The hours of daylight are very precious, as we have only one candle left,

and we do not know when we may get more. Fat and butter are not to be had.

Hence every hour of light must be filled up with useful work, for after dark

we must just sit in the dark, as we have had to do for some time, and for

many days at intervals before. I miss a nightlight, especially for reading

or writing a little. I have always grudged the hours of day for these

purposes, but now I must do without the evening hours of reading for

improvement. How I thank my dear father for my well-stored mind, which

enables me to enjoy many an hour’s meditation.”

Then comes a red-letter day,

which missionaries in distant lands can well understand.

“March I4th. - I had

been busy all forenoon translating, and had set to work continuing printing

our first book of texts, etc. I had my composing-stick in hand, and was in

the middle of the line ‘God so loved the world that He gave’ - when I heard

a shout outside. It was our boys welcoming the man whom we had sent to

Usukuma two months ago. On goes my slouch-hat and white canvas coat, and out

I run to hear the news, and open my eyes for letters from home.”

“Question and question tumble

one on the top of the other, with fragments of answers and salaams from this

and that white, black, and yellow friend in the lands south of the Nyanza.

Pearson opens the small bundle which had left the hands of Stokes that

morning on the lake, where he and Rev. Mr. O'Flaherty had arrived the

previous day. God be praised for their preservation from every danger by

land and lake, and for this bundle of letters from England!”

“Pearson is letter ‘sorter.’

‘Mackay, Mackay, Mackay, Pearson, Mackay, Mackay.’ Three of mine to

everyone of his, and I chuckle with glee and think of the contents. My total

is nearly forty letters, and Pearson has fifteen. Not satisfied, but craving

more, I call out, ‘Where are my papers? I know my folks always send me lots

of papers!’ We only hope that the papers will come by Stokes himself, and we

proceed to read what we have. My last from home was dated June 5th, 1880;

now I have a pile running on to September 23rd (six months ago). Other

letters from England and Germany and the interior of Africa fill up the rest

of my budget.”

“The moon is full and the sky

clear and calm, and by this light I continue to read long after the sun is

down. Our remaining candle we light, and read and remark on events till a

late hour.”

“Many good men are dead, but

saddest of all to us is the news that our dear and true friend Rev.

Prebendary Wright is now no more. Salisbury Square seems strange to us

already”

“We have nothing to go upon

here as to when to expect letters. After we get a packet, we expect nothing

for three months, and then we begin to think that before another three

months are over we may hear again. When we send a mail off, we have much

more trouble than merely stamping and posting. First, we have to consider

which of our men we can spare, then some of these are sure to refuse; so we

try others, till we make up a complement of four. Then each has to get

calico in advance, to wear, and calico to buy food with on the way, as also

cowrie shells. Next, each has to get a gun and powder and caps, and

invariably each has some request of his own - petty debts which we must pay

for him, etc. Meantime we have arranged with the leader of some canoes that

mean to start for the embarkation of our men. His demands have to be

satisfied, else the letter-carriers will be refused passage when they reach

the lake. Frequently, after paying for their passage, they have had to

return to us, as they were refused permission to go on board! When their

backs are turned, I am glad, for generally we have been writing till very

late the night before, and in the morning the packet has to be made up and

sealed, and then sewed in strong calico, with a band so as to be slung round

the neck of the carrier. What would we not give for just a good Scotch

herring-boat on this lake! But the time is, I hope, near, when I shall be

able to set about building a steam launch for ourselves.”

A new era dawned on the

Mission on the 18th of March, with the arrival of the Rev. P. O'Flaherty.

Mr. Stokes accompanied him, but started again for the coast on April 1st,

and a few days afterwards Mr. Pearson also left the country. Mr. O'Flaherty

brought with him the three Baganda envoys who had been sent as ambassadors

to Queen Victoria, but it is questionable whether their visit to England in

any way promoted the interests of the Mission, for they all returned to

their old ways and their old superstitions, and one of them (Namkade)

conceived a great dislike to white men, and continued ever after to be an

open enemy to the missionaries. On one occasion he bribed the katikiro with

presents he had received in England, to take back from the missionaries a

piece of ground the king had presented them with.

The king was very fond of

controversy, and greatly enjoyed the discussions at court between Mr.

O'Flaherty and the Mussulmans. Indeed, he frequently, out of a spirit of

pure mischief, asked questions which he very well knew would lead to bitter

feeling and angry words. Each time the Arabs breathed out venom and opposed

Mr. O'Flaherty to the utmost of their power.

Still many pupils - chiefs

and slaves - were allowed to go to the Mission Station, which was the desire

of Mackay's heart, as even although after a few months they might be

suddenly ordered off to some other part of the country, the good news was

disseminated. The Baganda are very eager pupils, and are besides very clever

at learning to read and write. As a rule it only took Mackay a couple of

months to teach the younger lads to read fluently, although they did not

even know the alphabet at the beginning of that time.

Regarding his teaching, he

says: “I feel sure that in this respect alone the Christian influence of the

Mission is very great in the country; it is unquestionably felt, otherwise

there would be less fear at court of our perverting the minds of the youth

of the land.”

The work of God began to take

root again, as it did during the first happy months of Mackay's residence in

the country, and his heart was greatly encouraged, notwithstanding the open

hostility of the Arabs, and the trials caused by the French Romish priests,

who, although on good terms with the Protestant missionaries, never ceased

to play their old game of proselytising.

Secular work also prospered,

and Mackay describes himself humorously as “engineer, builder, printer,

physician, surgeon, and general artificer to Mtesa, Kabaka [The

word kabaka is higher than king, being synonymous with Kaiser]

of Uganda, over-lord of Unyoro, etc.”

By the month of June the

plague greatly increased, and in most cases proved fatal. Many applied to

Mackay for medicine, but the disease being new to him he declined to

prescribe for it. He, however, did his utmost to get the king first to

understand, and then to enforce some sanitary measures, so as to check

and ultimately stamp out the pestilence. The king himself had long been

ailing, and the “Queen Dowager” (of whom Captain Speke says much, in his

“Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile”) came to visit him. She

was one of Suma’s wives, and generally looked upon as Mtesa’s mother; but

his real mother was sold by Suma to an Arab, and by him carried out of the

country - where?

As Uganda has its kabaka or

king, so there must always be a mother to the king, occupying her own

capital, holding her own court, and having her own chiefs, each holding an

office corresponding to Mtesa’s officers of state, e.g. katikiro

(premier), Mkwenda, Sekibobo, etc. The old heathen had been a great

hindrance to the entrance of Christianity into the country. When Mukasa,

the incarnation of the lubare (or the devil), went to court in great state,

at Christmas, 1879 and Mtesa, at Mackay's earnest instigation, refused to

see the national deity, it was old Namasole, the Queen Dowager, and her

court of females, who succeeded in persuading the king to abjure

Christianity. After that, however, she did not interfere with the

missionaries.

She seldom visited the king,

and on this occasion her object was to prescribe for his complicated

maladies - the cure being that he remove from the country all the donkeys!

Now, Mackay had procured a

donkey for Mr. O'Flaherty to ride on to court every day, and had forged a

bit and a pair of stirrups, and manufactured a saddle. The mission station,

at this time, was situated three miles distant from the royal quarters, and

as Mr. O'Flaherty was getting old, he felt the walk there and back too much,

in the great heat. Mtesa at once remembered the mission donkey and objected

to her Majesty’s proposal, but of course he had to yield. Accordingly, some

pages were sent to Mackay to say, that “the king wished the loan of the

donkey for Pere Lourdel, as he was sending the latter to see a distant chief

who was very ill!” Mackay believed the tale and let the ass go. It is

needless to say, it was never again seen. Mr. O'Flaherty, however, was able

to walk to court pretty frequently, and on one of these occasions Mackay

gave him a list of six measures, begging him to submit them to the king’s

consideration, for the relief and suppression of the plague.

“1. All persons attacked to

sponge repeatedly every day all over with tepid or cold water, as they find

most soothing. Also to drink plenty of water, hot preferable to cold.”

“2. Each patient to have a

new, small, airy hut built at once, with a bed off the ground.”

“3. Every house where anyone

has been sick or died of the plague to be burnt to the ground, at once, as

also all their mbugus (bark-cloths), etc.”

“4. Every house in the land,

whether of chief or peasant, to be clean swept out once a week (say on

Friday), and new grass strewed on the floor.” [The custom in this country is

to have old hay rotting on the floor as long as the house lasts,

occasionally sprinkling new grass on the top of the old filthy stuff!]

“5. In poor men’s houses, and

women’s quarters, where goats are generally kept in the house, to sweep

clean out every day. Also nuisance not to be allowed in the houses, as is

universal at night”

“6. All dead persons, from

any cause, poor as well as rich, to be buried and not thrown into the

swamps, as is universally done with all the poor and victims of the

executioner.”

“These suggestions Mr.

O'Flaherty took much pains in explaining in open court, and the king called

the attention of the chiefs most strongly to them. What will be the result

remains to be seen, although if the fellows are alive to their own interests

they will attend to the king’s advice to see these suggestions carried out.

I shall be very glad if they take our advice, and life is thus saved. They

may listen next to our lessons for the cure of the greater plague of sin and

eternal death. The Lord grant it!”

“I have heard that all the

dead are ordered to be buried, instead of being thrown in the swamps. Those

killed by the executioners will, I fear, continue to be chopped in pieces

and thrown into the jungle as formerly. The fact that the potters (who get

their clay in the swamps) have been especial victims of the pestilence,

shows, I think, that the swamps have much to do with fostering the terrible

scourge.”

“One result of Mr.

O'Flaherty's instructions is very manifest. On all the roads bands of women

have been set to work to hoe and scrape and sweep all the highways, burning

much of the rubbish, but of course not all. Certain petty officers were

appointed to see the work carried out, and they have already done

wonderfully well. Their method has been to compel the owner of each garden

to clean the road in front of his fence. All poor slaves passing by are, of

course, forced to lend a hand, whatever they are carrying being detained

until they have done a good piece of work. I was much amused the other

evening at seeing two women hoeing on the road near our place, when there

came past a lad with a stick in his hand and a bunch of plantains on his

head. The women ordered him to, help them to carry off the weeds. He

declined, when suddenly one of them - a strong young woman - rushed at him

to catch him. The fellow ran, and the woman after him. Down tumbled the poor

lad, and the stout woman tumbled over him. She seized his stick, and

guarding the bunch of plantains compelled him to take her hoe and work for

her. So the man had to yield to the Amazon and fall to work, amid the merry

jeers of the females. I complimented her on her feat, and walked away.”

“But the outside of the cup

and platter are easily cleaned, and I have seen no attempt made as yet to

purify the filthy houses. Doubtless the very style of building universally

adopted in Uganda must prove unhealthy, even although the inside were

scrupulously clean - which it never is. The houses have no walls; all is

roof, like a beehive, with the grass coming down to the ground, and

therefore the lower part, being buried to carry off the rain, always

rotting. When I show them how to make bricks they will begin to learn how to

build more healthy houses. Some say that the king has ordered all old huts

to be pulled down. That alone will help to diminish disease.”

The year 1881 was a time of

great rain, forming a striking contrast to the drought of the previous year.

After the mission was reinforced Mackay began to build a house for their

accommodation. He writes: “Rain and thunderstorms very frequent, and are

really terrific at times. Close on the equator and near the lake, we are in

the centre of atmospheric disturbance. The rustle of the wind among the

great green fronds of the plantain trees sounds wild, like a cataract.

Squalls rise at any moment from a dead calm, but they never last long,

although they are violent. The roof of my hut is nearly blown off, and leaks

badly in many places. Under the hut, however, the ground brings forth

abundantly, and one may as easily see the crops growing, as the

Irishman heard his cabbages growing larger. I mean to make the house

fire-proof, as far as the materials will allow, and also sufficiently

comfortable for an Englishman to live in. The plan I have fixed upon is

novel. To use sun-dried brick would arouse suspicion, as the Arabs have told

the king that we build military forts with bricks. I am therefore

erecting a great framed structure of wild palm (which is the only wood proof

against white ants and other insects), and a thatched roof, which, with a

wide verandah all round, will keep off rain from the wattle-and-daub walls.

The house proper will have a flat roof of trees and clay, and between that

and the sloping thatch there will be a large space, which we may use as an

upper storey. “Mtesa was much interested in the progress of the house, and

supplied poles, grass, etc.; he also issued an order for all the workers in

wood and iron in the country to go to Mackay for instruction in handicraft,

the old men sending a lad as an apprentice, and the younger ones working

themselves. As the apprentices lived far away, the missionaries asked the

king for a piece of ground on which they might build temporary huts. He at

once increased the mission land to about twenty acres, part of which

contained many hundreds of plantain trees.

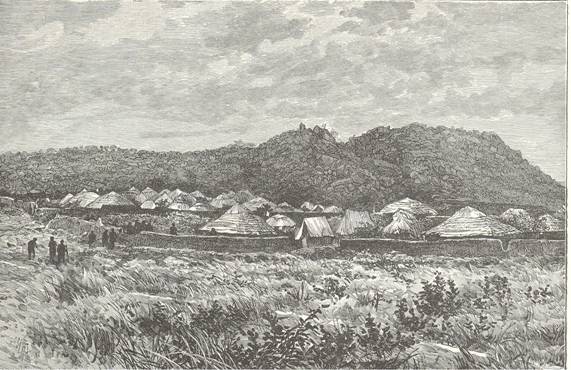

An African Village

Meantime, while Mr.

O'Flaherty represented the cause at court, Mackay was more than occupied in

teaching reading and writing, and other school work, teaching artisan work,

building, designing, planning, providing food for all, and giving medicine

to numerous patients. He says: “I only wish I could spend the whole day

learning and teaching with books ....” Every man should be encouraged to

acquire a thorough knowledge of the language. Others can come and at once

take their place at manual labour, but it must always be the men who have

become most familiar with the language who can teach and preach .... Among

the savages we have got to be savage, or at least semi-savage. Their little

loves and hates we have to take an interest in, perhaps much on the same

principle on which passengers on board ship show great interest in the play

of a porpoise or any other trifle. Still it is necessary that we make

ourselves at home among the people and learn to like them and their

country. Thus alone can we elicit their sympathy, and get them to regard us

as their friends, and thus only too can we become acquainted with the

finesse of their language, so as to be able to express ourselves without

exciting their risible faculties. It is an easy thing for a European to

learn a smattering of these black men’s tongues, just as negroes learn

pigeon-English, but it is a very difficult matter to talk ‘like a nigger,’

and until we can do this we fail in being able to teach them, as we ought,

the knowledge of God and His Redemption.

“The Church of England is not

the best for giving elbow-room to a layman, therefore I am determined, if

God spares me to return home, to go up for ordination by the Church of

England. I am even studying for that at present, my object of course being

to come back to Uganda immediately after taking priest’s orders, for the

mission here is not at an end. I have all along seen that a great and

effectual door is open to our work here, although there are many

adversaries." [Later on, as the work developed,

he gave up all idea of taking orders, believing that it was best in the

interests of the mission that he should continue to be a layman. He found he

had more influence as such. His manual labours brought him into immediate

and constant personal relations with a large number of boys and men, whom he

taught not only to handle tools, but also to read and understand the

Scriptures, and to whom his life was a constant source of instruction. The

unconscious influence of a good man is often more influential than his

verbal teaching, and certainly the living epistle is the most valuable of

all commentaries upon the printed one. ] Some

jottings from his log-book are interesting at this time:-

“Oct. 20th, 1881. -

To-day my pupils finished reading St. Matthew’s Gospel. I think they have

understood it all to a certain extent, and at all events they express their

joy at what they have read, and their belief in the sacred Word. I hope now

to take up the Acts of the Apostles with them, as I have several copies, and

there is great value in bringing before these heathen inquirers the story of

how the heathen world of old first heard the story of salvation.”

“Oct. 23rd. - Soon

after noon we had a very severe thunderstorm. The quantity of hail which

fell was remarkable - great pellets, larger than pigeons’ eggs. For a short

time the ground presented a white appearance, and this under the equator! A

ridge some six inches deep lay along each side of the house, where it fell

from the slope of the roof. Our boys gathered bucketfuls, and I initiated

them into the pleasure of snowballing. Much remained unmelted until the next

day, showing that the temperature of the hail must have been very low. But

what a blasted appearance all the country has assumed since! Every plantain

leaf is turned to shreds, and many trees felled. All the standing crop of

Indian corn terribly damaged. Pumpkins, tobacco, and cassava all leafless,

and the ground strewn with foliage, like autumn in England. The natives

predict much hunger in consequence. Upwards of two inches were shown by the

rain gauge, but the real amount must be much more, for the lumps of hail

rebounded as they fell, like ivory balls.”

“Nov. 6th. - The

country is recovering from the terrible havoc produced by the hail. So

rapidly does vegetation rise, that Stanley described Uganda well, as being

‘a land that knows no Sabbath.’”

“Door and window frames of

smoothly planed hardwood I have been fitting into the new house, to the

great astonishment of all visitors. The walls too we are building up to

plumb and squaring, and soon all posts and wattles will be concealed. This

is the first house of the kind in the land, and people never tire of coming

to see it.”

“Once more Mtesa has been

talking on the subject of marrying the Queen’s daughter! ‘I would put away

all my women,’ said he, ‘and give you a road through the Masai country by

which to bring your ships (!), if only you bring me an English princess.

These Bazungu are strange men; I would give them wives here if they like,

but they have one, only one each in Europe; their heart seems bound up in

that one: I cannot understand it.’”

“Nov. 2Ist. - The

king’s cows are in the habit of wandering about with no herd. They fatten

best in that way. One has been speared by some fellow who wished for a piece

of beef. The cow was afterwards slaughtered for the king’s own use, but over

forty men were arrested and punished severely, while four or five were burnt

alive as a warning to the public!”

“Nov. 23rd. - A young

elephant was captured recently, and of course presented to the king, who

sent it down by a chief to me, saying that he wished to hand it over to my

charge, that I might teach it to obey and carry loads, etc., like Indian

elephants. We were unwilling, however, for such a charge in addition to all

our other work, which is already too much for our time and strength. Neither

could we afford to keep the hungry animal. We therefore sent back word that

if they first built a suitable house to put the elephant in, and supplied

two men to attend it, with food regularly, for the men and elephant,

we should not object to look after the animal. This we knew they would be

slow to do.”

“Dec. 10th. -

Yesterday in court complaints were made that we are building a castle of

stone, and bribing many Baganda, under pretence of teaching reading, to join

us as soldiers to fight in the new fort. ‘They are teaching our children to

rebel,’ said some counsellors; others, ‘They teach evil things;’ others, ‘We

shall arrest all lads who go to the Bazungu to read.’ ‘No,’ said Mtesa;

‘send first some one to spy under pretence of learning to read, and then we

car find out how many go to read and what they are taught.’ A great chief (Kyambalango),

who is an old pupil of mine, ventured to defend us, saying that he ‘had seen

our house, and that it was no fort: that Mtesa had given Mackay, long ago,

permission to build as he liked, - let him therefore go on.’”

Writing home at this time

Mackay says: “Pere Girault has returned from King Roma’s (see p. 159). He

speaks very contemptuously of the place. He did not do so a year ago, when

he went there to establish a station just on hearing that I meant to

reconnoitre there. I look on his troubles there as a judgment from Heaven on

his false dealing with me on the matter last year when we were together. I

cannot but regard the presence of the Romanists in Uganda as a warning to us

to be less lax in our standard for admission into the visible Church than we

might have otherwise been, and at the same time an incitement to us to be

more faithful and more active in the great work of evangelising. If the

Protestants of the world have let three centuries pass before stretching out

their hands to direct the lost negro to the way of salvation, they cannot

expect to begin, at this late date, under the same favourable auspices as

they might have begun upon much earlier. It is also a crying shame to

Christianity that Mohammedans have been here before us. There can be no

possible excuse for our allowing Islam to first degrade all Africa before we

take the first little step to elevate it.”

Mackay toiled in the sweat of

his brow and applied himself to all sorts of manual labour; indeed, there

was nothing he was unwilling to do, so as to remove prejudice, and promote

the spiritual good of the Baganda, and assist the cause of the mission. He

often writes: “Oh that I could win their love, and that they would put away

their childish suspicions and learn that I am their friend!” It was always a

source of regret to him that so much of his time was occupied in building

and other industrial work. He would have liked better to have spent it all

in studying the language, teaching, translating and conversing with the

natives; but his intense earnestness of soul would never alone have

given him the great influence for good which he acquired in the country. His

physical and mental power and his readiness of resource in emergencies (for

which his training as an engineer had peculiarly fitted him), had all to be

brought into play in this pioneer stage of the mission, and attracted around

him vast numbers of Baganda, to “see the wonderful things the white man

did.”

He was always welcomed at the

palace whenever he chose to go. One day he took up a glazier’s diamond with

him, and showed the king how to cut glass. He also produced a yoke, and

showed how oxen are harnessed. Mtesa said: “There must remain nothing more

for white men to know - they know everything!” “We only know yet the

beginning of things. Every year we make advances in knowledge,” Mackay

answered.

“Can Baganda ever become

clever like the Bazungu ?” asked Mtesa.

“Yes, and even more

clever.” The king laughed and said, “he did not believe it.” The chiefs all

laughed too. “Is it not the case,” said Mackay, “that the scholar generally

becomes wiser than his teacher? The skill of the Bazungu to-day is much

greater than their skill a year ago, while to-morrow they will improve on

the wisdom of to-day. The pupil stands on the shoulders of him that taught

him. He sees all that his master sees, and a great deal farther too.”

This they all understood, and

seemed delighted with the idea. The court rose soon after, when Kyambalango

and other chiefs took him by the hand, in the Uganda fashion.

Writing at this time, he

says: “It is very hard to get the natives to do anything. They are willing

enough to stand and see their slaves work, but I insist upon them digging

themselves, along with me, else no food. Of course I shall give a little

calico to steady workers. Here it is where a practical Christianity is so

essential. Any amount of mere preaching would never set these lazy fellows

to work; and if only the slaves work, what better are matters than before? I

have made work so prominent a part of my teaching that I am called

Mzungu-wa Kazi (white man of work). I tell them that God made man with

only one stomach, hut with two hands, implying they should work twice as

much as they eat. But most of them are all stomach and no hands! That I

work with my hands is a great marvel, and should be a salutary lesson.”

Concerning Christmas 188 I he

writes:-

“CHRISTMAS DAY. - All our

Wangwana turned up early, expecting something, as they believed it was a

‘great day’ with us. We gave them four yards of strong calico each, as well

as a hundred cowries per man, to add some luxuries to their beef and

bananas. Having got them all sitting round the room on mats I had spread for

the purpose, I gave them then a lesson on the meaning of the day to the

whole world, and exhorted them earnestly to leave off their life of mere

animalism, and reflect that there is a world beyond this, in which we must

stand before the Great Judge. These men are nominal Mussulmans, but neither

professors nor practisers of the creed, for they know nothing at all of it

save to swear by ‘Allah.’ What would I not give to see some, were it only

one or two of them, coming back again at times to ask something more about

the coming down of God Himself as Man, which I spoke to them of this

morning!”

“Having bought a large

earthenware pot for the occasion, with lots of bananas and native beer, I

got our boys on to cook with all their might. Bundle after bundle of

firewood disappeared in the flames, and ever on I gave out more, while

meanwhile I tried my hand on a semi-dumpling, semi-plum-pudding. We had

asked all our pupils to come, and by midday we had a crowd waiting. All

being ready, we spread mats on the floor, with a spread of

exquisitely green fronds of the banana; then, in came the basketfuls of

mashed mere, and junks of meat. Plenty of salt being our only relish, we

said grace in Luganda, and all fell to with a will.” |