|

Preface

The present so

persistently claims our attention that we are in constant danger of

forgetting altogether that past in which it has its roots; and our loss

in so doing is by no means insignificant. Those students of antiquity

who do not allow their interest in the past to blind them to the claims

of the present are continually emphasising the continuity of all life,

and protesting against the habit into which some scholars have fallen of

dealing only with phases of life. This is a protest which cannot be too

often repeated. The heroic days of old are as if they were not, and we

deliberately blind ourselves to every vision which would make us prize

more highly both our heritages and our privileges. There are many ways

by which we may preserve our historical continuity, but hardly any

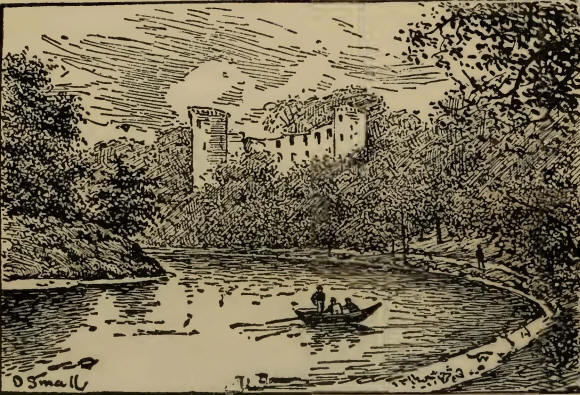

method is likely to be so effectual as purposeful visits to those

ancient castles which remain as silent witnesses of an age that has

passed away.

Happily this method of preserving our touch with the past is as

agreeable to most men as it is effectual. There are few people capable

of resisting the fascination of an old building, especially if that

building has borne a part in some of the best-remembered episodes of a

nation’s history. But, even apart from known historical associations, an

old building, because it is old, possesses an irresistible charm, the

psychology of which Mr. Ruskin analyses in his own inimitable way. “The

greatest glory of a building,” he says, “is not in its stones nor in its

gold. Its glory is in its Age, and in that deep sense of voice-fulness,

of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy, nay, even of approval or

condemnation, which we feel in walls that have long been washed by the

passing waves of humanity. It is in their lasting witness against men,

in their quiet contrast with the transitional character of all things,

in the strength which, through the lapse of seasons and times, and the

decline and birth of dynasties, and the changing of the face of the

earth, and of the limits of the sea, maintains its sculptured

shapeliness for a time insuperable, connects forgotten and following

ages with each other, and half constitutes the identity, as it

concentrates the sympathy, of nations: it is in that golden stain of

time, that we are to look for the real light, and colour, and

preciousness of architecture; and it is not until a building has assumed

this character, till it has been entrusted with the fame, and hallowed

by -the deeds of men, till its walls have been witnesses of suffering,

and its pillars rise out of the shadows of death, that its existence,

more lasting as it is than that of the natural objects of the world

around it, can be gifted with even so much as these possess, of language

and of life.”

Download

The Story of Bothwell Castle here in pdf

format |