|

Table Mountain—The Native

Problem—The Land Problem—-Dr. Stewart as a Daysman—Native Criminal

Law—Race Enmity—The Scorners of the Natives—Hopeful Facts.

‘It is the aim of Christianity to

blot out the word alien and barbarian and put the word brother in its

place.’—Max Muller.

‘British justice, if not

blind, should be colour-blind.’—Conan

Doyle in ‘The Great Boer War.’

‘Contempt of men is the

ground-feature of heathenism.

‘—Marlensen’s ‘Ethics.’

‘Mega anthropos’

(A man is a great thing).—A

Church Father.

‘The great ones honoured

us, the believers showed us affection, but the people of the world

despised us because our skins were black.

‘—Gambella, the Christian Prime Minister of

King Lewanika of Barotsiland, on his return from the Coronation of King

Edward VII.

THE

first object that fixes the gaze of the

stranger at Cape Town is Table Mountain, that dark gigantic rock of

perpendicular granite, nearly 4000 feet high and 12

miles long. It besets him, monopolises attention, shuts

out all objects behind and dwarfs all in front, and looks menacingly upon

him through the windows of the house where he is sojourning. When the

white chilling mist lies upon it, that dark mass seems to shut out heaven

and overhang the whole city.

Since old Africa came to an end in

1900,

and Boer and Briton are now at peace, the native

problem confronts all thoughtful men in South Africa after the fashion of

Table Mount. It is the ‘black cloud’ which overshadows the patriot, and

for him there is from it no escape. It is the storm-centre of African

discussion and politics. And it had a large place in Stewart’s whole life,

and remained a permanent part of the horizon of his mind.

The native problem in South Africa

is the greatest of its kind in history, and one of the heaviest burdens

ever laid upon the white man. It will probably be the supreme test of

modern statesmanship. It may be fairly defined by using the words in which

a statesman recently described the kindred problem in India: ‘It is not a

phase but a development, not a sickness but a birth which our own

Government has created.’ The new wine is bursting the old bottles.

The essential facts are these:

Between the Cape and the Zambesi there were, according to the census of

1904, 1,142,563 whites and

9,163,021 natives and coloured people. Dudley Kidd, in his Kafir

Socialism (p. 284), says that the native population in Natal has

increased seventy-five fold in seventy years—from about 10,000 in 1838 to

700,000 in 1906. The natives have

an unconquerable vitality. The vices of the white men have failed to

reduce their numbers as they have done in other lands. They are still

‘fruitful and multiply and replenish the earth.’ The Basutos, the most

prosperous and intelligent of the African races, have, it is said,

increased fivefold during the last thirty years. In Natal, in twenty

years, the Zulus have doubled. Bryce, in his Impressions of South

Africa (p. 346), tells us that ‘the number of the Fingoes to-day is

ten times as great as it was fifty or sixty years ago. The blacks are

increasing twice as fast as the whites, as all the checks that formerly

kept the population in bounds have been removed.’ Dr. Carnegie says that

the negroes in America in 1880 were 6,580,793, and in 1890, 8,840,789. The

coloured races are multiplying with a rapidity which many deem alarming.

The problem is bow to develop the native into a citizen. Every year it

grows graver, and the penalty of failure is appalling. And it is very

urgent, for the natives do not move now as by the measured pace of oxen,

but as by steam and electricity.

[In his recently published

Kafir Socialism and The Dawn of Individualism: An Introduction to the

Study of the Native Problem, Dudley Kidd endeavours to set forth all

the essential facts in the problem, and to suggest practical remedies. It

is a very interesting book, but it is fitted to make the reader feel giddy

in presence of the enormous complexities, varieties, and hindrances which

belong to the native question. Mr. Kidd says that we are building up our

structure at the foot of a volcano, but that, like all Pompeians, we have

grown used to it, and do not worry much about our Vesuvius. ‘The problems

ahead,’ he says, ‘make one almost afraid to think.’]

There will soon be, if there is not

already, a pressing land problem. The territories allotted to the natives

are now almost fully occupied. While there are immense stretches of

unoccupied lands, the greater part of these is almost waterless, covered

with scrub, and incapable of cultivation. Our Empire in South Africa has

now reached its territorial limits. Africa now contains no more

unparcelled earth of any agricultural value.

It is not surprising that the

natives should be discontented when they see the land which belonged to

their tribes from time immemorial, now occupied by white men, some of

whom, they believe, are coveting the poor black man’s vineyard, and

wishing to ‘eat up’ his land. Some one has said that formerly Europeans

used to steal Africans from Africa, and now they are trying to steal

Africa from the Africans. The recent Boer war and the war in German

territory have tended to foster elements of discontent. And their rulers

admit that they have real grievances which should be remedied.

Many have written upon this

perplexing subject. A perusal of their writings leaves two impressions:

all admit the extreme gravity of the problem, and no one suggests a

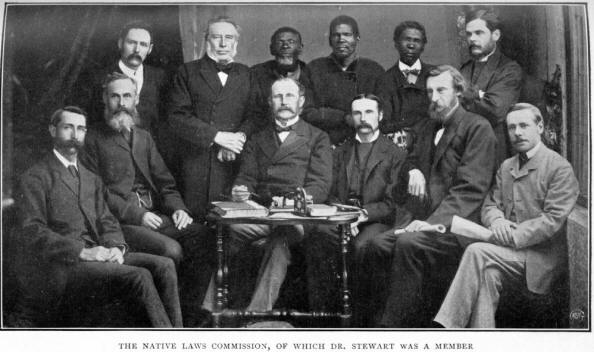

practical and hopeful solution. The Native Affairs Commission left this

question untouched. We are in presence of the growing pains of a new and

vast Empire. This spectacle has drawn the eyes of the world to South

Africa. We may hope that there will never be any serious war of races,

though some students of the problem have grave fears. There is a history

of Lobengula which has as its frontispiece a white and a black soldier

fully armed. It is plain to the eye that the black man has no better

chance in battle than the crow has with the eagle. Besides, the various

races know not how to unite, though they are now beginning to realise

their race unity and their common interests.

Stewart was well fitted to be a

Daysman between the conflicting parties. The ‘Great White Father’ of the

natives, he could lay a hand on both. The word ‘Lovedale’ had a charm for

them. It offered a fair field to all and no favour. There their children

ate, studied, worked, and played together with the white children. They

all knew that he had devoted his life to them.

[The Reverend Doig Young writes:

‘Once when Dr. Stewart and Mr. Mzimba were travelling together to attend a

meeting of Presbytery, they had to spend a night at a wayside inn. Knowing

that hotel-keepers as a rule do not give up a bedroom to a native, Dr.

Stewart, after being shown his room, asked the landlady what accommodation

Mr. Mzimba was to have. "Oh," she said, "I will let him sleep in the loft

outside." "Well, well," was the quiet rejoinder, "just let me see the

place." They were taken to the loft above the stable. Dr. Stewart turned

to Mr. Mzimba and said, in presence of the landlady, "You go and occupy my

room, and I will sleep here." "Oh no," was her reply, "I cannot allow

that." "But I insist upon it," continued Dr. Stewart; "if you have no

bedroom in the house to give my friend, he must take my room." The upshot

was that Mr. Mzitnba was shown into a comfortable room. During many years

this landlady told this wonderful story to her guests. It seems to have

been the only experience of the kind she had known.

‘Dr. Stewart was all through his

long missionary life the loyal and sympathetic friend of the native

people. He never forgot the old students either. Should he, even when

hurrying through the streets of a town to catch a train, notice an old

Lovedale lad on the other side of the street, across he would run at once,

shake hands, and ask after his welfare.

‘He lived, he worked, he prayed for

the advancement of the natives.’]

The chiefless native, without a land

or a home, formerly a man, but now a child in his new surroundings, and

bewildered with the white man’s strange ways, appealed strongly to his

knightly chivalry, and made him ‘think furiously’ as the French say. At

the same time Stewart’s attitude to the colonists had always been

respectful and propitiatory. Like them, he was a zealous imperialist, and

vehemently opposed to Kruger’s policy. Largely dowered with the God-given

instinct of revolt against oppression and wrong, he could express his

noble rage in the style of an Old Testament prophet. With flashing eye and

quivering voice he described scenes of wanton cruelty towards natives

which he had witnessed. The Grondwet (constitution) of the Transvaal,

which declared that ‘no equality between black and white was to be

recognised in Church and State,’ roused his intensest opposition. He was

thus persuaded that only under British supremacy could the natives receive

justice and consideration. [A friend who is perfectly familiar with the

subject writes: ‘Under and Constitution of the Transvaal, which is

supposed to be British, certainly has the approval of the Home Government,

the natives are said to no - no better off than when under Kruger. They

have political rights, and they cannot own property.] At the same time he

had no romantic or sentimental views about the natives. No man spoke more

boldly about their failings, and the exertions by which alone they could

improve their position. ‘It is not too much to say,’ writes Dr. M’Clure of

Cape Town, ‘that Dr. Stewart’s influence did much to ensure the adoption

by Cape Colony of the policy of equal rights for civilised men as citizens

independent of colour.’ This policy embraced the Glen Grey Act (so called

from the district to which it was first applied in 1894) by which the sale

of drink was forbidden to the natives. Cecil Rhodes was the chief advocate

of this policy, and he secured its application to Rhodesia. Many are of

opinion that in these questions he was largely influenced by Stewart. They

do wrong to Rhodes who represent him as a heartless exploiter of the

natives. He was ‘simply worshipped’ by his black servants, and he thus

defined his attitude to them: ‘The natives are children, and we ought to

do something for the minds and the brains that the Almighty has given

them. I do not believe that they are different from ourselves’

In 1888 Stewart had an influential

share in introducing a new era for the natives. Along with a leading judge

he was appointed to draw up a Bill codifying the native criminal law.

Their report extended to some seven hundred pages. A German had slain a

native, and for some time he was not called to account for his crime. The

Rev.

D. D. Don, of King William’s Town,

then boldly espoused the cause of the natives, and Stewart was one of his

chief supporters. The community was deeply stirred by the agitation, and

the principle was then for the first time fully established that in the

eye of the law the native had the same rights as the white man. This

successful agitation achieved for the natives of Africa what Burke, by his

action in the case of Warren Hastings, achieved for the natives of India.

Since then our nation has rejected the idea of geographical morality and

humanity, and has demanded that all the subject races within our Empire

shall be governed on British principles. That demand was made effective in

South Africa by the action of Mr. Don, Stewart, and their friends.

Stewart was a leading authority in

all matters affecting the natives, and he was often consulted by

statesmen.

Both Cecil Rhodes and Lord Milner

adopted the ‘Lovedale’ attitude to the natives. The following letter from

Lord Milner reveals his relation to Dr. Stewart and his matured

convictions regarding the natives:—

‘HIGH COMMISSIONER’S OFFICE,

‘JOHANNESBURG, Oct. 17, 1904.

‘DEAR DR. STEWART,—Many thanks for

your letter of October 6th, and for kindly sending me your book. The

contrasted maps on page 11 are striking indeed. I have so far read the

first and fifteenth chapters with much interest. You know that I am in

agreement with your temperate

hopefulness about the African, or at least the

African that I know. The Commission have been here the last ten days. I am

glad to find that the leading men on it seem to me to be inclining to a

very sound view; they are decidedly not anti-native, and are anxious to

give the natives both a chance and incitement to gradually rise

individually, and also to give them collectively some representation,

though they are dead against whites and blacks voting together. I think it

is going to come to native representation in a white assembly through

separate members elected by the natives, voting separately— not, perhaps,

an ideal solution, but better either than the present Cape system or the

total exclusion of the natives from all representation. The latter system

will no doubt continue to prevail for some time in the new colonies. One

cannot rush these things. But if the Cape, which has on the whole most

civilised natives, leads the way, and the experiment is a success, the

other colonies will doubtless follow suit in time. I hope you have by now

received the minutes of the evidence already given. You will be the best

judge whether you should appear before the Commission in person. There is

no man whose views on the native question would be of greater authority.

But, of course, you may think, on looking through the evidence, that the

considerations you would like to urge have already been sufficiently

presented by others. You alone can judge whether this is so or

not.—Believe me, dear Dr. Stewart, with affectionate respect, yours

very truly,

MILNER.’

In 1897, at Bulawayo, Rhodes made

his celebrated declaration about ‘equal rights for all civilised men south

of the Zambesi, whatever their colour.’ The policy adopted in Lovedale

forty years ago has been adopted in all the States in South Africa except

Natal, Transvaal, and Orange River Colony. ‘It has been given to few men

to make and mould a whole race ‘—we quote from the Memorial Number of the

Christian Express. ‘Such nation-builders God sends seldom. But Dr.

James Stewart, missionary, was thus honoured. It is to him, to his

largeness of soul, to his tenderness of heart all consecrated, enriched,

and purified by the spirit of God, that the native people of South Africa

owe in great measure the position of advantage and promise which they hold

to-day.’

Stewart was fully alive to all the

essential facts of the race-problem, which divides the English as well as

the Dutch. The attitude of many British colonials to the native was one of

the sorrows of his life. South Africa is, and has always been, a land of

extremes, contradictions, and surprises. To both Herodotus and Aristotle

is the saying attributed, ‘Out of Africa comes ever some new thing.’ To

the British traveller one of the greatest of African surprises is the

number of men of British birth who have no real sympathy with the native.

‘The traveller in South Africa,’ says Bryce, ‘is astonished at the strong

feeling of dislike and contempt—one might almost say of hostility—which

the bulk of the whites show to their black neighbours. The tendency to

race-enmity lies very deep in human nature.’

The whites in South Africa are much

more outspoken and unconventional than their kinsfolk at home. Their real

opinions are soon disclosed to the traveller. Some seem to regard the

black man as their haltered much cow, and scarcely a man. Their philosophy

is that Ham has no business to do anything but serve Japheth as in duty

bound. They forget that he has human feelings and rights. They expect him

to work for their profit with intelligence while he is not to use that

intelligence for his own advancement. They claim to speak for a large

number of their neighbours. It is here offered as personal testimony that

many intelligent Britons in South Africa say what no man would venture to

say in public at home. They value the black man only in so far as he can

be of service to them. One soon discovers in South Africa that inhumanity

may also have its bigots. Froude in his Oceana says: ‘A black man

is a better conductor of lightning than a white, and so a white has always

a black by his side in a thunderstorm.’ In his Last Journal

Livingstone says: ‘We must never lose sight of the fact that though the

majority perhaps are on the side of freedom, large numbers of Englishmen

are not slave-holders only because the law forbids the practice. In this

proclivity we see a great part of the reason of the frantic sympathy of

thousands with the rebels in the great Black war in America.’

It is true that the white man has

many provoking experiences with the natives, but has he none with his

fellow-whites?

In his evidence before the Native

Affairs Commission Stewart said: ‘The white man has contributed to race

antagonisms quite as much as the black perhaps. Many white people would

not worship in a church where the natives are. That is the general feeling

in the colonies.’

J. S. M’Arthur, Esq., the discoverer

of the Cyanide process of extracting gold, thus describes the scorn with

which some regard the native Christian: ‘As I began to mix more with the

people in South Africa, I got to understand the prejudice against the

Kafir Christian. Those who reviled him often knew nothing about him, and

those who really did know about him were, in most cases, a low type of

European who considered that every nigger requires to be kicked, beaten,

thrashed, and sworn at. The Christian Kafir had been taught that he was a

man, and he resented the continual ill-treatment. To the consternation of

the bully the "converted nigger" showed himself a man. The bully did not

like it, and then blamed Christianity for spoiling niggers.’

Sir R. Jebb, of the British

Association, reports that ‘the education of the native was spoken of by

some with scorn, or even with something like panic.’ They dislike native

education as much as the slave-holders did in the Southern States of

America. Surely he who opposes education cannot be regarded as an educated

man.

I met some whites in South Africa

who were deeply grieved that Lord Milner had heartily shaken hands with

native chiefs, and that statesmen and noblemen had entertained in their

houses in London the African chiefs who were at the Coronation. Though the

subject had a very sad side, the naïveté of the distressed objectors was

highly amusing. These people would deny to the natives the common

courtesies of life. Several representatives of the Press treat the whole

subject with heartless cynicism. In view of these facts, Britons should

not upbraid the Boers, as a class, for their treatment of the natives.

Some colonial objectors to missions

are like the peevish children in the market-place in Christ’s day. They

wish the missionary to teach the Kafir not to read but to work; and when

he is taught to work, they still object that the teaching heightens the

price of labour. Many are afraid of the competition of the trained native,

and think that he should be only a hewer of wood and drawer of water to

the whites, as patient as the ox and more obedient than the mule. [This

view is very frankly stated in the Koloniale Zeitschrift, the organ

of the German commercial company into whose hands the German Government

placed the development of their West African Territory. In that newspaper

we read: ‘We have acquired this colony, not for the evangelisation of the

Blacks, not primarily for their well-being, but for us whites. Whosoever

hinders our object we must put out of the way.’ Verily these men have had

their reward. (Christ us Liberator, p. 279.) ] The real trouble

with them is that they cannot get cheap skilled native labour, as the

education that makes it skilled, makes it also dear, and so prevents the

speedy enrichment of the white man. Like many unreasonable people, they

feel indignation in connection with one subject and express it in

connection with another.

It must be remembered that there are

two policies in South Africa, the Cape policy and the policy in Natal and

Transvaal. The policy of Cape Colony is British, that in the other two

States is more or less opposed to British ideals. During the Boer war many

in our country could scarcely believe that natives were not allowed to

walk on the pavement, and that if any attempted in Johannesburg to do so,

they were rudely driven away. But this great scandal has not yet been

remedied, and so Britain’s fair fame as the champion and protector of the

native races is imperilled.

We have now come to the gravest

element in this overshadowing, overawing, and omnipresent problem.

It is that pride of race and contempt of others which is the unfailing

mark of genuine barbarism. The low-minded scorners of the African race

forget that scorn breeds scorn and abiding resentment, and that the native

is a man for all that, of the same human stuff with ourselves. What can we

expect from them if to race-hatred of the raw Kafir there should be added

race-envy of the educated Kafir, whom some regard as a menace to the

imagined rights of the whites. Dr. Livingstone says that it is a very

dangerous thing to despise the manhood of the meanest savage, and that

some white men he had known had lost their lives by so doing. In Dr.

Blaikie’s Life of Livingstone,

p. 373, we find the following: ‘The rumour of the

Baron’s (Van der Decken) death was subsequently confirmed. His mode of

treating the natives was the very opposite of Livingstone’s, who regarded

the manner of his death as another proof that it was not safe to disregard

the manhood of the African people.' [A Brahmin was lately speaking to an

Indian missionary about the persistent scorn of natives by Englishmen,

which is believed to be largely responsible for the present estrangement

in India. The Brahmin added: ‘When you meet a real Christian the ideal is

possible, and it is possible nowhere else in the world.’]

In 1882 General Gordon, then

stationed at King William’s Town, wrote to Stewart: ‘Do away with the

unsympathetic magistrates and you would want no troops. To me the native

question is a comparatively simple one, if the Government would act at

once.’

The natives seem to have some

mysterious power which is lost by civilisation. Dudley Kidd calls it

telepathy. They know far better than the most intelligent whites what is

going on around them. ‘Among them the white man’s character and reputation

are as well known as if he walked in broad daylight with the whole story

written on his back.’ The natives now know all about the weaknesses and

vices of the whites. Do any of us realise what that means, or how the

terrible truth impresses them? Many are complaining that the natives do

not now respect the white men. But they warmly welcomed, and kissed the

hands of, the first white men who landed at Cape Town. No man should be

respected because his skin is white, or because he possesses superior

power. The natives respect all the whites who respect themselves, and they

adore those whom they can completely trust. To those who are saying, ‘We

must and shall have respect from the natives,’ the proper reply is,

‘Deserve it, and you will get it.’ Men do not gain respect by demanding

it.

Marvellous beyond words is the power

which the whites might easily gain over the natives if only their lives

were noble. ‘We perceive that you respect us, and we will be faithful for

ever,’ said the wild Beydurs of India to Meadows Taylor, their magistrate.

The hearts of all men are fashioned alike in this respect. Many great

statesmen and missionaries have shown how uncivilised men may be won. It

is very plain that they can never be won by brutality, coercion, and

scorn. It is the white man’s foolish haughtiness that rouses the demon in

the native and adds fuel to the fire over which native discontent is

simmering all the world over.

This barbarous colour-madness of

many of his fellow-countrymen came home to Stewart as a personal

affliction or a domestic calamity. C It is more difficult to say what will

be the future of the African himself,’ he says, ‘but it is possible that

the opinion about him will be as completely reversed as has been the

opinion of the civilised world about the continent in which he dwells. For

countless centuries he was regarded as only

fit to be a chattel

and a slave, and though that day is past, many at the present time regard

him as scarcely worthy of notice among mankind, except for his muscular

strength and fitness for the lowest and roughest kind of labour. Even

to-day educated Englishmen speak of him as an "inferior animal, as a blend

of child and beast," or a "useless and dangerous brute," scarcely

possessing human rights. To those who use such language I would say, how

badly we use the power and the gifts that God has given us, when we so

regard the unfortunate African.’

The Rev. R. W. Barbour wrote: ‘Dr.

Stewart has a great deal to do and to bear in his fearless defence of

their rights. He does not flatter the natives, but he does wish to see

fair-play, and to give them a chance of standing on their own feet in all

this hurry and press of Europeans, eager to get more land, and threatening

to override the coloured people altogether. Pitiably enough, the subject

is made here, just as at home, a matter of party.’

As this chapter is discouraging, it

should close with some words about the hopeful features of the native

problem.

1. As in India, the native

Christians, with extremely few exceptions, have never taken part in any

native wars, and they have often prevented bloodshed.

2. The leading statesmen and very

many of the citizens of South Africa desire to treat the natives with

justice and generosity. The Report of the Native Affairs Commission is

inspired by a noble desire to further the weal of all, and it will occupy

a place of high honour in history. But as so many are indifferent or

hostile, every question affecting the natives should be watched with

unslumbering vigilance in the mother-country. South African affairs are

now in a state of flux, and many are even proposing to remove the

restrictions on the sale of European liquors to the natives. Britons have

every right to secure that the natives shall be treated according to the

British ideals.

3. There is India with its

perplexing problems and its 300,000,000 split up into a hundred different

races, each speaking a different dialect, and all arrayed against one

another by caste, tribal and religious prejudices. The world has never

seen such audacity as that of our little island in undertaking to govern

there one-fifth of the whole human family, and success has attended the

effort because the Government has been just and sympathetic. ‘The

governing of India is a wonderful thing to contemplate; wonderful to

reckon by how few it is done, with what apparent ease and small parade of

power; wonderful to see how difficulties have been moulded into gains, how

prejudices have been turned to good account, and how strong bricks have

been made from uninviting straw. Above all are to be admired those broad

principles of justice, honesty, and kindness, which are at the foundation

of British rule.’ (Sir Frederick Treves, On

the Other Side of

the Lantern.) In spite of present

disturbances, India teaches us not to despair of Africa.

‘Make a man a man, and let him be,’

is the British method. The difficulties it entails are smaller than those

created by tyranny, as Russia and Belgium on the Congo know right well. If

there is danger in making concessions to an awakening people, is there

none in refusing them? Lord John Lawrence held that Christian things done

in a Christian way could never be politically dangerous. He declared that

these things, ‘so far from being dangerous, have established British rule

in India.’ ‘Having ascertained,’ he wrote in one of his despatches, ‘what

is our Christian duty according to our unerring lights and conscience, he

would follow it out to the uttermost, undeterred by any consideration.’

Niebuhr, the German historian, says

that Britons are the Romans of to-day. But there is an essential

difference: Britain desires to be, not the robber or mistress, but the

mother of the subject races. We may therefore hope that the native

question in South Africa will never, as in America, be settled by fire and

sword. |