|

ABOUT the time when I was beginning to realise how actual

mission work differed from the romantic ideas of it too commonly entertained

at home, and overcharged with which many enter the field, a notable

missionary—A. M. Mackay—far away in Uganda was writing these words:—“Current

ideas at home as to mission work are, I fear, very different; but I have not

heard of any part of Africa, east or west, where the native bearing to the

Missions is different from what it is in this neighbourhood. It is a system

of beggary from beginning to end, and too often of suspicion, and more or

less hostility too. Only when these first adverse stages are passed can we

expect to do any real good. Disarming suspicion and securing friendship are

a slow process, but an absolutely necessary one. They are most wearisome and

trying to the faith and temper of those engaged in the task, while they

yield no returns to show in mission reports; yet on their success depends

the future of our work. Hereabout we are so far from the reaping stage, that

we can scarcely be said to besowing. We are merely clearing the ground, and

cutting down the natural growth of suspicion and jealousy, and clearing out

the hard stones of ignorance and superstition. Only after the ground is thus

in some measure prepared and broken up, can we cast in the seed with hope of

a harvest in God’s good time.”

These are words of truth and soberness, as every real worker

can testify from his own experience. At this time, being unable to move

about among the villages with any degree of freedom, we were often compelled

to pass the time on the station, and were assailed by overbearing and

impudent men and women, clamouring for whatever they saw with us which they

coveted. To say we were annoyed is to use a mild term for our experience.

From morning till night the house was beset by natives begging. They allowed

us no privacy, and our rooms were darkened by a crowd pressing round the

windows and flattening their noses against the panes. If one ventured out

his steps were dogged by a clamouring mob. Any attempt to divert their

attention from begging by showing pictures, explaining the working of

apparatus, or manufacture of articles, was treated with indifference. Time

was of no value to them, and so for many a long day the vicinity of our

house was the meeting-place of all who sought diversion through watching the

white man, or begging for the clothes off his back. Men who could have been

well clothed appeared in rags, which they took pains to show. Others would

come in a nude state, hoping to appeal to us thereby. When they wanted cloth

and beads they complained of hunger, which they indicated by drawing

themselves in and simulating an empty stomach. If one offered them food they

disdainfully rejected it, and explained that their hunger was for calico.

Their importunity and arrogance were at times almost maddening, and

sometimes the only relief got was by shutting up the house and going away to

spend a few hours on Njuyu mountain and leaving them alone. We could not

reason them out of their begging habits. They could not entertain our view

of the disgraceful and undignified habit. They would say in flattering

terms, “We are praising you by begging. Do men beg from people who are poor

and mean?”

But while the annoyance was great, their unreasonableness and

selfishness made it well-nigh impossible to bring any sort of benefit within

their reach. When we began to make bricks for housebuilding, and were

thereby able to put some cloth in circulation among them, the work was

repeatedly stopped by some head-man or combination of natives, who desired

that they only should have the benefit of it. The very people who had been

the friends of the Mission at first became our enemies, and did all in their

power to compel us to submit to their demands to supply them with whatever

they wanted. They had given up the spear and had been coming to our Sunday

service, but as we would not enrich them with earthly possessions they

turned against us, and reviled us for having cheated them, as they were now

poorer than when they followed their own ways. Three brothers, Chisevi,

Injomane and Baruke, the heads of the neighbouring villages, became openly

hostile and threatened to go to Bandawe with war, because we would not pay

them for being at peace with us. Injomane—the murderer of his own mother,

cruel and treacherous—set out and attacked a village near Bandawe. On his

return the war-party made a demonstration at the station, by engaging in

war-dances, and speaking against the Mission and the “news.” The effect of

these war-parties going out was that we were left without mails and supplies

at times, as the Tonga at Bandawe, on whom we had to depend for carriers,

were afraid to venture on the road.

From the native point of view, those members of the Chipatula

clan who had befriended the Mission, and had been the means of our gaining

an entrance to the country, were right in attributing their position to

their friendship for us. They were the sons of a once powerful chief who had

lost his kingdom. They hoped that through the Mission they might regain

their former position. They had heard and accepted Dr Laws’s statement, that

by serving God they would attain to greater riches than by using the spear.

They did not apprehend the spiritual aspect of the case and gave expression

to the only need they felt. Their expectations had been disappointed and

they had, in befriending the Mission, become to a certain extent outcasts

from the Ngoni who were all along opposed to the settlement of the Mission.

They had not learned to work and now that their spears brought them nothing,

they were indeed poorer in all that they valued. It was often a trying

situation to meet their attacks and to quiet their feelings, and in it all

we saw how not the words of man but the Divine Spirit, can reveal to men

their spiritual state and make plain to them the Word of Life. It was

peculiarly hard on William Koyi, when alone among them, to hear the Gospel

accused in this way, and with a better intention than judgment he made

presents to them to keep them quiet. He was discovering that it was an

unsafe kind of peace which was thus produced, and when I arrived the whole

question was discussed. We resolved that such a practice must be stopped.

As time went on matters did not improve. When our

determination not to pay anyone for coming to hear the Word preached, or to

give presents in answer to the demand of those who came to beg, became

evident to them, they used other methods in trying to coerce us. Our cattle

were stolen from the herds when feeding, or from the fold at night, and we

were never able to detect the thief. Trees brought in for firewood or

housebuilding disappeared; clothing hung out to dry was stolen, and our

fields and gardens cleared of produce. As we were living among them on

sufferance, there was no healthy sentiment to which w'e could appeal when

wrong was done to us. If we could not detain the thief in the very act there

was no case. During the rainy season we frequently suffered from

cattle-stealing. On a night when rain was falling heavily, the fold would be

entered and the best beast taken out and driven far away before morning, the

heavy rain obliterating all trace of the route taken. The time of service or

prayer-meeting was chosen for entering the corn-field and garden, and

stripping them of our food supply. It would have been very easy at any time

to produce a rupture between us and the natives by a want of forbearance on

our part, and yet there were circumstances at times, in which it was

impossible not to defend our property though not by force of arms. On their

part they made war demonstrations on the slightest occasion. The cattle-herd

may have allowed our cattle to stray into a native’s garden, and he and his

friends would come to the station armed and perform a war-dance as a

preliminary to opening the case. Nothing was so effectual in overpowering

them on such occasions as quietly to allow them to dance till they were

satisfied, and then calmly say “Good morning.” When the season for

beer-feasts came round we had to live through much that was exceedingly

trying to flesh and blood, and could only be endured for the Lord’s sake.

The beer, which was brewed from a kind of millet, was considered “ripe”

after so many hours’ fermentation, and in order to annoy us it was

frequently made so as to mature on Sabbath. Then early in the morning the

guns would be fired or a horn blown to inaugurate what would be a day’s

debauch, and the people congregated for the orgie. As the hours wore on and

the drunken natives began to dance and sing, the sacred day was filled by

unhallowed sounds, while towards evening what had begun as friendly song and

repartee, ended often in fighting and bloodshed. Our quiet was not only

broken by these sounds from the villages, but sometimes a band of drunken

youths, or men and women, would come to the service or to our door and

assail us wdth foul song and epithet, or engage menacingly in war-dances.

In July 1885 an attempt was made by Injo-mane (before

mentioned) to frighten us into resiling from our position on the question of

presents, and the issue of which considerably strengthened our hands. A

party of Tonga had come up from Bandawe with letters and goods. When they

had gone a few miles on their return journey, Injomane and a party of his

young men attacked them. They were robbed of all their clothing and their

weapons, and some of them wounded. Chisevi, a brother of Injomane, came to

the station and informed us of the threatened attack, hinting that while he

had a good heart to us himself, he had, for the sake of his position, to

appear at times as our enemy, and that we would no doubt see how he esteemed

us and reward him for informing us. Before we had time to act for the

protection of our Tonga carriers, one of them who had escaped without wound

returned to give us information. The others, wounded and robbed, escaped

into the bush, not daring to come back through the villages in a nude state.

We considered that the case should be taken to the chief, in order that we

might see of what value were the words of the chief and councillors in

protecting us. Mr Koyi and I thereupon went to Mombera and made complaint,

pointing out that protection to us must mean also protection to any in our

service. Mombera, with his natural shrewdness, asked us why those who had

brought us into the country had now turned against us. We said that they

were harassing us because we would not satisfy their demands for cloth and

beads. He was very angry and called the Chipatulas “rats,” saying that it

was only our presence that preserved them from the attack of his army. He

desired to send an army over to punish them, but we proposed that he should

send a councillor to make an investigation and call the people together to

inform them that we must be protected.

Ng’onomo, his prime minister, being the councillor for the

district in which we lived, was sent to hold a court. All the villagers were

called up, and although Injomane and Chisevi (who had informed us) denied

all knowledge of the affair, after a whole day’s talk, Ng’onomo decided that

Injomane had done wrong and that the cloth and spears should be returned. We

were asked if the punishment was full enough, and we had opportunity of

expressing our regret that the people in whose interests we had come should

not admit us to their friendship, and permit us to carry on our work for

their good. After warning the people against annoying us, Ng’onomo declared

the indaba at an end. An ox was killed, and the judge, prosecutor, and

defendants all feasted together in amity. The Chipatulas had feared other

treatment, as they had sent away all their herds and goods, so that they had

another exhibition of our forbearance and desire to do them good.

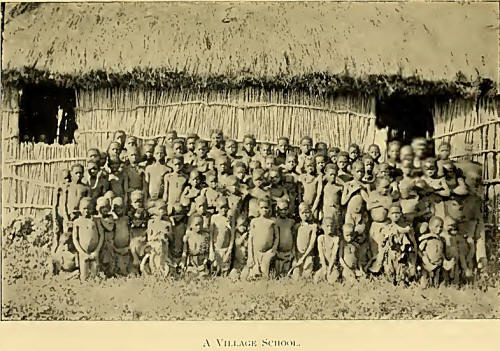

If we had been asked by carping critics at this time, “What

are the results of your work?” we could not have pointed to a single

convert, although the Mission had been already three years in the district.

To all appearance it was a failure. From the chief and the councillors we

had stolid indifference, and direct veto against educating the children, or

moving about to preach the Gospel; and from many of our near neighbours we

were receiving marks of base ingratitude and opposition. But was no work

being done and no good being accomplished? Of stated work there was not

much. We were denied access to every village save two outside the area of

Hoho, as the district in which we lived was called. On the station we were

meeting daily with men and women, and youths and maidens, who were employed

in housebuilding. To these we had opportunity of speaking about spiritual

things. There were the boys in the house as servants who were collected for

worship and oral instruction every day. A few young men outside began to

take an interest in these services and attended. From them grew a stated

service on the Sabbath, to which by and by others came, and although open

preaching of the Word had been proscribed, we gradually came out more boldly

and our service was tolerated, and in turn became an object of interest to

others abroad. Only a few of the women came, and the men were fully armed.

The service was often very uproarious. The dogs snarled and

fought with each other, and when this took place the “ backers ” of the

different dogs whistled and encouraged them. Often audible remarks followed

the reading of passages or parts of the address. Sometimes a man would get

up and declare that it was all lies, and demand cloth as they had heard

enough of the Gospel. Some came out of curiosity; others came having the

impression that we gave cloth to all who attended; and sometimes spies were

sent by the chief’s councillors to see and report what was done. This was

known to us for some time, but we did not think any evil would come of it,

until the rumour got abroad that we were inciting the slaves to revolt

against their masters. Mr Koyi had the burden of anxiety for he heard all

that was being said, and was always either the preacher or interpreter, as I

had not then acquired the language. The rumour arose from the Tumbuka

slaves having begun to attend the meetings, and afterwards discussing the

teaching of the ten commandments in the villages. Their masters began to be

suspicious, and for a time we feared that our service would be stopped. “

The common people heard us gladly,” and were realising that in the Gospel

there were hopes unfolded for them which found a response in their hearts.

We were called to account by the councillors, but were able to satisfy them

as to what was said and done, protesting that we had no desire to interfere

in their tribal relationships or to upset the authority of the chief.

As young men we were used in exercising an influence on the

young men very particularly, and gradually gathered round us a band of half

a dozen, who began to speak in defence of our work. They even met together

for prayer and singing of hymns, and were in consequence marked out for

persecution. They were called “bricks,” in derision, as they worked with us

and favoured us. They were often set upon by others, and had many a hard

day, while yet but imperfectly taught in the Word. But it was the beginning

of fruit, and came to brighten our labours. To show how the changed

behaviour of those lads led them into trouble, the following instance is

given. The child of one of them was ill. Although the grandfather was a

native doctor, the father called me to attend his boy. He was suffering from

croup. It being the custom for the father not to appear in the presence of

his mother-in-law, he could not enter the hut where she was. After treating

the child I went away, but on my next visit I could not find my patient. It

had been carried out into a maize field. I saw the poor thing struggling for

breath, and soon after it died. The “smelling-out” doctor was called to

discover the cause of death. He decided that the spirits were angry, and

wanted to punish the father for forsaking the beliefs of the old people and

listening to our preaching. He had also been neglecting to offer sacrifices

to the ancestral spirits. So strong is their faith in their doctors that all

this was believed, and our young disciple had to suffer persecution.

While the direct evangelistic work was circumscribed, there

was practically no limit to the medical work which I carried on in the

district ruled by Mombera. At first people came in crowds. Those who were

sick expected to be healed immediately, and those who were not sick expected

medicine to keep them well. Many cases of a very trivial nature were

treated, but there was a value in the work apart from the relief given to

the individual. For instance, if a slave were sick and unable to work, no

care was taken of him. Such were sought out, and often a master had a useful

servant restored to his service. He put a value on this, and was favourably

impressed with this part of our work. It was easy to get a hearing from such

as he on the other aspects of our work afterwards. A poor woman, left to die

as an evil-doer if she failed in her “hour of nature’s sorrow,” when saved,

together with her infant, by treatment of the proper kind, would thenceforth

be well disposed towards us and our work. A wife represented so many cattle,

and her husband would appreciate the benefit of our work and be our friend.

Little children, relieved from pain and sickness, understood the practical

nature of the work, and would always respond to our words. In such ways, up

and down the country, the work was quietly and surely influencing the

people, and while there was yet nothing to tabulate for reports, the future

harvest was being insured.

Many things compelled the people to talk of us and our work,

and it was plain that while there was no sign of liberty being given to

teach the children and preach throughout the tribe, the feeling among the

people that we were not being sufficiently trusted was gaining ground. We

took advantage of any opportunity to renew our application to be allowed to

open schools. Sometimes that led to their discussing the question, and at

other times it led to threats to withdraw all permission to preach. We began

to be more respected, as those who had received benefit were bold to declare

it, but we did not seem to have made any impression on the chief and

councillors. They continued to declare that they would never receive the

Word of God, while the common people said that until the heads of the tribe

did so they could not. The reason why the head-men would not countenance our

work was no doubt because they knew that the result of it would be to

overthrow their power over the slaves, and to crush the war spirit in their

children ; also, because they were in the hands of the witch-doctors, whom

they trusted to the utmost as the only channel of communication with the

ancestral spirits. Those witch-doctors were against us as they saw their

craft to be in danger.

One of the greatest effects of the medical mission work was

that, by it, the empiricism of the native doctors was overthrown, and the

common people, ignorant and superstitious, were rescued from the bondage of

their shrewd but deceitful incantations. Native doctors fail in diagnosis

more than in power to heal. Yet in the presence of the majority of diseases

they are helpless, and in that case they fall back on the professed will of

the spirits that the patient is to die.

Towards the end of this year (1885), having received

encouragement from a sister of the chief who was head of a village called

Chinyera, about five miles from the station, we built a round hut there and

Mr Williams went to live in it. When this came to the chiefs ears he sent

for us, and asked if the country had been given over to us that we had begun

to occupy it. We referred him to his sister who had invited us, and we heard

no more of it although it led to increased bitterness among the councillors.

We had thus actually, without formal liberty, opened our first sub-station

and widened the area of our influence. Mr Williams conducted a small service

in his hut, and Mr Koyi remained with me at Njuyu doing the same work. But

during all those months we were the subject of continual discussion among

the people. Sometimes a councillor would spend half a day on the station

speaking on things in general and evidently having some errand which he was

unwilling to reveal. In going away he would ask, “ How long are you going to

stay among us seeing we are refusing your message ? ” What to make of us or

what to do with us, was evidently a problem which they could not solve. They

were no doubt irritated by hearing of the prosperity of their former slaves,

the Tonga, under the Mission at Bandawe. We were considered to be standing

in the way of their compelling their return to bondage, and over and over

again disquieting news of what they were saying and plotting reached us. It

was a common occurrence for a section of the army to be called up for review

and to get secret orders. Not only our own position, but the position of our

brethren at Bandawe gave us anxiety on such occasions. Sometimes the

Chipatulas would suddenly show us great kindness, and inform us that

Mombera’s army was to attack them and us. On several occasions the

neighbours set watch at night and made preparations against being attacked.

Our friends at Bandawe had anxious times too, on our account. Once the

letter-carriers coming up were informed of the expected attack at a village

on the outskirts of the tribe, and in fear returned to Bandawe without

coming near us, and our friends were left in doubt as to our safety.

It was in the end of 1885 that the first expressed evidence

was given that the Gospel was winning its way into any heart. At the close

of the boys’ meeting on a Sunday evening, Mr Koyi had the joy of hearing

from Mawalera, who had been in his employment, that he wanted to pray to

God. After he had poured out his heart in broken accents others joined in

the exercise, asking that God would teach them to pray, and give them hearts

to love and fear Him.

Notwithstanding this new joy and the strength it brought us,

we were soon in deep anxiety on account of the persecution which was

levelled at the youths who had begun to confess Christ among their fellows.

In Matabeleland no sooner did a native confess Christ than the chief ordered

his execution, and at that time we were reading about the burning of

converts at Uganda. We told our young friends these things and asked them to

count the cost. They were not borne up by any unusual emotion, but they

expressed themselves prepared to witness for Christ. The occasion was seized

by Chisevi, one of the Chipa-tula clan (our neighbours already referred to)

as suitable for our overthrow on account of our refusal to enrich them. He

went secretly to Mombera and informed him of what had taken place. Mombera

showed his aversion to the informer and his great friendship for us, by

receiving the report without a word. Afterwards on a visit to the station he

referred to it, and the conduct of the boys was defended by Mr Koyi, and

beyond the persecution which the boys met with, no evil resulted as we

feared might have been the case at the time.

The year had seen our hearts bowed down in sorrow by the

death of our brother Sutherland, whose life and work are referred to at

length in another chapter. We had now at its close the joy of seeing the

ingathering of the first-fruits of the work, in which he was for a time

associated with Messrs Koyi, Williams, and myself, before another cloud was

cast over us by the death of Mr George Rollo, who had just come from

Scotland to begin work at Bandawe. He arrived on Mission duty at Njuyu on

December 21st, suffering from fever, which, with one day’s intermission,

continued till the 28th when he died. As marking the attitude of the people

towards us, when Mombera came to know of his illness he requested us to take

him away lest he should die in their country, and when he died we were

accused of bringing him to the station to die, in order to involve them in

trouble which they ignorantly feared might come to them on account of the

death. They proposed that we should take the body away and bury it at

Bandawe, but eventually a grave was opened near the station, and the

object-lesson of a Christian burial given to the natives, who gathered

together at a distance and looked on. |