|

It is most interesting to

observe the progress made during the first year of the operation of

National Insurance and to survey the actual progress with the criticism

of its opponents well in mind.

In the first place the

National Insurance Act was entirely experimental in this country. No

precedents could be invoked. The Act was necessarily complex in its

manifold details, although exceptionally wide powers were delegated to

the Insurance Commissioners in the shape of administrative, supervisory

and judicial functions. The Insurance Act directly touched the action of

nearly one-third of the entire British population, or some fourteen

millions of people. Not only was it enacted that weekly sums had to be

paid by or on behalf of these people, but their employers had also to

pay contributions and to perform weekly duties in respect of the

collection of the same. Both employers and employees had specific and

frequent duties laid upon them for active and individual observance. The

central administration had to organise an entirely new department of

work and procure and educate its staff. Advisory Committees had to be

formed. Insurance Committees had to be set up for each district.

Approved Societies had to be recognised and set in motion. A medical

service had to be instituted for each part of the country. The provision

of drugs and medicines had to be made. The public in general had to be

informed and educated as to the provisions of a new and complicated Act

of Parliament which cut in every direction into the life and duty of the

nation. In addition to all the difficulties inherent in the sheer

magnitude of this herculean task, destructive and querulous criticism as

to the merits of the Act, and more particularly as to some of its

details, had to be met. ,

An Act which should never

have been allowed to drift into the arena of party politics became a

bone of contention in the press and country, and every bye election

during the past year was fought not on the merits of the Act as a great

social engine of reform, but by party politicians exploiting any and

every grievance that any section of the community felt with regard to

any part of it. In addition to all the difficulties and opposition

engendered by different causes, the medical profession for a variety of

reasons avowed much dislike for and displayed violent opposition to the

conditions appertaining to medical service under the Insurance Act.

Resistance Leagues were formed to work against the Act and a malignant

and persistent opposition press fulminated daily against National

Insurance. The difficulties connected with starting the Act were so many

and the obstacles were so great that many people believed that the Act

would never start, or that if it did begin it would only be partially

operative and that a feeble beginning would end in an ignominious and

early break down. Prominent politicians publicly prophesied that the Act

would never begin. Others said it would not start inside three years.

Others pledged their reputations that it would be five years before half

the insured population would be in Approved Societies. Many others said

and believed that the deposit contributor class would consist of 10, 15,

20, 25 and up to 33% of the insured population.

No Act of Parliament was

ever launched amidst so many difficulties and against such hostile and

menacing opposition.

No Act of Parliament ever

achieved such magnificent and instantaneous administrative success.

The Commissioners threw

themselves with energy and ability into their gigantic task. Staffs were

organised. Leaflets and circulars by the million were printed and

circulated. Lectures were delivered to Societies and the public all over

the country. Advisory Committees were formed. Insurance Committees were

set up and quickly got to work. Societies of every kind were approved

and started operations in the most energetic and fruitful fashion.

Employers everywhere signified that they would obey the law, and many of

them, while keenly critical of the provisions of the Act, evinced great

interest in the work of the Approved Societies and the Public Health and

Tuberculosis crusade under the Act. The mass of the people joined some

kind of Approved Society, and only a very small proportion, for one

reason or another, drifted into the Post Office. The doctors, induced

probably by extra Government grants, took service under the Act. The

rods of the Resistance Leagues withered up and those of the Act

blossomed like Aaron’s. The National Insurance Act in its main great

outlines had come to stay and its successful initiation is at once a

triumphant testimony to the belief of the people in a national system of

insurance against ill-health, and a tribute to the fruitful labours of

those who are working for the prevention and cure of sickness, for the

healing of the nation, and for deliverance from the scourge of the white

plague. The common-sense and law-abiding instincts of the British people

provided a colossal rebuke to the meaner spirits who guided an

unscrupulous agitation against a great scheme for the national welfare.

To Mr. Lloyd George, as

he watched the fate of his child, the months must have been anxious

ones. But he won through in a great triumph. It was after the storm in

his native woods that he sought for and gathered ample stores of

firewood. And now, after the tempest of criticism, he is gathering- the

gratitude of hundreds of his fellow citizens, secured as they never were

before against all that menaces their health and consequently their

comfort. He is almost in the enviable position of the man who makes the

songs of a nation.

In connection with the

initiation of the Act, it should be remembered that Sanatorium benefit

was the only benefit which was immediately operative in July, 1912.

During' the first year, in the United Kingdom, nearly 20,000 persons

received the benefit of some kind of treatment in connection with

Tuberculosis. More definite information for a portion of the year is

contained in a table which is taken from official sources and which is

incorporated in these pages.

Medical benefit began to

operate in January, 1913, and since then on the average in the United

Kingdom nearly 500.000 persons have received medical treatment and

attention every week.

Sickness benefit started

in January, 1913, and on the average in round figures 270,000 persons

have received weekly sick pay in the United Kingdom.

Maternity benefit also

began in January, 1913, and nearly 18.000 maternity benefits have been

paid weekly.

In six months a sum

approaching 2,500,000 has been paid in treating insured persons who were

receiving medical benefit. In the same period nearly two-and-a-half

millions have been disbursed in payment of sickness claims. In half a

year nearly half a million of maternity benefit has been paid.

PROGRESS OF THE ACT IN

SCOTLAND.

The following details are

taken from official sources of the actual progress made in initiating

the National Insurance Act in Scotland :—

Sale of Stamps.

The amount received from

the sale of health insurance stamps in Scotland up to the 11th July was

;£2,040,000. To these receipts there would fall to be added Government

grants both special and those of two-ninths (or one-fourth) of the cost

of benefits and administration.

Expenditure upon

Benefits, etc.

The Amount advanced by

the Scottish Insurance Commissioners to Approved Societies up to 15th

July was ,£710,604, of which ^'4-16,810 was for benefit and ^263,794 for

administration. Advances to Insurance Committees totalled ^'322,992. The

amount paid in respect of claims by deposit contributors up to the same

date was £377 in sickness and ^85 in maternity benefit. It will be

observed from the foregoing figures that the average claim for sickness

and maternity benefit by deposit contributors has been only 3d. per

head, a shrewd comment on those critics who promised us a welter of poor

lives in this section of the scheme.

IV. INSURANCE COMMITTEES

IN SCOTLAND.

The number of Committees

and their aggregate membership may be summarised as follows :—

The number of burgh

Committees is now twenty-five, owing to the Committees for the burghs of

Govan and Partick having ceased to exist in consequence of the recent

extension of the boundaries of the city of Glasgow.

One result of the

constitution of Insurance Committees is a considerable accession to the

number of persons interested in the local administration of the country.

To the extent of one-fifth the members were already members 'of Town and

County Councils. But, as regards the rest (2,000), it may be assumed

that a large proportion had not previously served on any public local

bodies.

V. MEDICAL BENEFIT IN

SCOTLAND. Formation of Panels.

On the 15th January,

1913, when medical benefit came into operation, there were local

difficulties still remaining for adjustment, to which reference will be

made; but in Scotland generally the panels constituted were 'adequate,

and were capable of affording competent medical attendance and treatment

to insured persons.

Further additions were

made to the members on the medical lists during the early weeks and

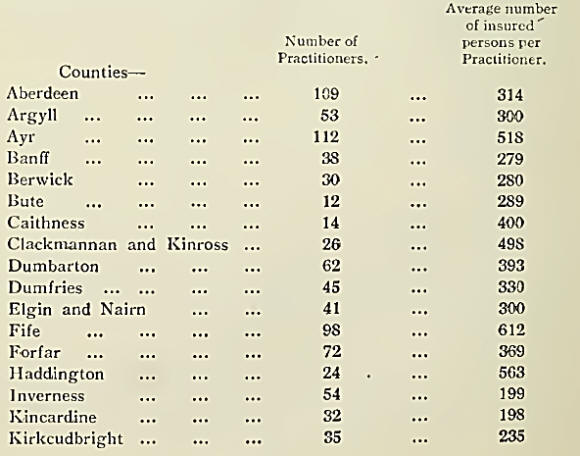

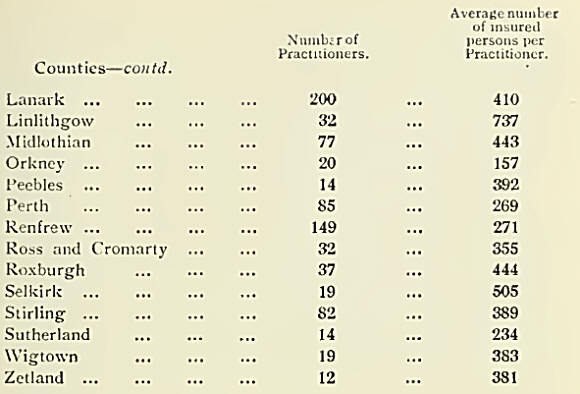

months of 1913. The following table shows the number of practitioners on

Scottish Panels as at March, 1913, together with the average number of

insured persons per practitioner for each Insurance Committee.

Practitioners on

Medical Lists, Scotland, at March, 1913:—

As regards the number of

persons receiving- attendance from each insurance service practitioner,

in five Counties there

are more than 500 insured

persons per practitioner, and in nine more than 100. Among- these, the

highest number is in Linlithgow, with an average of 737; the next in

order is Fife, with an average of 612. The remaining 22 county areas

have 400 insured persons or less per panel practitioner. Orkney,

Kincardine, and Inverness are all below 200.

In the burgh group the

majority of Burghs—21 in number —show between 400 and 1,100 insured

persons to each insurance service practitioner. Two burghs show less

than -100: Rutherglen with 255 on an average, and Wishaw with 274. Three

burghs show more than 1,000, namely Clydebank with 1,006, Paisley with

1,231, and Dundee with 1,638 insured persons, respectively, per

practitioner on the medical list.

Mileage.

Considerable discussion

has been aroused in Scotland among medical practitioners in country

districts as to their relative disabilities as compared with urban

practitioners, more especially the difficulty caused by sparseness of

population and deficiency of means of locomotion. It is now admitted

that the advent of the motor car has solved many of these difficulties,

although some expense is entailed by the upkeep of a car. The following

passage on mileage is taken from the Report of the Scottish Insurance

Commission :—

“Mileage is the distance

which has to be travelled by doctors in order to visit their patients.

It is that which has to be annihilated in order to place doctors who are

remote from insured persons on an equality with those who live closer by

them.”

The question of mileage

is not one of distance merely, though the distances travelled by doctors

in Scotland are often remarkable. It involves such further consideration

as deficiency or absence of roads, crossing of moors or mountains, and

frequently passage by water. It is closely related to economic

conditions, especially in the Highlands, of which it may be said that

wherever the doctor’s journeys are longest and most arduous, the means

to lighten the burdens of travel will be found to be least available.

At a Conference held on

25th and 26th November, 1912, between the Chancellor of the Exchequer

and a deputation from the British Medical Association, the subject of

financial provision for mileage, over and above the redistribution

permitted under the Medical Benefit Regulations, was put forward for

consideration. It was recognised by the Government that in some parts of

the country which are exceptionally sparsely populated, and in which

there are special difficulties of access (such as mountain, bog, and

moorland), practitioners would be placed at special disadvantage, and it

was decided to ask Parliament to provide a special fund to be applied by

the Insurance Commissioners in making increased provision for such

areas.

Thereafter, at a meeting

on 3rd January, 1913, which took place in London between the Chancellor

of the Exchequer, the Commission, and the Chairmen and Clerks of the

Scottish County Insurance Committees the subject was again under

discussion. A small Committee was formed consisting of the Chairman of

Renfrew County Insurance Committee, and the Vice Chairman and Clerk of

Lanark County Insurance Committee, to procure from the various Scottish

County Insurance Committees information which might be of value in

dealing with the question. Schedules of enquiry were drawn up and issued

by the small Committee through Clerks of County Insurance Committees to

doctors in County areas throughout Scotland. The doctors were asked to

furnish on these schedules an approximate statement of the miles which

would require to be travelled by them, the miles being measured from the

nearest available practitioner on the panel. Miles were to be regarded

as of two varieties, normal miles, that is to say miles beyond three

measured along a driving road ; and special miles, that is to say miles

beyond three of any of which a quarter or more could not be so

travelled, but only on foot, as on hill or moor, and exceptionally by

ferry. These returns were duly furnished, and, though somewhat

approximate and in a number of cases incomplete, they proved of

considerable service by indicating the numerical scope of the problem as

it presented itself in Scotland.

Lowlands.

Apart from the Highlands

and Islands, for the sparsely populated rural areas of Great Britain a

mileage fund of p£50,000 has been voted. The share of this fund which

will fall to Scotland, excluding the Highlands and Islands, is ^1G,000.

While the Highlands, for the purposes of the Medical Service Committee

were properly demarcated from the Lowlands on the ground of the

straitened circumstances of the people, it would nevertheless be

inaccurate to conclude that in sparseness of population, ruggedness of

contour, want of railway communication, difficulty of road transit, or

rigour of climate the Highlands cannot be matched by certain portions of

the area which, for convenience of reference, is here entitled the

Lowlands. The eastern extremity of the Grampian Range intrudes into

Banffshire and Aberdeen, and the highest summit but one in the British

Isles is situated in the latter county. The rigorous winters at

Tomintoul are well known. Strathdon, where the doctor has to travel by

sleigh for several months each year has already been referred to. The

conditions prevailing in Arran and in the Border and Southern Counties

have been under the notice of the Commission. The whole Lowland area

outside the towns is essentially sparsely peopled.

Precise details remain to

be ascertained. It is the purpose of the Commission to take immediate

steps to investigate Lowland mileage by an expeditious method. The

object of the enquiry will be to ascertain a basis for distribution of

the grant with a view to its apportionment among individual doctors as

speedily as possible.

By Regulation 50 of the

Medical Benefit Regulations, an Insurance Committee may, if they think

fit, make arrangements for a payment to practitioners on the panel in

respect of mileage, such payment, by Regulation *10 (3), being deducted

from the Panel Fund for disbursement among doctors who attend insured

persons resident at such distance as may be determined. The financial

procedure involved, though nominally a deduction, is in effect a

redistribution of a portion of the Fund for the benefit of medical men

who have distances to travel.

The provision referred

to, which is in addition to, and not in place of, the subsidy which will

be payable from the Treasury Grant for mileage, was adopted by agreement

between the Insurance Committees of Lanarkshire and Midlothian and the

medical practitioners of these Counties. It was decided that the sum of

2d. per insured person per annum should be reserved to form a County

Mileage Fund. It is intended that the rate of payment shall, as far as

practicable, be Is. Gd. per mile over three from the doctor’s residence,

measured along a driving road.

HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS

MEDICAL SERVICE COMMITTEE.

In many respects

including National Insurance the Highlands and Islands of Scotland

constitute one of the most difficult administrative problems of the

whole of the United Kingdom. It should always be borne in mind that a

relatively small proportion of the Highland population is employed in

the sense of the Act and that a combination of difficulties exist which

is not to be found elsewhere in Great Britain. The following from the

Scottish Report presents a good idea of the problem :—

“On the 11th July last

the Highlands and Islands Medical Service Committee (of which the Deputy

Chairman of the Commission was a member and one of the Inspectors the

Secretary) was appointed to investigate conditions in the Highlands and

Islands. In the absence of a definite indication in the terms of

reference as to the exact area to which the enquiry was to be confined,

the Committee determined to take evidence from the counties of Argyll,

Caithness, Inverness, Ross and Cromarty, Sutherland, Orkney and

Shetland, and from the Highlands of Perthshire.

“In the Committee’s

Report, which was submitted on the 24th December last, the circumstances

which made medical provision in the Highlands and Islands a special

problem were stated to be as follows :—

(a) That on account of

the sparseness of the population in some districts, and its irregular

distribution in others, the configuration of the country, and the

climatic conditions, medical attendance is uncertain for the people,

exceptionally onerous or even hazardous for the doctor, and generally

inadequate.

(b) That the straitened

circumstances of the people preclude adequate remuneration of medical

attendance by fees alone.

(c) That the insanitary!

conditions of life prevailing in some parts render medical treatment

difficult and largely ineffective.

(d) That in default or

disregard of skilled medical advice and nursing, recourse is not

infrequently had to primitive and ignorant methods of treating illness

and disease. These methods are a source of danger, especially in

maternity.

(e) That there is danger

of physical deterioration from defective dieting, and more markedly in

the infant and juvenile population.

(f) That rural

depopulation is not a feature of the whole area of the remit, and thatl

even where notable, the necessity for medical provision is not

materially reduced.

(g) That the local rates,

from which the doctors’ income is mainly derived, are in many cases

overburdened.

(h) That owing to the

industrial conditions the Insurance Act is only very partially

operative.

(i) That, in short, the

combination of social, economic, and geographical difficulties in the

Highlands and Islands—not to be found elsewhere in Scotland—demand

exceptional treatment.

“The quality of the

country is specifically referred to as rugged, roadless and mountainous.

Where not composed of islands, it is described as very largely

peninsular on the seaboard, and broken up inland by lakes and rivers.

“Adverting to the

Insurance Medical Service, the Committee state that they are convinced

that the industrial conditions of the area are such as to make the

provisions of the Insurance Act less operative than in other parts of

Scotland, and they foresee considerable trouble in providing medical

benefit for fully-insured persons far removed from a medical centre.

They express the view that special subvention for the insured would

appear to be necessary, and that the provision of medical attendance for

their dependants is also a matter requiring urgent consideration. It was

clear to the Committee that, having regard to the economic conditions

prevailing in the Highlands and Islands, the extent to which medical

services are at present subsidised from Imperial funds is quite

inadequate, and that as local resources are in many parishes already

well nigh, if not wholly, exhausted, any general amelioration of the

existing medical service cannot be achieved without a further and a more

substantial subsidy.

“In subvention of the

Insurance Medical Service there was voted in the Special Grant-in-aid to

Scotland for 1912-13 the sum of ;£l0,000 for the Highlands and Islands

for mileage and other special charges. In order to make this money

available at the earliest possible moment to medical men in the

Highlands and Islands the Commission, through their Inspectors, are now

engaged in obtaining data to enable them to prepare a scheme for its

distribution on an equitable basis between the County Insurance

Committees concerned. For the purpose of enquiry, the provisional

standard is a three-mile limit from the residence of the nearest

available insurance service practitioner, but all sea journeys are being

noted, whether within or without three miles. The basis of distribution

to medical men within counties will be determined as soon as possible

after the enquiry is completed.

“It should be observed

that the ^10,000 is not for mileage only, but for special charges also.

These terms of the Grant, provided the fund suffices, will give an

opportunity to treat cases of exceptional hardship with the

consideration which they may be found to merit. Cases of difficulty and

danger in the medical service of the Highlands and Islands have come

under the observation of the Commission.”

It only remains to be

added in this connection that as a result of the National Insurance Act

and the investigations and recommendations of the Dewar Committee, an

Act has been passed to provide a special parliamentary grant of ^"42,000

a year to aid in improving the medical service in the Highlands and

Islands, and a special Board has been constituted to administer this

fund and to administer schemes for the improvement of the medical

service in the district concerned. Great hopes are entertained of a much

needed improvement in the medical service of the Highlands and Islands

of the North of Scotland.

CHEMISTS.

The provision and supply

of proper and sufficient drugs and medicines and prescribed appliances

to insured persons is one of the duties of every Insurance Committee.

No difficulty was

experienced in Scotland in arranging for this supply. Scotland has been

fortunate in having in the pharmacy profession an excellently trained

service who have deservedly won high reputation for skill and integrity.

Some attempts have been made in various quarters to suggest that some

Scottish chemists were supplying inferior drugs and medicines for the

use of insured persons. Not a shadow of proof was ever forthcoming for a

charge which is not now heard. On the contrary we have direct testimony

that Scottish chemists continue to dispense drugs and medicines of the

same high quality as they formerly supplied, and indeed as they were

bound to supply according to agreement and the law of the land. The

following- statement of the position of chemists is taken from the

Scottish Commission’s Report:—

“The position of chemists

in Scotland with respect to service under the Act is believed to differ

in some degree from that of their professional brethren in England. It

is understood that in the past throughout England generally the supply

of drugs to patients by medical men has been the prevailing custom, and

in certain districts the almost unbroken rule, not only in country

places where no pharmacist was established, but also in cities where the

services of chemists; could readily have been secured. In Scotland, on

the other hand, while doctors in remote and solitary places have

dispensed their own medicines, they have done so under the constraint of

circumstance, and the great majority of medical men in towns and other

populous areas have been content to leave the work to chemists.”

It is understood that in

England, as contrasted with Scotland, the amount of medicine consumed

per patient is higher; that the period for which mixtures are prescribed

to last is shorter, leading to more frequent repeats and consequent

dispensing fees; and that the proportion of mixtures, which are quickly

made up, to such preparations as pills and powders, which take some

time, is very considerably greater.

So it has come to pass

that the Act, by drawing a line of separation between medical treatment

and the provision of drugs, has directed into the hands of English

chemists an. increased volume of trade, without conferring upon Scottish

chemists an equal or corresponding advantage. It has been alleged by

pharmacists in Scotland generally that the Act cannot increase their

custom ; and on this ground, it is presumed, they have been disposed to

praise the tariff of charges somewhat faintly.

The Commission were

informed that investigations made by Pharmaceutical Committees and

others in important Scottish centres appeared to show that the tariff of

prices was likely to leave the Drug Fund of the areas concerned at the

close of the year with an appreciable balance to carry forward. A

supplement to the tariff was submitted by the Secretary of the

Pharmaceutical Standing'

Committee. The Commission let it be known that they were prepared to

approve the supplement, which rectifies certain inaccuracies. They also

said that, if at the end of twelve months it should be found that there

was an unexpended balance in the Drug Fund sufficient to justify an

additional proportionate retrospective payment not exceeding 10°/o on

the amount of the accounts of individual chemists, they would consent to

such additional payment being made as might be approved by themselves

and the Insurance Committee.

In reply to a request

that they would indicate their readiness to consider a stated case in

regard to an increase in dispensing fees, a general revision of tariff

prices, and payment for postage or carriage of medicines for insured

persons in rural areas, the Commission explained that while they would,

at any time, be glad to give careful consideration to such

representations, they would deprecate any amendments being made until a

year’s experience of the working of the tariff has been obtained. They

assumed that any proposals as regards revision of tariff prices had

reference only to an annual revision as at the date of the agreements,

and not to a scheme of adjustment of prices to follow market

fluctuations. Any suggestions on the last-mentioned lines they would

deem impracticable.

Representations were made

to the Commissioners by the Pharmaceutical Standing Committee (Scotland)

with respect to Regulation 30 (1) of the Medical Benefit Regulations, in

so far as it permits doctors to claim the right to supply medicines to

insured persons residing in a rural area more than a mile from the place

of business of a chemist who is on the list of an Insurance Committee.

The Standing Committee expressed the view that the Regulation, in so far

as it gives such permission, should be repealed. The Commission stated,

in reply, that they would afford every assistance to the Pharmaceutical

Standing Committee in submitting the special position in Scotland and in

explaining the difficulties which have been raised there by this

provision of the Regulation.

The procedure for dealing

with drugs, as opposed to appliances, in connection with pharmaceutical

service under the Act, was the occasion of frequent enquiries addressed

to the Commission.

By Regulation ‘28 of the

Medical Benefit Regulations, the Drug Tariff is the list of prices for

drugs ordinarily supplied and for prescribed appliances. There are other

drugs not on the Tariff, which may be ordered also, and the manner of

calculating payment for these is provided for in the Regulations ; but

there are no appliances permitted to be provided other than the

prescribed appliances, which by Regulation 27 are stated to be the

appliances mentioned in the Second Schedule.

The difficulties of

chemists in handling prescriptions ordered under this head were

appreciably increased by the circumstance that the tariff of prices of

appliances put forward by the Pharmaceutical Standing Committee was not

co-extensive with the Schedule. Splints, for example, are named in the

Schedule simpliciter; leg splints, therefore, may be ordered though arm

splints only are priced in the Tariff.

These considerations

ruled the decision as to the correct form to be used for ordering.

Prescriptions for drugs were to be entered on the green or pink form,

respectively, according as their component substances were or were not

all included among drugs priced in the Tariff; but all appliances

permitted to be ordered, whether priced in the Tariff or not, were to be

ordered on green forms. Appliances not included in the Second Schedule

to the Regulations were not to be ordered at all.

During the early days of

the operation of Medical Benefit, statements were circulated in certain

quarters to the effect that the pharmaceutical service of the Act was

such that insured persons must necessarily be supplied with drugs of an

inferior quality.

This statement is

incorrect. The conditions of the agreements entered into by chemists

with Insurance Committees expressly stipulate that all drugs shall be of

good quality, and any chemist failing to observe the terms of his

undertaking to the detriment of the service will be liable to have the

question of his continuance upon the list of chemists reported upon by

an Enquiry Committee appointed by the Commission.

Drugs duly ordered are to

be supplied to the insured persons by the chemist, the cost being

defrayed out of the Drug Fund at the prices set forth in the Tariff. It

is important to note that the Drug Tariff is not an exhaustive list of

the drugs which may be ordered for insured persons : it is a list,

prepared for the sake of convenience, showing the prices agreed to be

paid by an Insurance Committee for certain drugs if ordered. Drugs which

are not included in the Tariff, but which the doctor may consider

necessary for the proper treatment of the case are ordered in a special

manner, and their cost also forms a charge upon the Drug Fund :—

The number of chemists on

the lists of Insurance Committees in March, 1913, is shown in the

following table:—

|