|

GLAMIS CASTLE is widely

known as one of the most interesting buildings, both historically and

architecturally, in Scotland. To the lover of Shakespeare, the name of

Glammiss (as it was sometimes spelt) will recall the act of treachery

and murder which tradition gives as having taken place there, when King

Duncan was done to death by the hand or at the instigation of the

ambitious and unscrupulous Lady Macbeth ; although there is no

possibility of proving or testing the truth as to the details or

locality of the tragedy.

To the antiquarian the Castle must be of immense interest, on account of

the great age of the central portion or Keep, which is known to have

been standing in 1016, but "whose birth tradition notes not " ; while to

the romantic and superstitious it is a place where ghosts and spirits

moving silently down winding stairs and dark passages are wont to make

night fearsome. This feeling of eeriness is not confined to the

naturally nervous, for Sir Walter Scott, who spent a night at Glamis in

1704, writes :

" After a very hospitable reception, I was conducted to my apartment in

a distant part of the building. I must own that when I heard door after

door shut, after my conductor had retired, I began to consider myself

too far from the living and somewhat too near the dead."

Additional interest attaches to this Castle from the fact that its

venerable walls enshroud a mysterious something, which has for centuries

baffled the curiosity and investigations of all unauthorised persons :

this secret is known only to three people —the Earl of the time being,

his eldest son, and one other individual whom they think worthy of their

confidence.

Most people have theories upon this subject, and many ridiculous stories

are told ; but so carefully has the mystery been guarded, that no

suspicion of the truth has ever come to light.

One version of the story

is as follows : Several centuries ago Lord Glamis of the time was

entertaining the head of another noble family then resident in Angus;

and in the course of the evening they commenced to play cards. It was

Saturday night, and so intent were they on wagering lands and money on

the issue of the game, that they did not recognise the fact that Sunday

morning was approaching until an old retainer ventured to remind them of

the hour. Whereupon one of the gamblers swore a great oath, with the

tacit approval of the other, that they did not care what day it might

be, but they would finish their game at any cost, even if they went on

playing till Doomsday ! It had struck midnight ere he had finished his

sentence, when there suddenly appeared a stranger dressed in black, who

politely informed their lordships that he would take them at their word

and then vanished. The story goes on to aver that annually on that night

these noblemen, or their spirits meet and play cards in the secret room

of the Castle, and that this will go on till Doomsday. In corroboration

of this story, it is said that on a certain night in the autumn of every

year loud noises are heard and some of the casements of the Castle are

blown open.

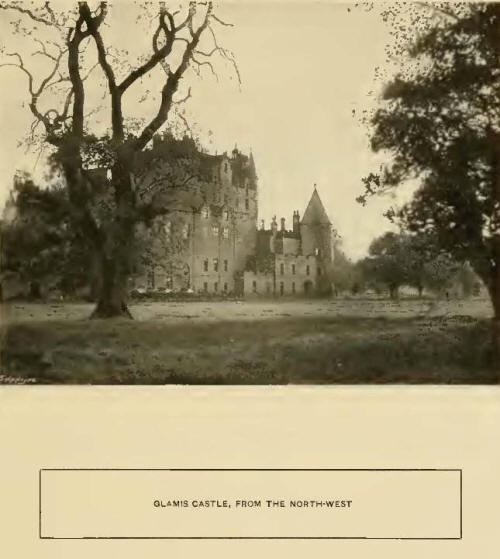

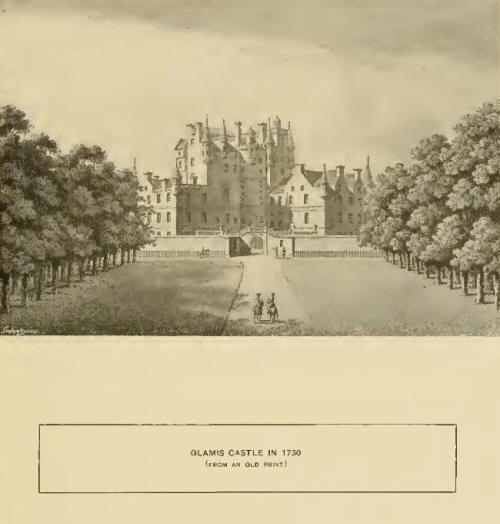

Glamis Castle stands in

the centre of the vale of Strathmore, in a picturesque and well-wooded

part of Forfarshire ; the heather-clad sides of the Sidlaws, which

divide Strathmore from the sea, rising to the south, while away to the

north tower the Grampians, which form a magnificent background to the

ancient pile of buildings whose turrets rise some hundred and fifteen

feet above the level of the ground.

The poet Gray, in a letter, describes the exterior of the Castle in the

following words:

"The house, from the

height of it, the greatness of its mass, the many towers atop, and the

spread of its wings, has really a very singular and striking appearance,

like nothing I ever saw."

The oldest portions of

the Castle are formed of huge irregular blocks of old red sandstone,

which time and weather have mellowed into a beautiful grey-pink colour.

The original Keep was evidently about three or four storeys high, but

Earl Patrick in 1670 heightened it considerably; the extra storeys were,

however, so well " clappit on" (to use the Earl's own words) that it is

impossible to see where the additions commence. The walls of the Castle

in many places are sixteen feet thick, which in the olden days had the

essential recommendation of great security, and also of allowing space

for secret rooms and passages as means of escape in times of peril ;

and, as a matter of fact, two secret staircases have been discovered

within the last five-and-twenty years, and possibly there are others,

which still remain forgotten and unused.

The narrow windows appear

at irregular heights and distances in the central building or Keep and

left wing (the right wing having been burnt down and rebuilt early in

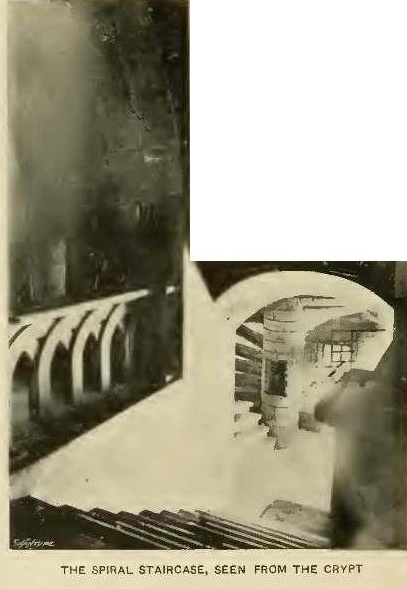

1800 is not so interesting), but the great staircase added by Patrick,

Lord Glamis, in 1605 is very fine, occupying a circular tower, the space

for which has been partly dug out of the old walls of the Keep, and

rises to the third storey. This staircase (the designing of which has

been attributed to Inigo Jones) is spiral with a hollow newel in the

centre, and is composed of stone to the summit. It consists of 141

steps, 6 ft. 10 in. in width, each of one stone.

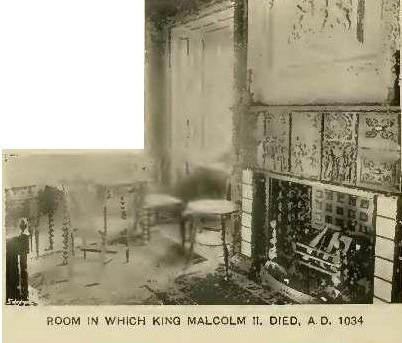

The staircases which were in use before 1600 are very narrow, dark, and

some of them winding, the steps steep and irregular in height, worn into

hollows by the many feet that for centuries climbed them. Up two flights

of these dimly lit, uneven stairs, the wounded king, Malcolm II., after

having been treacherously attacked and mortally wounded by Kenneth V.

and his adherents on the Hunter's Hill, about a mile from the Castle,

was carried by his followers to die in the chamber that still bears the

name of King Malcolm's Room. This murder of King Malcolm is the first

authentic event mentioned by the chroniclers in connection with Glamis.

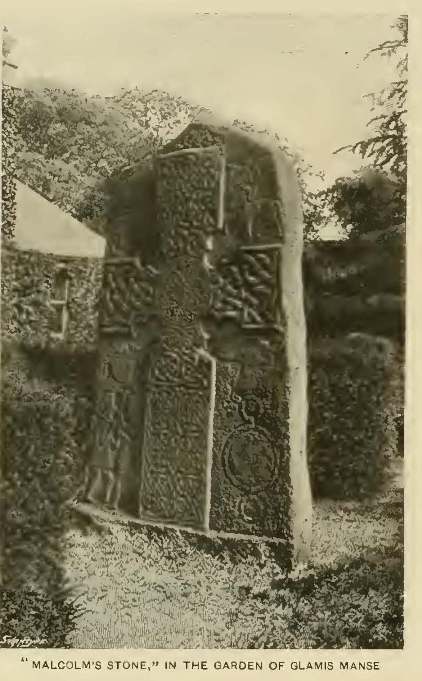

In the parish of Glamis

stand three huge stones of rude design, covered with symbolic

sculptures, which according to tradition were erected to commemorate the

death of Malcolm II. One on the Hunter's Hill is supposed to mark the

spot where he fell, and stands about seven feet high, facing the east; a

cross, figures of men, and various symbols are sculptured on it, but are

much defaced. The stone close to the kirkyard is much larger, and is

called King Malcolm's gravestone, although that king was not buried

there. An ornamental cross and many curious symbols are carved on the

side facing the east; on the other side a fish, a serpent, and a circle

are seen, —symbols of Christianity,— which carvings are of a later date

than the cross, etc., and are attributed to the Knights Templars, who

lived in that part of Scotkind for a long time.

In the time of King Malcolm, Glamis was a royal residence, and remained

so till 1372, when Sir John Lyon, "a young man of very good parts and

qualities, and of a very graceful and comely person, and a great

favourite with the king" (Robert II.), was made Lord High Chamberlain of

Scotland. At that time the King's daughter, the Princess Jean, fell in

love with this young knight, and was given him in marriage, together

with the lands of the thanedom of Glamis, "pro laudabili et fideli

servitio et continuis laboribus," as the charter bears witness, March

18, 1372. Ten years later Sir John fell in a duel with Sir James Lindsay

of Crawford, and was buried at Scone among the kings of Scotland. He

left one son, from whom the present family of Lyon have descended

without a break from father to son to the present day. (It may be

mentioned incidentally that the ancestor of the Lyon family came over

with William I., and that either he or one of his immediate descendants

settled in Perthshire in the district still called Glenlyon.)

Fifty years later, Sir

Patrick Lyon (Sir John's grandson), who was one of the hostages to the

English for the ransom of James 1. from 1424 to 1427, was created Baron

Glamis, and appointed Master of the Household to the King of Scotland.

For the next hundred years nothing of interest occurred, till John,

sixth Lord Glamis, married the beautiful Janet Douglas, granddaughter of

the great Earl of Angus (" Bell-the-Cat "), and died in 1528. Lady

Glamis married, secondly, Archibald Campbell, of Kepneith, whose

relative, another Campbell, fell in love with her. Finding, however,

that his addresses were but ill received by this lady, who was as good

as she was lovely, his love turned to hate, and he revenged himself by

informing the authorities that Lady Glamis, her son Lord Glamis, and

John Lyon, his relative, were conspiring against the life of the king,

James V., by poison or witchcraft. They were tried for high treason, and

wrongfully convicted ! Lady Glamis and her young son were both sentenced

to be burned, and the estate of Glamis was forfeited and annexed to the

Crown by Act of Parliament, December 3, 1540. However, these brutal

judges, on account of the extreme youth of Lord Glamis, feared to bring

him to execution, so the boy was kept in prison, with the death sentence

hanging over him, while the beautiful Lady Glamis was dragged forth and

burned at the stake on the Castle Hill of Edinburgh, July 17, 1537.

Those were days when acts of violence and cruelty were regarded with an

indifference that we cannot now realise, although when she stood up in

her beauty to undergo this fearful sentence, it is recorded that all

heads were bowed in sorrowful sympathy. When this infamous execution was

accomplished, remorse seems to have come over Campbell, who was visited

by visions of his victim looking at him with sad, reproachful eyes.

When, some years later, his death was drawing nigh, he confessed that

his evidence at the trial was altogether false. Lord Glamis was

therefore released from prison, and his estates and honours restored.

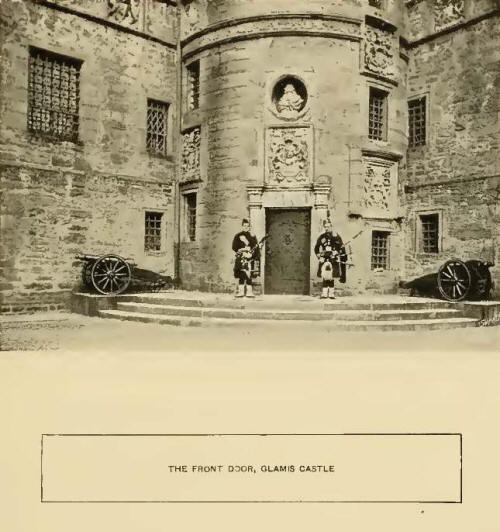

To return to the Castle. The exterior is much ornamented with ancient

armorial bearings in carved stone of the principal Earls since 1606,

quartered with those of their separate wives, among them the Murray,

Panmure, Ogilvey, and Middleton quarterings. Above one window the

initials of Patrick, first Earl of Kinghorne, and of Dame Anna Murray,

his wife, daughter of the first Earl of Tullibardine, are placed, while

a round niche over the front door contains a bust of Earl Patrick, of

whom mention will be made presently. The principal entrance is a

striking feature. The doorway is small and low, and a stout,

iron-clinched oaken door, thickly studded with nails, is guarded on the

inside by a heavily grated iron gate, which opens right on to the great

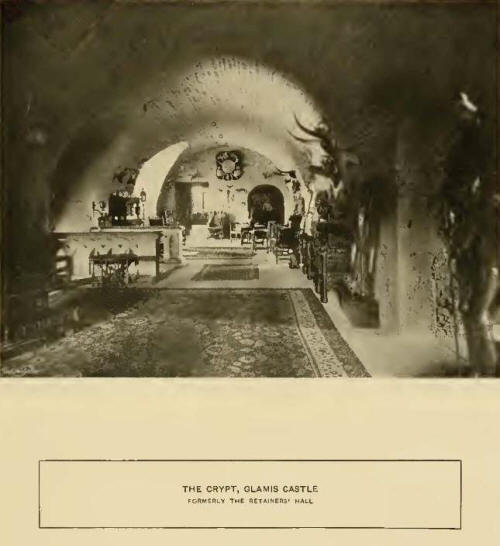

staircase. A flight of steps to the right of the entrance leads down to

the dungeons, vaults, and the old well (now filled up) which supplied

the inmates with water in times of siege ; while another stair to the

left leads up to the Retainers' Hall (or Crypt as it is now called),

low, and fifty feet in length, with walls and arched roof entirely

composed of stone. Of the seven windows, which are small, four or five

are cut out of the thickness of the walls, and make recesses just large

enough to form small rooms, which might have been used as

sleeping-chambers in old days. Lay figures, clad in complete armour,

stand in the recesses, which, especially in the dusk, give an eerie

effect to this part of the Castle. It is said that a ghostly man in

armour walks this floor at night—possibly the original of one of those

armoured figures standing silently in the Crypt year after year, who

may, perchance, have ended his life in the dungeon that lies exactly

underneath. A square stone, now practically immovable, formed the

covering of the hole by which prisoners were lowered into the dungeon

beneath. But there is no doubt that there was also a stair connecting

the hall with the dungeon, which, along with the other old staircases

(some of them have recently been opened out), was walled up at the time

the great new central staircase was built.

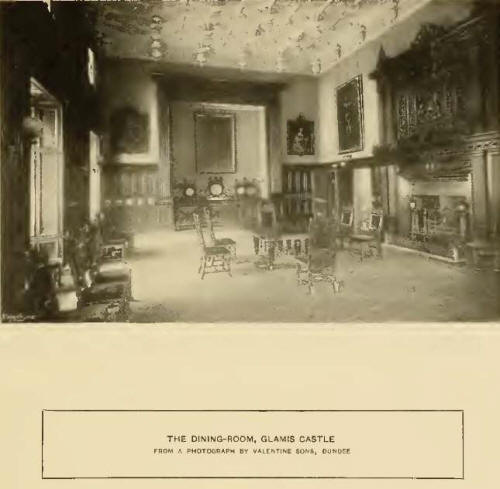

From the south-east

corner of the Crypt a short, dark passage, cut through the stone walls,

leads to the small, quaint, and irregular Duncan's Hall, the traditional

scene of Macbeth's crime, where a year or so ago an old hearth was

discovered built up in the masonry, and has been opened out. The

Dining-room, which is entered from the west end of the Crypt, is another

fine room, though quite modern, having been rebuilt early in 1800. The

walls are panelled in oak, and adorned with some good family pictures ;

but the most interesting object that occasionally appears in it is the

old silver-gilt drinking-cup in the form of a lion, a very ancient piece

of plate, holding about a pint of wine, which in old days each guest was

expected to drain before quitting the Castle. Sir Walter Scott was one

of those who swallowed the contents of the lion, and in a note to

Waverley he says, ''the feat served to suggest the story of the Bear of

Bradwardine."

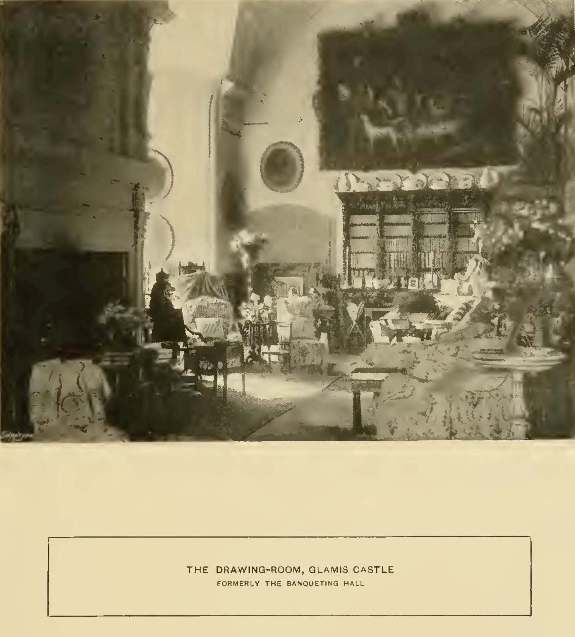

Leaving this floor, with

its dark winding passages, its grated, prison-like windows, and

ascending a side staircase, King Malcolm's room is passed, and the

Banqueting Hall (now used as the Drawing-room) is entered. This room is

a fine specimen of the old baronial days, being sixty feet long by

twenty-two wide, with a coved ceiling of beautifully designed

plaster-work, which was added to the room by Earl John in 1621, whose

initials, with those of his wife, together with the date, are placed at

intervals among the patterns of the mouldings.

The chimneypiece of carved stone is very fine, reaching to the top of

the room, while pictures of the Lyon family, as well as of some of the

Stuart kings and other notables, adorn the walls. Here hangs the

portrait by Sir Peter Lely of the celebrated John Graham of Claverhouse,

Viscount Dundee ; this well-known and distinguished chief, who, had he

lived longer, would probably have restored Scotland to King James II.,

was a great friend of the Lord Strathmore of the time, and consequently

spent many days at Glamis, Claverhouse being situated a bout twelve

miles to the south. The picture represents Dundee as a very handsome

young man, with features soft and refined even to feminine regularity;

but under this gentle exterior can be detected the undaunted and

enterprising valour coupled with the prudence and determination that

were the acknowledged attributes of his character. His coat, a sad

buff-coloured felt, laced with silver, and evidently similar to the one

he was wearing when he met his death at Killiecrankie, is kept as a

valuable relic in the Castle.

What different scenes must this, old Hall have witnessed in its time !

Not many years prior to the visits of the gallant Clavers, the soldiers

of the Commonwealth held their rude orgies under its roof, having been

quartered at Glamis by Cromwell's orders as a piece of petty revenge,

because John, second Earl of Kinghorne, had voted against the delivery

of King Charles 1. To the Parliament. Then in 1715 deep mourning surely

reigned there, when the news arrived that the brave and promising young

Earl of Strathmore had been killed at the battle of Sheriffmuir, after

fighting hard and gallantly in the cause of the Stuarts.

The following year the

mourning was turned to joy when Prince James spent two nights at Glamis

on his way to Scone. What feasting and loyal toasts must have been given

in the Hall in the course of those two snowy nights and days, when the

Chevalier received many of his followers, and gained all hearts by his

princely qualities ! It is said that during this visit eighty-eight beds

were made up in the Castle for the gentlemen in his train. The

Chevalier's bed is still to be seen, though much spoiled by tourists,

who, on certain days, are allowed to go over the Castle ; and the room

he occupied, with a secret stair concealed in the walls, still bears his

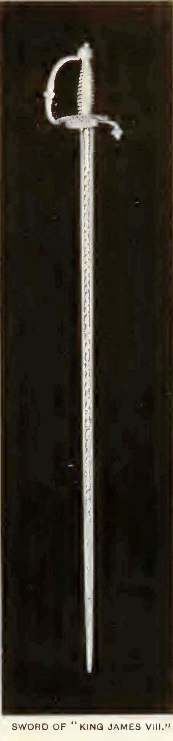

name. His watch and sword are among the treasured curiosities in the

Castle, the former having been found under his pillow after he left for

Dundee. The sword bears the following inscription:

"God save King James 8th:

prosperitie to Scotland and no union. "

But to return to the Hall

itself. The principal picture hangs at the end of the room, and

represents Patrick, first Earl of Strathmore and third of Kinghorne, who

beautified Glamis considerably both within and without, as his diary

testifies, which is in perfect preservation, and well illustrates the

social life of Scotland more than two hundred years ago. In this

portrait he is depicted sitting with three of his sons, pointing with

pride to the Castle in the distance, on which he had spent so much care.

At that time the Castle was surrounded by walled courts, gardens, and a

moat; and the main approach to the south, about a mile in length, was

guarded by seven gates, and was the work of Earl Patrick. These

surroundings were all pulled down early in 1800 by a disciple of

"Capability Brown," the two flanking towers alone being left!

Sir Walter Scott, who revisited Glamis after this barbarous act of

modernising had been accomplished, describes the changes in such

beautiful language that it should be quoted:

"Down went many a trophy

of old magnificence, courtyard, ornamented enclosure, fosse, avenue,

barbican, and every external muniment of battled wall and flanking

tower, out of the midst of which the ancient dome, rising high above all

its characteristic accompaniments, and seemingly girt round by its

appropriate defences, which again circled each other in their different

gradations, looked, as it should, the queen and mistress of the

surrounding country. It was thus that the huge old Tower of Glamis once

showed its lordly head above seven circles of defensive boundaries,

through which the friendly guest was admitted, and at each of which a

suspicious person was unquestionably put to his answer."

There were two or three moats surrounding the Castle, but the)' were

tilled in by Patrick, third Earl of Kinghorne and first Earl of

Strathmore. That Earl proceeds to say of these moats, in his diary,

"which stankt up the water so that the place appeared marish and weat,"

and was generally condemned as "an unholsom seat of a house."

Very close to the walls of the Castle there are the remains of what some

consider to have been a moat, whilst others consider it to have been an

underground passage. It appears hardly wide enough for a moat, and the

fact of the sides being lined and the top beautifully arched with stone

almost favours the supposition that it may be part of that underground

passage of which there has long been a tradition.

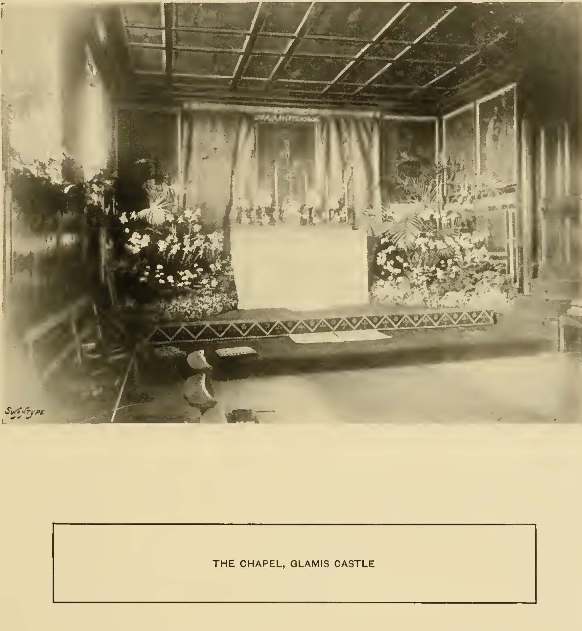

The Chapel, which opens out of the Drawing-room, is one of the most

interesting parts of the Castle. Thirty feet by twenty ; walls and

ceiling are divided into thirty-four panels, each one containing a

picture relating to the life of our Lord and the Twelve Apostles. These

paintings were executed by a Dutch artist named De Witt, whom Earl

Patrick engaged by contract, in 1688, to paint all the Chapel (as well

as a good many ceilings and portraits) for the sum of £90. The contract

for this work is still among the family papers, and is very curious, as

De Witt was evidently a slippery fellow who required a good deal of

binding. When the present Lord Strathmore succeeded to the title in 1800

he found the paintings in perfect preservation, but the Chapel in a

sadly neglected state ; he therefore had it beautifully restored and

rededicated, and daily service has been held there ever since ; the

painted walls and ceiling, stained glass, beautiful embroidered

altar-cloths (worked by the present Lady Strathmore), and flowers,

render this little chapel peculiarly attractive as a place of worship.

The Billiard-room, with

its fine and valuable tapestry, representing incidents in the life of

Nebuchadnezzar, and of which only three examples were known to exist, is

on this same floor, and is the last of the large rooms, being fifty feet

long, but it is not part of the ancient building. Here stands a great

chest filled with beautiful costumes in flowered silks, velvets, and

satins, as well as old uniforms, all belonging to Lyon ancestors of

several centuries ago; besides these a fool's dress remains, cap, bells,

and all complete—a rare possession nowadays. Sometimes these ancient

garments see the light, when the Castle is full of young and merry

guests, who don these slashed and broidered coats and skirts, and when

gathered together in the old Crypt almost seem to have forced back the

hands of the clock of time two or three hundred years.

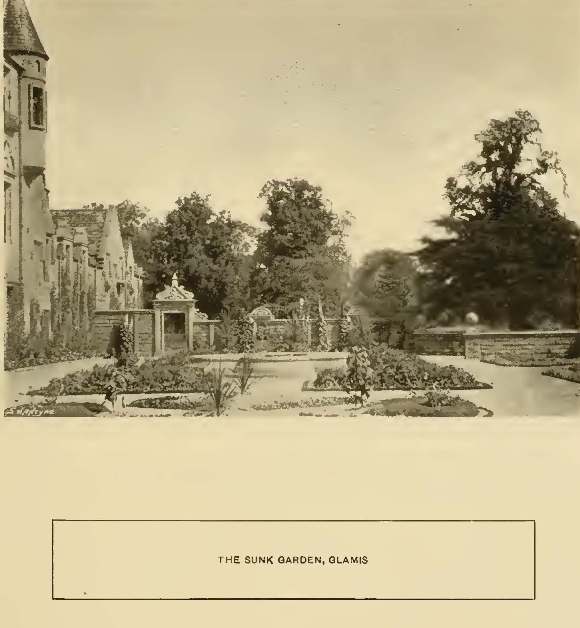

There remains yet much to tell, but space fails. The old kitchen, an

underground vault, dark and low, with one loophole to light it, is a

contrast to the present kitchen, which is fifty feet long and broad in

proportion. The great sun-dial on the lawn is quite unique, bearing as

it does eighty-four dials, supported by four nearly life-size lions in

stone; and although the exact age of this remarkable piece of work is

not known, old pictures of Glamis prove that it was standing in front of

the Castle in 1600. A balustrade of fine seventeenth-century iron work

runs round the top of the Castle, from whence, on clear days,

magnificent views may be obtained of the surrounding country; while the

beautiful gardens, walks, and drives, which have been created by the

present Lord Strathmore (who has bestowed as much care on the old place

as his ancestor, Earl Patrick, of whom mention has been made), deserve

more than passing notice. The old Castle, as it now is, enlivened by the

cheerful surroundings of a large family party, and ringing with the glad

sounds of grandchildren's voices, is a truly pleasant place to live in;

whilst the great iron gate stands hospitably open to welcome the many

guests who pass that way, who, in spite of the Castle's reputation for

ghosts, seem to pass their time merrily enough.

|