GENERAL INTRODUCTION

The papers embraced in this and the subsequent

volumes consist of documents, transcribed in Holland, illustrating the

services of the Scots regiments to the United Netherlands during the

long period of more than two hundred years for which the Scots Brigade

formed part of the permanent military establishment of the Dutch

Republic, except for an interregnum of about ten years between the

Revolution of 1688 and the Peace of Ryswick, when these troops were in

British pay, and in the direct service of Great Britain under King

William in. They consist of two classes: (a) Documents from the

archives lof the United Netherlands at the Hague, relating to part of

the sixteenth, the seventeenth, and the eighteenth centuries; and (b)

the Rotterdam Papers, a collection of regimental papers which were

kept in the regiments, and afterwards preserved among the records of the

Scots Church at Rotterdam, from which they were removed to the municipal

archives at the Town Hall, where they still remain. In the first volume

are [embraced the documents from the Dutch Government archives relating

to the period prior to the service of the Brigade in treat Britain after

the Revolution of 1688 : in the second it is proposed to include the

further documents from the State archives for the period from 1697 to

the final merging of the Brigade among the Dutch national troops, and

the departure If the British officers : and in the third, the Rotterdam

Papers, which form a separate series, will be printed.

The sources from which the papers contained in the

first Iwo volumes are drawn consist of several series of records

Preserved in the 'Rijks Archief at the Hague. They include extracts from

the Resolutions of the States-General, from the secret resolutions of

the same, from the ' Instruction Books,1 the files of the incoming

documents, and separate portfolios of requests, from the diplomatic

correspondence, the secret diplomatic correspondence, and the reports of

the ambassadors given to the States-General on their return to the

Hague. They also include extracts from the resolutions of the Council of

State, from the collection of letters sent to the Council of State, from

the commission books of the Land Council at the east side of the Meuse,

which preceded the Council of State (1581-84) and of the Council of

State, and from the portfolios marked Military Affairs. The names of the

officers are taken from the States of War, which are documents made up

with the object of showing the military establishment for the time

being, and the proportion in which its expenses fell to be defrayed by

the separate provinces which constituted the United Netherlands.

It will be noted that the

archives of the United Netherlands at the Hague do not furnish

illustrations of the earlier history of the Scottish troops, the reason

being that it was only after the Union of Utrecht, and the

reconciliation of the Walloon Provinces with the King of Spain, that the

permanent central government of the outstanding provinces took shape.

Previous to this the Scottish troops were either in the service of

Holland and Zealand alone, or in that of the States-General of the whole

associated provinces of the Low Countries during the campaigns against

Don John of Austria. As, however, special interest attaches to the early

services of the Scots in the war of independence, there are prefixed to

the papers which form the proper subject of the volume, a series of

extracts from the Resolutions and Pay Lists of Holland which supply the

blank. With this exception the mass of material has rendered it

necessary to confine the reproduction to the archives of the United

Netherlands. To search for and publish the whole documents relating to

the Brigade in the Low Countries would involve ransacking not only the

independent archives of Holland, but those also of Zealand, Guelderland,

and probably other provinces, and certainly those of the great garrison

towns like Breda, Bois-le-Duc, and Maestricht. But a considerable amount

of material has been obtained from the Records of Holland, which has

been found valuable for purposes of illustration and explanation, while

the annotation in regard to the personnel of the officers has been much

assisted by extracts from the Oath Books and Commission Books.

The extent of time

covered by the subject, and the clear-marked character of the periods

into which the history divides itself, indicated the method which has

been adopted in the arrangement of the materials. The papers have been

collected in sections corresponding to distinct historical developments,

and a short historical introduction, noting the services of the Scots

regiments, as far as they can be traced, prefixed to each section. The

documents have themselves been arranged, irrespective of the series of

Dutch records from which they come, in chronological order, subject,

however, to the collecting together, where this seemed advisable, of

those relating to a particular subject or the claims of a particular

individual.

THE SUCCESSION OF THE

REGIMENTS

The Scots Brigade in

Holland began by the enlistment of separate companies, each complete

under its own captain. At what time these were embodied into a distinct

regiment it is difficult to say, but they underwent the experience

afterwards undergone by the Black Watch, and by every administrative

battalion of rifle volunteers. Colonel Ormiston is referred to in 1573.

In 1586 the Scots companies were divided into two regiments under

Colonels Balfour and Patten, and by the time of the Spanish Armada, if

not indeed before, the elder regiment seems to have had its complete

regimental organisation. The second regiment was brought over complete

by Lord Buccleuch in 1603. The third was formed on a readjustment in

1628, and although from 1655 to 1660 the three were again converted into

two, and between 1665 and 1672 the third regiment became completely

Hollandised, and its place was taken, in 1673, by a newly raised one,

the two older regiments had an unbroken existence from 1588, if not from

1572, and from 1603 respectively, while the third, dating from 1673,

substantially represented the one formed in 1628.

But while from 1628

onwards there were substantially three permanent regiments in service,

on special occasions the number was increased. Thus in the campaign

against Don John of Austria, Stuarts regiment also served, and from the

allusion to other colonels, it would seem that there were others in the

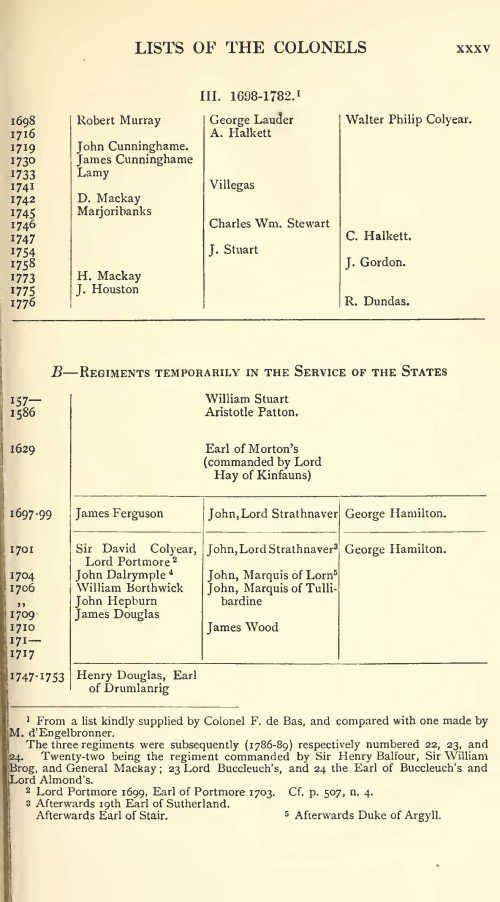

pay of other provinces. In 1629 the Earl of Morton's regiment, commanded

by Lord Hay of Kinfauns, served at the siege of Bois-le-Duc. In 1697-98

three additional Scottish regiments, Ferguson's, Lord Strathnaver, and

Hamilton's, were temporarily employed, replacing the English Brigade,

and again during the time of Marlborough three regiments (Lord

Portmore's, Lord Strathnaver, and Hamilton's) were employed, and reduced

after the Peace of Utrecht. Again a fourth regiment, commanded by the

Earl of Drumlanrig, was in service from 1747 to 1753.

CAVALRY, ETC.

The services of the Scots

were not confined to the infantry arm. During the earlier period there

seem to have been at least two companies (squadrons or troops) of

Scottish cavalry and sometimes more in the service of the States.

Captain Wishart received a commission as captain of horse-arquebusiers

in March 1586, and served until 1615 or 1616, when his company appears

to have been transferred to Sir William Balfour, who commanded it till

1628. William Edmond received a commission as captain of lancers in

1588, and led his squadron at least until his succession to the command

of the infantry regiment in 1699; and his son Thomas came from the

infantry to a cavalry command in 1625. Patrick Bruce was commissioned as

captain of a hundred lancers in 1593, and Thomas Erskine and Henry Bruce

appear as cavalry captains in 1599. Captain Hamilton, a gallant Scottish

cavalry captain, fell in the decisive charge at Nieuport in 1600. In

1604, after much deliberation and some remonstrance, the States accepted

the offer of Archibald Erskine to raise a company of cuirassiers; and

the troubles of a cavalry captain, the anxieties of the magistrates of

Zwolle in connection with his troop, and the questions that arose on his

death in 1608, will be found illustrated in the papers. In 1617 and 1620

Robert Irving and William Balfour appear as cavalry captains, the former

probably being succeeded by the younger Edmond, and at the close of the

Thirty Years' War, William Hay and Sir Robert Hume occupy a similar

position.

The papers also disclose

the names of artillerymen and engineers, while of the infantry officers

some, such as William Douglas and Henry Bruce, distinguished themselves

as inventors and scientific soldiers. John Cunningham won reputation as

an artillery officer at Haarlem, nor was he the only Scot who commanded

the artillery. On 30th June 1608, James Bruce's request to succeed Peter

Stuart was refused. Breda also requested that James Lawson, a Scot,

should be appointed cannoneer of the city. Samuel Prop, engineer,

appears in the States of War.

MILITARY ORGANISATION,

PAY, ETC.

The numbers of the

companies varied. Originally the ordinary strength appears to have been

one hundred and fifty for each ordinary company, and two hundred for the

colonel's (or life) company. Of the one hundred and fifty, one hundred

were musketeers (or harquebusiers) and fifty pikemen. In 1598 the

companies were temporarily reduced to one hundred and twenty heads. How

long the pikemen were continued is not certain, but General Mackay's

Memoirs show that 'old pikemen served in the Scottish campaign of

1689-90. (See documents showing establishment under William the Silent,

p. 43, Commissions, pp. 82-93.) The sergeant-major and the

provost-marshal appear in 1587, the ' minister' in 1597, and the

lieutenant-colonel and quartermaster in 1599. The establishment of a

company will be found detailed in the commissions printed on pp. 76-95.

It will be noted that in some cases one or two pipers are mentioned, and

in others none. In 1607 the colonels remonstrated against the English

and Scots companies being reduced to seventy rank and file, 'pesle-mesle

avec la reste de ramiee. In 1621 it was resolved to increase the foreign

companies to one hundred and twenty.

The number of companies

in a regiment seems to have varied, but in the reorganisation into three

regiments in 1628 it was fixed at ten companies. The difficulties that

attended the supply of men for the regiments, and the competition of

foreign states in the British recruiting field, are illustrated by a

series of documents relating to the recruiting in England and Scotland

between the years 1632 and 1638.

The rates of pay for the

different ranks in the time of William the Silent are shown by a

document from the archives of the Council of State, prefixed to the

States of War of 1579-1609.5 The commissions of 1586 and subsequent

years also show the agreed-on pay, and indicate a method of payment

which led to many questions. Thus for Colonel Balfour's company of two

hundred men, he was entitled to i?2200 of forty Flemish grotten (or

groats ?) per pound per month, each month being calculated as consisting

of thirty-two days, but the monthly payment was only made each

forty-eighth day, and the balance of one-third of the pay thus retained

constituted the arrears which led to so many claims on the part of the

Scottish officers, to the issue of letters of marque by the King of

Scotland in the case of Colonel Stuart, and to the compromises for slump

sums or annual pensions, in his, Sir William Murray's, Colonel

Balfour's, and other cases. In 1588 the objections of the Scottish

captains to this system, and their insistence on obtaining some security

for the settlement of their arrears, led to the dismissal of some of

them by the States-General, and to the others being required to sign a

declaration expressly stating their acquiescence in the practice. In

1596, however, the states of Holland improved the position somewhat by

paying the troops for which they were responsible every forty-second,

instead of every forty-eighth day.

When in 1678 the Brigade

had been fully established on its reorganised basis, the capitulation of

that year expressly stipulated, that the pay of the soldiers was to be

increased c d'un sous de plus par jour." In 1774 the men had 'twopence'

a week more pay than the Dutch troops. At that time a captain's pay came

to at most £140 sterling yearly, a colonel's was not above £350, and a

lieutenant's about £40, while that of the Swiss companies was much

higher.

The appointments of

subaltern officers seem originally to have been made by the captains,

who raised and brought over the companies. Later on they seem to have

been made by the Prince of Orange, who also filled any vacancy in the

higher ranks occurring in the field, commissions being subsequently

issued by the States-General confirming his appointment. In 1608 the

states of Holland resolved that the captains on their repartition should

not be allowed to fill vacancies in their lieutenancies and ensigncies

without the previous consent of the states or of the committee, who

reserved the right of appointment, and this right appears also to have

been exercised by other provincial states.

In 1588, after the

departure of the Earl of Leicester, the States revised and reformed

their whole military establishment, and instituted the system of

allocating regiments or companies to be directly paid and supported by

the different provinces, which is referred to when they are described as

'on the Repartition' of Holland, of Zealand, of Guelderland, or of any

other province. 'lis en firent, says Meteren, 'les repartissions sur

chasque province selon qu^lles estoyent quotisees et qu'elles

contribuoyent ens charges de la guerre, selon aussi que chasque Province

le pouvoit porter, ce que causa des bons et remarquables effets. Les

gens de guerre,*' he adds, 'pouvoyent asseurement scavoir en quelle

Province ils pouvoyent aller poursuiyvre leur payement, tellement que

s'il y avoit quelque faute en cela on le pouvoit incontinent scavoir et

le conseil d'Etat y pouvoit remedier. In addition to the ordinary

contributions of the provinces, extraordinary contributions were levied

on the more wealthy provinces, and the revenue derived from them was

administered by the Council of State. At the end of each year the

central authority settled accounts with the respective provinces, in

regard both to the ordinary and to the extraordinary contributions.

One result of this

somewhat complicated system was that the regiments were frequently

divided between two provinces, and indeed in 1655 the states of Holland

resolved, in view of the fact that of several regiments one portion

stood on their repartition and another on that of other provinces, to

bring all the forces on the Repartition of Holland together in complete

'Holland regiments; but it seems doubtful whether this was ever fully

carried out, although the two Scots regiments in 1655, and the three in

1662, are described as Holland regiments. Certainly in the latter part

of the century Mackay"s regiment was on the Repartition of Guelderland,

and in 1698 one regiment at least was on the repartition of more than

one province.

UNIFORM, A15MS, AND

EQUIPMENT

The appearance of the

Scottish soldiers in the early years of their service can be gathered

from occasional indications in the papers. In carrying the pike in the

Low Countries, they found themselves armed with a weapon similar to that

which in the hands of the Scottish spearmen had often repelled the

charges of England's chivalry. The Spaniards regarded the pike as la

seiiora y reyna de los armas, but at push of pike, they found their

match in the sturdy English infantry, and the ' sure men' of the Scots

Foot. The arquebuse gave place to the musket, and in 1689 one at least

of the regiments was in whole or in part fusiliejs.

In 1559, Prince Maurice

prescribed a uniform equipment for the troops in the service of the

States;x and the approved w.eapons seem to have been strictly insisted

on. Thus it is

I x 'Parmy l'Infanterie

ceux qui portoyent des Picques debvoyent avoir un Heaulme, un Gorgerin

avec la Angrasse devant et derriere, et une Espee. La picque devoit

estre longue de dix-huict pieds, et tout cela sur certaines peines

establies. II falloit pareillement que la

quatriesme partie de ceux qui portoyent des Picques fussent armes de

garde bas jusques au coulde, et au bas de larges tassettes. Les

Mousquetaires debvoyent avoir un Heaulme, une Espee, un Mousquet portant

une balle de dix en la Livre, et une Fourchelte. Les Harquebusiers

debvoyent avoir un Heaulme, une Espee, une bonne Harquebuse d'un calibre

qui debvoit porter une balle de vingt en la Livre, mais en tirant une

balle de 24 en la Livre, et chacun avoit ses gages et sa solde a

l'advenant. Nous avons trouve bon de dire cecy, afin que nos successeurs

puissent scavoir de quelles armes on s'est servy en ce temps en Pays-Bas

en ceste guerre' (Meteren, fol. 451, where the cavalry equipment is also

described. See also fol. 416. The fourth part of the pikemen were to be

picked and seasoned soldiers, of whom Mackay records that they stood by

and were cut down with his brother, their colonel, at Killiecrankie,

when the ' shot' men broke and fled noted that new levies were good men,

but ' armed after the fashion of their country.' It has been thought

that the Highland dress was worn by some at least of the Scots who

fought at Jteminant in 1578, and it would seem that at various periods a

considerable number of recruits were drawn from the Highlands. In 1576

an ' interpreter for the Scottish language was appointed in connection

with ' the affair and fault of certain Scotsmen,' and in 1747, the

orders had to be explained to some of the men of Lord Drumlanrig's

regiment in their own language, because they did not understand English.

Even in the days of Queen

Elizabeth, 'the red casaques' of the English soldiers had attracted

attention in the Low Countries. From at least the time of the

reorganisation in 1674, the Scots Brigade was clothed in the national

scarlet. In 1691, Mackay's regiment wore red, lined with red, and

Ramsay's red, lined with white. Lauder's being then in Scotland, the

colour of its facings has not been recorded, but from a picture of an

officer serving in it in the middle of the eighteenth century, it would

appear that then at least its facings were yellow. Curious evidence as

to the uniform of the Brigade in 1690 is preserved by a Highland

tradition. It is said that before Major Ferguson's expedition to the

Western Isles in 1690, the people of Egg were warned of its coming by a

man who had the gift of 'second-sight,' and that those who were taken

prisoners testified to the accuracy of his description, seeing the

troops, ' some being clad with red coats, some with white coats and

grenadier caps, some armed with sword and pike, and some with sword and

musket."' The author of Strictures on Military Discipline, comparing the

position of the Scots with that of the Swiss, observed, 'They enjoy no

privilege as British troops, except the trifling distinction of being

dressed in red, taking the right of the army when encamped or on a

march, and having twopence a week more pay for the private men than the

Dutch troops have.

'The question of rank,'

says the author of the ' Historical Account,' ' which in military

affairs is a serious matter, seems to have been decided between the

English and Scots by the antiquity of the regiments, perhaps rather by

the seniority of the colonels, but as royal troops, both always ranked

before the troops of the United Provinces or those belonging to German

princes, which right never was contested with regard to the Scots

Brigade until the year 1783.' Dr. Porteous the chaplain, in his ' Short

Account,' takes higher ground and says : ' Being royal troops, they

claimed, they demanded, and would not be refused the post of honour and

the precedence of all the troops in the service of the States. Even the

English regiments yielded it to the seniority of the Scots Brigade. This

station they occupied on every occasion for two hundred years, and in no

instance did they appear unworthy of it. They never lost a stand of

colours; even when whole battalions seemed to fall, the few that

remained gloried in preserving these emblems of their country.'

RELATIONS OF THE REGIMENTS

TO THE DUTCH GOVERNMENT AND THE BRITISH MONARCH

There were always

elements of difficulty and delicacy in an arrangement by which the

subjects of one state served in a body as soldiers of another. The

Netherlands looked to Austria, to France, and to England in succession

for a ruler whom they might substitute for the King of Spain. Queen

Elizabeth was too astute to accept the sovereignty; but through the

substantial aid she afforded, the impignoration to her of the cautionary

towns, and the appointment of her favourite as Governor-General and

Captain-General, she as nearly as possible in fact annexed the

Netherlands after the death of William the Silent. But the rule of the

Earl of Leicester, ineffective in the field, and productive of

heartburnings and jealousies in the council and the camp, rendered the

States very suspicious of further foreign interference. Thus when, in

1592, King James asserted his position as equivalent to that of his

haughty cousin of England—whose idiosyncrasies he is found palliating to

the representatives of the States, as weaknesses of her sex— by granting

a commission to Colonel Balfour to command all the Scots troops in the

Dutch service, the States refused to recognise it, and affirmed their

determination that none could serve in their lands on any other

commission than that of the States-General. In 1604 they again refused

to receive Lord Buccleuch as 'general of his nation' as recommended by

King James, although it was pressed as due to Scotland, and appropriate,

there having been a general of the English troops, and the Scots being

raised to an equal strength with the English. In 1653 the complete

conversion of the British troops into 'national Dutch' was canvassed,

and in 1665 it was carried out; but after the reorganisation under

William Henry of Orange, when the new English Brigade was formed, and

the old Scots was increased and resumed its own national character, the

combined British Brigade was definitely placed under the command of a

British officer, whose rank, pay, and precedence were clearly fixed by

the capitulation of January 1678, entered into by the Prince of Orange

as Captain-General and the Earl of Ossory. It was expressly stipulated

that the general should be a natural subject of the King of Great

Britain, and that, should his Majesty call the regiments to his service

at home, the States should allow them to be embarked at a port to be

selected. When, however, the critical occasion arrived and the king

sought to exercise the right of recall in 1688, the States refused to

let the regiments go, or to recognise the binding character of the

capitulation, founding with some special pleading on what appears to

have been a failure on the part of the Dutch government to fully carry

out its terms in reference to the increase of the pay. But the troops

were recognised in Britain as a part of the British army, and the

officers'' commissions subsisted in spite of a change from the one

establishment to the other. 'While, says the 'Historical Account,' 'the

British regiments were in the pay of Holland, the officers commissions

were in the name of the States, and it was not thought necessary they

should have other commissions, even when they were upon the

establishment of their own country, until vacancies happened, in which

case the new commissions were in the king's name. Thus when Colonel Hugh

Mackay came over to England on the recall of the Brigade in 1685, King

James promoted him to the rank of major-general, not considering him the

less as a colonel in his army that his former commission was in the name

of the States. And when the same General Mackay, who held his regiment

by a Dutch commission, was killed, the regiment was given a few days

after to Colonel AEneas Mackay, whose commission is English, and in the

name of King William and Queen Mary.

The officers of the

Brigade had to take an oath on receiving their commissions as captains

or in higher rank. In 1588, thev were also required to sign a

declaration stating their acquiescence in the system of pay. In 1653,

during the war with the English Commonwealth, a new form of oath was

devised, and again in 1664 in the war with Great Britain, when the

regiments were temporarily converted into ' national Dutch,' the

officers were required ' in addition to the usual military oath,' to

take one to the effect that they were under no obligation to obey, and

would not obey any commands except those of the States-General, and the

States their paymasters, or others indicated in the said oath of fealty,

and that they acknowledged none but the States as their sovereign

rulers. It is also noted that the new commissions then issued were in

Dutch.

Upon the reorganisation

of the Brigade under William Henry of Orange, and General Mackay, it was

placed on a more distinctive footing as British troops than ever before.

The British standing army was in its infancy, and the Scots and English

Brigades in Holland formed a very large proportion of its strength.

Their position in the Netherlands was analogous to that of Douglas's

(the Earl of Dumbarton's) regiment, now the Royal Scots, and of others

in the service of France. As Douglas's regiment became the 1st of the

Line, and two of the English-Dutch regiments that were formed in 1674

and came over in 1688, the 5th and 6th, so the three Scottish regiments,

had they remained in British pay after 1697, would have ranked very high

in the British army list.

It may indeed be

questioned whether the old regiment dating from the days of William the

Silent might not have claimed precedence even over the Royal Scots, on

the ground that while that regiment's descent is clear and continuous

from the union of a Scots regiment in France with the survivors of

Gustavus Adolphus's Scots troops, its earlier traditions, though august

and ancient, are more or less mythical. Certainly the old and the second

regiments would have been at least on an equal footing with the 3rd

Buffs—formerly the old English Holland regiment—while the third was

entitled to rank along with the fifth and sixth.

In the eighteenth century

the position of those serving in the Brigade as entitled to all the

privileges of British subjects was emphatically recognised. 'Even the

children,' says Dr. Porteous the chaplain, in his ' Short Account,' '

born in the Brigade were British subjects without naturalisation or any

other legal act. The men always swore the same oaths with other British

soldiers, and by an Act of Parliament, 27 Geo. u. the officers were

obliged as members of the British state serving under the Crown to take

the same oaths with officers serving in the British dominions. The

beating orders issued by the War Office were in the same terms with

those for other regiments : "' To serve His Majesty King George in the

regiment of foot commanded by--------------" accordingly all the men

were enlisted to serve His Majesty, not the States. Their colours, their

uniform, even the sash and the gorget were those of their country, and

the word of command was always given in the language of Scotland.

Such was their footing,

until in 1782 the States-General resolved, ' That after the first of

January 1783, these regiments shall be put on the same footing in every

respect with the national troops of Holland, and the officers are

required to take an oath of allegiance to the states of Holland and

renounce their allegiance to Great Britain for ever on or before the

above-mentioned day. Their colours, which are now British, are to be

taken from them and replaced with Dutch ones, and they are to wear the

uniform of the Provinces ; the word of command is to be given in Dutch ;

the officers are to wear orange sashes, and carry the same sort of

spontoons as the officers of other Dutch regiments.1 By the oath

prescribed for the officers they were bound to affirm that during their

service they would 'not acknowledge any one out of these Provinces as

their sovereign.1 This time there was no recovery for the Brigade.

Fifty-five of the officers refused to take the oath, resigned their

commissions in March 1783, and came over to Britain. They were placed on

half-pay without delay, and in 1793 His Majesty King George in. ' being

pleased to revive the Scots Brigade, a regiment of three battalions,

'the Scotch Brigade' of the British service, subsequently numbered as

the old 94th regiment of the line, was raised, to which they were

appointed.

RECURRENCE OF SAME NAMES

AMONG THE OFFICERS

In one respect the Scots

Brigade was peculiarly Scottish. Probably no military body ever existed

in which members of the same families were so constantly employed for

generations. 'The officers,' says Dr. Porteous, 'entered into the

service very early; they were trained up under their fathers and

grandfathers who had grown old in the service; they expected a slow,

certain, and unpurchased promotion, but almost always in the same corps,

and before they attained to command they were qualified for it. Though

they served a foreign state, yet not) in a distant country, they were

still under the eye of their own, and considered themselves as the

depositaries of her military fame. Hence their remarkable attachment to

one another, and to the country whose name they bore and from whence

they came; hence that high degree of ambition for supporting the renown

of Scotland and the glory of the Scots Brigade' The discipline of the

Brigade, enforced with far less severity than was customary in the

German and Swiss regiments in the same service, was acknowledged, and

the author of the 'Historical Account' observes that ' the rule observed

in the Brigade of giving commissions only to persons of those families

whom the more numerous class of the people in Scotland have from time

immemorial respected as their superiors, made it easy to maintain

authority without such severity.' The Scots officers also took care to

let the foreigners under whom they served know that the methods of

enforcing discipline in vogue in Continental armies would not do with

Scottish soldiery, for *Scotsmen would not easily be brought to bear

German punishments.'' 'Gentlemen of the families, says the writer of the

Strictures of Balfour Lord Burley, Scott Earl of Buccleuch, Preston of

Seton, Halkett of Pitfirran, and many of different families of the name

of Stewart, Hay, Sinclair, Douglas, Graham, Hamilton, etc., were among

the first who went over,' and a glance through the States of War shows

how repeatedly many of these names recurred in the Brigade throughout

its service. These lists indicate that the counties on the shores of the

Forth, and in particular Fife, had the closest connection with the

brigade, but Perthshire, Forfar, Aberdeenshire, and the Highlands, more

especially after General Mackay entered it, and other parts of Scotland

had their representatives under its colours. No name was more honourably

or more intimately associated with its fortunes than that of Balfour,

which in the first century of its existence supplied at least seventeen

or eighteen captains, among whom were Sir Henry Balfour and Barthold

Balfour, both colonels of the old regiment in the sixteenth century, Sir

David Balfour and Sir Philip Balfour (son of Colonel Barthold), both

colonels of the second and third regiments during part of the Thirty

Years' War, and another Barthold Balfour, who fell in command of the

second regiment at Killiecrankie. In the later years four Mackays,

Major-General Hugh of Scourie, killed at Stein-kirk; Brigadier-General

AEneas, his nephew, who died, as the .result of wounds received at

Namur; Colonel Donald killed at Fontenoy, son of the Brigadier; and

Colonel Hugh Mackay, held at different times the command of the same

regiment. The second regiment had three colonels of the name of Halkett,

and the third one. Two Hendersons, brothers, in succession commanded the

second regiment, and another, a generation later, the third. The names

of Erskine, Graham, and Murray occur twice, and those of Douglas,

Stewart, Scott, Colyear, and Cunningham thrice among the commanding;

officers. To enumerate the other members of these and other families,

such as Coutts, Livingstone, Sandilands, L'Amy, Lauder, who held

commissions, would be endless, but at one time the colonel,

lieutenant-colonel, and major of one regiment were all Kirkpatricks,

being probably a father and his two sons. Twice the colonel and

lieutenant-colonel of one regiment were both brothers of the name of

Mackay. That this family character was not confined to the old

regiments, but extended to those temporarily in service in 1697-98, is

shown by the fact that when Colonel Ferguson's regiment left the Dutch

service in 1699, there were five of his name among its officers, while

another was, in 1694, promoted a captain in Lauder's.

THE BRIGADE AS A MILITARY

SCHOOL

Scarcely less remarkable

was the Brigade as a training ground for officers who gained reputation

in after-life in the service of Great Britain and of foreign countries.

Some of the Dutch officers served in the civil wars; several of

Marlborough's major-generals and brigadiers came over as captains and

field-officers in 1688, and it is remarkable what a proportion of those

serving under the colours in that fateful year afterwards attained to

high commands.3 But the phenomenon was marked in later years. Writing in

1774 the author of the Strictures enumerates Colonel Cunningham of

Entricken, 'whose behaviour at Minorca and on other occasions did him

much honour,'' General James Murray, brother of Lord Elibank, Governor

of Quebec after the death of Wolfe, and known as Old Minorca, from his

gallant defence of that island, Sir William Stirling of Ardoch, General

Graham of the Venetian service, Colonel (then Lieutenant-General)

Graham, secretary to the Queen of Great Britain, Lieutenant-Colonel

Francis M'Lean, Lieutenant-General in the Portuguese service, Simon

Fraser, Lieutenant-Colonel of the 24th regiment and

Quarter-Master-General in Ireland, who fell as a General at Saratoga,

Thomas Stirling, Lieutenant-Colonel of the 42nd, the Honourable

Alexander Leslie, Lieutenant-Colonel of the 64th, James Bruce, David

Hepburn, the Honourable John Maitland, brother of the Earl of

Lauderdale, James Stewart, son-in-law of the Earl of Marchmont and

Lieutenant-Colonel of the 90th, Major Brown of the 70th, James Dundas of

Dundas, Sir Henry Seton, Bart., and Colonel Sir Robert Murray Keith. To

these should be added Robert Murray of Melgum, afterwards General Count

Murray in the Imperial service.

INCIDENTAL FEATURES OF THE

DOCUMENTS

The general character of

the service, and the conditions under which the Scots lived, fought, and

were paid in the Low Countries can only be gathered from a perusal of

the papers themselves. It has been shrewdly said that the Dutch were

more careful to record matters of money than feats of arms, and to the

actual services in the field the official papers contain only few direct

references. But here and there such references occur, and the date of a

widow^s petition, or a marked change in the personnel of a State of War,

dots the T's and strokes the t's of a dry allusion in an old folio to

some forgotten skirmish or the carnage of a great battle. The pension

lists, and the applications of widows (among whom those of Sir Robert

Henderson and Lieutenant-Colonel Allan Coutts were most importunate),

also illustrate how the Scottish officers intermarried with the people

among whom they lived, and occasionally with Italian and Spanish

gentlewomen and noble ladies of Brabant and Flanders. Specially

interesting also are the letters of the Scottish

sovereigns,—particularly that of King James on the battle of Nieuport in

1600,—and King Charles's solicitude for the ransom of the Scottish

prisoners taken at Calloo in 1638. The appointment by the States-General

of two of their number to attend the funeral of Lieutenant-Colonel

Henderson, ' with the short mantle,' in the same year, indicates

exceptional gallantry on the part of one of a family which had already

shed its blood and given its life for the cause of which Holland was the

guardian. Now and then a flash of humour enlivens the story of eager

spirits and niggard paymasters, as when 'to this suppliant the answer

must for the present be "Patience."' A pleasant feature is the

occasional recommendations by some of the provincial municipal

authorities of the Scottish captains stationed in their cities, and

although there are occasional complaints of the conduct of the

troops,—owing generally to the pay being in arrears,—and a warning by an

English commander, in 1615, as to the feeling getting up between a Scots

and a Dutch company, two of whose soldiers had had a fracas, the general

relations of the Scots with the Dutch population seem to have been

consistently friendly and cordial. Indeed, during the Twelve Years'

Truce one of the complaints of the inspecting officers was the extent to

which the soldiers left their garrisons to work for the country-people;

while another subject of animadversion was the occasional enlistment of

Dutchmen to fill vacancies in the companies. A frequent offence was the

passing off of outsiders to bring up the I numbers of the company, in

order to pass review at full strength on a sudden inspection, and one

unfortunate, Robert Stuart, was sentenced to be hung in 1602 for too

successfully thus passing off six sailors in the ranks of an infantry

company. The absence of officers in Scotland for too long a time is also

commented on, and the result of John de Witt's report on Captain

Gordon's company in 1609 was its being disbanded. A melancholy account

is given of the state of Erskine's cavalry squadron in 1606, and among

the papers is an apology for insubordination by some of Wishart's

troopers tendered to a court-martial. The proceedings of the

court-martial on Sergeant Geddie, charged with murder in 1619, are also

interesting; and the spirit of the old Scottish family feud is

illustrated by David Ramsay's energetic protest, in 1607, against the

slayer of his relative 'coming in his sight,'' as well as by Lord

Buccleuch's claim for justice in respect of the slaughter of Captain

Hamilton. The experiences of the surgeon are indicated by Dr.

Balcanqual's petition in 1618; and the regard of the troops for their

chaplain is shown by the Reverend Andrew Hunter's long service, his

receipt of an increase of pay in 1604, his Latin memorials of 1611 and

1618, and the interesting and honourable letter of the colonels in 1630,

in which they ask a further allowance for his widow, and state their

readiness 'to provide for our own minister. The divorce of Captain

Scott, the marriage of Caj>tain Lindsay with the released lady, and the

lawsuit of Captain Waddell with the Countess of Megen and the pupil-heir

of the great house of Croy, recalling as it does the happier experiences

of Quentin Durward, all find their way into the national archives. The

claims presented by Scottish officers on account of the arrears of their

pay, or of that due to relatives whom they represented, and the

deliberations of the States upon such claims constitute a very large

amount of the documents preserved. The main question appears to have

been to what extent the United Netherlands, as constituted by the Union

of Utrecht, were responsible for services rendered to the whole of the

Netherlands before the separation of the reconciled provinces. This is

the substantial question raised in Colonel Stuart's claims, and in those

of Sir William Balfour as the heir of his father, Sir Henry. It required

the issue of letters of marque, authorising Colonel Stuart to recoup

himself at the expense of Dutch shipping, to bring the States-General to

a serious consideration of his claims for services, which, whether

technically rendered to the 'nobles, Prelates, and burgesses sitting at

Antwerp,' to ' the nearer union,'' or to the States of Holland and

Zealand, were equally instrumental in securing the liberty and

independence of the Dutch Republic. His claims and those of Sir William

Balfour alike ended in a compromise; and the system of liquidating

liabilities and securing fidelity by a large balance of deferred pay was

fruitful of similar I claims and compromises with others, such as the

heir of Lord Buccleuch, who compounded his father's arrears, as to the

liability for which there had been no question, for a pension, the

promise of a regiment, and at least temporary freedom from the

maintenance of a near though unacknowledged relative, who ultimately

took her place among the Scott clan as 'Holland's Jean.' Among the

papers relating to Colonel ] Stuart's claims will be found two most

interesting reports by Dutch ambassadors of their visits to England and

Scotland, 9 containing passages delightfully illustrative of the

character of 'Queen Bess,' of the court and conduct of King James, and

of the general relations between the Protestant powers. One of

I the most valuable documents in a historical

sense, and most I interesting to the student of character and manners,

is the I graphic narrative of the Dutch

ambassadors who attended the baptism of King James's son, Prince Henry.

AUTHORITIES FOR HISTORY OF

THE BRIGADE

A word should be added as

to the special authorities for the History of the Brigade, which are

frequently referred to in this and the narratives prefixed to each

period into which the papers have been assorted. In 1774 there was

published 'Strictures on Military Discipline' in a series of letters,

with a Military Discourse: in which is interspersed some account of the

Scotch Brigade in the Dutch Service, by an Officer. This officer is said

to have been Colonel James Cunningham and the book advocates reforms in

the equipment and pay of the Brigade, the restoration of complete

recruiting in Scotland, and, indeed, the enlargement of the force and

the association with its infantry battalions of a proportion of the

other arms.

In 1794, this was

followed by 'An Historical Account of the British Regiments employed

since the Reign of Queen Elizabeth and King James'. in the Formation and

Defence of the Dutch Republic, particularly of the Scotch Brigade. It

was written just at the time when King George 'had been pleased to order

that these regiments should be embodied anew,1 and gives, in about a

hundred pages, a concise and fairly complete account of the services of

the Brigade. The information contained in the Dutch papers, however,

corrects it in some points, and the writer has fallen into the common

mistake of not observing that King William handed over six and not

merely three Scots regiments to the Dutch Government in 1697, and of

confounding the three old regiments with the three temporarily in the

Dutch service at that time and during the war of the Spanish Succession.

The error is a ,natural one, for when the Brigade returned at the Peace

of 'Ryswick Walter Philip Colyear commanded one of the old regiments,

while his brother Sir David Colyear, raised to the peerage as Lord

Portmore, was colonel of one of the additional ones, taken into service

in 1701.

In 1795 there was also

published ' An Exhortation to the Officers and Men of the First

Battalion of the Scotch Brigade. Delivered at the Castle of Edinburgh on

the 7th of June 1795, a few days before the battalion received their

colours, to which is added a Short Account of the Brigade by William

Porteous, | D.D., chaplain to the battalion. The author of the '

Historical Account' had compared the position of the officers of the

Brigade in Holland after the war with Great Britain began to that of

officers who had, in the execution of their duty and without any fault

or error on their part, fallen into the hands-of the enemy, and had

contended that ' whatever the means i may have been by which a British

regiment has fallen into the I enemy's hands, it cannot be in the power

of that enemy to extinguish or abolish it.' In addressing the

newly-formed battalion, the chaplain used words which indicate that its

embodiment was regarded in Great Britain not as the creation of a new

but as the resurrection of an old regiment. ' Our ears,' said Dr.

Porteous, i have been accustomed to hear of the fame of the Scotch

Brigade; of the moderation, sobriety, and honesty, as well as of the

courage and patience of this corps; you have not to erect a new fabric,

but to build on the reputation of your predecessors, and I am confident

you will not disgrace them.' His 'Short' Account, while covering much

the same ground as the 'Historical Account, contains some additional

particulars. There is also a short notice of the Brigade appended to

Grose's Military Antiquities, and a note upon it in Steven's History of

the Scotch Church at Rotterdam.

Among the papers of Mrs.

Stopford Sackville, at Drayton House, Nottinghamshire, is a copy of a

document (after 1772), ' Facts relative to the Scotch Brigade in the

Service of Holland.'

There are of course

allusions to the services of the Scots in j the many English, Dutch,

French, Spanish, and Italian histories of the War of Independence. For

the time of Prince Maurice, the best authority is Orler's Lauriers de

Nassau, and for that j of his brother the Memoires de Frederick Henry

Prince d'Orange. For the campaigns of William Henry, the Memoirs of

Bernardi and of Carleton, the Life of William III., and the History of

Holland supply a limited amount of information.

The Editor has to record his sense of the assistance

he has received from Dr. Mendels and M. d'Engelbronner who transcribed

the documents at the Hague, and whose intelligent researches have

greatly aided the work of annotation, and particularly from Colonel de

Bas, the keeper of the Archives of the Royal House of Orange at the

Hague, who supplied valuable information as to the succession of the

regiments in the eighteenth century; and also to express his grateful

thanks to many friends and correspondents in Scotland and elsewhere, too

numerous to enumerate, who, by supplying particulars as to their

ancestors who served in the Brigade, or otherwise, have enabled him in

many cases to identify the individuals whose names appear in the States

of War. Similar acknowledgments are due to Mr. J. Rudolff Hugo, and to

the Rev. J. Ballingall, Rhynd, Perthshire, who have undertaken the

labours of carrying out and revising the translation of the Dutch

documents.

It had originally been intended to print the Dutch

text as well as the English translation of the Dutch documents, but the

volume of material was so great that on careful consideration the

Council were satisfied that they must confine themselves to printing the

English translation of Dutch originals, and the French text alone of

documents in French. For the convenience of scholars the complete

transcripts of the original Dutch here translated, and of other

documents, including the lists from the Commission and Oath Books, which

the Editor has used in the preparation and annotation of these volumes,

will be deposited and preserved in the Advocates1 Library, Edinburgh.

J. F.

Kinmundy, Aberdeenshire,

11th Novr. 1898.

Having now given

you the introduction you can read