|

IT is matter of deep regret that the facts of the

personality and career of Wallace still remain so obscure. There is no

alternative but to piece them together painfully from the strange miscellany

of available materials, perplexed, distorted, fragmentary, and fabulous. Yet

when the misrepresentations of virulent foes and adulatory admirers are

firmly brushed away, the patriot hero stands forth, incontestably, as one of

the grandest figures in history.

On the death of Alexander III., Scotland sank from the

crest of prosperity into the very trough of adversity. The brief reigns of

the infant Margaret and the puppet Balliol only served as breathing-space

for the marshalling of the forces of internal conflict to the profit of a

powerful and remorseless aggressor. Industry was unsettled; commerce was

disorganised. The King was contemned; the nobles were distrusted. Both King

and nobles were liegemen of the foreigner, while the free commons sullenly

nourished the passion of immemorial independence. Scotland was indeed 'stad

in perplexytè.' Her 'gold wes changyd in to lede.' When, and whence, would

ever come succour and remede?

Succour and remede sprang, naturally, from the

insolence and oppression of the minions of the invader. Little did Wallace

know or reck of the solemn farce enacted at Norham and Berwick, or of the

feudal rights of Balliol or another. Like a deliverer of old, 'he went out

unto his brethren, and looked on their burdens'; 'when he saw there was no

man, he slew the Englishman, and hid him in the sand.' An outlaw, he drew to

him friends, free lances, probably enough desperadoes, and waged such

guerrilla warfare as was possible against the oppressors of his family and

his countrymen. Some other knights and squires similarly maintained

themselves in the forests and fastnesses of the land. But there must have

been some distinctive and commanding qualities in the man that was able to

step forward in that dark hour from an obscure social position to lead the

forlorn hope of Scottish independence.

'Wallace's make, as he grew up to manhood,' says

Tytler, 'approached almost to the gigantic; and his personal strength was

superior to the common run of even the strongest men.' Even Burton

dissociates himself from belief in this statement. But surely, though 'the

later romancers and minstrels' have 'profusely trumpeted Wallace's personal

prowess and superhuman strength,' the assertion of Tytler makes no great

draft on one's credulity. On the contrary, in an age when warlike renown

depended so essentially on personal deeds of derring-do, the astonishing

thing—the incredible thing—would be if Wallace had not been a man of

preeminent physical strength and resourcefulness in the use of arms. By what

other means, indeed, could the second son of an obscure knight, a mere youth

just out of his teens, living the life of an outlaw, uncountenanced by the

support of a single great noble, by any possibility have maintained himself,

attracted adherents, impressed the enemy, and become the hero of a nation,

if he did not possess quite exceptional physical strength and prowess? How

is it possible that a man that had gone through the hardships of a desperate

guerrilla, as Wallace must have done, should be other than a man 'of iron

frame'? Ajax was taller than Agamemnon; and Jop may have stood a head higher

than Wallace. But the substantial fact of his impressive physique is not to

be denied. The romancers exaggerate, of course; but on this point even Harry

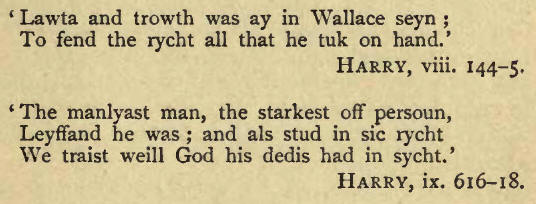

scarcely outdoes Major or Bower.

Harry's slight sketch of Wallace as a 'child' of

eighteen prepares us for the description of his hero in his prime by

'clerks, knights, and heralds' of France, which, he says, Blair set down 'in

Wallace' book.'

'Wallace'

stature, in largeness and in height,

Was judged thus, by such as saw him

right

Both in his armour dight and in undress:

Nine quarters large

he was in length—no less;

Third part his length in shoulders broad was

he,

Right seemly, strong, and handsome for to see;

His limbs were

great, with stalwart pace and sound;

His brows were hard, his arms were

great and round;

His hands right like a palmer's did appear,

Of

manly make, with nails both great and clear;

Proportioned long and fair

was his visage;

Right grave of speech, and able in courage;

Broad

breast and high, with sturdy neck and great,

Lips round, his nose square

and proportionate;

Brown wavy hair, on brows and eyebrows light,

Eyes clear and piercing, like to diamonds bright.

On the left side was

seen below the chin,

By hurt, a wen; his colour was sanguIne.

Wounds, too, he had in many a diverse place,

But fair and well preserved

was aye his face.

Of riches for himself he kept no thing;

Gave as he

won, like Alexander the King.

In time of peace, meek as a maid was he;

Where war approached, the right Hector was he.

To Scots men ever

credence great he gave;

Known enemies could never him deceive.

These

qualities of his were known in France,

Where people held him in good

remembrance.'

It is futile to

dispute over fractional details. Let the most exacting historical critic

array the indisputable facts of Wallace's birth, breeding, and career, and

frame upon these his conception of the figure of the man. It is impossible

that there should be any substantial difference between such a picture and

the picture exhibited by Harry. Fordun states that Wallace was 'wondrously

brave and bold, of goodly mien, and boundless liberality'; and that he ruled

with an iron hand of discipline. Major declines to commit himself to

Wallace's alleged feats of strength; yet he does not scruple to affirm that

'two or even three Englishmen were scarce able to make stand against him,

such was his bodily strength, such also the quickness of his dexterity, and

his indomitable courage,' while 'there was no extreme of cold or heat, or

hunger or of thirst, that he could not bear.' And Bower's description bears

out fully the account given by Harry. The objector is not to be envied in

his task of explaining how Wallace fought in the thickest of the battle, how

he defended the rear against mailed horsemen on barbed chargers, and how he

stood at the head of the Scots in the battle of Stirling Bridge.

But, as Burton justly remarks, 'Wallace's achievements

demanded qualities of a higher order.' Now Burton's cautious reticence gives

especial emphasis to his decided affirmation that Wallace 'was a man of vast

political and military genius.' 'As a soldier,' the circumspect Burton

freely admits, 'Wallace was one of those marvellously gifted men, arising at

long intervals, who can see through the military superstitions of the day,

and organise power out of those elements which the pedantic soldier rejects

as rubbish.' Yes, Wallace had to create, and then to train; not merely to

organise and marshal and order in the field. Wallace started with the sole

equipment of his single sword. With his small and inexperienced body of

comrades, without mailed barons or mailed chargers, he was driven by sheer

necessity to devise means of conserving his force and at the same time

making it as effective as possible in offence. At Stirling, his masterly

selection of the ground practically decided the issue; the rash confidence

of Cressingham only rendered the victory more complete. At Falkirk, as

Burton points out, 'he showed even more of the tactician in the disposal of

his troops where they were compelled to fight'—tactics amply vindicated on

many a modern battlefield. 'The arrangement, save that it was circular

instead of rectangular, was precisely the same as the "square to receive

cavalry" which has baffled and beaten back so many a brilliant army in later

days.' But for the defection of the cavalry, comparatively weak as they

were, Falkirk might have been Stirling Bridge. These tactics, however,

admirable as they are universally, acknowledged to have been, and even

original, were no doubt developed by painful experience in the guerrilla

period. And, on the other hand, it is to be remembered that, while Scotland

had had no experience of war for more than a century, Wallace was not only

crippled by the operation of the feudal allegiance, but had for his

opponents the ablest generals and the most seasoned warriors of the age.

On the moral side of war, Wallace must indeed have

been a sanguinary barbarian if any apology for his seventies be due to the

murderers of his wife, to the conqueror that made Berwick swim in blood, to

the insolent tramplers upon the common human feelings of his countrymen, or

to the juggling reivers of the independence of his country. We decline to

apologise for his alleged private reprisals if you madden a man with open

injustice and intolerable oppression, if you gaily lacerate his soul in his

physical helplessness, it is you yourself that invite him to have recourse

to the primal code of retaliation. If Wallace, as Harry says, never spared

any Englishman 'that able was to war,' it was an intelligible principle in

the dire circumstances of the time; and he is not known to have deprecated

the application of the principle to himself. If he imagined that there had

come to him an admonition, divine and imperative, to slay and spare not, we

decline to censure him because he hewed his enemies in pieces before the

Lord.

Yet such deliberate and

inexorable rigour of policy is a wholly different matter from gratuitous

cruelty. Wallace did not war on women, priests, or other 'weak folk.' It is

not the strong man that is a cruel man. True, the English historians brand

him as brigand, cutthroat, man of Belial, and so forth—and ascribe to him

inhuman atrocities. This indeed is by no means unnatural for writers of the

cloister, starting from Wallace's outlawry and his guerrilla warfare, and

cherishing a full share of the virulent international enmity. But while no

doubt very rough deeds were done in those days on both sides, 'Herodian

cruelties' are but the stock allegations of dislike at this period; and they

are hurled from both sides indiscriminately. Major expressly admits that

'towards all unwarlike persons, such as women and children, towards all who

claimed his mercy, he showed himself humane,' though 'the proud and all who

offered resistance he knew well how to curb.' The strong impression remains

that Wallace never, at any rate never without some overpowering constraint,

either did or permitted mere cruelty to any person. Hemingburgh's account of

the episode at Hexham speaks volumes in his favour.

The regrettable inadequacy of historical criticism of

Harry's poem prevents us, in the meantime, from illustrating the minor

military qualities of Wallace. But, admitted that he was 'a man of vast

military genius,' there is little necessity for detailed remarks on his care

and consideration for his men; on his men's confidence in him and affection

for him; on his sleepless vigilance, his high courage, his cool daring, his

masterful rule, his resolute tenacity and endurance, his keen sense of

honour, his singular unselfishness, his lofty magnanimity. Undoubtedly he

did not lack that 'bit of the devil in him,' without which, according to Sir

Charles Napier, 'no man can command.' Nothing in all Harry's panorama is

more nobly touching, or more illuminative, than the fidelity of the men that

stood closest to Wallace. Is it not true, though Harry says it, that, when

Steven of Ireland and Kerly rejoined their lost leader in the Tor Wood after

the annihilation of Elcho Park, 'for perfect joy they wept with all their

ecn'? Is not the lament of Wallace over the dead body of Sir John the Graham

on the field of Falkirk the true, as well as the supreme, expression of the

profound affection and confidence that united the goodly fellowship of these

tried comrades and dauntless men?

Burton, as we have seen, also acknowledges freely that

Wallace was 'a man of vast political genius.' The particulars are most

limited, and yet they are ample to ground a large inference. It will be

sufficient to recall his endeavours, in the midst of warlike activity, to

resuscitate industry and commerce, to reorganise the civil order, to secure

the aid of France and Rome, to minimise the friction with the barons, and to

observe and to enforce deference to constitutional principle. It is a

striking testimony to his greatness of mind that he was absolutely destitute

of ambition, as ambition is ordinarily understood. Emphatically he was a man

that 'cared not to be great, But as he saved or served the State.'

Even at the height of his power and popularity, he

does not seem to have had the faintest impulse to seize the crown, or indeed

to seize anything, for himself. Harry tells an extraordinary story, with a

definiteness that commands attention, how he took the crown for one day, on

Northallerton Moor, expressly and solely and most reluctantly 'to get

battle.' Whether he could have taken the crown and held it—if he had so

wished—need not tempt speculation. It is a singularly bright leaf in

Wallace's laurels that there remains no shadow of evidence of any

inclination on his part to swerve from the straight course of pure and

unselfish patriotism.

'Wallace,' says Major, 'whom the common people, with some of the nobles,

followed gladly, had a lofty spirit; and born, as he was, of no illustrious

house, he yet proved himself a better ruler in the simple armour of his

integrity than any of those nobles would have been.' And again: 'Wise and

prudent he was, and marked throughout his life by a loftiness of aim which

gives him a place, in my opinion, second to none in his day and generation.'

But beyond and above the exceptional tribute of 'vast

political and military genius '—a tribute doubly ample for any one man in

any century of a nation's history—it is the unique glory of Wallace that he

was the one man of his time that dared to champion the independence of his

country. More than that, though he died a cruel and shameful death amidst

the exultant insults of his country's foes in the capital city of the enemy,

he yet died victorious. He had kept alight the torch of Scottish freedom.

He, a man of the people, had taught the recreant nobles that resistance to

the invader was not hopeless, although those that took the torch immediately

from his hand failed to carry it on; and the light was preserved by the

commonalty till the torch was at length grasped by Bruce. Wallace, in fact,

had made the ascendency of Bruce possible--a possibility converted into a

certainty by the death of Edward I. Lord Rosebery has justly pointed to the

attitude of Edward towards him in 1304, as 'the greatest proof of Wallace's

eminence and power.' The true Deliverer of Scotland was Sir William Wallace.

The prime consideration is very finely singled out and

expressed by Lord Rosebery, in the address he delivered at the Stirling

Celebration in 1897—

'There

are junctures in the affairs of men when what is wanted is a Man—not

treasures, not fleets, not legions, but a Man—the man of the moment, the man

of the occasion, the man of Destiny, whose spirit attracts and unites and

inspires, whose capacity is congenial to the crisis, whose powers are equal

to the convulsion—the child and the outcome of the storm. . . . We recognise

in Wallace one of these men—a man of Fate given to Scotland in the storms of

the thirteenth century. It is that fact, the fact of his destiny and his

fatefulness, that succeeding generations have instinctively recognised.'

The instinct of the Scottish nation is thoroughly

sound. Though at one time nourished by Harry's poem, it is rooted in the

rock of historical fact. And, despite the sneers of the inconsiderate, it is

a great imperial influence. Who will assert that the empire has suffered

from the intense passion of freedom that Scotsmen associate with the name of

Wallace? Is it not the obvious fact that the free national feeling by

transmutation swells the imperial flame? If it is fundamentally due to

Wallace's heroic heart and mind that the national spirit of freedom saved

Scotland from union with England, on any terms less dignified than the

footing of independence, then the results of his noble struggle entitle him

to a foremost place among the great men that have established the

foundations of the British Empire. One sovereign at least of England as well

as of Scotland acknowledged - and handsomely acknowledged -'the good and

honourable service done of old by William Wallace for the defence of that

our kingdom.' Wallace made Scotland great; and, as Lord Rosebery proudly and

justly claimed, 'if Scotland were not great, the Empire of all the Britains

would not stand where it does.' In the work of imperial expansion,

consolidation, and administration, Scotsmen have done, and are doing, at

least their fair share; but that share would have been indefinitely

deferred, and indefinitely marred, but for the uncurbed passion of freedom

pervading their nature. And to Scotsmen, in all the generations, Freedom

will ever be nobly typified in the immortal name of SIR WILLIAM WALLACE.

|