|

The Welcome Home—The Crisis

in the Free Church of Scotland—A Visit to Lovedale—His Home-going—The

Funeral—James Stewart and Cecil Rhodes—The Meeting of Native Delegates at

the Grave—The Native College— The Fulfilment of the Dream of his Youth.

‘Let the night come before we praise

the day. ‘—Old Proverb.

‘Waiting as a soldier on parade, in

preparation for prompt obedience, feeling no desire to go, but ready.

‘—Lord Salisbury on

Gladstone.

So little done, so much to

do.’—Rhodes’s death-bed Commentary

on his Career.

Moriamur in

simplicitate nostra’

(Let us die in our simplicity).—The

Motto of the Maccabees.

AFTER

his moderatorship, Stewart returned to

Lovedale in 1899, and came back to Scotland in 1900. In May of that year

he presided at the opening of the General Assembly. After another visit to

Lovedale in 1901, he returned to Edinburgh in 1902, to deliver the Duff

lectures on missions, which were published in 1903,

under the title of Dawn in

the Dark Continent.

In

1903

he made a second visit to America, that he might examine all the new

methods in its Negro Colleges.

He had previously been examined by

two physicians in Edinburgh, who reported that his heart had been weakened

by overstrain, and urged him to give up all work except the general

superintendence of the mission. But ‘the natural and becoming indolence of

age’ had no attractions for him. To him the want of occupation was not

rest. In this he was like Livingstone, who tells us in his Last

Journals that he was always ill when idle. With failing strength but

never-failing will, he kept to his post.

Returning to Lovedale in April

1904,

he received a right royal welcome from the staff, the

pupils, and the apprentices, who lined the long avenue leading to his

house. ‘He had come back to stay,’ he said— this from the Christian

Express. ‘He seemed bright and well, his voice clear and strong, as he

stood up to address all those who gathered to welcome him back again to

his own kingdom. To the students his message was the same unchanging

theme—Righteousness and hard work would lift them up as a race, and

nothing else would.’

‘His first act on returning was

eminently characteristic of the man. Hearing that a Presbytery meeting was

being held that very afternoon at Macfarlan, within a couple of hours of

his arrival in Lovedale, he was driving as fast as good horses would take

him, along the Tyumie road. And so, at first sight, it seemed as if Dr.

Stewart had returned in the fulness of vigour and strength. After a time

it was evident that this was not so. The old fires still burned clear and

bright, lighting up his eyes with their glow and warmth; but the figure

was a little more bent, the step a little slower, his manner more gentle.

Now and again he was seen to rest by the wayside; he had even been found

sitting on a mound by one who told the tale. In Africa it is not a

wonderful sight to find one sitting waiting, but it was passing strange

for the ever active head of Lovedale to rest on any errand of his. And men

knew that his threescore years and ten, with all their fulness of service,

and wealth of devotion to duty, had not left him untouched in their

passing.’

In July 1904 the First General

Missionary Conference in Africa was held at Johannesburg. All the

Protestant missions were represented. Dr. Stewart was unanimously chosen

President, and conducted the meetings to the entire satisfaction of all

the members. He had then several interviews with Lord Milner, and obtained

his support for the cause of the Higher Education of the Natives.

In November 1904 he gave his

evidence before the Native Affairs Commission in Cape Town. His mind then

seemed as active as ever, and he displayed very great ability in setting

forth his plans, and meeting all sorts of objections.

He also then interviewed the

Governor and the other ministers of State about the decision of the House

of Lords in the Scottish Church Case. He then received their promise that

they would not allow Lovedale to pass into the possession of the minority.

The final decision in such a case lay with the Cape Government. The

Governor communicated his decision to the Home Government.

In January 1905 he was again in Cape

Town in the interests of Education and the natives. That was his last

journey from home. His friends believed that it greatly weakened him. It

was then less than a year before his death, and the effort was a

remarkable triumph of the soul over the body.

It must be sorrowfully recorded that

his last years were darkened by three very sore disappointments -

Ethiopianism, the Mzimba Case, and the Church Crisis in Scotland. The

first and second of these trials have been described in Chapter xxvii.

Mzimba was one of the most promising, trusted, and favoured of the

Lovedale pupils. His secession and the accompanying circumstances gave

Stewart a keen sense of bereavement.

Wave pressed upon wave and the

billows went over his soul. Before the Mzimba trouble had passed away, a

fresh catastrophe faced him. The decision of the House of Lords in the

case of the Free Church versus the United Free Church of Scotland

fell upon Lovedale as a bolt out of the blue. [In May 1905 I addressed a

native congregation not far from Lovedale. At the close a stalwart Kafir

came striding up and asked me through the interpreter what I thought of

the Twenty-four. That was their name for the small minority in the General

Assembly who had voted against union. The native newspapers were then

rousing into activity the latent sympathies with Ethiopianism and all

other forces of insubordination, and fostering the hope that the natives

might gain possession of the properties and endowments at Lovedale and

elsewhere.] The Legal Free Church claimed everything belonging to Lovedale.

The surprising events in the Home Church created anxiety about the future

of the mission. A large sum had been collected for extensions, but an

arresting hand was at once laid upon all the cherished plans. Stewart had

to contemplate the possibility of the Legal Free Church appropriating all

the fruits of forty years’ unceasing efforts, though they had not one

missionary, and could not possibly carry on the mission. A friend writes:

‘The burden of this last sorrow hastened the end. Though he lived to have

the burden lightened, and to feel assured that the worst he anticipated

could not happen, Dr. Stewart’s splendid physique had been overstrained,

and signs of heart-failure began to appear.’

In 1905 I spent three days with him

at Lovedale, six months before his last call came to him. [I was soon

reminded of the extent of Lovedale. Towards evening I said to Mrs.

Stewart, ‘I will take a walk round the buildings and grounds.’ ‘You cannot

do that before dark,’ she replied, ‘but I will get the horses inspanned

and drive you round.’ ] Dr. Stewart had then in his body the ‘secret

token’ that the King was about to send for him. He knew that he must die

soon and that he might die any day. If it were the will of God, he would

have wished five years more, that he might set in order the things that

were wanting at Lovedale, and see the Native College established. About

this scheme he was hopeful, as several of the leaders in that movement had

privately intimated their intentions and wishes, but nothing must be said

about it in the meantime. For the sake of the natives he hoped that every

department of his work might be preserved. His spirit was saintly and

chastened, and he bore himself patiently and bravely. The bitter

experiences in recent years had left in him no trace of bitterness, but

his strenuous life had deepened the thought-lines on his strong face, and

his frame had lost a little of its palm-like uprightness. His convictions

about disputed matters were as strong as ever, but he did not say a hard

word against anybody. Student days and many of his experiences were very

genially recalled, but no word that could suggest self-praise escaped his

lips.

Like John Knox, be could ‘interlace

merriness with earnest matters,’ for he believed in heart-easing mirth.

[He mentioned that a few weeks ago there had been a fire in one of the

buildings, and he had rushed out to help in extinguishing it. ‘This did me

harm,’ he said, ‘but I had a "nicht wi’ Burns"—a Scottish phrase for an

evening’s entertainment with the songs of Burns. Fun with him was the

holiday of the mind, and practically the only holiday he ever took since

his student days. He could laugh tears.] Often the fine smile of his

youthful days lighted up his face.

Though he had to keep in bed till

noon, several hours daily were spent in the office. Appeals from family

and friends could not avail: it was best, he said, that he should keep at

his post to the end. Though then always weary in the work, he was never

weary of it. He believed that the labour we delight in physics pain, and

his body, as a well-trained slave, had learned to obey at once the behests

of the masterful will. But the bow so long unslackened had almost lost its

spring.

He took a very humble view of his

work, but said emphatically that if he had life to begin over again, he

would not wish to spend his energies in another way or sphere. His tones

as well as his words showed how deeply he was touched by the pathos of

parting. The consolations of Jesus Christ were equal to all his needs.

Heedless of my many protests, he

must gather together all his staff in the evening, preside, and give words

of welcome to his fellow-student. His was the fine, self-sacrificing,

old-world courtesy of the Highland chieftain, who must rise from his

death-bed to show hospitality to his guest. He must stand up and speak,

although he had to lean hard on the back of his chair, while his pale face

and quick breathing revealed the great effort he was making. The occasion

had all the sacredness which belongs to last things. It was his last

address to a company.

After that evening, he left his

bedroom only twice, but he did not leave off his work till within a

fortnight of his home-going, when his hand refused to hold the pen.

His taper burnt clear to the close.

Surrounded by his wife and children, he departed this life on the evening

of December 21, 1905, in his seventy-fifth year. Then was fulfilled

his favourite text—’ It shall come to pass, that at evening time it shall

be light.’

The funeral was on Christmas Day.

All races and denominations in South Africa were represented in the

throng. The text was from 2 Samuel iii. 38, ‘Know ye not there is a

prince and a great man fallen this day in Israel?’

A vast procession of men and women

on foot, with a long line of vehicles and horsemen following the bier,

wended their way through the valley of the Tyumie, and up the slopes of

Sandili’s Kop, a rocky height about a mile and a half east of Lovedale,

and facing the College. The far-extending buildings of Lovedale are

visible from the grave. The South African Scot thus describes the

burial: ‘The scene at Sandili’s Kop on Christmas Day was a fitting close

to the career of a great leader and missionary. The grave was carved out

of solid rock, and can be seen from any point of the valley where Lovedale

is situated. Round the grave were gathered representatives of the United

Free Church of Scotland, the South African Presbyterian Church, the Dutch

Reformed Church, the Church of England, the Wesleyan, the Congregational,

and the Baptist Churches. Though a Presbyterian by training and

Conviction, Dr. Stewart belonged to the Church Catholic, and all the

Churches claimed him as their own. The great gathering of black and white,

many different races and nationalities, stood in serried ranks around the

Kop. The Rev. J. Lennox, his senior missionary assistant, spoke briefly

and eloquently of his magnificent powers of mind and heart, and of his

complete devotion to the well-being of the natives of South Africa. The

hymn, "O Love that wilt not let me go," was sung. Then a Kafir hymn and a

prayer in Kafir, in which it was said that God had "dried up the fountain

from which they were accustomed to drink." When the grave was closed, it

was covered with flowers sent by representative men and women from all

parts of South Africa. With a feeling of deep sadness that the earthly

career of a great and good man had closed, and with a deep assurance that

the life he lived will tell on the history of the country for generations,

the crowd slowly dispersed.’

At the close of the service, they

sang a hymn which Dr. Stewart often used—’ Holy, holy, holy, Lord God

Almighty.’ It was thus that devout men carried him to his grave and made

great lamentation over him. The only inscription on the grave is ‘James

Stewart, Missionary.’

There is a close parallel between

the burial of James Stewart and that of Cecil Rhodes. Both the tombs are

on a hill-top, both were blasted out of the solid rock, and both are near

the scene of great achievements. We find the explanation of this

similarity, not in the notion of imitation, but in the fact that these

men, or their friends, were in similar circumstances and swayed by similar

motives. [Dr. Stewart expressed no wish whatever about his grave.

Sandili’s Kop was chosen by Mrs. Stewart with the approbation of the

Lovedale staff. Some suggested the Matoppo where Rhodes was buried, and

which he had set apart as a South African Waihalla, or open-air

Westminster Abbey, the resting-place of those who had served their country

nobly. Rhodes had a high appreciation of Stewart’s aims. In his interview

with General Booth, he said: ‘Ah, General, you are right, you have the

better of me after all. I am trying to make new countries, you are making

new men.’ ‘That is my dream—all English,’ said Rhodes, sweeping with his

hand the map from the Cape to the Zambesi.] The traveller at Rhodes’s

grave, amid the fantastic castled crags of the Matoppo Hills, looks down

on the site of the historic meeting of Rhodes with the Matabele Indunas.

With supreme bravery he there took his life in his hand, went unarmed and

unescorted into the stronghold of his enemies, and brought to a close the

second Matabele war. As he returned he said that the scene of that day was

‘one of those things that make life worth living.’ It was natural that he

should desire to be buried near that spot. Lovedale was to James Stewart

at least all that the Matoppo Hills were to Cecil Rhodes. Both were great

dreamers and realisers of dreams, though with different ideals both

devoted their lives to the land of their adoption; both gratified the

natives by choosing a grave among them; both were far-seeing, imaginative,

and self-sacrificing imperialists who had a warm mutual regard; both were

mourned by natives and whites alike; and it is fitting that the dust of

each should repose near the scene of his noblest actions. The visitor at

either grave may remember the words, ‘If you wish a monument, look

around.’ Surveying Lovedale from Sandili’s Kop, the visitor may say, ‘That

is Dr. Stewart’s monument.’ His noblest monument is in the hearts and

careers of those to whom he devoted all his powers.

A coloured ex-pupil of Lovedale

wrote: ‘It seems to me that the Doctor has honoured us coloured people by

choosing that spot in the veldt for his last resting-place, not among the

high and honoured, but far away, as if to have his rest more perfect, and

make his grave free for us all to visit.’

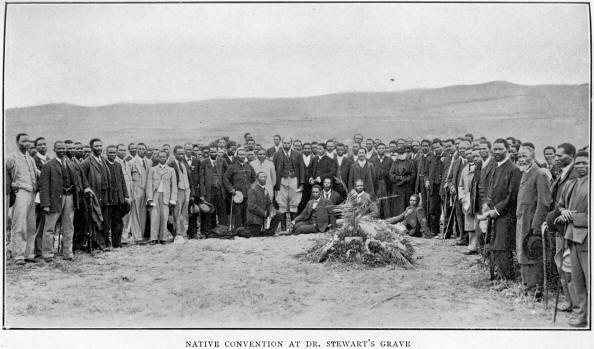

On the 28th of December, exactly a

week after his death, one hundred and thirty-two delegates,

representatives of one hundred and fifty thousand natives, who owe all

they are to missionaries, held a memorial service at Dr. Stewart’s grave,

in connection with the ‘Lovedale Native Convention.' [On his death-bed

Stewart had made all the arrangements for the comfort of the delegates.]

They had come together to consider the establishment of an Inter-State

Colonial College for the higher education of the natives of South Africa.

Lovedale was the right trysting-place for them, for its success had

inspired the idea of a native central college. They unanimously resolved

to urge the States to establish such a college, and to establish it at

Lovedale, and they agreed to raise a sum of money for its support. [It has

since been stated that the natives are likely to raise $50,000 for this

object. When he began in 1866, the Christian education of the natives was

considered by many an enterprise of a dangerous and Utopian character.] To

live thus in the hearts of men is not to die. One of the resolutions

adopted at the Native Conference was: ‘That your petitioners further

desire to express their strong conviction that it is essential to the

success of the proposed college that these missions, to whose efforts in

the past the natives owe all the education they are now receiving, should

be represented on the governing body of the college.’ This was a

remarkable climax to a remarkable career.

‘When the biography of your late

husband is written,’ writes Mr. E. B. Sargant, Resident Commissioner of

Basutoland, ‘no one who reads it can fail to be struck with the wonderful

manner in which his work began, as it were, a new life, with the meeting

of that Convention, a few days after his death.’

The grand vision of his youth and of

his whole life had not been a mocking mirage. For he was not permitted to

see death till he had almost seen the realisation of his boldest dreams.

He was thus felix opportunitate mortis, favoured in the moment and

manner of death. Very rarely in history has any ‘great pioneer had such a

remarkable success. Like the runner in classic story, he had fallen, but

fallen with his outstretched hand on the goal. [His dreams were very bold,

for he had hoped that even Livingstonia would be in alliance with the

Native College.]

So far as the visible part of his

life is concerned, we have no need to raise over his grave the pagan

symbol of a broken, uncompleted pillar. The fitting monument for him is a

column carried up to its full height and crowned with its capital.

Enlarger of the Kingdom (Melirer

des Reiches) is a title of the highest honour, which the Germans give

only to a very few of their greatest warriors and statesmen. It can be

given to ‘James Stewart, Missionary.’ |