|

LEAVING Dundaff, Wallace proceeded, in April 1297, to

Lanark, attended by nine men. He joined his wife in a house just outside the

gate, and here Sir John the Graham came to him, with fifteen followers. Sir

William de Hazeirig, [Bower calls him William de Heslope (Hislop). The

indictment of Wallace has William de Hesebregg (Hazelrig); the b apparently

a clerical blunder for l. Mr. Joseph Bain (Cal. ii. p. xxvii.)

suggests Andrew de Livingstone, not convincingly. Livingstone preceded

Hazelrig.] the Sheriff, the oppressor of his wife's family, and Sir Robert

Thorn, presumably the Captain, soon devised a plan for taking him at

disadvantage. As Wallace was returning from mass one May morning with his

companions, not in armour, but pranked out in the civilian 'goodly green' of

the season, he was ostentatiously insulted by an English soldier—'the

starkest man that Hazelrig then knew.' He tried to get away without a

disturbance; but the arrival of Thorn and Hazeirig with some 200 men in

harness at once precipitated a conflict. The odds were overwhelming, and the

Scots retired through the gate, Wallace and Sir John doughtily defending the

rear. Reaching Wallace's house, they were let in by his wife, and passed out

by a back door, while she held the enemy in parley. They at once sought the

shelter of Cartland Crags.

According to Harry, the English, enraged at being baffled, put Wallace's

wife to death; but Harry professes himself unable to state the

circumstances. Wyntoun, whose account is extremely similar to Harry's, says

the Sheriff came to Lanark after the disturbance, and then caused her to be

put to death. He adds that Wallace secretly, but helplessly, beheld her

execution; an absolutely incredible assertion. Harry's version is certainly

nearer the facts. The English had killed Wallace's father; they had

persecuted his mother; now they had inhumanly murdered his wife. The cup was

running over.

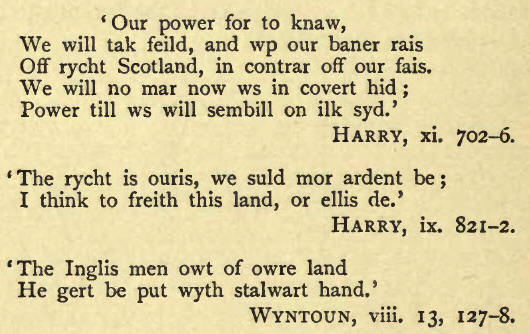

The distress of

Wallace and his friends is finely depicted by Harry. It inflamed them to a

desperate and exemplary revenge. Reinforced by Auchinleck with ten men,

Wallace and his party entered Lanark at night by different gates in twos and

threes, without exciting remark. Wallace made for Hazeirig; Sir John, for

Thorn. Dashing in the door with his foot, Wallace found Hazeirig in his

bedroom, and slew him on the spot, while Auchinleck, gave himself the

satisfaction of 'making sikkar' with three thrusts of his knife. Young

Hazelrig, rushing to the aid of his father, was also instantly slain.

Meantime Sir John had burnt Thorn in his house.

Wallace drew off to Clydesdale for aid. His terrible

wrongs and his signal revenge brought him troops of friends, and the hopes

of patriotic Scotsmen rose high. Sir John the Graham and Auchinleck were at

his side. Adam of Riccarton, Sir John of Tynto, Robert Boyd, and Crawford

(not Sir Reginald, who was in England), hastened to him. From Kyle and

Cunningham came 1000 horse. Presently Wallace found himself at the head of

3000 'likely men of war,' besides many footmen, who 'wanted horse and gear.'

One notable recruit deserves especial mention—Gilbert

de Grimsby, whom Wallace's men rechristened Jop. J op was a man 'of great

stature,' and already 'some part grey.' He was a Riccarton man by birth, and

had travelled far in Edward's service as 'a pursuivant in war,' though,

Harry says, he consistently refused to bear arms. No doubt he was the

'Gilbert de Grimmesby' that carried the sacred banner of St. John of

Beverley in Edward's progress through Scotland after Dunbar, a distinguished

service for which Edward on October 13, 1296, directed Warenne to find him a

living worth about 20 marks or pounds a year.

The news of the Lanark affray having reached Edward,

Harry marches up to Biggar an 'awful host' of 60,000 men under the 'awful

king' Edward, and scatters it like chaff before Wallace, killing thousands,

a fabulous number of the slain being near kinsmen of the King. But Edward

was certainly in England at the time, busily struggling with adversity in

his preparations 'to cross seas' to Flanders. He had, indeed, one eye on the

Scots. In the beginning of May he was having his 'engines' overhauled at

Carlisle; on May 24 he addressed a circular order to his leading liegemen in

Scotland to hear personally from certain high officers of 'certain matters

he had much at heart' in view of his intended departure to Flanders; and

through May and June he received the oaths of several Scots barons to serve

him 'in Scotland against the King of France.' But, so far as authentic

documents show, those preparations led elsewhere, not to Biggar. As there

exists no historical record of this Biggar expedition, and the local

tradition is most likely a mere echo of Harry's trumpet, the Marquess of

Bute and Dr. Moir may be right in the suggestion that Harry's battle of

Biggar is a duplicate of the later battle of Roslin. In any case, it must be

seriously modified both in dimensions and in details.

Harry's account of Wallace's subsequent doings in the

south-west must at present be left in a tangle of misconceptions. The

dreadful story of the Barns of Ayr, however, claims notice. The details of

the treacherous preparations must be rejected, or at least held in grave

suspense. The alleged result was that some 360 of the leading Scots of the

district-Sir Reginald Crawford, Sir Brice Blair, Sir Niel Montgomery,

Crawfords, Kennedys, Campbells, Barclays, Boyds, Stewarts, and so

forth—being summoned to attend an eyre at Ayr on June 18, were hanged as

they entered, one by one, in the 'Barns,' or barracks, where the meeting was

convened. Wallace, who had been specially aimed at, escaped by an accident.

Gathering what men he could muster on the spur of the moment—some 300—he

came to the Barns at night, fired them, and burnt and slew all the English

there. Next he took the castle, but there were only a handful of men in it.

Supplementary to the revenge taken by Wallace was 'the Friars' Blessing of

Ayr'; for Friar Drumlay, the Prior, who had 140 English quartered with him,

simultaneously rose with seven of his brethren, donned harness, and took

arms, and slew most of his guests, the few that escaped being drowned. Harry

reckons the whole slaughter bill at 5000.

What may be the kernel, or fragments, of truth in the

story cannot now be stated. Certainly Sir Reginald Crawford was alive after

June 18. Arnuif the Justice may, as the Marquess of Bute suggests, stand for

Ormsby the Justiciar, who was attacked by Wallace at Scone. The Marquess

looks for explanation to the occasion of Edward's visit to Ayr on August 26,

1298, when the English found Ayr Castle burnt and abandoned. Lord Hailes

supposes the story may have taken origin in the pillaging of the English

quarters at Irvine in July 1297. Possibly there is a jumble and an

exaggeration and distortion of all these facts. But there must be something

deeper. The event is mentioned as well known, not only by Harry, but also by

Barbour and Major, and in the Gomplayni of Scotland. The story, as it

stands, does not fit into the known history of the time and place alleged,

and must be reserved for more adequate examination.

Wallace, according to Harry, proceeded straight to

Glasgow, fearing that Bek and Percy might be perpetrating a similar atrocity

at the eyre of justice they were holding for Clydesdale. He defeated the

English in a stiff combat, killing Percy quite unhistorically. Bishop Bek,

with an escort, escaped to Bothwell, whither Wallace pursued him, but

apparently he could not take him out of the hands of Sir Aymer de Valence.

Bek was no doubt in Scotland somewhere about this time—perhaps two or three

months later than Harry supposes; for Edward had sent him to report

personally on the state of affairs, concerning which various unwelcome

indications had reached him.

One especially unwelcome report, which the chroniclers specify as the

immediate reason for despatching Bek, informed the King of a daring attack

upon Ormsby, his Justiciar, at Scone, by Wallace and Douglas. Ormsby

demanded homage and fealty, and visited non-performance with the utmost

severity. 'The temper of Scotland at that season,' says Lord Hailes,

'required vigilance, courage, liberality, and moderation in its rulers. The

ministers of Edward displayed none of these qualities. While other objects

of interest or ambition occupied his thoughts, the administration of his

officers became more and more abhorred and feeble.' This is true of Ormsby,

and true generally. Ormsby, forewarned of the approach of Wallace, just

managed to escape, leaving all his goods and chattels to the spoilers.

Wallace and Douglas, it is said, killed a great many Englishmen, and laid

siege to several castles; but the details are not available.

The date of the attack on Ormsby is given by the

chroniclers as May; but the seriousness of the situation must have impressed

Edward before then, for we have seen that by this time he was preparing for

a 'Scottish war.' The insurrectionary feeling was certainly stirring all

over the country, and not merely within the range of Wallace's known

operations. About this time, or a little later, Macduff had made an

ineffectual rising in Fife; on August 1, Warenne reports from Berwick that

the Earl of Strathearn had captured Macduff and his two sons, and 'they

shall receive their deserts when they arrive.' About this time, or very

little later, Sir Alexander of Argyll was reported to have taken the

Steward's castle of Glasrog, and to have invaded Alexander of the Isles, a

liegeman of Edward. Has this anything to do with the expedition that Harry

sends Wallace on to Argyll for the rescue of Campbell of Lochawe from

MacFadyen, whom Edward had made Lord of Argyll and Lorn? After giving over

the pursuit of Bek, Wallace had retired to Dundaff, where Duncan of Lorn

found him and besought his aid. Wallace promptly responded to the call of

his old schoolfellow, defeated MacFadyen, and established Campbell and

Duncan in their lands. At Ardchattan many men rallied to his standard,

including Sir John Ramsay of Auchterhouse, who had long held out in

Strathearn; and with them he proceeded to attack St. Johnston. Whatever the

blunders in Harry's details, it is quite certain that there now was revolt

against English supremacy in Argyll.

The chroniclers join Douglas with Wallace in the

attack on Ormsby. Harry does not mention the episode at all; and if he

confuses it with the Barns of Ayr, he does not mention Douglas as present.

It may be supposed that Douglas had come south from Scone, and was engaged

on a separate enterprise. Harry first puts him in independent action at a

much later—and impossible—period. He makes Douglas attack and capture

Sanquhar Castle; whereupon the captain of Durisdeer raised the Enoch,

Tibbermoor, and Lochmaben, and besieged him in Sanquhar. Douglas, in

distress, sent for aid to Wallace, then in the Lennox. May it be Argyll, and

not the Lennox? Or did Wallace go to the Lennox after driving Bek out of

Glasgow? The event must have been about this time, if ever. At any rate,

Wallace promptly relieved him; defeated the English at Dalswinton, slaying

500; and made Douglas keeper from Drumlanrig to Ayr. Be all this as it may,

Edward on June 12 confiscated all Douglas's lands and goods in Essex and

Northumberland; which seems to indicate that by that date he had learned

that Douglas had forsworn his liege lord.

In Galloway, Edward had further trouble with the

shifty Bruce of Carrick. When the disturbance took place at Scone, the

Bishop of Carlisle, acting with Edward's other high officers in these parts,

summoned Bruce to appear, and exacted from him an oath that he would lend

faithful aid to the King against the Scots. This may have had nothing

whatever to do with the Scone attack, but may have been simply a part in the

regular preparations that were going on for the 'Scottish war.' Bruce is

supposed to have made a display of his fidelity by the raid he presently

made upon the lands of Douglas, which he harried with fire and sword,

carrying off Douglas's wife and children to Annandale. It is, however, an

obvious suggestion that this vicious foray was a counterblow for the burning

of Turnberry Castle in the Biggar campaign, if Douglas was with Wallace in

that enterprise, as, on Harry's story, he probably was. Such an

interpretation of Bruce's action would tend to confirm Harry on the point;

and there was no clear need for Bruce to signalise his fidelity in that

particular fashion.

At the

same time, Bruce may have done it in order to cloak the conspiracy he was

hatching in concert with the Bishop of Glasgow, the Steward, and the

Steward's brother John. When the scheme was ripe, Bruce attempted in vain to

raise his father's men of Annandale, but he was supported by his own men of

Carrick. His party at once fell on burning and slaying, and the chroniclers

specially mention the expulsion and contumelious treatment of the English

ecclesiastics. If such expulsion was in furtherance of the execution of the

edict of April 1296, hitherto held in abeyance by the English domination,

that was but a very subordinate consideration. The popular view seems to

have been that Bruce was aspiring to the throne. Probably enough, at any

rate, he thought that he might lead the nobles to the success that was

likely otherwise to crown Wallace. There is no trace of any direct personal

connection of Wallace with this movement—no trace except a blunder of

Rishanger's, who mentions both Wallace and Andrew de Moray, (?Thomas or

Herbert de Morham), but Walter of Hemingburgh rightly gives Douglas in place

of Wallace, and omits Moray. Bruce, of course, could not have been expected

to put himself under the leadership of a mere landless squire, whose proper

place he would have considered to be that of a henchman of his own—a squire,

moreover, that consistently professed to act as the liegeman of King John.

No; the rising most probably represents an independent attempt of Bruce's

party, on the suggestion of Wallace's successes.

Burton is not unnaturally surprised to find Sir

William Douglas in Bruce's party. It would be easier for the Douglas pride

to bow to Bruce than to Wallace; and the raid on the Douglas estates might

be held to cancel the burning of Turnberry, or might otherwise receive a

large atonement. In any case, there is barely room for doubt that Douglas

eventually, if not from the first, cast in his lot with Bruce. The plot

proved a complete fiasco. An English army was upon them. In the first days

of June, Edward had appointed Percy and Clifford 'to arrest, imprison, and

"justify" all disturbers of the peace in Scotland and their resetters.'

Having at length, with great difficulty, raised an army of 300 mounted

men-at- arms and 40,000 foot in England north of Trent, Percy and Clifford

entered Annandale early in July. Pushing on to Ayr, they learned that the

Scots force was near Irvine. The Scots barons are represented at sixes and

sevens; so selfishly at strife, that Sir Richard de Lundy, who had never

done homage to Edward, passed over to Percy in open disgust at their

discord. At any rate, they had neither men nor military capacity nor

patriotic ardour to stand up against the English army. They at once sued for

terms. On July 7, at Irvine, Percy and Clifford received them to Edward's

peace, provisionally promising them their lives, property, and personal

liberty, but requiring hostages. Such a pusillanimous collapse of the joint

enterprise of half a dozen of the most powerful Scots nobles, the natural

leaders of the nation, with young Bruce himself at their head, may suggest

some measure of the courage, resource, and patriotism of the youthful and

obscure Wallace—especially if we look but two months ahead to the signal

victory of Stirling.

The

craven spirit of these barons is pilloried in the ignominious document

recording their appeal to Warenne to support the convention with Percy.

There they stated shamelessly that they had been afraid lest Edward's coming

army should harry their lands, and that they had been surely informed that

the King would impress 'all the middle people of Scotland' for his war over

sea. They had accordingly taken up arms in defence, until they could protect

themselves by treaty from such a grievance and dishonour. 'And therefore,

when the English army entered within the land, they came to meet them, and

had such a conference that all of them came to the peace and the fealty of

our lord the King.' Yet their disgraceful treaty, negotiated by the Bishop

of Glasgow, acknowledges that they had committed 'acts of arson, slaughter,

and plunder.' They had to put the best face upon a weak case. There was

vastly more spirit in the nameless Scots and Glaswegians that plundered the

English baggage in Irvine, slaying over 500 of the enemy, while their

betters were grovelling to Percy and Clifford for admission to the peace of

the usurper.

On July 15,

Percy and Clifford reached Roxburgh, where they found Cressingham with 300

covered horses and Io,000 foot soldiers, ready to march to their aid next

morning. Cressingham's report to the King on July 23 throws interesting

side-lights on the situation. Percy and Clifford appear to have thought that

the whole object of the expedition had been accomplished. Cressingham,

however, urged that 'even though peace had been made on this side the Scots

water, yet it would be well to make a chevachie on the enemies on the other

side'; or, at any rate, 'that an attack should be made upon William Wallace,

who lay then with a large company—and does so still—in the Forest of

Selkirk, like one that holds himself against your peace.' We shall presently

see that the Scots north of Forth were tolerably active. Meantime

Cressingham's reference to Wallace, as well as the formal treaty, appears to

indicate all but conclusively that Wallace was no partner of the barons in

the fiasco of Irvine. In the result Percy and Cressingham concluded to make

no expedition until Warenne should arrive from England.

The next day both Cressingham and Spaldington wrote

further particulars to Edward. Spaldington informed him that 'because Sir

William Douglas has not kept the covenants he made with Sir Henry de

Percy'—that is, had failed to provide hostages or guarantors-'he is in your

castle of Berwick, in my keeping, and he is still very savage and very

abusive; but,' he added with dutiful zest, 'I will keep him in such wise

that, please God, he shall by no means get out.' Douglas was put in irons.

On October 12, he was consigned to the Tower of London, and on January 20,

1298-99, he is reported as 'with God.' Again, Cressingham's letter of July

24 shows the irksomeness of the English position. Edward, who had met almost

insuperable difficulties in fitting out his Flanders expedition, had urged

him to raise money from the issues and the rents of the realm of Scotland to

aid Warenne and Percy in their military operations. 'Not a penny could be

raised,' says Cressingham, 'until my lord the Earl of Warenne shall enter

into your land and compel the people by force and sentence of law.' More

than that

'Sire, let it not

displease you, by far the greater part of your counties of the realm of

Scotland are still unprovided with keepers, as well by death, sieges, or

imprisonment; and some have given up their bailiwicks, and others neither

will nor dare return; and in sonic counties the Scots have established and

placed bailiffs and ministers, so that no county is in proper order,

excepting Berwick and Roxburgh, and this only lately.'

After all, Harry may not be far wrong in stating that

Wallace appointed sheriffs and captains from 'Gamlispath' to Urr Water, and

controlled Galloway, after the alleged battle of Biggar. It may be also, as

he says, that Douglas came to Wallace's peace at that time, and ruled from

Drumlanrig to Ayr as his lieutenant. In any case, Cressingham's letter marks

emphatically the strength of the silent, as well as of the active,

resistance of the people of Scotland. The impecunious and helpless Treasurer

could qualify his rueful report by only one vague crumb of comfort. 'But,

sire, all this will be speedily amended, by the grace of God, by the arrival

of the said lord the Earl, Sir Henry de Percy, and Sir Robert Clifford, and

the others of your Council.'

The alleged delay of the barons in giving hostages is attributed by the more

trusted chroniclers to the urgency of Wallace. First Douglas, and then the

Bishop, surrendered their liberty, pricked (it is said) by insulting

suspicions of their honour. But this seems to be matter of inference, not of

fact. For on August i, Warenne wrote to Edward: 'Sir William de Douglas is

in your castle of Berwick, in good irons and in good keeping, for that he

failed to produce his hostages on the day appointed him, as the others did.'

As for the Bishop, Edward's own theory, based (he said) on intercepted

correspondence of Wishart, was, that he had voluntarily submitted to

internment in Roxburgh Castle, in order to plot for its betrayal to the

Scots. One would like to see that correspondence. No doubt the compulsion in

both cases was altogether external. At any rate, we are told that Wallace

was extremely angry when he heard of their surrender; and that, in his rage,

he harried the Bishop's house, carrying off his furniture, arms, and horses.

Possibly he did; possibly, too, the true story may be that this was the

harrying of Bishop Bek, not of Bishop Wishart, in Glasgow. It is further

admitted that his followers increased to an immense number, the community of

the land following him as their leader and chief, and the whole of the

retainers of the magnates adhering to him; 'and although the magnates

themselves were with our King in the body, yet their heart was far from

him.' This picture agrees fully with the lamentable report of Cressingham.

The trouble in the north was certainly not to be

ignored, as Cressingham well knew. Andrew de Moray, son of Sir Andrew de

Moray (since Dunbar a prisoner in the Tower), was at the head of an

insurrection of considerable magnitude. The Bishop of Aberdeen, and Gartnet,

the son of the Earl of Mar, had proceeded to quell it; and early in June

Edward had despatched to their aid the Earl of Buchan, and later the Earl of

Mar. Mar, Comyn, and Gartnet reported on July 25, that on July 17 at Launoy

(?) on the Spey 'met us Andrew de Moray with a great body of rogues,' and

'the aforesaid rogues betook themselves into a very great stronghold of bog

and wood, where no horseman could be of service.' They mention 'the great

damage which is in the country,' and send Sir Andrew de Rathe to inform him

particularly. It is instructive to observe that, when Sir Andrew showed his

credence to Cressingham at Berwick, Cressingham warned Edward (August ) to

give little weight to it, for it 'is false in many points, and obscure, as

will be well known hereafter, I fear.' On the same date the Constable of

Urquhart reported how Moray had besieged his castle; and about the same time

Sir Reginald Ic Cheyne informed Edward how Moray and his 'malefactors' had

spoiled and laid waste his goods and lands. Apparently a peace had been

patched up somehow; for on August 28 letters of safe-conduct were issued in

favour of Andrew de Moray, and of Hugh, son of the Earl of Ross, whose

Countess had brought material aid to the English party against Andrew de

Moray, to enable both men to visit their fathers in the Tower of London.

Andrew de Moray, however, could not have used his safe-conduct, for he

fought at Stirling Bridge. By this time Aberdeen was also in revolt. On

August 1, Warenne reports that 'we have sent to take Sir Henry de Lazom, who

is in your castle of Aberdeen, and there makes a great lord of himself.'

Warenne has not yet heard of Lazom's fate; but he can promise that 'if he be

caught he shall be honoured according to his deserts.'

Wallace, whatever his strength in Selkirk Forest,

evidently felt it inexpedient to offer direct opposition to the troops under

Percy and Cressingham at Roxburgh, and under Spaldington at Berwick. He went

north, no doubt by Glasgow, if it be true that it was now he harried the

facile bishop—or the astute one either. His force augmented steadily as he

marched onward. It may have been at this time that he made the expedition

into Argyll and Lorn; it may have been at the earlier date previously

mentioned. For some little space we must again fall back on the guidance of

Harry, who, as we have just seen, brings him from Ardchattan to the siege of

St. Johnston. The details that Harry supplies give an air of verisimilitude

to his narrative. He tells how Sir John Ramsay had 'bestials' of wood made

in the forest, and floated them down the river; how the troops filled the

dykes with earth and stone, and advanced the 'bestials' to the walls; and

how Wallace, Ramsay, and Graham at last sacked the town, slaying 2000.

Ruthven, who had joined with thirty men, and distinguished himself in the

siege, Wallace installed as Captain and Sheriff,with the hereditary

lieutenancy of Strathearn.

'Then to the north good Wallace made him boun.'

Having first made a flying visit to Cupar, whence the

English abbot had fled, Wallace swept over the north country with his

accustomed energy. At Glammis he was joined by Bishop Sinclair; Brechin was

reached the same night. Next morning Wallace displayed 'the banner of

Scotland,' and rode through the Mearns 'in plain battle' to Dunnottar

Castle, where some 4000 English had taken refuge. He destroyed them all,

even burning down the church, which was full of refugees; not even the

intercession of the bishop could save them, for Wallace had fresh on his

mind the atrocities of the Barns of Ayr.

Hastening to Aberdeen, Wallace suddenly fell upon the

shipping, and destroyed it. Harry mentions no difficulty with the garrison.

Wallace at once swept through Buchan, and then round the further north. It

is impossible to say how the tour was affected by the results of the recent

operations of Andrew de Moray west of the Spey. On August i—a rather early

date—Wallace was back in Aberdeen, making arrangements for the

administration of the north. He immediately passed south to the siege of

Dundee.

There are some historical blunders in Harry's sketch of Wallace's

northern expedition. Thus, Sinclair, though a good patriot, was not Bishop

of Dunkeld till 1308, at any rate, not 'with the Pope's consent'; Matthew de

Crambeth was bishop from 1288 to 1304 at least. Sir Henry de Beaumont, too,

whom Harry drives out of Buchan, was not earl till some ten years later.

Again, if Wallace was in Selkirk Forest on July 23, as Cressingham reported,

he could not, with all his celerity, have overrun the north and been back in

Aberdeen by August 1. It does not, however, by any means follow that Harry's

account is not fairly right in substance. In any case, it seems certain that

the whole of Scotland north of the Forth—except Dundee and Stirling—was

under the sway of Wallace just before the battle of Stirling Bridge.

On August 22, Edward embarked for Flanders, and did

not return to England till March 14. A few days before sailing (August 14),

he had designated Sir Brian Fitz Alan to succeed Warenne as Governor of

Scotland, Warenne being ill and anxious to be relieved. In obedience to

urgent orders to remain at his post, however, Warenne had gone north at the

head of the English army, and was making for Stirling. On hearing of his

approach, Wallace left one of his lieutenants to carry on the siege of

Dundee, and hastened to dispute the passage of the Forth. He could not

occupy Stirling Castle, for the castle was not, as Harry says, in the hands

of Earl Malcolm (who, on the contrary, was in the English camp), but had

been in the hands of Sir Richard de Waldegrave, the English Constable, since

September 8, 1296. Wallace chose his position with the instinct of military

genius. With his back to the Abbey Craig and the Ochils above the Abbey of

Cambuskenneth, and with a loop of the Forth protecting him in front, he

commanded at his will the head of the bridge that lay between him and the

enemy. He is said to have had 18o horse and 40,000 foot, while Warenne had

1000 horse and 50,000 foot; but little reliance can be placed on the

figures. Cressingham, it is said, had directed Percy to disband his army of

the west, believing that the force under Warenne was amply sufficient for

the campaign.

As the armies

lay in view of each other, with the river rolling between them, negotiations

took place with a view to some accommodation. The Steward of Scotland and

Earl Malcolm of the Lennox readily obtained Warenne's permission to try what

they could do in representations to Wallace. Wallace, however, was

absolutely irreconcilable. Warenne next despatched two friars to Wallace, to

invite him and his men to come to the King's peace, promising impunity for

all past offences. 'Take back for answer,' said Wallace, 'that we are not

here to sue for peace, but are ready to fight for the freedom of ourselves

and of our country. Let the English come on when they please, they shall

find us ready to meet them to their beards.' The reply might have been

anticipated.

In the English

camp the report of the friars was correctly interpreted as a plain defiance,

and strengthened the clamour of Cressingham and his friends for an immediate

attack on the presumptuous Scots. Warenne, ill, and anxious to reach an easy

settlement, was unable to withstand 'the ignorant impetuosity' of the

overbearing churchman. Sir Richard de Lundy, whom Harry mistakenly ranges on

the side of Wallace, interposed with a wise suggestion. He pointed out the

fatal folly of attempting to advance over the bridge, which allowed only two

to pass abreast; by that way 'we are dead men.' He offered to take a party

of 500 horse and a detachment of infantry across a ford—'probably the ford

of Maner,' Hailes thinks—and catch the enemy in the rear. Lundy's proposal

was declined, on the flimsy ground that it would divide the army, the real

ground probably being doubt of his fidelity. Still Warenne hesitated. 'Why

do we drag out the war in this fashion,' urged the Treasurer, 'and waste the

King's treasure? Let us fight, as is our bounden duty.' Warenne at last gave

way.

On the morning of

September 11, Cressingham led the English van across the narrow bridge of

Stirling. From the slopes of the Abbey Craig—over which now towers the

imposing National Monument—Wallace sternly watched them defiling in steady

movement all the morning till eleven o'clock. At the critical moment he sent

the blast of his horn thrilling through the valley, the signal to launch his

eager men upon the English van. While the main bodies of the combatants met

in deadly shock, a company of Scots seized and held the head of the bridge.

This movement was no sooner realised than it embarrassed and disordered the

advancing English, and struck apprehension into the hearts of such as had

passed over. Hopeless confusion passed into irretrievable disaster. The

English vanguard was cut to pieces or driven into the Forth. Cressingham

himself was slain. Sir Marmaduke Twenge, who had been among the first to

cross, seeing the inevitable rout, cut his way back to the bridge with

conspicuous valour, and effected his escape. This remarkable exception

indicates forcibly the plight of the rest. As the English drew back from the

bridge, the Scots pressed vehemently upon them. Warenne, who had not crossed

the river, promptly took to horse, and, ill as he was, did not draw bridle

till he reached Berwick, and did not rest till he was safe on the English

side of the Border.

It is

said that the Scots flayed Cressingham's body and distributed the skin in

strips. So deeply was he detested in life, that it is far from unlikely that

his enemies took a morbid revenge upon him in death. After all, it is only

sentimentally worse than the fate he narrowly escaped at the hands of his

own men, who were incensed almost to the point of stoning him to death for

declining the aid of Percy's force. Still the fact, if a fact, is to be

regretted; although the Furies were let loose.

The Steward and Earl Malcolm are represented as

playing a double part, at which the Steward, at any rate, was getting well

practised. Having failed to arrange an accommodation with Wallace, they had

promised Warenne to bring him some forty more horse on the day of battle.

They discreetly waited to see how the event would declare itself, and then

calmly stood on the winning side with contemptible judiciousness.

The Scots at once entered upon an eager pursuit of

Warenne's flying army. Harry traces the English flight through the Tor Wood,

and on to Haddington and Dunbar, marking the route by large chronicles of

the slain. Wallace at once returned to Stirling. The Constable of the

castle, Sir Richard de Waldegrave, and great part of the garrison, had been

killed at the bridge; and Warenne had given the command to Sir William de

Fitz Warin, with whom was the redoubtable Sir Marmaduke de Twenge, and

'other good soldiers.' The castle was quickly reduced 'from want of

victuals.' Sir William de Ros, by his own account, was one of the captives,

and 'William le Waleys spared his life from being Sir Robert's brother (?

cousin); but as he would not renounce his allegiance, sent him a prisoner to

Dumbarton Castle, where he lay in irons and hunger till its surrender to the

King after the battle of Falkirk.' On April 7, 1299, Edward authorised

negotiations for the exchange of a number of prisoners, including Fitz Warm,

Twenge, and Ros. Fitz Warin died the same year (before Dec. 23). The fate of

the rest of the garrison was probably similar.

Harry tells how Wallace received all the barons that

were willing to come to him, requiring them all to swear 'a great oath' to

be loyal to himself and to Scotland, with the alternative of death or

imprisonment. Sir John de Menteith he mentions specifically as having taken

the oath. But this subordination of the 'barons'—in spirit at least—is to be

accepted with some reserve; though an English annalist also tells us that

the Scots adhered to Wallace, 'from the least to the greatest'; and the

papers about 'ordinances and confederations,' found on Wallace's person when

he was captured, point to a concordat of some sort. Dundee was at once

evacuated; and in ten days not an English captain was left in Scotland,

except in Berwick and Roxburgh. Wallace had at length achieved the

deliverance of Scotland.

|