|

TWO letters, written by Dr

Legge soon after his arrival in Hong Kong, give a glimpse of struggle and

straitening.

'Hong Kong, Nov. 13, 1843.

I have not been able to save

a farthing, nor do I see that I shall ever be able to do so. And yet there

were months together, in Malacca, when we had only a little rice and some

boiled or fried fish for dinner. I can only do what I can—make every effort

to make ends meet—give my children a good education and leave them an

unstained name. The missionary, who will simply walk within the line of his

proper duty, can save money only in very peculiar circumstances.'

iJune 17, 1844.

'Our expenses in removing

from Malacca to Hong Kong have been very considerable, and here they have

been very heavy, principally on account of so much sickness; and our losses

have not been small. I bought a goat in Malacca for 12 dollars, just before

I left, to give us milk on the voyage. She and her kid died soon after our

arrival here, because we had no proper place to shelter them in. When Mary

fell ill and we were about to remove into a house of our own, I bought a

Chinese cow and her calf for 30 dollars; the calf died soon after in a

small, damp, new-built place, the only place we had for them. The cow as a

consequence—they are not like cows trained at home—ran dry immediately, and

I changed her for another cow and calf, giving 12 dollars in addition. That

calf died in the same way, and now a mutchkin of milk a day would cost

nearly six dollars a month, but we do the best we can to drink our tea

without any.'

Their early days in Hong Kong

were also disturbed owing to the unsettled state of the island.

One night they were awakened

by an attack of Chinese burglars. A number of them collected outside and

threatened to force their way in and plunder the house unless money were

handed out to them. Dr Legge replied, 'If you break in, it will cost at

least two of you your lives,' and thrust the barrel of his rifle through the

Venetian blinds. For about half an hour the burglars walked round and round

the house, trying every door and window. Unable to effect an entrance, they

went up the hill a little distance, made a bonfire of every combustible they

could collect, danced round it, and went away. A week or two before, a large

band of robbers had broken into a house across the street. One of the

occupants succeeded in getting to the Police Station and giving the alarm.

Half a dozen policemen went up with guns and found the burglars in

possession of the plate-chest, several having already run off with booty to

the shore where the boat was lying in which they had come from the other

side of the harbour. The chief policeman ordered his men to fire. Dr Legge,

being awakened by the shots, came across from his own house to find a scene

of confusion, with the leader of the burglars bleeding to death on the

floor.

Hong Kong, Feb. 25,1844.

*1 am very happy in my work.

I opened a new chapel in the heart of the Chinese population in January

which is attended in a very encouraging way. A-fat, the first Chinese

Protestant convert, is labouring with me. I have plenty of work too in

visiting the Chinese. This is a most interesting department of missionary

labour and a most difficult one. It requires an easy address which I sadly

want, and much tact—much acquaintance with human nature, and consistency of

Christian character. By and by, I hope to see a flourishing school and a

Theological Seminary, with an Institute for native girls, all flourishing

here. My hands will be full.'

Hong Kong, Oct. 25,1844.

'I have been ill with fever

and brought very low. For two days it seemed that my work in time was done.

I was bid to look more directly in the face of eternity than I had done

before. But, oh, how little satisfaction did the contemplation of my past

life give. I trust I have received an impulse from this last dealing of God

with me that will not cease with my life. A sincere, simple, watchful,

humble, devoted missionary's career must and will be my aim. God has brought

every member of our mission through the furnace during the first year of our

labours in China, and I trust it will be seen that we have all been

refined.'

Recovering from this illness

he resumed work. The following letter shows the uncertainty of communication

with the East at this time.

Hong Kong, April 8, 1845.

'My Dear John,

'Since I last wrote I have

received William's letter of October and yours of the 27th of September. The

former came to hand nearly a month before the other—the vessel which was

bringing the September mail having been wrecked on the coast of Java. As my

command of the language increases, so do my engagements. Nearly every day I

spend two hours at least visiting, distributing tracts, and talking till my

tongue is really tired. I expect ere long there will be a large gathering of

the natives round us. Two of my old pupils followed me up last month from

Malacca.'

Here is an idyllic picture

which falls into the year 1845, just a little before his compulsory visit

home on account of health. Those who knew Dr Legge, can so well picture him

sitting in the alcove.

'Last month I paid a visit to

Canton, and was exceedingly struck with the opportunities for missionary

labour which that populous city affords. I am convinced that any amount of

work can be carried on in it, with ordinary prudence. I took with me 3000

copies of two-sheet tracts upon the ten commandments, 2500 of which were

distributed in six days. A Chinese merchant took a friend and myself one day

an excursion, to visit some celebrated flower-gardens, about three miles up

the river from the factories. It happened to be the day for visitors, and

the walks were crowded. On my suggesting to my native friend, that I should

like to distribute some tracts among the people, and speak to them about the

doctrines of Jesus, he at once bestirred himself, and circulated the

intelligence throughout the gardens. I sat down in a small portico, at a

corner of one of the walks, while the people passed along in files in front

of it, each individual receiving a tract, and collecting, every now and

then, into companies of from thirty to fifty, to hear it explained. In this

way 500 tracts were distributed. It was an interesting fact to reflect, that

five hundred immortal beings had that morning, for the first time, learned

their duty to their Maker, and heard of One who came from heaven to earth to

seek and to save them. May the seed that was thus sown be found after many

days!'

In 1845, however, Dr Legge

was obliged, after long and severe attacks of fever, to return to England

with his wife and two daughters. He was also accompanied by three of his

Chinese pupils.

Hong Kong, Nov. 18,1845.

'Our luggage is all on board

the Duke of Portland and we are likely to sail to-morrow. It is with much

reluctance that I quit this post. Just as the machinery requisite to

effective operations in our work has been completed through my labours, and

a course of action has been commenced which bids fair to be crowned with no

ordinary success, I am called to put off my armour and retire. But if the

experience of the last six years has taught me anything, it is these two

lessons—that God will be all in all, and that there is in the human mind

such a tendency to self-exaltation, self-confidence, that we ought to

welcome any dispensation of Providence, however afflictive and mysterious,

by which it is repressed.

'It is with much pleasure I

hail the quiet months of the voyage. Oh, the luxury of unbending the mind

after six years of unusual tension. I have had no repose—no rest since I

left home. You know I am bringing home three Chinese boys with me. They must

just go to school as other boys. The principal object is that they get hold

of the English, so as to be able to read it with intelligence and to speak

it'

These three lads in due time

returned to the East and maintained there a Christian character and

reputation. One of them, Song Hoot Kiam, filled for many years the

responsible post of chief cashier of the P. and O. Company at their station

of Singapore. In 1890, when Dr Legge's second son visited Singapore, he

received much hospitality from him. Song Hoot Kiam still spoke English

perfectly, and was only too delighted to see and entertain his old friend,

Dr Legge's son.

The two years at home

restored the missionary to vigour, though then, as ever, idleness was to him

unknown. Indeed, the holiday of a missionary meant to him little but hard

labour. He travelled here, there and everywhere, preaching and addressing

meetings.

Dunfermline, Nov. 6, 1846.

'I preached three times in

Stirling on Sabbath and had a public meeting next day. On Tuesday morning a

long walk round Stirling Castle, anything more magnificent I have never

enjoyed. In the afternoon a beautiful sail down the Forth to Alloa and a

meeting there in the evening as good as could be expected on a tempestuous

night in Scotland. Yesterday we came on here: a meeting of spirit and

productiveness last night. In half an hour we drive to Inverkeithing for a

meeting there. All the day I have enjoyed myself exceedingly. My lodging is

with Professor MacMichael of the Relief Church. A delightful stroll over all

the ruins and antiquities of this place. I have stood on St Margaret's

shrine, upon the Bruce's grave, and under the shade of an upshoot from the

root of the tree that Wallace planted on his mother's grave. A mavis and

half a dozen chaffinches were pluming themselves among the branches; a rich

inheritance in nature and in the associations of history.'

DR. LEGGE AND HIS THREE CHINESE STUDENTS.

From a fainting by H. Room.

Here is another letter in

homely vein, to his brother John, which will illustrate the difficulties of

travelling.

London, Dec. 26, 1846.

'I must give you some history

of my journeying. I started from Huntly determined (D.V.), if my health

stood out, to have my Christmas dinner here with Dr John Morison of Brompton.

I succeeded, though things seemed more than once, as determined as I was, to

baulk the realisation of my purpose.

'After writing to William for

Mr Leslie, I walked down to the office of the Newcastle steamer, and there

outside was a notice: "Will sail on Thursday at 4 p.m." In fact, I found she

had not got back from her trip of the week previous, and the Thursday's

sailing was a mere contingency. Off I went to the coach office, and found

the mail started at three, but demurring to the expense, I proceeded to the

packet office and took my place in a Leith schooner. She was to sail at

three o'clock, and there I was quietly and comfortably waiting for the

lifting of the anchor, when I heard a whisper that the bar was very rough.

The master, when questioned, said he was prepared to sail, but did not know

whether the tug could tow them out. To the tug I went and got the master of

it to take his vessel out and have a look at the bar. Back he came, and the

word was: "No towing across the bar to-day." I ran with all my speed to the

hotel, and was just in time to catch the mail on the start. I thought I

could ride outside to Edinburgh, but by the time we reached Montrose I had

no more life in me than a huge icicle. So then I got ensconced inside, and

we reached Edinburgh in time to be an hour too late for the 5 a.m. train.

There was no help for it but to make a comfortable breakfast, and be in

readiness to start a quarter past 8. The snow was lying prodigiously deep

between Stonehaven and Montrose. We reached Berwick at half-past 10, and I

got upon the coach expecting to be in Newcastle by 6, and was luxuriating in

the anticipation of a good dinner and a warm bath. But down came the snow

and nearly blocked our way. Eleven hours we sat upon the coach, and reached

Newcastle 40 minutes too late for the train. A special one was started about

eleven. A cold and dreary night it was, but all was forgotten in the light

of the radiant countenances that beamed upon me here between one and two

o'clock.'

London, March 5,1847.

'I have more than enough upon

my hands. My engagements for this month are just twenty-five. On Tuesday

evening we had a magnificent meeting. Every hole and corner was crammed,

stairs, passages and all. There could not be fewer than 2500 people present,

and another thousand went away. I was the chief speaker of the evening.'

Falmouth, 27, 1847.

'Several friends down here

set up a roaring, as if they had been so many bulls of Bashan, at my not

coming to fulfil my engagements, that I was obliged to start for Exeter by

the express. Thence I came by coach to this town—a ride of 105 miles. We

were twelve mortal hours upon the road. I got to Falmouth about four o'clock

in the morning; not like "patience on a monument smiling at grief," but

impatience impersonate on the top of a coach, wan and weary, with head half

sunk between the shoulders, hands pushed to the very extremity of greatcoat

pockets, knees crunched together, and teeth firmly compressed to prevent

their chattering. All's well, however, that ends well. I have slept and

breakfasted, and am ready for action.

'God knows my supreme desire

is to return and serve Him among the Chinese. I desire to feel that His will

concerning us is not a series of arbitrary resolutions, but determinations

for the wisest and the best, to which our ignorance and wilfulness must bow

with praise and adoration.'

Leicester,. 24,1848.

'I preached here (where his

brother, the Rev. Dr George Legge, was minister), twice on Sabbath, and

lectured on Monday evening upon China. Tuesday morning took me and the

Chinese lads to Manchester, where I preached in the evening at an

ordination, and next night was the best public meeting, many people said,

that they had ever had in Manchester. The same evening we went on to

Rochdale, and thence on Thursday to Hull. There we had an overflowing

meeting. On Saturday we came on here, and I addressed about a thousand

children in the afternoon and preached in the evening. A meeting to-night,

for which I have retained the lads, but to-morrow I shall send them on to

London, following myself on Thursday. The fatigue and excitement have been

too much for them, and for myself also.'

He had already written to his

father—'I have had a sufficiency, I am sure, of travelling and journeying

through England. It will be something to call to mind on the other side of

the earth the various public meetings which I have attended and all the men

of eminence and goodness whom I have heard, and with whom I have associated.

My services, too, I trust, have not been unuseful to the great cause in

which they have been put forth. But I am tired of this life, and long to be

back again among the Chinese. My health is thoroughly re-established, and

every Chinese book on which I happen to cast my eye seems to put forth

characters of reproach and to tell me that I am not where I ought to be.'

London, Feb. 9, 1848.

'The principal engagement of

to-day was a private audience, first of Prince Albert, and secondly of the

Queen, along with the Chinese lads. I knew nothing of it till a letter came

from Lord Morpeth, saying that if I would be at the Palace at three o'clock

to-day he would be there to conduct me to the presence. Our audience was

very pleasant and courteous on the part of the Queen, and His Royal

Highness. He is a fine, handsome, gentlemanly-looking man, and she is a

sweet, quiet little body. She was dressed simply and unpretendingly. Her eye

is fine and rolling, and a frequent smile, showing her two front teeth,

makes you half forget you are before Majesty, though there is a very

powerful dignity about all her bearing. Our conversation was all about China

and the lads. The boys were much taken by surprise, having been expecting to

see a person gorgeously dressed, with a crown and all the other

paraphernalia of royalty. The interview will give the injunction of Peter a

heartiness to my mind; and for the words "Honour the King " I shall be

inclined to substitute "Love the Queen."'

DR. JAMES LEGGE.

From the portrait by George Richmond.

Later in the spring Dr Legge

and his family sailed again for Hong Kong. One day, shortly after leaving

Singapore, the cry of 'fire' rang through the ship. Smoke poured from the

hold; instantly the pumps were manned, the men passengers put under Dr

Legge's direction. He marshalled them in a line to convey buckets to and

fro. The steward had gone down into the spirit hold with a candle, which had

upset and set fire to a quantity of straw. In trying to stamp it out he

forgot to turn off the tap of the spirit cask, and thus the flames spread

rapidly.

After hard work, the combined

efforts of crew and passengers succeeded in getting the fire under, and they

reached Hong Kong without further mishap.

The prospect of war at this

time drew forth the following sentence in a letter.

'We ask our friends' writes

Dr Legge, 'to join with us in prayer to the Governor among the nations, that

he will avert the catastrophe of war. Wonderfully did he overrule the events

of the last war, to present a great and effectual door for the preaching of

his glorious gospel. Let its "still small voice" but continue to be heard by

the Chinese for a few years, and it will open all their country more

effectually to the rest of the world, than could be done by the thunder of

all the cannon in the British armies.'

A little daughter Annie, born

in England the year before, died a few months later, to the great grief of

her parents. Towards the end of September Dr Legge writes:—'This mail will

carry tidings of sorrow and death into fifty families, I suppose, in

Britain. There has been raging one of the most furious typhoons by which

this coast has been visited for many years. Houses were blown down and

unroofed, and many vessels dismasted or sunk. Not fewer than a thousand

Chinese must have perished in the Canton river alone, and one boat which was

cruising about this island with a company of invalid policemen, went down,

only six out of twenty-eight escaping. Among these drowned was a very

respectable man, a police inspector, converted, I hope, through my

instrumentality. He had his only son with him, a fine lad of eighteen. How

desolate is his widow. You will imagine what were my wife's feelings during

all this storm when I tell you that she was alone, with reason to believe

that I was exposed in a frail barque to its fury. On Wednesday evening I

embarked on a passage boat for Canton, and had got only about twenty-five

miles when we saw the typhoon coming. Providentially there was a small

harbour near, into which we put, and there we remained for thirty hours. It

was Monday evening before my wife heard of our safety. Had not the wind

failed us soon after our setting out, we must have been carried far beyond

our shelter. The fury of the tempest was inconceivable.

'Our hearts have been cheered

by tokens of God's blessing on our mission. Last Saturday fifteen

individuals made application to me for baptism. Five of them were boys in

the school, three of them evidently most deeply impressed by the truth. They

have been long revolving the step they have taken, for more indeed than

three years. Their decision opens a wide prospect of usefulness to me in the

Seminary. I shall now have a succession of faithful disciples under my care

to train for the ministry.

'Thus amid our desolation in

the loss of Annie we have been cheered.'

Some months later he

writes:—'I anticipate baptising two more of our boys next Sabbath, and with

them a man of thirty-six, a scholar from a considerable distance, who has

been residing here for between two and three months to be instructed in

Christianity. His case is one of much interest. The two boys are from the

first class and of very good abilities. In a year or two they will be quite

fit for enrolment as theological students. Thus I am more and more

encouraged to prosecute my plans to rear up a native ministry. Two other

boys have made a formal application for baptism. We are in no hurry to

baptise our candidates. They are well instructed and they give us all the

evidence we can expect of their sincerity. Kim-Lin and A-Sow are going on

very well. They are both labouring away at Euclid.'

In this place comes in a

letter addressed to his friends of the Committee of the Religious Tract

Society. Dr Legge writes:—

'In the early part of this

month I paid a visit, with some friends, to Tae-Pang, a walled town upon the

coast, about thirty miles to the north from Hong Kong. Walking through one

of the streets, I met an old man, between seventy and eighty, with whom I

entered into conversation, presenting him with a copy of the "Ten

Commandments," in the form of a sheet tract "These," said he, "I know; they

are the Commandments of Jesus. Two years ago I met with a book about the

doctrines of Jesus, and now I worship Him." You will conceive how my heart

was lifted up on finding that your silent messengers had thus prepared the

way of the missionary. "Who was Jesus?" and "Why do you worship Him?" were

questions put to the old man. "Jesus," he replied, "was the Son of God, and

He came into the world to be the Saviour. His work was to save men from

their sins; and I know that I am a great sinner. In the night-time, at the

first and third watch, I get up and pray to Jesus to have mercy upon me." I

endeavoured to improve my brief interview with him to the best advantage,

and when I am able to revisit the town will seek the old man out. His

appointed time upon earth must be drawing near its close, but may we not

hope that he will have cause to be thankful for the Tract Society throughout

eternity?'

The Doctor writes again to

the Society :—

'There came a man of

education to Hong Kong, about the middle of March, from a distance of a

hundred and fifty miles, and introducing himself to our colporteur. A-Sum,

requested to be instructed in the Christian doctrine. The way in which he

states he was brought here was this. An acquaintance came from his town last

year to Hong Kong, with a cargo of mats to sell, and while he was here

received a tract from A-Sum, which he handed to our friend on his return

home. This produced a considerable impression on his mind, which was much

increased by conversations in the beginning of this year with another

acquaintance, the manager of a rope-walk in this settlement, whom A-Sum and

myself have often visited. This man having gone home in January to see his

family, talked often among his friends of the gospel of Jesus, which had

been pressed on his acceptance. Our friend was prepared to be interested by

such a topic, and when the ropemaker returned to Hong Kong last month, he

came with him. Since he has been here he has read and heard much of the

Scriptures, and has recently formally applied for baptism. Being a scholar,

his progress in knowledge has been rapid. When told that by embracing

Christianity he would be brought to poverty, and that we could not do

anything for him in a worldly point of view, he replied that the Bible told

him that God is supreme, the Creator and the Sustainer of all men; and he is

ready, without fear, to cast himself on God.'

Another example of the

gracious influences that are at work in places where no missionary has ever

lifted up the voice of mercy came under the notice of Dr Legge whilst on a

journey of some distance into the interior. In the crowded street of a small

town he was accosted by a venerable-looking old man, whose snowy head

bespoke respect for him, in these terms:—'Pray, sir, are you a worshipper of

Jesus'? Being answered in the affirmative, he rejoined, with evident

pleasure, 'So am I; I pray to Him every morning and evening.' Dr Legge was

surprised to hear such a declaration in a place where, as far as he knew, no

missionary had ever been before, and questioned the man further as to who

Jesus was, and how he had come to know Him. He found that the old man

understood the outline of Gospel truth, which he had learned from a copy of

the Gospel of Luke, that by some means had come into his hands. We suppose

that he had overheard the doctor speaking to passers-by of the Gospel, and

had recognised this stranger's doctrine as that which he had found, in some

measure at least, precious to his soul.

In a letter of this period to

the London Missionary Society occurs another reference to A-Sow which is of

interest:—

'I am quite as frequently

cheered by evidences that the truth is among us, working both powerfully and

beautifully. As an instance of this I may refer to a simple but affecting

occurrence at a Bible class of the men members about three months ago. I had

been speaking on Matt, xviii. 19, "If two of you shall agree on earth,"

etc., when A-Sum, one of our oldest members rose up and said that he had

something which he wished to say to myself and his brethren.

"You all know my son-in-law,

A-Sow. Formerly he was one of us, but we had to expel him from the church.

Of the life which he has been living for several years I need not now speak.

He has been very bad, and he was as hardened as he was dissipated, and

repulsed me when I tried to advise him. Lately he was taken ill, and

thinking his heart might be softened, I ventured to speak to him about his

soul. He heard me quietly, and to-day he rose and came to this place of

worship. It is the first time he has been in God's house for years. Far as

he has gone astray, and deeply as he has sinned, perhaps God will have mercy

upon him yet. I feel it is in my heart to ask you all to pray with me that

he may be brought back to the fold. What you said, sir, about the verse 'If

two of you shall agree on earth as touching anything that they shall ask it

shall be done for them of My Father which is in heaven' has so moved me that

I could not but give expression to my feelings."

'The tearful eyes and

quivering voice with which this was spoken by my old friend, and the way in

which it was responded to by the others, made me feel that indeed I was

among Christian brethren, and that the Gospel operates upon the Chinese to

soften the soul and to intensify and sanctify the relative afflictions just

as it does upon Englishmen. May it be done for the backslider as we asked.'

'I have entered this month

(May 1849) into a new and important relation. I was asked to undertake the

duties of a pastor to the English congregation of Union Church. I replied

that I would do so, but could only preach once on Sunday, as I had to preach

in the evening in Chinese, and besides, could not accomplish two sermons a

week with all my other duties. The step is an important one. It places me in

a new position which will have its difficulties and advantages.'

A correspondent writes:—

'One of the most romantic

incidents which associates itself with Dr Legge's life is connected with the

career of a young Scotsman who came up to London as a journeyman printer. He

was from the same county of Aberdeen.

'Mr Alexander Wylie had

connected himself with Albany Congregational Church, near Regent's Park,

where a Scotsman was pastor.

'Something had put into the

heart of the young printer that he was called to be a missionary. He was

already a Sunday-school teacher. One day he was, according to custom, poring

over the treasures of an old book-stall, and came upon one of the Jesuit

Latin-Chinese grammars. Here was his opportunity. With dogged Scots

perseverance he mastered Latin that he might learn Chinese. He had made some

progress, and China seems always to have been in his mind as his final

destination.

'About this time Dr Legge

visited England, and Wylie, hearing this, entered into communication with

him. Dr Legge saw there was true grit in the man, and encouraged him, giving

him such aid as was in his power to give.

'In due time he offered

himself to the London Missionary Society, and for many years superintended

the Society's printing press at Shanghai. When this was given up he offered

himself to the British and Foreign Bible Society, and was accepted as that

Society's agent for China. All the time, however, he was applying himself

with more and more zeal to the acquirement of the language in its higher

departments. His influence as agent of the Bible Society, and as a helper in

the work of the Religious Tract Society became more and more apparent. He

was a very distinguished Chinese scholar, and had a world-wide fame among

Orientalists.

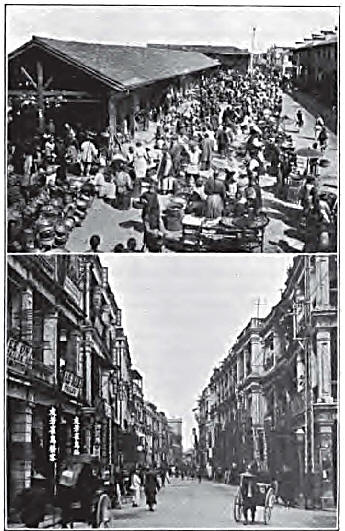

I. MARKET PLACE, EUROPEAN QUARTER, SHANGHAI.

2. STREET IN HONG KONG.

'Dr Legge's estimate of the

man and scholar may be judged from the fact that he remarked to the writer,

that in some branches of Chinese scholarship he regarded Mr Wylie as his

superior. As an old man, he returned to England nearly blind from the

excessive study of a language whose characters are so trying to all but the

best of eyes.

'After the Philadelphia

Exhibition, Mr Wylie called on me and stated that he desired to place, where

it would be valued, the remarkable collection of Chinese Christian

literature which he had collected and sent to Philadelphia. He asked my

opinion as to whether it should go to the British Museum, or to Oxford for

the Bodleian. The fact that Dr Legge was at Oxford decided the matter, and

two large cases of literature are now safely placed in the famous library.

Dr Legge engaged to make a classified catalogue of the whole, and he

rejoiced to have this collection where he hoped it might prove to be very

valuable as the years went on.'

A friend who had known Dr

Legge at Hong Kong, writes:—

'As to the dear Professor.

What can I say? As often as I think of him, and it is not seldom, so often

does my heart go out towards him in ever increasing love and gratitude. I

sometimes think that I should never have been in my present condition of

useful work, but for his fatherly love to me 42 years ago. I was then a

young man in Hong Kong, surrounded by gay companions, and beset by unlimited

temptations, specially peculiar to youth. This the Doctor knew, and no

father could have been more kind to his own son than he was to me.

"Think of my house as your

home in any time of trouble or temptation," said he. Yes, his was a loyal

spirit, which must have been "greatly beloved " by the All-Father. It is men

like him who make England strong, able to govern and guide the weaker

nations, rather than army or navy. The one trains the physical to overcome

the physical foe, but the sweet Professor ever sought to train the

spiritual, the real man, that he might overcome spiritual foes, and so reign

and govern for ever, and I have yet to learn that a man so helped, makes, if

need be, a less better soldier against his nation's enemies.

'Dr Legge preached from

personal experience, the ever present power of Christ to help in time of

temptation. My faith was much strengthened by such teaching, and often

before leaving the private house to go down to the day's work and

besetments, I would stand on the top of the stone steps and go no further

until I had realised the Divine presence. Then I sang on my way, ready for

whatever might be awaiting me.

'The evening tea-meetings,

specially for the army and navy, were of such delight to the doctor, and

under the blessed influence of his words, and the singing of some simple

hymn, I have seen great bearded men weeping as women weep, none the less

better soldiers and sailors for that.

'I need scarcely say, that

such a man was loved and trusted by all who knew him. More than once in the

evening time, when feeling lonely and sad, or under the stress of

temptation, I have turned towards the missionary's house as a storm-tossed

ship is turned towards a safe harbour. But I am deeply conscious that I do

not possess power of language to speak sufficiently of all the good I

received from that sweet, pure life.' |