|

ON the death of Dr Steele several changes which had been

contemplated for some time, were carried out in the arrangement of our

agencies in Ngoniland. We were under the necessity of meeting a reduction of

the European staff. From the first we had proceeded upon the plan of making

use of the natives themselves as far as their character and attainments

would allow, and had placed several of the schools in villages around the

chief stations under them. We thus prepared the way for increasing the

responsibilities of such agents. Hitherto they had been under almost daily

supervision of a European, but now we ventured upon placing districts

instead of schools under their charge and withdrawing the Europeans. The

experiment was tried with our best teacher-evangelists, and, as the sequel

will show, was attended with success in all departments of work, while, as

the outcome of it, we were able even to add to the number of our schools.

The Training Institution, under Dr Laws and Mr James

Henderson, was opened to receive pupils in the end of 1895. We at once

selected some from the districts under natives and sent them there for

training, leaving only those who could be satisfactorily attended to by the

native teachers, and who were required in the work of the district. Without

the opening of the Institution it would have been impossible for us to have

carried on our stations without the usual complement of Europeans.

Miss Stewart, who had come out as first female teacher for

the Institution, and had been temporarily located at Ekwendeni for a year,

was at that time withdrawn to the Institution. She successfully

superintended the girls’ schools during her residence. On leaving for her

new work several of the more advanced girls went with her to complete their

training; others who were not chosen to go to the Institution wept bitterly

when Miss Stewart left. The work among the women at Ekwendeni was again left

in my wife’s hands. The requirements of the younger girls were partly met in

the junior and senior schools, and the older women and girls who could not

attend school were taken up by her, as also the school girls for sewing. She

also gave additional instruction to those women who were coming forward as

candidates for baptism. At Hora station similar work was making good

progress under Mrs M°Callum who had large classes composed of women of all

the social grades.

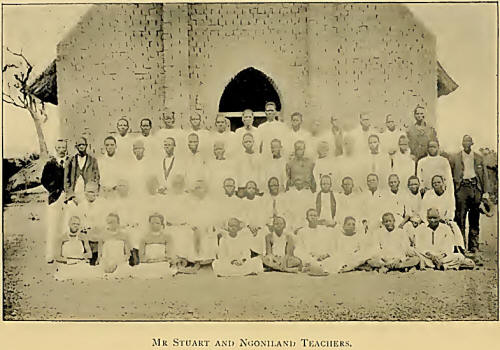

The most important change was made in the staffing of Njuyu

station. It had always been worked by two Europeans, and being the oldest

station, and the arena of all the old battles, the work there was known to

have taken firm root, and was expected to prove a suitable sphere for our

experiment. Mr Stuart, after returning from Scotland, was resident there for

a few months, and when Mr Scott, the teacher at Ekwendeni, left the service

of the Mission to pursue his studies in Scotland, he was withdrawn to

Ekwendeni. Mawalera Tembo was installed at Njuyu to carry on the work of

that district.

Mawalera Tembo has been a faithful worker for many years. He

was one of those who came to our house at Njuyu under cover of night to be

taught, when we were in the early struggles of the work, as has been already

referred to. He and his brother Makara were the first to be baptised in

1890. His father was a witch-doctor, and Mawalera in early years had to

attend him in the ceremonies of his practice, and become “ art and part,”

consciously or unconsciously, in a practice of deceit. He is possessed of an

acute mind, and has always been observant and thoughtful. He is well versed

in native lore, and when a little boy herding the goats in the Lunyangwa

valley witnessed the advent of Dr Laws and Mr Stuart, and the slaughter of

natives conducted about that time by the Chipatulas. He carries a peculiarly

happy countenance, and his merry laugh makes him a favourite with all

classes. From the first his profession of Christianity has been frank and

powerful. Those who know him understand how, in private discussion with the

heathen, and by personal testimony always given humbly and with respect for

his seniors, his influence has been wide and permanently good.

Elangeni station has always been under a native. Mawalera’s

brother, Makara, was placed there by Dr Steele a year before he died. It

also was an experiment and justified itself. The chief of the district,

Maurau, is a brother of the late Mombera, and when the school was opened in

his village Makara was sent there temporarily. So great, however, was his

influence, that Maurau requested that Makara should be sent to reside there

permanently. Ground was given for house and gardens for the teacher, and

Makara removed his family and took up his residence under Maurau, where he

has conducted a most successful educational work, and where his teaching of

the Word has been blessed to the conversion of many. He was the means of

breaking the war-spirit in that district, and one of the first converts was

the eldest son of the chief, who before was a notoriously passionate and

cruel man, and ruled his slaves with an iron hand. His first act was to give

his slaves their freedom, and to pay them for the work they did on his house

and in his gardens. Nawambi, the ferocious war-dancer who is referred to in

the chapter on William Koyi, became a new man, although not a Christian,

under Makara’s influence, and a school has been carried on in his district

also by Makara.

Hora station, as has been stated in a former chapter, was

opened by Mr and Mrs McCallum, and on their being transferred to Mwenzo

station, the work there was also placed in the hands of a native

teacher-evangelist who had been with Mr McCallum both at Ekwendeni and Hora.

Thus, within a short space, we had given up two European workers in

Ngoniland and developed native agency in the manner shown. This we look upon

as a real advance, proving both the permanence of the work among the

natives, and the possibility of speedily evangelising the country by means

of native agents. Africa must be evangelised by the African, and although

our native helpers are only moderately equipped, their work and influence

serve to show that more fully trained agents obtained through the Training

Institution, we may hope for greater results than we now see.

In former days the Ngoni were the troublers of their mission

stations, and it is worth noticing in connection with the transfer of Mr M°Callum

to Mwenzo, how the Ngoni in their new character as peaceful worshippers of

God were able to render assistance to a far - distant mission. Mwenzo

station has lately been begun by Rev. Alexander Dewar. Houses had to be

erected and the station laid out, but the natives of the district were not

eager to help in such work, even although the presence of the Mission was to

be for their protection and benefit. They belong to the Nyamwanga tribe

which was formerly harassed by the Ngoni, many members of the tribe having

been carried captive to Ngoniland. The advent of Mr and Mrs M0Gallum with a

band of loyal Ngoni, some of whom were Church members and catechumens, was

most opportune. The Ngoni were known to the Mwenzo people only as cruel

warriors, constantly raiding their neighbours, but now they saw them in

their midst with the implements of peaceful labour in their hands, and the

Word of God in their hearts, and on their tongues. They aided in the work

which the Mwenzo people declined to do, and at the same time by life and

word, proclaimed the reason of the change in their manner of life. The

effect of this has been very great and a valuable object-lesson in that new

district, saving years of toil before the people could understand fully the

meaning or fruits of the Gospel. Mr McCallum continued his teaching, and had

the joy of seeing several of those who had gone with him admitted into the

visible church by baptism, some time after he settled there. Thus the trial

of having, for the third time, to relinquish an organized station and submit

to the hardships and difficulties of pioneer work, was in some measure

rewarded.

For several months in 1896 we were in considerable anxiety in

connection with a threatened collision between the British Commissioner and

the Ngoni. As recorded, Mombera, the paramount chief, had died, and for some

years the tribe was ruled in sections by the head-men or sub-chiefs. The old

desire of Ng’onomo to increase his power and attain to the chieftainship was

revived. In his district, and that of Mperembe, we had made frequent efforts

to be allowed to begin work but without success. We were hopeful that in all

the other districts the influence of the Gospel was such that war was for

ever at an end, and now our hopes were to be tested by months of turmoil and

excitement. The Mission had been the only outside influence acting in

Ngoniland, and no Government agent had visited the Ngoni officially since

the British Consul saw Mombera in 1885 when friendly greetings were

exchanged. Over all the surrounding tribes in the Protectorate, the

Government had exercised its jurisdiction, and as Mperembe and Ng’onomo had

not given up war and raiding, they spread the report that the Ngoni were

being left alone because the Government was not strong enough to meddle with

them. In this way they strove to revive the old war-spirit throughout the

country, and of course our work, and especially our native helpers, came in

for adverse criticism. The Evangelists in charge of districts had much to

bear, but the Christians rallied to their support, and by calm and judicious

behaviour they quieted many a turmoil and saved their work.

When the country was in that state, an event occurred which

threatened the peace with the British Administration and gave us much

trouble. The district of Kasungu, lying to the south of Ngoniland, had been

the scene of a conflict between the Commissioner’s forces and the natives

there. Chibisa, the chief, made his escape when his town was taken, and came

to Ng’onomo as a refugee. As soon as we knew it we tried to persuade

Ng’onomo to drive him away, lest trouble should come upon himself. Chibisa

pretended to have a considerable army at his command, and tried to incite

Ng’onomo and Mperembe to join him in an attack upon the British at Kasungu,

where the latter had established a fort. Mr Swann, the Government agent at

Kotakota, instead of pursuing Chibisa with an armed force, very judiciously

sent policemen with a letter to us requesting Ng’onomo to hand over Chibisa

to them. Ng’onomo refused. Mr Swann’s intimate knowledge of African natives

made him alive to the danger from the native police, who have too often

overridden their commissions and become breakers rather than guardians of

the peace, and the delicate business he had in hand with such a man as

Ng’onomo. He had no desire to induce a rupture with Ng’onomo, and

wrote: “The police have orders to obey the missionaries, and to come back if

the chiefs allow Chibisa to escape or refuse to arrest him. They are in no

case to do anything but visit the chiefs, take the man from them, and

return". Chibisa subsequently, in alarm, fled to Mpezeni, another Ngoni

chief (mentioned in the first chapter), living nine or ten days’ distant to

the south-west. As Mr Swann’s letter was addressed to the Ngoni chiefs and

required their answer, we convened meetings in different districts to

discuss the situation. We pointed out to them that unless they made their

position clear, they might all be involved in trouble with the Commissioner.

All, save Mperembe, from the first denounced Ng’onomo for receiving Chibisa,

and frequently requested us to head a war-party to go and compel him to

deliver him up. The result of our meetings was, that the chiefs wrote to the

Commissioner saying that since Mombera died there had been no paramount

chief, and each had been simply ruling his own district as before, and could

not be held responsible for Ng’onomo’s conduct, as he was not under either

of them, and they did not sympathise with his action, but desired to live in

peace with the British. Even Mperembe began to see the inadvisability of

continuing in the compact with Ng’onomo, and he also sent a letter to the

Commissioner.

After Chibisa’s flight messengers came from Mpezeni calling

the Ngoni to rise with him and Chibisa against the British. Ng’onomo was the

only chief who could be found to favour the exploit. Many old men had been

eager to accept the invitation, but at the meetings held to discuss the

matter, the young men, and those who had been the flower of the armies, rose

as one man against the proposal to engage in war. Several hundreds were

assembled, some carrying arms, but the result of the meeting was the entire

defeat of the advocates of war. The young men spoke calmly and forcibly,

with every respect shown to their seniors, but they were firm in their

position. The young chief of Elangeni and his cousin from Ekwendeni recalled

how the Gospel had come to them, and how the chiefs and head-men had for

long hindered the work, until in this matter they as a tribe were left far

behind other tribes. The age of war, they declared, must now be considered

as dead. They said they had no desire to point the finger of scorn at their

seniors, but they had apprehended a more excellent way and were to stand

firm in it, and refuse to take the spear again. It was thus demonstrated to

the old men that their voice was no longer a power in the tribe. As we

witnessed their discomfiture, we remembered the time when some of the

notables there had declared that if we got liberty to preach and teach in

the tribe, we would steal the hearts of their people. The result they had

feared they now witnessed. Years before this occurred, another similar

incident was witnessed at Ekwendeni by Mr Stuart. On a Sunday a gathering of

men was convened in the chiefs village to plan a raid on a neighbouring

tribe. When the hour for service came very few people turned out. The

teachers went to the village and rang the bell. All the young men who had

been summoned to hear the plans for war, rose up and left in a body to

attend the service. The old men were left alone, and the war proposals fell

to the ground in consequence.

When the excitement of the foregoing events died away, there

was an increase of interest in our work. The teachers who had been

persecuted were reinstated in public favour, and except for Ng’onomo we were

on friendly terms with all sections of the tribe, as we now had had more

cordial communications with Mperembe. The popularity of our work increased,

and the services were more largely attended, while schools were desired in

places where we had none. The Christian community was consolidated by means

of the trial, and their influence deepened and extended.

In April 1896 Sir Harry Johnston, the Commissioner for

British Central Africa, wrote to us as follows : “You will observe that in

the new Regulations extending the Hut Tax to all parts of the Protectorate,

I have exempted only one district, viz., that portion of the West Nyasa

District which is occupied by the Northern Ngoni. My reasons for doing so

are these:—Hitherto the Ngoni chiefs have shown themselves capable of

managing the affairs of their own country without compelling the

interference of the Administration of the Protectorate. They have maintained

a friendly attitude towards the English and have allowed us to travel and

settle unhindered in and through their country. As long, therefore, as the

Northern Ngoni continue this line of conduct and give us no cause for

interference in their internal affairs, so long, I trust, they may remain

exempt from taxation as they will put us to no expense.” The Ngoni remain to

this day the only tribe not under the direct jurisdiction of the British

Government. They are, however, no less helpful than others in the great task

of the redemption of Africa, which is now so successfully guided by the

Administration of the Protectorate as the temporal head. Apart from labour

given at mission stations, many hundreds of men go every year to the coffee

plantations of the Shire Highlands, and to the trading corporations at work

in various parts of the country, where they prove steady and successful

labourers, without whom, and others, the commercial interests could not

prosper. But let us not forget that all has come about through the preaching

of the Gospel of Christ.

How deeply the Christian element has become fixed in the

tribe was shown at the placing of a paramount chief in room of the late

Mombera in 1897. When the Ngoni found themselves face to face with the

British Administration, and realised the need for a chief, they proceeded to

elect one. To this ceremony all sections of the tribe came. Mperembe,

because he himself desired the chieftainship, had delayed the event, but he

now took an active part in furthering the appointment of Mbalekelwa the

eldest son of Mombera. He sent for Mawalera Tembo at Njuyu, and desired him

to remain throughout the ceremony, as they did not wish to do anything

wrong. It might be said that our teacher-evangelist was the most important

individual there, as he was consulted on every point. He turned the occasion

to good account by conducting religious worship, and subsequently addressing

the assembly on the foundation of good citizenship and good government,

charging the chief to rule his people by the Word of God, and for ever

sheath the sword of his fathers.

But the occasion was not to pass without an attempt being

made by Ng’onomo to raise the war spirit. By violent speeches and war-dances

he called them to observe the customary duty in placing a new chief, viz.,

to send out an army “ to wash their spears in blood.” Mawalera and the other

teachers were assaulted with opprobrious names. They stood their ground and

were supported by most of those assembled, and eventually the ceremonies

ended quietly and happily. Mperembe, in the dim light of his new thoughts of

the Gospel, offered a sacrifice to Mombera’s spirit, praying him to remember

the missionaries when they taught God’s Word to the people!

It was a time of great rejoicing, and one of the first acts

of the chief was to signalize his accession to the throne by requesting that

schools be established in his villages, and he himself desired to become a

pupil of the teacher who was sent. At the same time a sub-chief in the

Ekwendeni district had to be appointed in room of the late Mtwaro, who died

some years before Mombera his brother. The reason for delay in this case was

the confirmed objection to the son of Mtwaro, as he was a teacher in the

Mission and a Church member. But God, who worked in all that was taking

place, gave us the joy of seeing the people, of their own free will, choose

and appoint Amon Jere, not only a Church member and teacher, but an ordained

elder in the Church, to be his father’s successor. At the same time Yohane

Jere, the elder brother of Amon, was elected to the important office of “

Father or adviser of the chiefs,” so that while we never interfered with

their tribal affairs, or put forward any of our pupils to positions of

honour, our work was recognised in these important events.

Just before our departure on furlough in 1887, we welcomed as

colleague the Rev. Donald Fraser, widely known in connection with the

Student Volunteer Missionary Movement. His introduction to the work was at a

time when it was at the height of the flood. The schools had been

successful, the teacher-evangel-ists had been active in diffusing scriptural

knowledge, and we had come to a reaping time. At Ekwendeni, where the

Europeans were located, thirteen men, seven women, and nine children, were

baptized on one Sabbath, while many more were admitted to the catechumen’s

class. On another Sabbath Mr Fraser went with me to Hora station, where five

men, one woman, and four children were baptised, and about forty admitted as

catechumens. But the blessing was not confined to stations where Europeans

were working, for at Njuyu and Elangeni, as at Hora, where our native

assistants were located, there was a season of rejoicing as an abundant

harvest was reaped on two other Sabbaths. I quote the account given by Mr

Stuart who accompanied Mr Eraser to those places.

“On a recent Saturday we left Ekwendeni and spent the Sabbath

at Elangeni. Ten young men, who had been examined at Ekwendeni and given

satisfactory evidence of their faith, were admitted. As it was the first

service of the kind ever held in the district, a great crowd of people

turned out to witness this, to them, strange ceremony. The young son of

their chief was among those baptized.

“In the afternoon we had a quiet little gathering, when

sixteen of us sat down at the Lord’s Table. Makara took part in this

service, giving a very effective address on the love of God in sending the

good news of the Gospel to the Ngoni.

“The following Sunday we spent at Njuyu. For a long time past

a quiet work of grace has been going on here, the extent of it only now

becoming apparent. We arrived on Friday afternoon. We saw as many as we

could that night, and on Saturday we were in a state of siege nearly all

day. Fifty-one persons altogether were examined, and out of these

forty-four— twenty-two men and twenty-two women—were held by the Church as

fit for baptism. Most of these have been for years connected with the

Mission. Some of them received their first instruction in school; some are

the wives of teachers, and have been taught by their husbands. One old widow

is the mother of a teacher. Another woman is the mother of one of the late

Dr Steele’s personal boys, a boy who is now being educated at the

Livingstonia Institution. The father, in this case, is still a heathen. One

young man, a rescued slave, was long ago the servant of the late Mr James

Sutherland. Some are husbands of heathen wives, and others wives of heathen

husbands, and in not a few cases both the husband and wife were admitted.

Some of them in their answers to the questions put to them showed a

wonderful knowledge of divine things. Others again were, according to our

ideas of knowledge, very ignorant; but they all knew that Jesus Christ died

to save them, and are trusting in Him to break the power of sin in their

hearts. Mawalera, whom they all look upon as their spiritual guide, had seen

them all previously, they having come to him of their own accord, and he was

therefore able to give us information about them. We, of course, could only

see to their knowledge, and had to depend largely on the Church as to

whether or not their lives were consistent with their profession. They are

so closely associated together in their village life that every native knows

the kind of life his neighbour leads, and one or two whom we thought right,

as far as knowledge went, were rejected by the Church on account of their

inconsistent lives. Polygamy and beer-drinking are the two great evils. The

former and drunkenness have always excluded from membership, but total

abstinence was not always a sine qua non. Now, however, the Church at Njuyu,

having realised the dangers of example, has resolved to eschew the beer

entirely. Coming thus from themselves, it is far better than if it had come

from us. Reformation and not revolution will make them intelligent

Christians.

The Sabbath was a great day, and will long be remembered in

the history of the Church at Njuyu. In the forenoon we had the baptismal

service, and also the ordination of four elders, the first to be set apart

at Njuyu for the office Mawalera, Makara, and two others having been chosen

by the Church. The choice shows the sound sense of the members.

“During the afternoon we observed the Communion, when about

eighty of us partook of the Lord’s Supper. The service was most impressive ;

simple, perhaps, there being an absence of fine surroundings and priestly

garments, and the people, most of them, rude and ignorant. The worshippers,

at least, were devout and earnest. At this service Mawalera delivered a most

impressive address, when one woman could not help interjecting a remark by

way of emphasis. The brotherliness existing between the, Church members and

the heartiness manifested at all the services were marked. Mawelera has an

important work before him in teaching these converts, but we have confidence

in him. ‘The Lord hath done great things for us; whereof we are glad.’”

Thus on four successive Sabbaths in Ngoniland, eighty adults

were admitted to the membership of the Church, while several hundreds on

profession of their faith were enrolled as catechumens.

Under Mr Fraser and Mr Stuart with their native helpers, the

work has been greatly extended and blessed since then. They have recently*

had the satisfaction of seeing the last of the doors in Ngoniland opened to

the work of the Mission. That arch-enemy of peace, Ng’onomo, has signified

his change by receiving teachers, and Mperembe too has not only received

teachers, but has become a liberal supporter of the work by gifts of stock

at the monthly collections. Owing to the spreading out of the villages and

removals to new ground, the number of the schools has been increased, so

that sometimes as many as four thousand scholars are under instruction, and

now school fees are being charged. Ten years before, our first school with

twenty-two scholars was opened. Although that may for a time diminish the

attendance, the wisdom of the step will be seen. The minimum of attainment

with which we are satisfied in the case of most of those attending, is that

they leave the school able to read the Word of God for themselves, and

possessing a copy of it. While thousands of copies of school books have been

bought by the people, there is a widespread desire to possess the

Scriptures. Hundreds of Zulu Bibles, Testaments and single gospels,

hymn-books and catechisms, have been sold, amounting to a large sum. The

people who were wont to steal rather than work to acquire anything, now give

a month’s labour for a copy of the Bible, or a fortnight’s for a copy of the

New Testament. Men with the marks of old battles on their bodies, may be

seen earnestly labouring at what once was considered ignoble work, in order

to own a copy of the precious Word of God. The liberality of the Christians

is remarkable.

There is little trading with outsiders in Ngoniland, and

their means of acquiring wealth, with wages at a penny a day, are small, yet

the value of several pounds is frequently given as a church-door collection.

Besides this the people are undertaking the support of schools for their

children, and altogether it is seen to be true as Mr Fraser wrote some

months ago, “The work here has entered on a new chapter.” In another letter

he says on this point, “The monthly collections are moving on apace. Mr

Stuart and I have turned into grain and iron merchants, and our back-yards

are huge poultry establishments. Mr Stuart takes fowls for books, and about

120 fowls were received last week alone. The Sunday collections are a rare

sight. No less than 150 carriers brought in the offerings from the

out-stations. My house and verandah are packed with the produce, and the

baskets, and the hoes, and the beads which the people gave. Two bulls, a

cow, and two goats which were contributed were bought up at once. Every

month sees a visible increase in the liberality of the people. Then as to

books. I fancy that at this station alone quite 1000 volumes have been sold

in the last eight months.”

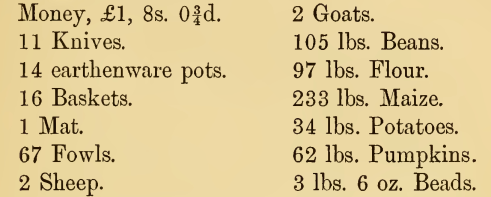

At the Communion Service held at Ekwendeni in May 1898, to

which the following accounts refer, the offering of the people for the

service of God was as follows :—

The total value, not including European contributions,

was £3, 3s. 5½d.

An intelligent young man of the tribe of Tonga, describing

the services to a companion, said he stood at Ekwendeni and saw band after

band coming over the distant ridges, and steadily marching towards the

Mission station, where they were gladly received by the Christians, and

taken away to the villages to be entertained. The villages were crowded with

guests, men in some, women in others, and there seemed room for no more.

Still, however, other bands appeared on the horizon, and as they arrived,

the warmth of Christian feeling made elastic the possibilities of

hospitality. “As I saw this,” he said, “I marvelled.” “Then the services,

where, with an elder or other leading Christian, small companies gathered by

themselves for prayer, and many were melted to tears—as I saw these I

greatly marvelled.” “Then at the baptismal service, as I saw those who were

to be baptised coming forward one by one, and receiving the rite until Mr

Fraser’s arm grew tired, and he sat down, and Mr Henderson continued- in his

place; as I saw men with scars of spears and clubs and bullets on them; and

as I saw Impangela, the widow of Chipatula, baptized, I marvelled

exceedingly. I said in my heart,

‘Can these be the Ngoni submitting to God, the Ngoni who used

to murder us, the Ngoni who killed the Henga, the Bisa, and other tribes?’

And then at the Lord’s Table, to see these people sitting there in the still

quiet of God’s presence, my heart was full of wonder at the great things God

had done.”

The Rev. James Henderson, of the Training Institution, has,

on request, furnished the following account of the Communion Season at

Ekwendeni:—

“I was travelling up the Lake shore on my way back to

Livingstonia after conducting the Sacramental Services at Bandawe, when I

got a letter from Mr Donald Fraser, asking me to turn aside and go up to

Ekwendeni to assist him with the Sacraments there. I had left Livingstonia

for the work at Bandawe on the day when the schools were closed, and now

there was little more than a fortnight remaining of the vacation, and the

work for the new session was all to *be prepared. With the heat and the

rain, the fever, the trudging through the loose sand, the constant moving

from place to place, and especially after the excitement and strain of the

last great week at Bandawe, I was as tired as could be, and my inclination

was to pass on and choose the first deserted bay for a camp, where, for a

few days, I might cease to be a missionary or any other sort of thinking

animal. But Saturday afternoon found us striking inland across the mountains

for Ekwendeni, and spending Sunday among the Tumbuka people on the uplands.

I reached the station on Monday evening. I can never be too thankful that I

did not miss seeing, and that I was privileged to take some small .part in,

this remarkable sacramental gathering.

“The meetings were to begin in the week after I arrived. Mr

Fraser had decided to have things very much on the general lines they used

to follow at a Communion Season in the Scottish Highlands. The examination

of catechumens seeking to go forward to baptism was finished, and it was

known how unprecedentedly large was the number to be admitted. It was felt

on all hands that this would be a great opportunity for reaching the hearts

of those that had hitherto held aloof. For some time the native Christians

had been assembling daily for prayer, and now they were looking forward to a

time of great spiritual awakening and quickening. The missionaries were

expecting more than that. It would be a gathering of the whole Christian

Church of the tribe, and the missionaries trusted that the Church as a body

might be led to make a further forward step in spiritual experience. They

looked away to the untouched regions beyond, and they were praying for an

outpouring of the Spirit that there might be fuller consecration to the

Lord, and new devotion and enthusiasm for His service.

“Of course there was no building at all adequate for the

expected congregations. A temporarary open-air church had to be set up. That

is not difficult in Africa. Posts, split branches, and the strong, tall

grass, provided a screened enclosure—protection from the wind is what is

required—and some bricks and a few planks make all that is needed for a

platform. Seats can be dispensed with on such occasions. They are ornamental

rather than necessary.

“On Monday the people began to assemble. The first comers

were from Mperembe’s, the raiding chief who had only very lately received

teachers. They had brought a contribution in the shape of a sheep and a goat

from the chief himself, and their appearance was a picture of Mperembe’s

attitude to the Mission. They were evidently intended to make up by numbers

what they lacked in age and status, and were altogether a non-committal

deputation, raw and rustic, and a good deal ‘out of it’ when the other

peoples gathered. By Tuesday evening the footpaths were full. Whole families

were coming, the mothers and daughters carrying cooking-pots on their heads

and bags of flour, the men with strings of maize cobs on their shoulders and

other produce of their gardens for the ‘ collection/ and often a tired child

on their backs. Most of them were dressed in snowy white calico. They

travelled silently; and the people in the heathen villages by the way

climbed up the ant-hills to look at them, and called, so they told us, ‘

What has happened 1 What impi is after you ?5 Past the old houses of the

first Ekwendeni station, across the rising ground, we could see them coming

in a long straggling Indian file, which changed into solid masses as they

crossed the river and came up the Mission road. It was then that I realised

the nature of the work that was being done among the tribe. The swinging

pace could not be mistaken, even before the individuals could be seen. It

was the fighting men, the men in the prime of their strength that the Gospel

had laid hold of. A fitter-looking set of men and women it would be hard to

find anywhere. What a promise they are of the speedy coming of the Kingdom

of Christ in that land. All Wednesday forenoon they streamed in, people that

had come from far, and slept one or two nights on the way.

“The enclosure was intended to hold somewhat over a thousand,

but it was soon evident that an extension of it had to be made. The

'hospitality committee,’ the directors of which were the two local chiefs,

Yohane and Amon, had their resources taxed to the utmost. Every hut in the

neighbouring villages was taken over by them, and when these were filled

they made use of the cattle kraals. There was no trouble made about it. I

heard that when Yohane was asked first how many people he could accommodate,

he thought he might manage with a hundred, but when the need arose he

himself arranged for over a thousand.

“On Wednesday at mid-day the first meeting was held. Well on

to 3000 people were present. They had taken their places many of them

long-before the hour, and when we went down they were singing a hymn.

Exuberance of spirits is the characteristic of this Church, and the singing

is something always to be remembered, but the meeting had not gone far on

before it became clear that it was not the familiar mood of the people that

had to be dealt with. They were so bent on hearing that they altogether

forgot their correct listening manners, somewhat ostentatious in attention,

and sat up, looking straight at the speaker. They had evidently made up

their minds that they were to learn something. The solemnity of the

consciousness of the presence of the Lord seemed to creep over the whole

assembly. I confess that as I sat and listened, while Mr Fraser and Mr

Stuart addressed the people, touching them and swaying them with their

words, something like fear came over me, and -I doubted whereunto this would

grow. Would excitement seize the people, and could it be controlled? That

day I prayed far more that no evil might befall the gathering than that good

might come. But my fear was foolish. The thing was of the Lord. It was in

His hands.

“Most of the addresses were intended for the believers, and

dealt much with heart-sinfulness. The touch-stone of self-examination

proposed was conscious daily communion with the living Christ. The addresses

were pointedly practical, calling for definite acts of self-surrender to the

Lord. Men and women were entreated to deal with their Saviour about the

things which they found standing between Him and them. The person and work

of the Holy Spirit were brought prominently forward.

“The opening day, as might be expected, was one of

perplexity. The Christians had thought, perhaps, that the meetings were

intended almost wholly for those outside, and they found that it was

themselves that were addressed. Their selfexamination brought with it sorrow

and humiliation. The meetings after that took a new tone. There was more

stillness and less self-certainty. The Christians were seeking God again,

and striving with the chains of self and the world.

“One night the teachers asked Mr Fraser and myself to meet

with them in the house where they were staying to explain to them

difficulties, mostly with reference to the work of the Spirit, which were

troubling them. Mr Fraser had been with them alone the previous night. We

sat on the ground along the walls, dim fires burning on the floor down the

middle of the long building. There was no formal teaching or speaking. In

the semi-darkness the men talked with the utmost frankness; and there was a

time of confession and prayer. Several of the older men gave signs of having

been brought very near to God. Coming outside we found the air full of

hymns. A tropical moon was full in the sky, and in the villages all around

the people were met out of doors singing, and as the soft breeze rose and

fell the words were borne to our ears. The Evening Prayers were long over;

but the hearts of the people were too full for rest.

“In the middle of Friday night an incident occurred which

might have been attended with evil consequences among a people naturally

superstitious. A little child, brought by its parents to be baptised, they

themselves also being at the same time admitted into the Church, was taken

ill; the journey had been too much for it. They came with it to us for

treatment, when it was far too late, and as we were looking at it, it died.

It was a heavy trial to them. I think it was their only child. They were

away from home and none of the usual customs of honouring the dead could be

observed. But they took the situation bravely. They made no noisy

lamentation. All night they sat alone beside the little body in one of the

Mission rooms, and, when the morning Prayer Meeting was over, with a company

of friends they carried it forth to burial. It was laid in the little plot

where the remains of Dr Steele lie at rest. And the great congregation

looked down the slope, and many of them wondered for they were seeing a

Christian burial for the first time. We were singing a hymn. There was no

wild weeping and wailing. And from the side of the grave were borne to them

the triumphant words in which the Christian proclaims his faith in the

resurrection, ‘ Death is swallowed up in victory. 0 death where is thy

sting? 0 grave where is thy victory? . . . Thanks be to Cod which giveth us

the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.’ Cod made death even to work for

our good. It was a lesson without which the other teaching would have hardly

been complete.

“The second service of Saturday was the meeting in which most

interest centred. The congregation, which had been growing larger every day,

was now almost at its greatest. Every corner of the enclosure was filled. In

the centre sat the men and women to be baptised. The native elders arranged

them according to their districts. They were in all 195 adults. Again I was

struck with their appearance. They were the pick of the people in the prime

of life. Such a sight was never before seen among us, and rarely in the

whole history of the spread of our Faith. Oftener than once the head that

was bowed before us, as they came forward to receive the rite, was scarred

with an old wound; for several of those baptised had taken part in the very

last raid of this section of their tribe. It was a wonderful day of

ingathering that we were privileged to see, and we were but lately come into

the field.

Some of the early sowers could only hear tell of it, and

others—Koyi, Sutherland and Steele —were with their God. The day was of the

Lord. We were as onlookers upon His doings. It was natural that He should do

great things.

“The celebration of the Lord’s Supper was held upon the

Sabbath forenoon, when the congregation amounted to nearly 4000. The

enclosure was packed to its utmost capacity. On a large ant-hill outside a

crowd of curious sight-seers assembled, grey-bearded old men, Zulu ndunas with

the ring of hair crowns, and skin - clad heathen from the remoter villages,

and around the fence stood hundreds of miserable - looking Tumbuka women,

craning red-ochred heads over the grass to watch the proceedings. The

addresses were calls to action. If the Lord had done anything for His people

in the course of the meetings they were now to let it appear in the vows

which they renewed before Him. Seated in rows in front and on each side of

the platform the Church members formed a large body, but the greater mass of

the people was still beyond the separating space. What was true of this

assembly was true, on a greater scale of disproportion, of the land. The

Gospel had as yet come only to the few, and the few must bear it to the

many. The King was present at His feast, and He was entering into the full

possession of many subjects. In His presence anxiety was giving way to

peace. In His keeping the future could be faced with joy. Never was such a

collection taken in the land before. A heap of Indian corn nearly breast

high all but blocked the side entrances. They had given of all kinds of

their possessions, money, beads, rings, bracelets, knives, hoes, axes, pots,

baskets, mats, pumpkins, millet, beans, potatoes, fowls, sheep, goats, and

cattle.

“In the afternoon the children were brought for baptism, 89

in all, thus making a total of 284 souls received at the one time into the

Church.

“The feast was now over; the time for work had come. At dawn

the next morning we met for the last time to give thanks. By mid-day we were

scattered along every outward path, and some knew that they were not, and

might never more, be alone, for they had learned to walk in conscious

fellowship with the Comforter, the Holy Spirit.”

“It is the Lord’s doing and is wondrous in our eyes.

“Amen: Blessing, and glory, and wisdom, and thanksgiving, and

honour, and power, and might, be unto our God for ever and ever. Amen.” |