|

“Let there be truth

between us”

The number who attain

the years vouchsafed our venerated friend are few, but the number

who, like him, have filled the measure of their days so acceptably

to their fellow men, not only of this age, but for all time to come,

are, and ever will be, far fewer.

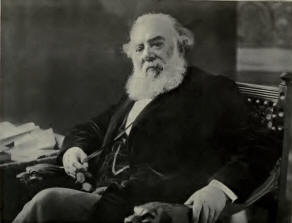

Alexander Melville Bell, born in Edinburg, Scotland, March ist,

1819, had three distinct periods of professional life. The first

twenty-four years, that of Student, the succeeding twenty-seven

years, that of Teacher, and the last thirty-five years, that of

Master. Owing to the fact at the time of birth, that his father,

Alexander Bell, then already recognized as a leading instructor of

elocution, had achieved notable success in the treatment of

defective speech, the son from earliest infancy entered at home an

environment of student life exceptionally calculated to fit him for

the career in which he so signally distinguished himself. The

father’s inherent love of truth and frankness begat in his son like

traits of character. This was so pronounced a feature that at the

early age of twenty-four years upon independently entering the

vocation of teacher, in contrast to certain widely heralded

instructors of the period like the Braidwoods and others, who sought

by every means either to throw an air of mystery, or exclusive

secrecy, around their methods, Mr. Bell commenced giving publicity

in print by “communicating unreservedly the principles” underlying

his methods. In evidence thus of his strong aversion to every form

of sham, then so largely prevailing in his profession, he lost no

opportunity to emphasize the position he had taken of strict

fairness towards his pupils and the public generally. We thus find

him in the earliest edition of his well-known and deservedly

standard Manual, “Faults of Speech/’ emphatically stating in regard

to stammering:

“The Stammerer’s difficulty is, where to turn for effective

assistance. Certainly not to any pretender who veils his method in

convenient secrecy, nor to any who profess to ‘charm’ away the

impediment, or to effect a cure in a single lesson! Not to any whose

‘system’ involves drawling, singing, sniffling, whistling, stamping,

beating time—all of which expedients have constituted the ‘curative’

means of various charlatans; nor to any who bridle the mouth with

mechaniccl appliances, forks on the tongue, tubes between the lips,

bands over the larynx, pebbles in the mouth, etc., etc. The habit of

stammering can only be counteracted by the cultivation of a habit of

correct speaking founded on the application of natural principles.

Respecting these the e is no mystery except what arises from the

little attention that has been paid to the Science of Speech”

The perfect candor with which he habitually addressed alike his

pupils and the public at large, nowhere appears more forcibly

presented than in the introductory essay to his standard work

entitled: “Principles of Elocution,” where, among other things, he

says:

“Elocution may be defined as the effective expression of thought an

I sentiment by speech, intonation and gesture, * * * *. Elocution

does not occupy the place it reasonably ought to fill in the

curriculum of education. The causes of thi§ neglect will be found to

consist mainly of these two; the subject is undervalued, because it

is misunderstood, and it is misunderstood, because it is unworthily

represented, in the great majority of books, which take its name on

their title page; and also by the practice of too many of its

teachers, who make an idle display in recitation, the chief, if not

the only end of their instruction. * * * * The study of oratory is

hindered by another prejudice, founded—too justly—on the ordinary

methods and results of elocutionary teaching; the methods being

unphilosophical and trivial, and their result not an improved

manner, but an induced mannerism. The principle of instruction to

which Elocution owes its meanness of reputation may be expressed in

one word,— Imitation.

“But adherents of the imitative methods urge, they teach by Rule.

There has been far too much teaching by ‘Rules,’ * * * * which are

but logical deductions from understood principles. * * * * The rules

of nature are few and simple, at the same time extensive and obvious

in their application. These are Principles rather than rules, and it

is the highest business of philosophy to find out^such,* * * *.

Elocutionary exercise is popularly supposed to consist of merely

Recitation, and the fallacy is kept up both in schools and colleges.

* * * * This is a miserable trifling with an art of importance, and

art that embraces the whole Science of Speech.”

The “teacher” period of Mr. Bell’s professional life, as stated by

himself in the address he delivered June 29th, 1899, before the

National Association of Elocutionists, “began in 1843, and finished

in 1870,” a period of strenuous activity and achievement, such as

rarely falls to the lot of man. Apart from his regular engagements

as instructor in the University of Edinburg, London, and other

lesser institutions, the number of private pupils and continuous

lectures and readings in public, would stagger any one to

successfully accomplish, unless possessed of Prof. Bell’s Scotch

constitutional vigor, moral firmness, and simple mode of life. The

fact is, were all that Alexander Melville Bell said and did written

and fully told, it would constitute a goodly portion of a

well-stocked private library. In 1842, already at the age of

twenty-three years, he announced the formulation of a new theory of

articulation and vocal expression. Although his father did not

endorse all of his conclusions, he accorded them general approval.

The event of the inception of this new theory, which permeated more

or less all of his succeeding professional labors later on, is thus

graphically described by his. life-long and devoted friend, the

genial and gifted Rev. David Macrea:

“I happened to be at his house on the memorable night when, busy in

his den, there flashed upon him the idea of a physiological alphabet

which would furnish to the eye a complete guide to the production of

any oral sound by showing in the very forms of the letter the

position and action of the organs of speech which its production

required. It was the end toward which years of thought and study had

been bringing him, but all the same, it came upon him like a sudden

revelation, as a landscape might flash upon the vision of a man

emerging from a forest. He took me into his den to tell me about it,

and all that evening I could detect signs in his eye and voice of

the exultation he was trying to suppress. At times it looked as if,

like Archimedes, he might give vent to his emotions and shout

‘Eureka.' '

After elaborating his system, he taught it to his younger sons,

Alexander Graham and Charles Edward. His friend then had him give a

public demonstration in the Glasgow Athenaeum, preceded by a private

exhibition at the residence of the Reverend gentleman’s father. Of

this exhibit, Mr. Macrea states:

“We had a few friends with us that afternoon, and when Bell’s sons

had been sent away to another part of the house out of earshot, we

gave Bell the most peculiar and difficult sounds we could think of,

including words from the French and Gaelic, following these with

inarticulate sounds, as of kissing, chuckling, etc. All these Bell

wrote down in his Visible Speech alphabet, and his sons were then

called in. I well remember our keen interest, and by and by,

astonishment, as the lads—not yet thoroughly versed in the new

alphabet—stood side by side looking earnestly at the paper their

father had put in their hands, and slowly reproducing sound after

sound just as we uttered them. Some of these sounds were quite

incapable of phonetic representation with our alphabet. One friend

in the company had given as his contribution, a long yawning sound,

uttered as he stretched his arms and slowly twisted his body, like

one in the last stage of weariness. Of course, visible speech could

only represent the sound, not the physical movement, and I well

remember the shouts of laughter that followed when the lads, after

studying earnestly the symbols before them, reproduced the sound

faithfully; but like the ghost of its former self in its detachment

from the stretching and body twisting with which it had originally

been combined.”

This discovery, that the mechanism of speech operating on the organs

of voice, acts in a uniform manner for the production of the same

Oral effect in different individuals or persons of differing

nationality, and his success in devising a scientifically correct,

and physiological analogous system of graphic presentation which he

termed “Visible Speech, the Science of Universal Alphabetics,”

indisputably ranks Professor A. M. Bell as foremost master of the

“Science of Speech.” No less an authority than Dr. Alexander John

Ellis, the greatest phonetician, and most scholarly writer on

phonetics of the last century, after having carefully studied and

considered the achievement of Prof. Bell, unequivocally corroborates

this by stating in concluding an elaborate description of the Bell

system:

“As I write, I have full and distinct recollection of the labors of

Amman, DuKempelen, Johannes Muller, K. M'. Rapp, C. R. Lepsius E.

Brucke, S. S. Haldeman, and Max Muller. To those I may add my own

works of more or less pretension and value * * * *. I feel called

upon to declare that until Mr. Melville Bell unfolded to me his

careful, elaborate, yet simple and complete system, I had no

knowledge of alphabetics as a science, * * * *. Alphabetics as a

science, so far as I have been able to ascertain,—and I have lo'oked

for it far ?nd wide,—did not exist, * * * * I am afraid my language

may seem exaggerated, and yet I have endeavored to moderate my tone,

and have purposely abstained from giving full expression to the high

satisfaction I have derived from my insight into the theory and

practice of^Mr. Melville Bell’s “Visible Speech,” as it is rightly

named.”1

^‘The Reader,” London, September 3rd, 1864.

In the generosity of his nature, Mr. Bell, without recompense,

ineffectually offered to the British Government, pro bono publico,

“all. copyright in the system and its applications, in order that

the use of the Universal Alphabet might be as free as that of common

letters to all persons.” Neither was his “request for an authorized

investigation” given attention; eliciting from him in the preface

of, his Inaugural Edition, “Visible Speech, the Science of Universal

Alphabetics,” issued 1867, that if “the subject did not lie within

the province of .any existing department * * * * does not the fact

that an offer of such a nature failed to obtain a hearing, indicate

a national want, the want namely of some functionary whose business

it should be to investigate new measures of any kind which may be

presented for the benefit of society.”

Meanwhile, in addition to his absorbing numerous engagements, he

labored indefatigably with his pen, issuing during his career as a

teacher in England, no less than seventeen works relating to speech,

vocal physiology, stenography, etc., including the existing standard

Manuals: “Principles of Elocution,” “Principles of Speech and

Dictionary of Sounds,” and jointly with his brother, David Charles

Bell, the “Standard Elocutionist,” of which upwards of two hundred

editions have appeared, and the demand for which continues unabated.

He commenced his career as teacher in Edinburg by giving instruction

to classes in connection with the university, and also with the New

College, up to the time of the death of his father, (1865), who had

followed his profession in London, whilst his eldest son, David

Charles, was tutor at the university in Dublin; the father and his

two sons thus being the leading elocutionists of the Capitals

of-England, Ireland, and Scotland. Prof. A. Melville Bell then

removed to London, leaving his eldest son, Melville James Bell, to

succeed him in Edinburg. In London, he received the appointment of

lecturer on Elocution in University College. There he remained until

1870, when, having already lost both his eldest and youngest sons,

he determined, on account of the threatening condition of the health

of his only remaining son, Alexander Graham, a third time, and on

this occasion permanently, to cross the Atlantic. He located at

“Tutelo Heights,” near Brantford, Ontario, where, for a number of

years he held the professorship of elocution in Queen’s College,

Kingston, and in addition delivered courses of lectures in Boston,

Mass., and in Montreal, Toronto, London, and other Canadian cities,

besides, jointly with his brother, Prof. David C. Bell, giving

numerous public readings.

Mr. Bell’s career as “Master” of the Science of Speech took

indisputable form soon after his father’s death. In 1868 already he

was called from London to give a course of lectures before the

Lowell Institute, Boston, Mass. Two years later, 1870, on his

permanent settlement in Canada, he was a second time invited to give

a course of twelve lectures before the Lowell Institute, which he

had the honor to supplement the following year, 1871, by a third

similar course. His residence at Brantford proved beneficial both to

himself, and to his son, Alexander Graham, who was engrossed there

in solving the problem of the telephone, and, upon fully recovering

his health, accepted a position in the Faculty of the Boston

University School of Oratory, and in 1872, opened in Boston an

“Establishment for the study of Vocal Physiology,” on the Board of

Instruction of which, later on, Prof. A. Melville Bell’s name

appears first. During this latter period, Mr. Bell’s earlier

publications in England were re-issued and supplemented, notably so

by a treatise on “Teaching Reading in Public Schools,” and “The

Faults of Speech,” which latter has attained its fifth edition, and

constitutes the only generally recognized Standard Manual upon the

subject of correcting defects of speech.

Dr. Alexander Graham Bell had meanwhile married, perfected and

patented the telephone, and permanently located in Washington City.

The father and the latter’s brother, however, being loath to leave

their enjoyable home in Ontario, only decided finally to do so early

in the year 1881, which gave occasion to a farewell banquet being

tendered Prof. A. M. Bell by the city authorities of Brantford and

his numerous friends, who desired to convey to him their sincere

regret that circumstances rendered it desirable he should leave

Brantford where he had resided during the past eleven years, loved

and respected by an ever widening circle of friends. The occasion

was heightened by the presence of Prof. D. C. Bell and Dr. Alexander

Graham Bell. In response to the toast, “The guest of the evening,”

and the unstinted encomiums paid both to him and to his brother by

the Mayor and other prominent citizens, Prof. Bell responded giving

in part the following interesting account of his coming to, and

sojourn in, Canada, and touchingly referred to the cause of his

departure:

“When I was a very young man, and somewhat delicate after a severe

illness, I crossed the Atlantic to take up my abode for a time with

a friend of my family in the island of Newfoundland. I was there

long enough to see a succession of all its seasons, and I found the

bracing climate so beneficial, that my visit undoubtedly laid the

foundation of a robust manhood. People talk of the fogs of

Newfoundland, but these hung over the banks, and not—or but

little—over the land. I have seen more fog in any one year in

London, than I did during all the thirty months I spent in the land

of ‘Cod.’ It was there that I commenced the exercise of my

profession, and it is curious now to think that my desire to visit

the United States before returning home was defeated by the

impossibility of getting directly from one country to the other. It

was then necessary to go to England on the way to America. History

we are told repeats itself. I am reminded of the saying by the

circumstance, that when I left Newfoundland, 1842, I had the honor

of being the recipient of a similar public leave-taking to that

which you are favoring me with tonight. In 1867 and 1870, I suffered

the grievous loss of two fine young men, first my youngest, and next

my eldest son,1 and the recollection of my early experience,

determined me to try the effect of change of climate for the benefit

of my only remaining son. I had received an invitation to deliver a

course of lectures in the Lowell Institute, Boston, in the Autumn of

1870, and in July of that year, I broke up my London home and

brought my family to Canada. Our plan was to give the climate a a

two years’ trial. This was eleven years ago, and my slim and

delicate looking son of those days developed into the sturdy

specimen of humanity with which you are all familiar. The facts are

worth recording, because they show the invigorating influence of the

Canadian climate, and may help other families in similar

circumstances to profit by our experience.

“I was happily led to Brantford by the accidental proximity of an

old friend, and I have seen no place within the bounds of Ontario

that I would prefer for a pleasant, quiet and healthful residence *

* * *. How is it then that, notwithstanding this declaration, I am

about to bid adieu to the land that I love so well? You all know my

son; the world knows his name, but only his friends know his heart

is as good as his name is great. I can safely say that no other

consideration that could be named, than to enjoy the society of our

only son would have induced us to forsake our lovely ‘Tutelo

Heights/ and our kind good friends of Brantford. He could not come

to us, so we resolved to go to him. * * * I now confidently feel

that my sojourn in Brantford will outlive my existence, because

under yon roof of mine the telephone was born. A ray of fame,

reflected from the son, will linger on the parental abode, * * * *.

Dr. Alexander Graham Bell being called upon to respond to the toast,

“The Telephone and the Photophone/' is reported to have said in the

course of his remarks relative to the removal of his father, that

the ties of flesh and blood were stronger than any other, and

therefore, he should be pardoned for causing the removal of his

parents from Canada. He spoke of the many works and inventions of

Prof. Melville Bell in Stenography, Visible Speech, Elocution, etc.

His stating that the “Telephone is due in a great measure to him,”

is reported to have been a generous admission that somewhat

surprised those who heard it. It is furthermore reported that he

gave some reminiscences of the early efforts that resulted in the

discovery of the telephone, and added that many steps in its

utilization were perfected at “Tutelo Heights.”

Prof. A. M. Bell and his brother, with their families, upon arrival

in Washington, soon located in two adjoining spacious old

residences, Nos. 1517 and 1525 Thirty-fifth Street, N. W. There,

with the exception of a brief, period before his demise, when he

removed to his son’s residence, 1331 Connecticut Ave., Prof. Bell

lived dispensing his wonted hospitality, and, amidst his books,

enjoying the intellectual atmosphere that pervaded his literary

“den.”

But these Masters of Elocution by no means remained idle spectators:

the elder brother being called upon repeatedly for his inimitable

renditions of noted authors, to which he added in 1895, “The

Reader’s Shakespeare, in three volumes, for the use of schools and

colleges, private and family reading, and for public and platform

delivery,” whilst his junior brother, designated the “Nestor of

Elocutionary Science,” constantly was called upon either by letter

or personally on the^part of the more eminent elocutionists,

philologists, and pedagogues of the age, to advise on matters

relating to the one science of which he was the undisputed head and

master. Not only this, during his twenty-five years of residence at

the Nation's Capital, of which, in the year 1898, he became a duly

incorporated citizen, he personally, upon invitation, delivered

lectures before the “American Association for the Advancement of

Science,” “Johns Hopkins University,” “Columbia University,” “Modern

Language Association,” “National Association of Elocutionists,” “New

York Teachers of Oratory,” and the “American Association to Promote

the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf,” etc., etc.

During the same period he issued a revised version of the

“Inaugural-edition of Visible Speech”; “Sounds and their Relations.”

now a standard Manual in Normal Training Schools for teachers of the

Deaf; also other Manuals on “Speech Reading and Articulation

Teaching,” “English Visible Speech in Twelve Lessons,” “Popular

Manual of Visible Speech and Vocal Physiology,” “World English the

Universal Language,’’ and “Handbook of World English,” “English Line

Writing on the basis of Visible Speech,” and, finally, “Science of

Speech,” together with a fifth edition of “Principles of Elocution.”

The time had arrived, when, despite pleadings of numerous

applicants, the venerated master must resolutely decline to give

verbal instruction, much as he mentally enjoyed teaching. One of the

last privileged personal pupils, now teaching in a prominent

institution for the deaf, thus speaks of her master’s method:

“Prof. Bell was a wonderful teacher, I never had his equal. His

explanations were so clear and full that at the end of a lesson it

was quite impossible to think of asking any further question. Every

possible uncertainty had been anticipated.”

The autographic testimonial of ability this pupil received was

equally unequivocal:

“Miss - was a pupil of mine in ‘Visible Speech,’ and distinguished

herself by aptitute in the study, and by rapid and solid progress in

the practice. Miss -— has fine abilities, and she will, I have no

doubt, do honor to any position, the duties of which she may

undertake.

“1525 35th Street, N. W.,

“Washington, D. C., July 16th, 1896.

“(Signed,)

The following tribute was paid the deceased in the Boston “School

Document No. 9, 1905”:

“We can perhaps make no greater acknowledgment of indebtedness to

the late Prof. Alexander Melville Bell, the distinguished

philologist, who, in 1870, upon invitation, told the teachers how

his system of phonetic writing, named by him Visible Speech, could

be made useful in the development of the speech of deaf children,

than to say that it continues to be the basis of all instruction in

speech in this school.1 The result of his visit was the employment

of the son, Alexander Graham Bell, as a special instructor in the

school for a period of three months.”

The scene at Chautauqua, June 29th, 1899, on the occasion of the

last meeting of the National Association of Elocutionists which he

attended, was impressive beyond ability adequately to be described

in words. In the commencement of the ever memorable address on

“Fundamentals of Elocution/’ delivered by Prof. Bell, he tersely

stated:

“Elocution is an art: hence its practice is more important than its

theory, * * * *. The requirements of Elocution are: first, that the

speaker should be heard without effort on the hearers’ part; second,

that the utterance of words and syllables should be distinct and

unambiguous; and third, that vocal expression should be in sympathy

with the subject. In common practice we find that these requirements

are conspicuously wanting.”

At the close of the address, no less than a dozen members

successively arose to pay tribute to the speaker.

“It seems to me,” said the first, “not only fitting, but a very

natural thing for this audience to desire to express its feeling,

and I rise to move a vote of thanks to our distinguished benefactor

of past years, who has so honored us today, for the magnificent

exemplification which he presents in his own person of the benefits

to be derived from our work. When a man so glorious in years, and in

work, can stand so magnificently before this assembly, he presents a

most inspiring example for emulation. And it is with a feeling of

deepest gratitude in my heart for what he has done today in thus

honoring us, and what he has done for elocution in the past, that I

move, on behalf of this audience, a vote of thanks to Prof. Bell for

having come before us and given us this treat.”

The vote was taken by an enthusiastic rising of the entire assembly.

Another speaker said:

’“The Horace Mann School.”

“In the presence of the true, the beautiful, and the good, there

seems to be an atmosphere in which all personal differences sink out

of sight. Standing as we do before one whose life has been a

benediction to our cause, the desire for victory in any lower sense

of that term, seems to pass entirely away. Since each one of the

preceding speakers has drawn some moral from this present occasion,

I should like to offer my contribution. We regard the speaker of

today so highly because he has stood against clamor, against

so-called public demand, against the exigencies of varying

occasions, and has upheld the truth, simplicity, and integrity of

purpose, * * * *. Let us then take from this inspiring hour today,

the lesson from the life of the speaker, who, against almost

insuperable obstacles, has stood firmly for the right, and in the

end, like Dr. Russell, and Mr. Murdoch, is crowned a Victor.”

These, and other like remarks, were forcibly and touchingly

supplemented by the able editor of the official organ, who wrote in

regard to the occasion:

“‘Consecration’ and ‘benediction’ were words frequently heard at the

Chautauqua convention of Elocutionists. These words were used in

connection with the presence of Alexander Melville Bell, who, at the

age of eighty, stood upon the platform and delivered an address with

a grace of manner, pureness of enunciation, and distinctness of

articulation, surpassed by no other speaker at the convention.

Bell’s presence permeated and dominated everything, * * * *.

Alexander Melville Bell is the greatest living elocutionist. To

attend the convention, he made a special journey of two thousand

miles, foregoing the coolness and quiet of his distinguished son’s

summer Canadian home. Well might the members of the National

Association of Elocutionists rise to their feet when he entered the

hall, and well might they congratulate themselves on being

privileged to attend a session that is a historical event in

American elocution. Words can only very inadequately describe the

scenes at the Bell session. On the platform stood an elocutionary

patriarch, whose discoveries, inventions, and writings have

vitalized, purified, and glorified the English language: uttering

words of counsel, and pronouncing a benediction. There he stood,

erect, reposeful, vigorous, graceful: his bearing, gesture, voice,

articulation—all models worthy the study of those that aspire to

oratorical excellence. Before him sat many of the leading

elocutionists of America, hushed, attentive, impressed—so impressed

that men shed tears, and when a resolution of thanks was moved,

voices were choked, and the pauses of silence were more eloquent

than were the words. The sentiments of the entire assembly were

voiced by a speaker who said that he consecrated himself anew to his

profession, and that hereafter he never could, or would apoligize

for being an elocutionist, * * * * The presence of Alexander

Melville Bell at the Chautauqua convention has leavened the whole

elocutionary lump, and has put a heart into the National Association

of Elocutionists.”

Here was a spontaneous recognition of the professional life work of

a Master truly great. Among many other tributes rendered, I will

here add only that of two of his pupils, one of whom, now a leading

elocutionist, thus sums up Mr. Bell’s elocutionary labors:

“‘An Uncrowned King,’ the phrase sprang to my mind as Prof.

Alexander Melville Bell entered his reception room one summer day.

It was my first interview. I had cordially been invited to come to

Washington to review ‘Principles of Elocution,’ and ‘Visible

Speech,’ with the author. Many years before I had studied the

‘Principles of Elocution,’ and had used it with my pupils. The

assent of the mind to truth is one of the keenest of intellectual

pleasures, and I find myself constantly, in teaching from his book,

feeling that enthusiastic thrill. There have been many elocution

books written since first his appeared, but where they depart from

him, they are wrong, and where they follow, they are not original.

He cut the way through the forest, by giving clear principles, not

mere rules, and the keen ear that could detect the faintest

departure from right speech, which made him the great inventor of

the Visible Speech Alphabet, served him also in his analysis, and

interpretation of dramatic emotion. His own voice was rich,

melodious, and beautiful, even at eighty, while his enunciation of

course was that of a past master of speech. In Prof. Bell’s books

the serious student finds the explanation of all his difficulties,

and the sure guide to the eradication of his defects. The lawyer,

the lecturer, the politician, the preacher need just the aid that he

gives—for with him, the art of elocution is worthy of the best

effort of all voice uses. And all such need to study its principles.

* * * * A great and noble life has passed onward. But in his books,

his spirit speaks to us, and many generations still.”

The other, one of Prof. Bell’s most ardent and efficient desciples

of his system of “Visible Speech,” which constitutes the scientific

basis of his success as a master of speech:

“The invention of Visible Speech is one of the world’s greatest

benefactions, and has given mankind the only possible Universal

Alphabet. It has a physiological basis. Each symbol means a definite

position of the organs of speech, which, if correctly assumed,

produces a definite result. Every sound possible for the human voice

can be represented by these symbols. There is, therefore, no

language nor variation of language in dialect, or even individual

idiosyncracy, which cannot be represented by Visible Speech and

reproduced vocally by any one knowing the system.

“In consequence of this fact, through Visible Speech one may learn

to speak every language as it is spoken by the Nations of all

classes. Missionaries learn through Visible Speech to speak

accurately the language of high caste, as well as that of the lower

classes, thereby greatly increasing the scope of their influence.

Through its perfect mastery impediments of speech can be

successfully treated, and the hopeless handicap of stammering,

stuttering, and like blemishes disappear as if by magic. A knowledge

of it furnishes the very best vocal training, because its symbols

compel perfect precision of muscular adjustment for their accurate

reproduction in tone, and so presents a system of vocal gymnastics

whereby the greatest skill and flexibility of the vocal organs is

attained. The effect produced upon the voice and speech is analogous

to that obtained for the body by the varied exercises in use for

physical training. It is in fact invaluable to both speakers and

singers.”

The following tribute paid Prof. Bell by one of his most eminent

professional colleagues, constitutes a recognition of his

exceptional mastership of the Science underlying his methods of

acquiring perfection in the art of speech, such as has come to very

few, if any elocutionists, from well recognized authority:

“I retain a vivid remembrance of meeting Mr. Alexander Melville Bell

before leaving England. I was much struck with the purity and charm

of his speech. It was a revelation to me. His utterance seemed to

combine the easy, graceful intonation of the talk of a cultured

actress, with the strength and resonance that should characterize

the speech of a man, and though finely modulated, it was without a

suggestion of affectation, either as to matter or manner. I had

never before, and I do not know that I have since, heard English

spoken with the ease and delicate precision that so distinctly

marked the speech of Mr. Bell. His clean-cut articulation, his

flexibility of voice, and finely modulated utterance of English, was

an exemplification of what efficient and long continued training of

the vocal organs will do for human speech, and how charming the

result.”1

The scope of Prof. Bell’s thoughts, however, were not wholly

absorbed by his profession, as t'he list of publications here

appended, and the honors bestowed upon him, show. He was also

thoroughly versed in the Science of Phonetics and Stenography;

likewise an ardent advocate of amended Orthography, deeply

interested in various forms of Social Science, and possessed of

considerable poetic gift. Whilst not an electrician, he may no

doubt, however, have contributed somewhat towards stimulating his

surviving son in the incipient conception of the Telephone by having

offered a premium to whichever of his sons should construct the most

effective articulating apparatus: one of which of these earlier

speaking devices was recently yet in possession of the family.

The amelioration of the condition of discharged convicts, and

provisions for the care of neglected and dependent children, deeply

interested him, and to the latter trend of his sympathies is due the

establishment, at Colonial Beach, Virginia, of the “Beil Home,”

which has proven to be one of the most efficient benefactions for

poor children in the District of Columbia.

Among the objects Mr. Bell seemed to take special interest in

promoting, was the work of the Volta Bureau for the increase and

diffusion of knowledge relating to the deaf, founded by his son, Dr.

Alexander Graham Bell. Not only did he contribute generously towards

the architectural attractiveness of the building, but donated to the

Bureau his entire stock of publications, including stereotype

plates, and also his valuable copyrights, increasing thus its

efficiency: this, and the service which his Visible Speech device

rendered in acquiring speech and the art of speech or lip-reading,

endeared him to many deaf, notably among them, Helen A. Keller,

whose love and regard for him he always spoke of most appreciatingly.

Although Mr. Bell had permanently left Ontario nearly a quarter of a

century ago, true to his nature, he retained up to the last a strong

affection for his many Canadian friends. And the citizens of

Brantford showed their appreciation of this devotion at each

recurring visit Mr. Bell paid to his former home. On the occasion of

his presence there during the Dominion tour of the Duke and Duchess

of Cornwall and York, October 14th, 1901, when the Royal couple

stopped enroute in Brantford, Mr. Bell was accorded the honor of

presenting, on behalf of the City, to His Royal Highness, the Duke,

a handsomely mounted long distance Telephone outfit, furnished by

the Bell Telephone Co. On being presented to His Royal Highness, the

latter cordially shook hands with Mr. Bell, who then ifnpressively

said:

“On behalf of the City of Brantford, I have the honor of presenting

to your Royal Highness, this Telephone as a Souvenir of your brief,

but

highly prized visit to the ‘Telephone City.’ May all our telephones

and telegraphs continue to bring us only glad tidings of your happy

progress throughout the British Dominion, where each province vies

with the others in the warmth of its welcome to his Majesty’s

representatives, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York. Health

and long life to King Edward the Seventh, and to his Queen. God save

the King and Queen.”

Both the Duke and the Duchess expressed themselves as highly

gratified 011 receiving so singularly appropriate and useful a

present.

Nor were friends and relatives 011 the distant Pacific Coast, and in

remoter Australia, forgotten. Nothing seemed to gratify Mr. Bell

more than the repeated evidence by letter of their continued

remembrance.

The greatest charm, however, of Prof. Bell, was the social sphere of

his home. To all, rich or poor, high or lowly, Mr. Bell was always

courteous and kind. He proved himself a devoted father, a model

husband, and exemplary grandfather, great grandfather, uncle, and

cousin. Making available provision dur,-ing his lifetime for

relatives nearest and dearest to him was characteristic of his

constant thoughtfulness. Mr. Bell twice married most happily; first,

1844, Eliza Grace, the refined and accomplished daughter of Surgeon

Samuel Symonds, mother of his surviving son, and beside whose

remains now lie those of her distinguished husband. His second

marriage, 1898, to Mrs., Harriet G. Shibley, who survives him,

proved a source of rare connubial felicity. The filial devotion

accorded Professor Bell by his immediate family, was simply ideal,

of a nature so perfectly exemplary and beautiful, that any attempt

to speak of his family relations truthfully would be invading the

sanctity of a model home. All who have been privileged to be near

him, could not otherwise than become deeply sensible of the

ennobling and refining influence of his wholesome personality. To

sit at his board, and occasionally enjoy the elocutionary “bouts”

between him and his accomplished brother, in which, at times, they

were joined by his equally gifted son, as they bantered each other

with recitations from Shakespeare, or other favorite dramatists and

authors, not infrequently dialectic and in Gaelic, was an

intellectual treat few mortals can ever have enjoyed with such

recognized elocutionary masters as principals. The humor, prompt

retorts, and fire that at such times would fly from one to another

was something akin to an array of batteries emitting electric

sparks, and would baffle accurate portrayal. It can truthfully be

said of Prof. Bell, that a kindlier face than his has seldom been

seen, especially among so-called more thoughtful scientists. His

optimism constantly made itself manifest by the evident delight he

showed in embracing every possible opportunity in giving delight to

others. The rare faculty of “making the best of everything,” seemed

spontaneous with him. While positive in his conceptions of the

beautiful and true, uncharitable criticism seemed foreign to him.

His mind seemed utterly free from malice and bent on doing all the

good he could. His sphere was one of marked content and radiant good

will. Although often earnest in mien, no one has ever been heard to

say that they saw Mr. Bell really angered. Rage was foreign to his

nature. He could calmly look upon a furious storm, admire the force

of wind and wave, and it seemed to harbor no terror to him. Scenes

of unruffled wave, where steamer and sailing craft silently passed

along on their errands of service to fellowmen, such as greeted him

from his seat on the embankment in front of his residence at

Colonial Beach, were equally if not more to his liking than the

commotion of antagonising elements. By nature he was averse to the

boisterous, and courted rather scenes of silence and gentleness. To

see him ensconsed in his chair on the well shaded vineclad veranda

of his riverside home, at times reading and smoking, or watching the

brooding, ever chattering sparrows he had encouraged to build their

nests along the inner eaves, was to see incarnated content upon his

countenance. Always fond of domestic animals, in later years he more

especially liked to keep pets, and loved to feed his dogs, birds,

and fishes himself. In his city den or studio, he could while away

hours patiently analyzing the speech of his parrot, and determining

the notes of his canaries and mocking birds, or marvelling at the

ceaseless and graceful evolutions of the fishes in his aquarium.

These pets, together with flowers of all kinds, not onl^afforded him

congenial companionship and diversion, but also a constant,

delightfully interesting study.

Prof. Bell was honored with the fellowship of the Educational

Institute of Scotland, and with that of the Royal Scottish Society

of Arts, the latter of which, in special recognition of the system

of phonetic shorthand he devised, awarded him in addition its Silver

Medal. In 1885 he was likewise elected a fellow of the American

Association for the Advancement of Science; he was an active member

of the Modern Language Association of America, Anthropological

Society of Washington, and the National Geographic Society, a life

member of the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech

to the Deaf, an honorary member of the National Association of

Elocutionists, etc., etc.

Despite his advanced years, Prof. Bell retained his mental vigor and

general good health to a remarkable degree. In order to enjoy each

other’s society as much as possible, the father, towards the last,

assented to take up his abode with the son, 1331 Connecticut Avenue,

N. W., where, surrounded by every possible comfort, Mr. Bell

received the tireless attention of a devoted wife, loving son,

daughter-in-law, and faithful attendants. As the last summer

approached, Mr. Bell longed to go to his favorite riverside

homestead, but it could only be for a brief period when his

enfeebled condition made it desirable he should return to his son’s

residence in Washington, where, August 7th, 1905, surrounded by his

immediate family and a few close friends, he gently passed away.

Truly, like Gladstone will Alexander Melville Bell also long be

remembered as “The Grand Old Man.”

The interment took place at Rock Creek cemetery, the Rev. Dr. Teunis

S. Hamlin officiating, and the following distinguished associates

serving as honorary pallbearers: Hon. James Wilson, Secretary of

Agriculture; Dr. William T. Harris, United States Commissioner of

Education; Hon. H. B. F. MacFarland, Commissioner of the District of

Columbia; Prof. William H. Dali, of the Smithsonian Institution; Mr.

Ainsworth R. Spofford, first Assistant Librarian of Congress; and

Dr. A. L. E. Crouter, President of the American Association to

Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf.

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PROFESSOR ALEXANDER MELVILLE BELL, P. E. I. S., F.

R. S. S. A., A. S., Etc.

*ELOCUTION, VOCAL PHYSIOLOGY, AND DEFECTS OF SPEECH.

1845. Treatise on the Art of Reading.

1849. A new elucidation of the Principles of Speech and Elocution.

1852. Principles of Elocution: “The Elocutionary Manual.”

1852. The Language of Passions.

1852. Expressive Reading and Gesture.

1853. Observations on the Cure of Stammering.

1854. Lecture on the Art of Delivery.

1858. Letters and Sounds. A Nursery and School book.

1860. The Standard Elocutionist. (210th thousand issued 1899.)

1863. Principles of Speech and Dictionary of Sounds.

1863. On Sermon Reading and Memoriter Delivery.

1866. The Emphasized Liturgy.

1879. On Teaching Reading in Public Schools.

1880. The Faults of Speech.

1886. Essays and Postscripts on Elocution.

1890. Speech Reading and Articulation Teaching.

1893. Speech Tones.

1894. Note on. Syllabic Consonants.

1895. Address to the National Association of Elocutionists.

1896. The Sounds of R.

1896. Phonetic Syllabication.

1897. The Science of Speech.*

1899. Notations in Elocutionary Teaching.

1899. The Fundamentals of Elocution. ,

VISIBLE SPEECH AND PHONETICS.

1866. Visible Speech: A New Fact Demonstrated.

1867. Visible Speech: The Science of Universal Alphabetics,

(Inaugural Ed.)

1868. English Visible Speech for the Million.

1868. Class Primer of English Visible Speech.

1869. Universal Steno-Phonography on the basis of Visible Speech.

1870. Explanatory Lecture on Visible Speech.

1881. Sounds and their Relations: Revised version of Visible Speech.

1882. Lectures upon Letters and Sounds, and Visible Speech, before

A. A. A. S.

1883. Visible Speech Reader.

1885. University Lectures on Phonetics.

1886. English Line Writing on the basis of Visible Speech.

1889. Popular Manual of Visible Speech and Vocal Physiology.

1893. English Visible Speech in Twelve Lessons.

1903. Lecture on Visible Speech, in New York.

NEW ORTHOGRAPHY OF ENGLISH.

1888. World English: The Universal Language.

1888. Hand-Book of World English.

PHONETIC SHORTHAND.

1852. Steno-Phonography, (Silver Medal Awarded to Author for this bv

’ R. S. S. A.)

1854. Shorthand Master book.

1855. Popular Stenography: Curt Style.

1857. Reporter’s Manual and Vocabulary of Logograms.

1892. Popular Shorthand.

MISCELLANEOUS.

1851. What is to become of our Convicts?

1857. Common sense in its relation to Homeopathy and Allopathy.

1869. Colour: The Island of Humanity. A drama.

1891. Address to members of the Senate and House of Representatives.

You can download a pdf of this article here

You can also download his book Visible Speech here

|