|

His quenchless

Hope—Steadfast Faith—Missionary Promises—A needful Sphere—The Power of

Contrast—Inspiration from Church History—Visible Fruits.

‘Thus with somewhat of the

seer

Must the moral pioneer

From the future borrow;

Clothe the waste with dreams of grain,

And on midnight’s sky of rain

Paint the golden morrow.’

— Whillier

The Bible, from first to last, is

one unbroken, persistent call to hope. —Dean

Church.

‘We are saved by hope.’—The

Aposile Paul.

FOREIGN missionaries have the most

discouraging spheres in the world, and are usually the most hopeful of

men. Stewart was in this respect a good representative of his class, for

his hopefulness was subjected to the severest tests, and yet he did not

hang his harp on the willows. His was the secret of annexing the future to

the present and the harvest to the seed-time, and he saw in ridiculously

mean beginnings the prophecy of great things. His optimism is revealed in

every book he wrote and in every one of his missionary addresses. In his

Love-dale he writes: ‘The great future of the missionary enterprise

may be left to take care of itself. It is safe in the hands of its

Founder. Its progress means the gradual spread of Christianity. Its final

success means that the future religion of mankind will be the religion of

Jesus Christ, and the future civilisation of the world a Christian

civilisation, whatever its form may be.

. . .

And that is just what we labour for—a day in the future

when the Dark Continent shall be a continent of light and progress, of

cities and civilisation and Christianity. There is no good reason to doubt

the coming of such a day.’

He never lost his faith in Africa’s

redemption. In his Moderator’s address he said, ‘All question as to the

final success of the work may be set at rest.’

‘In the greatest books on missions

there is not,’ he tells us, ‘the sound of a single depressing note.’

‘Don’t let despair begin with you,’ said one of his colleagues, ‘let it

begin with us.’ Great hopes make great men and missionaries.

What are the sources of this

quenchless hope? It is rooted in an unwavering Christian faith. In

ordinary circumstances only a whole-hearted faith can induce a thoughtful

man to face the enormous difficulties of the field. He who hopes to

overthrow heathen systems must be very sure that his feet are planted upon

the eternal rock. An invincible belief in the recoverableness of the

heathen is the foundation of all missions. The missionary’s faith is

increased by his sacrificing

worldly ambitions and devoting himself to a life of exile. Such a man has

no prospect of making a fortune and enjoying years of rest at home. The

work before him is fitted to shatter the hope that is sentimental, and the

faith that has not been confirmed. The difficulties that confront him call

out all his spiritual reserves. Consciousness of purity of motive brings

him into the right mood and

attitude for great inspirations. The missionary at his best has the spirit

of Arbousset, one of the earliest French missionaries to the Basutos. When

he landed at Cape Town and gazed at the Table Mount, the gigantic barrier

of rock became to him a symbol of the heathenism he hoped to overthrow.

‘Who art thou, O great mountain?’ he asked. ‘Before Zerubbabel, thou shalt

become a plain.’

The missionary broods more than

others over the missionary promises, and these are the most

astonishing and inspiring utterances in the whole world. Use and wont has

blunted the edge of our wonder, and only by an effort can we dismiss our

dull associations and grasp the unfailing optimism of the Bible. The

greatest literary miracle in the world is the unity of the Bible, and its

hope of the conversion of all nations. Its writers belonged to one of the

smallest and most exclusive races in the world; its books were written at

different times, by very different men, and amid various tendencies, and

yet they all introduce us to a King who is to establish a world-wide and

world-long kingdom. As Abraham was sitting under the great oak at Mamre,

he was told that he would have a chosen son, that his son would be the

father of a chosen nation, and that the nation would have a chosen seed in

whom all the families of the earth should be blessed. The hope of the

conversion of the whole world lives in the heart of the whole Bible. The

strongest utterances of this invincible optimism came from the prophets

when their land was in ruins and their religious institutions were caught

in the rapids and hurrying on to destruction. The same spirit pervades the

New Testament; for it was written by fervent missionaries—apostle is the

Greek word for a missionary—and is everywhere full of the missionary

spirit. Its great oft-recurring words are outgoing—teach, call, keep,

heal, say, go, etc. The beloved disciple, even when a prisoner in Patmos,

and in a day when heathenism was triumphant everywhere, wrote as if he

already heard the tread of the coming millions of Gentile converts

hurrying on to the mystic Zion, the seat of Him who is ‘the Desire of all

nations.’ He saw his Divine Master in vision as a Roman warrior—a

bowman—going forth conquering and to conquer and crowned with victory. The

missionary lives in the spiritual ozone of such truths, and thus his hopes

are fostered. Stewart, by pitching the tent of his meditation among the

promises, breathed that spirit of victory which throbs at the heart of

both the Testaments. With him the Christ that is to be is Christ the

Conqueror. One of them had the power of a charm over him—’ Ethiopia shall

haste to stretch out her hands unto God.’ He hoped to mould the poetry of

the Christian life out of the hard, dull prose of paganism.

The foreign missionary has usually

one notable advantage over the average pastor or Christian worker at home:

he feels that he is where he is greatly needed. His work is not

tame and commonplace, and he has all the inspiration that comes from a

vast sphere and a very great and fresh enterprise. He is preaching the

glad tidings to those who, but for him, would probably never hear it, and

by his very presence he is doing something to lessen the surrounding

darkness. The spirit of enterprise was very strong in Stewart, and,

sanctified by grace, it made him a prince of missionaries.

There can be no doubt that he gained

not a little additional inspiration from the hundreds of young people

under his influence. The very flower of South Africa came to Lovedale, and

they represented the most vigorous and prolific races in the world to-day.

Very different were they from the decaying race for whom John Eliot

compiled a grammar and translated the Bible. Not a member of that tribe

now lives. The fact that the pupils at Lovedale belonged to various

tribes, stimulated emulation among them, and purified and guided their

racial jealousies. The Principal touched their lives at every point, and

through them he influenced nearly all the tribes in the land. They offered

him the very opportunity for which he had passionately yearned. In his

hands was the making of those chosen youths who were to be the makers of

the new South Africa. Lovedale thus had for him such a charm as a great

university has for its leading professors. It was a power-house, a

generating and distributing station whence new forces were to be conveyed

over the land. He thought that the Gospel was more likely to spread in

Africa from the south than from the north. One of his dreams was about a

chain of Lovedales stretching to Khartoum and beyond. He asked Rhodes to

give him a site in Rhodesia for one of them. He thought imperially.

Contrast

wonderfully helps the missionary to preserve his apostolic optimism. He

has the best opportunities in the world for the study of comparative

religion, for everyday religions and the religion are at work

before his eyes. The merely intellectual study of this great subject is

fitted to make a profound impression. Max Muller says that ‘he who knows

only one religion, knows none.’ This exaggeration suggests a great truth.

He elsewhere says more truly, ‘No one who has not examined patiently and

honestly the other religions of the world can know what Christianity

really is, or can join with such truth and sincerity in the words of St.

Paul: I am not ashamed of the Gospel of Christ!’ Only by setting Christ’s

religion by the side of one of its rivals can we gain the fullest

persuasion of the peerless excellences of the Christian faith. But the

study of heathen religions in books is often very misleading. We should

generously appreciate the elements of good in them, but we want to know

how they work. Many recently believed that the Bhuddism of Tibet contained

wonderful treasures of religious knowledge, and they hoped to find a new

Messias there. Those who have recently lifted the veil tell us that

Tibetan Bhuddism is rude idolatry and mere devil-worship. [A young Indian

physician witnessed for the first time the celebration of the Lord’s

Supper in Scotland. He wept throughout the service. When asked the reason,

he said: ‘I tried to understand all that was said and done: I thought of

the beauty of your religion, of its love to man, its pity for the sinful

and the sorrowful. I then thought of my India, and of the many sad things

in our religion. I thought of its cruelty to our widows. When I put the

two religions alongside of each other I could do nothing but weep.’

]

There can scarcely be a more

miserable religion under heaven than the African, and the missionary who

daily witnesses it is likely to appreciate the blessedness of the

Christian faith more than the average Christian at home usually does. We

have here one of the liberalising influences of the missionary’s

enthusiasm. He is not tempted to mistake his own horizon for the earth’s.

Church history

rightly studied breaks the spell of despondency. His

Journal shows that Stewart, when exploring in the heart of Africa, had a

peculiar fondness for the Acts of the Apostles as a record of missionary

enterprise, and that he brooded over it

with an eye to his own career,

saying to himself the while—’I also am a missionary.’ The Foreign

Missionary has every day an experience remarkably like that of the

leaders in the New Testament churches. He is therefore in the best

possible position for understanding, and receiving constant inspiration

from, the photos of church-life in the Epistles and the Acts of the

Apostles. How wonderful the story when one brings to it a realising

historical imagination. Paul and Silas crossed over to Europe as

travelling artisans. But they went as Heralds of Jesus Christ, and in the

spirit of conquerors. They hoped to rescue from heathendom cultured Rome

and the untutored nations, and they have done it. What moral and spiritual

miracles the pair accomplished To-day there is not a man, woman, or child

on the face of the earth who worships the gods that then had sway over all

Europe. It is true that Christ’s kingdom came not then with observation.

As Stewart points out more than once, the Roman historians, famed as they

were for their eagle-eyed acuteness, have, during the first three

centuries, only some ten or twelve brief and scornful references to the

Church of Christ. Yet ere long ‘the Empires fell one upon another to form

a pedestal upon which to build the Church.’ Stewart’s writings show that

he had made himself familiar with the triumphant march of the Church

through the ages, and thus he had the hope, we should rather say the

expectation, that the experience of the early Churches would be repeated

in Africa. ‘When one has seen the Catacombs,’ a visitor to Rome says, ‘one

understands the great explosion of Christianity under Constantine, the

city had been conquered underground.’ Stewart believed that something like

that was taking place around him. While surrounded by the night, he was

confident of the dawn, and the dawn overtook him.

For the facts he had

witnessed justified to a large extent his lifelong optimism. The previous

chapters record some of these facts. He believed that a great missionary

epoch had already begun, and that it would have immense issues. ‘Young

missionaries may despair,’ said a veteran Indian missionary; ‘we who have

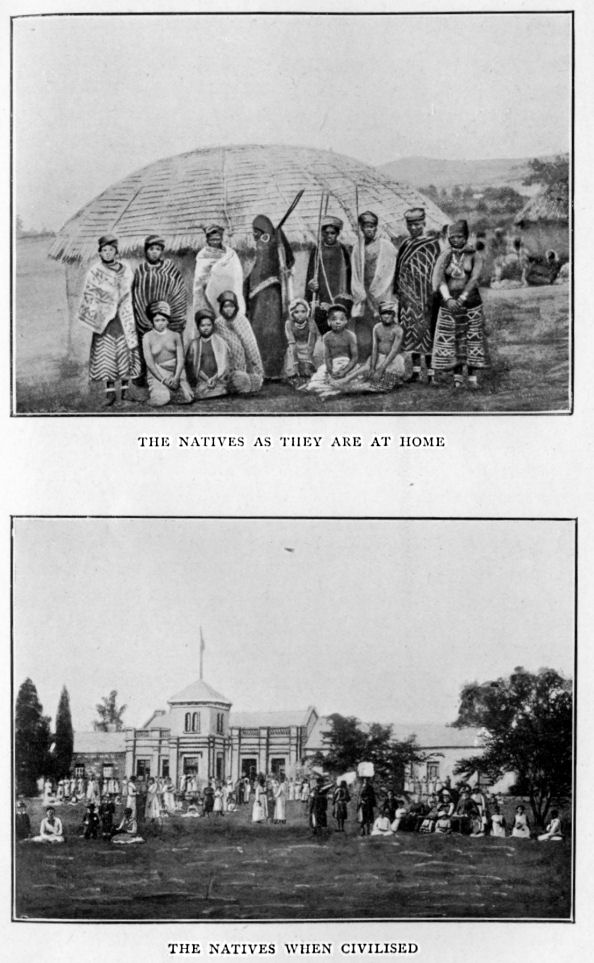

witnessed such stupendous changes never can.’ Before the Native Affairs

Commission Stewart made a similar statement about the improvements he had

witnessed, especially in the native women, whose appearance had been

entirely changed. The sight of the boys and girls at Lovedale was fitted

to break the spell of despondency if it had ever mastered him.

In his Dawn he says:—‘A fair

and just, and yet not optimistic, survey of the missionary situation of

to-day would lead us to the belief that it is better, more encouraging,

and more full of real results than at any time since the days of the

Apostles. How poorly at the best have we discharged the great duties God

has laid upon us in virtue of the gifts He has bestowed! Still, in God’s

time, apparently a better day is coming, for clearly "o’er that weird

continent morn is slowly breaking." We return again in a final word to the

one power and influence sufficient for the regeneration of Africa. It has

been the keynote through all these pages. That one force is the religion

of Jesus Christ, taught not merely by the white man’s words, but what is

far better, by his life, as showing the true spirit of that religion.’

Believing thus that the best is yet to be, the shadows of the morning were

tinged in his eyes with the glory of the approaching dawn.

Shortly before his death Coillard

wrote—March 4, 1904—’Read Dr. Stewart’s Dawn in the Dark Continent,

Daybreak in Livingstonia, and Among the Wild Ngoni, by Dr.

Elmslie. To state my impressions would be impossible. I am humbled and

moved to wonder. What great things the Lord has done there.’

‘We are saved by hope,’ the Apostle

says. The expectation of victory is often the guarantee of victory, for

every great battle is lost or won in the soul. In our Navy the signal for

a close engagement is the same as the signal for a victory. To hope is

often to achieve. These are the reasons why Stewart hoped all things not

impossible, and believed all things not unreasonable, and preserved his

unclouded optimism amid many assaults upon it. |