|

On September 17, 1780, there was

born at Stoir Point, Assynt,

Sutherland, Scotland, a child who was destined to play a wonderful part in

the lives of many of his countrymen—this was Norman McLeod. His people

followed the time-honoured occupation of fishermen and

cultivators of the soil. The McLeods are

a very ancient Highland family, and received a charter from David II to

the lands of Assynt. They also held lands in Skye and Lewes. It may,

therefore, be concluded that Norman’s people were inhabitants of Assynt

for some centuries. It was McLeod, Laird of Assynt, who caught and

betrayed Montrose in 1650. It was another McLeod, one Malcolm, who was

guide to Prince Charlie during his wanderings in the Hebrides. He,

however, belonged to the Skye branch of the McLeod family.

The people of Caithness and

Sutherland took little part in the affair of 1745, as the Earls of these

respective counties were Royalists, and this acted as a check to the

Jacobite proclivities of their clansmen. The rent-crofting system was also

a little late in appearing in these counties. The Earldom of Sutherland is

one of the oldest in the kingdom. There were Thanes and Jarls in Caithness

and Sutherland from the days of the early Nordic invasion in the ninth

century. The whole northern coastline of Scotland and much

of

the interior was Scandinavian territory for centuries. In 1228 Alexander

of Scotland created William, Jarl of Sutherland, as first Earl of

Sutherland under the Scottish Crown. As a consequence of this long

dominance of the Nordics, the people of Caithness and Sutherland and all

the Hebridean Isles are as much Nordic as they are Celtic. This explains

the large number of fair and red-haired, high cheek-boned, grey-eyed

people found in these localities.

In

1758 Assynt was purchased by the Earl of

Sutherland, and thus the McLeods lost their footing upon the mainland of

Scotland. About the same time the estates of Sutherland fell to a female

of the line. This lady in 1785 married an Englishman named Leveson-Gower,

and in 1833 he was created the first Duke of Sutherland. Under him, from

about 1800-1840, began that series of cruel evictions in Sutherland known

as the " Sutherland Clearances."

SUTHERLAND CLEARANCES.

The 1745 rebellion made an enormous

difference to the Highland clans. Previous to 1745 no clansmen could be

evicted from their homes, as they held them by feudal right; while the

land was the common property of the tribe or clan, and hence of no single

individual. The affair of 1745 swept all feudal rights out of existence.

The lands were then invested by Sheepskins (deeds) in the loyal chiefs,

landlords, and successors of the rebels. The government knew it could

control the landlords who held their lands from the Crown, but it could

not control thousands of clansmen who held their lands by feudal right.

The people felt they were wrongfully dispossessed of their lands, but

being nominally rebels—for they were all classed alike—they could not

resist. The common people have never admitted the legality of the act, and

to this day they claim the land as theirs, even though it may have passed

by purchase to several owners.

The people of Sutherland had a

double grievance. They took little or no part in the rebellion. They

looked upon the Earl as their father, into whose hands they had committed

the keeping of their lands, as for mutual protection. He had merely to say

the word and every man would rush to arms in protection of their common

property. Now he had disowned them, threw them out of their homes, and

razed them to the ground so as to prevent a reentry. It is said that sick

and dying people were forcibly carried out and left to perish. So terrible

were the harsh scenes of these days that they have indelibly burned

themselves into the memories of the people, and they have never forgiven

the Highland Lairds. To make matters worse, many of the men, whose homes

were being burnt, were at the time fighting the battles of their country

under Wellington at Waterloo. All this work was carried out by factors or

land agents. They were strangers who had no sympathies with the local

people. Most of them were Englishmen, and so the words "factor" and

"Sassenach" became anathema to the people. By such means are ill feelings,

hatreds, and national antipathies aroused which centuries cannot

eradicate.

The local poets of the day satirized the factors in

song and story. One popular ditty ran as follows :—

Or yet a factor, fat and proud,

Burning a Hieland bothy;

Swearing at the hapless crowd

Whom he has made unhappy.

Oh; heavens hide me from that sight,

A father void of means,

Compelled to view his burning home,

His weeping wife and we-ans.

A theory put forth by those in

authority at the time was that the evictions were an economic necessity.

There were too many people settled along the river valleys or Straths for

their size or fertility. Hence, more or less, poverty and starvation faced

them every winter. They had plenty hill pasture for their stock during the

summer time, but not sufficient winter keep. There may have been some

truth in this theory, but it does not appeal to one as being a good reason

for depriving them unrewarded of their age-old inheritance. The chiefs of

old acquired their lands not by payment, but by discomfiting in battle

some local chief or tribe; but the surviving people were not deprived of

their land, only their allegiance was transferred to the new chief; while

his warriors were settled amongst them. This was their feudal right, so

that economic sophistication cannot enter into the question unless by

mutual consent and compensation.

The Sutherland family at this time

practically owned the whole county extending to about 1,200,000 acres. The

people were permitted in some instances to form new settlements along the

coast and find their living from the sea. The whole interior of the county

was depopulated. Hundreds perished from cold and hunger. Hundreds more

trekked to the neighbouring counties or towns, or were shipped as so much

lumber to the wilds of America. It was a period of national disgrace and a

blot upon British history. Not even rebellion could justify the cruelties

and hardships of these sad times. The Highland people have never forgotten

them, while the wail of 1745 and its consequences still reverherates

around the world.

Norman McLeod and his people were

probably amongst those who suffered in those barbarous days. The sword and

dirk had been cast aside, and men were no longer required to fight for

their chiefs. Swords must now he converted into ploughshares and brawn

into brain. Yellow Gcordies (sovereigns) now served all purposes. They

made foes; they made friends; they made battle; they made slaves; yea,

even they were not beyond the attempting of Simony. Norman was a lad of

parts. He cultivated brain, and observing the ease and comfort of the

local parish clergyman he thought that he too could fill that position.

Indeed, it is surprising to witness the number of Celts in the

British Isles who adopt the Church as their career. Visit the principal

cities and towns in them, and everywhere one finds Celts filling the

principal pulpits in the land. As ready speakers they cannot he excelled

while, where persistence and sound judgment are necessary, they have no

superior. They do not appreciate being hewers of

wood or drawers of

water, hence they strive to leave such work for less ambitious

individuals. Norman went to Aberdeen, and in due time became a graduate in

Arts of that ancient seat of learning. One may well wonder how lads with

no money could enter a University. The old proverb has it "that where

there is a will there is a way." Many poor lads in Scotland have passed

through a brilliant college career with the slenderest of incomes earned

while attending college. The slothful say that they carry a sack of

oatmeal on their backs to the nearest University town, and turn to this as

the ox to his stall when hunger compels. The picture is overdrawn, but

there is a germ of truth in it. They work continuously at whatever they

find convenient, and learn their lessons by the street lamp-post. They are

policemen, clerks, teachers, labourers, shop-keepers, indeed, anything by

which they

can arrange to attend classes and eke out an existence. Once they set

their minds upon some career there is no denying them. A few fall by the

way, but that is common to all victories. Of such stuff was Norman. He

worked at any suitable job during the College session. That over, he found

no difficulty in finding work as a school teacher or private tutor during

the vacations. He filled various offices in Ross and Sutherland as parish

schoolmaster, while some other ambitious lad filled his position during

the session.

RELIGIOUS AWAKENING

During all this time he was

undergoing a process of religious awakening. Under the old Church of

Scotland dispensation every parishioner had the right of partaking of

Communion and the having of his children baptized. The conduct of some of

the clergy and communicants jarred upon Norman’s rising intelligence. He

was naturally gifted with the power of speech and also with the courage of

his convictions. These qualities led to his rebuking in public such as

came under his displeasure as persons who were "eating and drinking

unworthily." In choosing a school in which to study theology he selected

Edinburgh. The latter city has for ages been a great seat of learning, and

draws to its schools some of the best brains in the British Isles. Here

his religious awakening still further deepened, so that the whole of his

spare time was occupied in missionary work and preaching. Various

charities and churches have established missions in and around the city,

so that a capable and willing student can be readily occupied all the year

round. Professors of Divinity, like all other mortals, are weak and

fallible. They may succeed in hiding their weaknesses from the common

herd, but the keeneyed, mentally-alert, observing student can and does

penetrate the closest of veils. In his third and final year at the

Divinity Hall Norman is said to have found fault with and rebuked one of

his teachers owing to his loose mode of life. For this grave offence he

was rusticated, and so became what is known in Scotland as a "Stickit

Minister." This term in Scotland is generally applied to any professional

man who has failed to qualify or to pass the necessary examinations. It

was an approbrious but a useful weapon, for it lashed many a lazy student

to diligent study.

MARY McLE0D.

Norman, on being rusticated,

returned to Assynt a disappointed man. There were some compensations.

however. Ever since school days he and a neighbour girl named Mary McLeod

were great friends. They were classmates. and often times vied with each

other as to which would be top of the class. Norman, with that gallantry

of the Celt towards women, never disputed Mary’s right to be dux. If he

were second that was sufficient. As the years rolled on they continued

their mutual interest. Every year as Norman left for College Mary had

always prepared such presents as her limited purse could afford. They

might be socks or jumpers, shirts or plaids, carded and knitted by her

hand. These were love-philters of a kind, and the gallant Norman readily

responded to them. Letter-writing in those days was somewhat uncommon, at

least in remote districts. The post was irregular, very costly, and not

established as we know it. Rowland Hill had not as yet arrived, and so

most letters in those northern districts were sent by chance carrier. It

was quite common for people from the most northerly point of the mainland

to travel on foot to Aberdeen, Edinburgh, or Glasgow, a distance of from

200 to 400 miles. One Christmas Mary and a companion are said to have

walked from Assynt to Aberdeen to carry presents to her beloved Norman.

Such devotion was irresistible, and Norman was responsive in every fibre.

Any class prizes or appointment success of Norman were equally appreciated

by Mary. He was Gold Medallist in the Moral Philosophy class, and this

trophy Mary treasured as a brooch until death parted them. There was only

one Presbyterian Church in Scotland in his day, and its doors were barred

to him; but as a University graduate he could easily obtain a parish

school appointment. Mary and he discussed the situation, and it was agreed

that if Mary would turn housekeeper Norman would become a dominie. The

bargain was sealed, two life-long lovers were united, and Norman became

parish schoolmaster.

REV. WM. McKENZE.

The minister of the parish at the

time was the Rev. Wm. McKenzie (1765-1816). It is said that Mr. McKenzie

was almost everything a clergyman ought not to be. He was addicted to

drink, and frequently absented himself from duty for weeks on end.

Possibly his people were somewhat to blame for some of his lapses. It was

the custom then for every household to have some whisky in the cupboard

for the use of visitors. Hospitality demanded that visitors be

entertained, and what more convenient than the whisky bottle. The minister

was the honoured guest in every home and frankly accepted such as was

placed before him. As a consequence he was almost compelled to drink from

six to twelve glasses of whisky per day on such days as he went visiting.

The people knew of his weakness, but loyalty and the awe of his office

prevented them from making any complaint. As a man and neighbour he was

all that could be desired, and these things in the estimation of his

people covered a multitude of sins. Habits of this kind were not unknown

in comparatively recent times in New Zealand. divine, who shall be

nameless, resolved to renounce all forms of liquor and became an advocate

of total abstinence. One day he had occasion to visit a parishioner, and

the laws of hospitality had to be obeyed. The good lady of the house

prepared a cup of tea for him. As the day was cold, and the divine aged,

she added some whisky to his tea. The good divine, suspecting nothing,

drank the tea, and turning to his hostess said, Lord, woman, that’s

whisky." "Never mind, dear doctor, the day is cold, and you need it." The

habits of generations are not easily eradicated, whether in land—holding

or social customs.

Owing to the circumstances

surrounding Mr. McKenzie, the people desired Norman to hold religious

services. They knew that he had been a missionary in Edinburgh for three

years and accustomed to preaching, so that in Assynt he would he merely

continuing the work he had begun at College. It was the custom, however,

in the Highlands in those days for young Christians to remain silent.

Preaching was an ordinance reserved for the trained clergy or aged

Christians who were approved of by the clergy. Mr. McKenzie had not given

his approval to Norman as a preacher, and hence he deemed it courteous to

remain silent.

WHEN ZEAL VIES WITH ZEAL.

in 1806 the Rev. John Kennedy was

appointed as assistant to Mr. McKenzie of Assynt. Mr. Kennedy belonged to

a family of divines who were remarkably prominent in the northern

counties. He was a young man of uncommon piety, and soon made his mark as

a leader in the church. Thoroughly evangelical and profoundly interested

in the spiritual and temporal welfare of his people, he was the right man

for the Assynt parish. A wave of religious enthusiasm swept over the

district and rapidly spread to the adjoining counties. His fame was

somewhat similar to that of the Great Apostle, for almost every parish in

the north sent him the message: "Come over into Macedonia and help us."

All

this religious

enthusiasm aroused the zeal of Norman. Contrary to the wishes of Mr.

McKenzie and Mr. Kennedy, he began to preach. To enable him to do so he

cut himself adrift from the Church of Scotland, and set up a kind of Free

Church of his own. In this he anticipated the Disruption of 1843. The

Church of Scotland was a State institution to which the government or some

local landowner had the sole right of selecting a clergyman. The people

had no voice in the election of their minister. In this they were treated

as children, or as slaves, who must accept that which their masters were

pleased to offer them.

The time was opportune, and

apparently Norman seized the opportunity. He soon gathered a large

following, and as a consequence there was division in the parish church.

He had a marvellous gift of speech, an attractive manner, and a clearness

in presenting truth that was irresistible. He paraded the foibles of the

clergy and the autocratic methods of the church proprietors so clearly

that the people were aroused. Neither Mr. McKenzie nor Mr. Kennedy could

stem this revulsion of feeling. The facts were so patent that Mr. Kennedy

elected to depart for pastures new. Norman held the field and the parish

church was emptied.

Mr. Kennedy subsequently became

parish minister of Kilearnan, Ross-shire, and there he became the father

of that great and distinguished divine, the Rev. Dr. John Kennedy of

Dingwall. It is curious to relate how in after years this Dr. Kennedy

became a zealous Free Churchman. Apparently he saw things much as did

Norman, and followed in his footsteps.

Dr. Kennedy and the Rev. Dr. John

Macdonald, who was known as the "Apostle of the North," laboured in two

adjoining parishes, the one in Dingwall and the other in Ferintosh. These

two men were literally worshipped in their day by the people of the

northern counties. Such was their fame as preachers that people travelled

many miles to hear them preach. During their summer peregrinations at the

various Sacrament seasons in the north, numbers of people followed them

from parish to parish as if their salvation depended upon the presence and

words of these men. We may truly say that in a religious sense these two

men were magicians, and the people were helpless.

In his book, "The Fathers of

Ross-shire," Dr. Kennedy, in writing of Norman, says :-.--

His power as a speaker was such that he could not fail

to make an impression, and he succeeded in Assynt and elsewhere in drawing

many people after him. His influence upon those whom he detached from a

stated ministry was paramount, and he could carry them after him to almost

any extent. Some of the pcople of Assynt were drawn into permanent

dissent. Some, even of the pious people, were decoyed by him for a season,

but eventually escaped from his influence. The anxiety and disappointment

of this trying season were particularly painful to my revered father.

From the above testimony it is

apparent that some at least of the clergy thought that they alone could

present the truth. Norman was evidently a magician, such as in subsequent

years were two other Ross-shire divines.

Lay-preaching was not a profitable

occupation where a family was concerned. Assynt was a poor district and

money was scarce. Gratitude and popularity he had in abundance, but they

failed to provide him with food and shelter. In 1815 the parish school of

Ullapool fell vacant. Norman applied for the post and was appointed.

Ullapool was in the parish of Lochbroom, almost adjoining to Assynt, and

the Rev. Dr. Ross was the parish minister. In those days the parish

minister was virtually the master of the parish teacher. Dr. Ross was a

man of violent temper and autocratic manners. While teaching here a son

was born to Norman, and as Dr. Ross was neither evangelical nor popular in

the parish Norman decided that he would have his son "John Luther"

baptized by the far-famed Rev. Lachlan McKenzie of Lochcarron. To this end

he and his wife carried their child over bog and moor some 50 miles to

Lochcarron Manse. On arriving, whom should they meet but their own

clergyman, the Rev. Dr. Ross. He forbade the Rev. Mr. McKenzie to baptize

the child, as Mr. McLeod, as parish teacher, had not asked him (Dr. Ross),

the parish clergyman, to perform the ceremony. Norman’s journey of about

100 miles was of no avail, and he returned to Ullapool very crestfallen.

Shortly thereafter Dr. Ross returned

to his parish, and decided to punish the teacher for his want of decorum

towards the parish minister. To this end he found fault with Norman for

certain religious views he taught the children. Norman was patient, and

endured the reprimand with great composure. His teaching, however, went on

along the old lines. Then Dr. Ross secured the reduction of his salary by

one-half. This was the signal for rebellion. Norman defied him and

ultimately resigned his situation. Then he began preaching, and in a short

time the parish church was empty, and ever afterwards remained divided. At

this time the parish clergymen in the north were mercilessly castigated by

the people. A general rot set in, their people left them, and they have

never returned. This was Norman’s second attack on the Church of Scotland,

and so it was unlikely that further parish schools would be open to him.

In this dilemma he turned to his old occupation of fisherman, and for two

seasons was skipper of a herring boat fishing from Wick in Caithness. Here

he was in his element, for there were several hundreds of his countrymen

and women engaged in the same occupation. None of these people would work

on the Sunday, so Norman established himself as the local preacher for all

the Gaelic-speaking people. As a result he became very popular and well

known in Caithness and Lewes, as well as in his native Sutherland and

adopted Ross-shire.

Some seasons the herring fishing is

a remarkably profitable occupation. so that in six weeks to two months

crews of from four to six men can earn sufficient, with the aid of their

crofts, to live in moderate comfort for the remainder of the year. Norman

was successful as a fisherman, and decided to return to Stoir and resume

crofting and fishing as his life’s occupation.

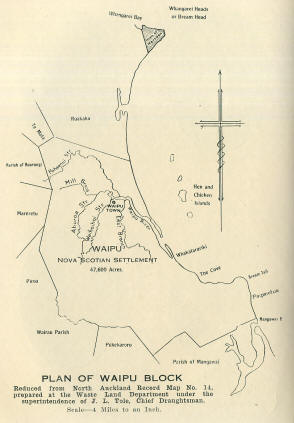

Plan of Waipu Block

The old adage has it "that man

proposes and God disposes." The "factors" became busy with their

clearances. There was wailing in the land, and men’s eyes were turned

towards America. The people were being forcibly driven from their homes,

and in their desperation cursed the government, the lairds, the caora-glas

(grey sheep) and the "Yellow Geordies." They said :—

For thee insatiate chief, whose

ruthless hand

Forever drives me from my native land;

For thee I leave no greater curse behind

Than the fell bodings of a guilty mind.

Or what were harder to a soul like thine

To find from avarice thy wealth declined.

The mills of God grind slowly but

surely. The Shennachies (wise men) declared that retribution would come. A

woman betrayed them and a woman would be the avenger. These Shennachies

were credited with the powers of second sight. They prophesied that a time

would come when ruin would overtake the Highland Lairds. That men and

women would come from the far west who would cause dismay amongst the

perpetrators of these cruelties. That the God of War would ride rough-shod

over the land, leaving only the shrill cry of the curlew or the moan of

the shochat (lapwing) to be heard in the glens.

Ever since those days some people

have been looking for the fulfilment of these prophesies, and they have

not been entirely disappointed. Owing to the vicissitudes of fortune and

the exigencies of the Great War, the Highland Lairds to-day own only a

part of their ancient territories. An Assynt boy, who is an American

engineer, owns the Assynt parish. Other natives from abroad, and also some

strangers, own several of the other parishes. Many of the old Highland

Lairds have lost their estates throughout the Highlands, so who can deny

the possibility, nay the probability, of the truth of the Shennachies’

second sight. If one may judge from the economic and political turmoil of

the day, it looks as if the great landlord system of the British Isles is

doomed to extinction. What the next phase of the land question may be we

leave for the Shennachies to foretell.

One of the great Lord Bacon’s

aphorisms was: "it is an evil hour for the State when its treasures and

money are gathered into few hands."

The poet modified these words into

the lines—

Ill fares the State, to hastening

ills a prey,

When sheep do multiply and men decay. |