|

AN old tradition relates

that Christianity had not long been

established over the Roman Empire

when one day a youth, weary

and footsore, entered one of the

gates of the Imperial City.

He came from a land in the far north which

few had heard of, and he had long travelled "per

mare et per terras" in his desire to study

the truths of faith by the tombs of the Apostles.

How long Ninian remained in Rome is not

stated; however, by command of the Pope,

he eventually retraced his steps home,

preached the gospel to his fellow-countrymen,

and founded the church of Galloway,

about two hundred years before St. Augustine landed in England.

Scotland, however, was too far

away and the difficulties

of travelling too great for

many

to follow in Ninian 's footsteps,

and so

the clergy was trained, not in Rome,

nor on the Continent, but in the

local monastic schools, which in Scotland, as elsewhere, were then the

homes of

learning and the nurseries of science. After

the monastic schools came the

universities, and St. Andrews and Glasgow

and Aberdeen became

the great

centres of intellectual work. It was only after the religious troubles

of the sixteenth century that the project of instituting a Scots college

in Rome was

formed.

The

ancient

monastery of St. James at Ratisbon,

founded by Marianus Scotus in 1068, had long

since fallen into a state of decay,

and so had the seminary which Abbot

Fleming had instituted in connection

with the old abbey. In 1576 another Scotch college was founded at

Tournay, not to speak of the one in Paris which

owed its existence

to Cardinal Beaton.

As far as Rome was concerned,

there had been a national church dedicated to St. Andrew, and a hospice

for the relief of Scotch pilgrims, long before the Reformation. The

modern church of S. Andrea delle Fratte occupies and marks the spot

where the devout people from beyond the Tweed found a welcome when they

came to visit the holy places at

Rome. It was Clement VIII. who, by a bull

dated December 5, 1600, gave the Scottish Catholics a national college.

Its site, very confined and

unsuitable, was in the Via del Tritone, near the

church of Our Lady of Constantinople. In

1604 it was

transferred to the Via delle Quattro Fontane, opposite to the present

Barberini palace, where it has remained ever since.

The history of this institution

has been given by Mgr. Robert Fraser, the present rector, in an

illustrated article published in the

March number of "St. Peter's Magazine" for

1899. It is remarkably uneventful as far as general interests are

concerned. More

interesting, perhaps, to the reader is another

incident in the history of Scottish-Roman relations, concerning the

prominent place gained by a Scottish gentleman as an archaeological

explorer of the Campagna.

The name of Gavin Hamilton was not

new in Rome. I have found in the records of the sixteenth century an

obligation signed December

3, 1554, by the Reverend Doctor Gavin Hamilton, abbot

of Kylwyning and coadjutor to the see of St.

Andrews in the

kingdom of Scotland, viz., a receipt for the

sum of three

thousand scudi of gold which he had borrowed from the bank of Andrea

Cenami in Paris. For the guarantee of which

sum he deposits

the papal brief of nomination to the coadjutorship of St. Andrews, and

offers the signature of three sponsors. Gavin Matreson, a priest of St.

Andrews, D. Bonard, canon of Dingwall, and Andrew Grayme, a priest of

Brechin. [State Archives, in the Cainpo Marzio, vol. 6166, p. 475.]

His namesake, the painter

and explorer of

the Campagna, was born at Lanark towards the middle of the eighteenth

century, of an ancient and

respected family, the Hamiltons of Murdieston. Having

displayed from an early age a marked

predilection for the fine arts,

and not finding

opportunities to gratify such a taste in his native land, he moved to

Rome, where he soon acquired great renown, and where he passed the rest

of his life, revisiting Scotland only at long intervals

and for very short

periods. [See Lord Fitzuiaurice's article in the Academy, quoted by A.

H. Smith, Catalogue of ... Marbles at Lansdowne House," p. 7.]

I shall not follow his career as

an artist, nor shall I describe his celebrated paintings in the Casino

of the Villa Borghese, representing scenes from the Iliad. His

partiality as an artist for Homeric

subjects is shown not only by the great

frescoes just mentioned, but also by smaller pictures, representing such

scenes as Achilles standing over the dead body of Patroclus, Achilles

dismissing Briseis, and

Achilles dragging the body of Hector, which have

passed into the collections of the Duke of Hamilton, of Lord Hopetoun,

and of the Duke of Bedford. [These subjects have been engraved by Cunego,

Morghen, and others.]

Gavin Hamilton attracts us more as

an archaeological explorer of the Roman Campagna, as an indefatigable

excavator, as a man of enormous activity crowned

by extraordinary

success. He was not working alone, but as a

member of a

company, formed, I am sorry to say, more for a lucrative than for a

scientific purpose. There were three of them, associated from 1769 or

1770: James

Byres, architect; Gavin Hamilton, painter; and Thomas Jenkins, banker.

The place of Byres was afterwards taken by Robert Fagan, English consul

at Rome. In volume i. of the "Townley Marbles" the Villa of Hadrian is

indicated as their principal field of operation; but this is not

precisely true. There is no doubt that the discoveries they

made in the

Pantanello, near the gates of Hadrian's Villa, count among the most

successful of the century; but they

had the same if not a better chance at Ostia,

Porto, Ardea, Marino, Civita Lavinia, Torre Colombara, Campo Jemini,

Cornazzano, Monte Cagnolo, Roma Vecchia, Gabii, Subiaco, Arcinazzo, etc.

The

documents concerning these excavations, unedited for the greater part,

will be found in volume iv. of my "Storia degli Scavi di Roma." The

second member of the company, James Byres, architect, was the special

correspondent and

purveyor of Charles Townley, as Hamilton was of

William Fitzmaurice, second Earl of Shelburne, first Marquis of

Lansdowne, and founder of the Lansdowne Museum of Statuary. Byres,

besides working in the interest of the company, carried on a trade of

his own, especially in rare books and drawings and in smaller and

precious objects, among which were the "Mystic Cista" of Palestrina of

the Townley Collection (found 1786), the bronze patera of Antium (found

1782), and the golden fibula of Palestrina,

now in the British

Museum, etc. Byres returned to his native land in 1790,

and died at Tonly,

Aberdeenshire, in 1817, at the age of eighty-five.

"Thomas Jenkins first visited Rome

as an artist, but having amassed a considerable fortune by favor of

Clement XIV. (Ganganelli) became the English banker. He was driven from

Rome by the French, who confiscated all they could find of his property.

Having

escaped their fury, he died at

Yarmouth immediately on his landing after a

storm at sea, in 1798. For an account of his extensive dealings in

antiquities (especially the purchase

and dispersion of the Montalto-Negroni

collection) see Michaelis, Anc. Marbles,' p. 75."

I must say that the dealings of

Hamilton and his associates with the government of the land whose

hospitality they enjoyed were not always fair

and above board.

Payne Knight, giving evidence before the Select Committee of the House

of Commons, on the Elgin Marbles, in 1793, distinctly affirms that

some of the

marbles could only be removed from Rome by bribing the Pope's officials,

while others were "smuggled" or "clandestinely brought away."

In a letter addressed by Hamilton

to Lord

Shelburne on July 16, 1772, we

find the following passage: "In the meanwhile I give

your Lordship the agreeable news that the Cincinnatus (discovered at the

Pantanello in 1769) is now

casing up for Shelburne House, as the Pope has

declined the purchase at the price of

.500, which I

demanded, and has accepted of two other singular figures, . . . which I

have given them at their own price, being highly necessary to keep

Visconti and

his companion the sculptor my friends. Your Lordship

may remember I mentioned in a former letter that I had one other curious

piece of sculpture which I could not divulge. I must, therefore,

beg leave to

reserve this secret to be brought to light in another letter,

when I hope I

shall be able to say it is out of the Pope's dominions.

As to the Antinous,

I am afraid I shall be obliged to smuggle it, as I can never hope for a

license."

And in a second letter, dated

August 6, he adds: "Since my last I have taken the resolution to send

off the head of Antinous in the character of Bacchus without a license.

The

under-antiquarian alone is in the secret, to whom I have made an

additional present, and hope everything will go well."

His luck as a discoverer of

antiques was simply marvellous, and many of his reports sound like fairy

tales. The

year 1769 is the date of the excavations at the Pantanello, the product

of which was mostly purchased by Lord Shelburne for the gallery at

Lansdowne

House. Hamilton himself wrote an account of the proceedings to Townley,

a synopsis of which is given by Dallaway (" Anecdotes of the Arts in

England," London, 1800, p. 364). The

place had already been explored

by a local

landowner, Signer Lolli. Hamilton and

his associates in the antiquarian speculation

"employed some

laborers to re-investigate this spot. They began at a

passage to an old drain cut in the rock, by means of which they could

lower the waters of the Pantanello. After having worked some weeks by

lamplight, and up to the knees in stinking mud full of toads, serpents,

and other vermin, a few objects were found . . . but . . . Lolli had

already carried away the more valuable remains. The explorers

fortunately met

with one of Lolli's workmen, by whom they were

directed to a new spot."

"It is difficult to account,"

Hamilton writes to Townley, "for the contents of this place, which

consisted of a vast number

of trees, cut down

and thrown into this hole, probably from

despite, as having been part of some

sacred grove, intermixed with statues, etc.,

all of which have shared the same fate. More than fifty-seven pieces of

sculpture were discovered in a greater .or less degree of preservation."

[Catalogue given by Agostino Penna, in his Viaggio pittorico della Villa

Adriana, Roma, 1833. The exploration of the Pantanello lasted from 1769

to 1772. Piranesi gives another excellent account in the description of

his plan of Hadrian's Villa.]

The search at Torre Colombara,

near the ninth mile-stone of the Appian

Way, began in the

autumn of

1771. Two spots were chosen about half a mile apart: one supposed to

have been a temple of Domitian, the other a villa of Gallienus. Hamilton

was struck by the number

of duplicate statues found in these excavations, one

set being greatly inferior to the other in workmanship and finish, as if

there had been an array of originals and one of replicas. The statues

lay dispersed all over the place, as if thrown aside from ignorance of

their value, or from a religious prejudice.

Some were lying

only a few inches below the surface of the field, and bore marks of the

injuries inflicted upon them by the ploughman.

First to

come to light was

the Marcus

Aurelius, larger than life, now at Shelburne House.

The Meleager, the

jewel of the same collection, and one of the finest statues in England,

was next found; and also the so-called "Paris Equestris," sold by

Jenkins to Smith Barry, Esq. The

same gentleman purchased at a later period a

draped Venus, to which was given the

name of Victrix. In fact, most of the leading

European collections have their share of the finds of Torre Colombara.

The Museo Pio Clementino secured the celebrated Discobolus, now in the

Sala della Biga, n. 615, the colossal bust of Serapis, now in the

Rotonda, n.549, and

some smaller objects; [Compare Helbig's Guide, vol. i.

p. 236, n. 331, and p. 217, n. 304.] Mr. Coch, of Moscow, a sitting Faun

and an Apollinean torso of exquisite grace; Dr. Corbett, a

Venus; Lord

Lansdowne, an Amazon; and so forth.

The crowning point of Hamilton's

career must be found in the search he

made in the spring

of 1792 among the ruins of Gabii. Ciampini, Fabretti, Bianchini,

and other

explorers of Latium had

already identified the site of this antique city, the

Oxford of prehistoric times, with that of Castiglione on the southeast

side of the lake of the same name. Many valuable or curious remains had

come accidentally to light in tilling the land, especially in the

vicinity of the temple of Juno, which marks the centre of the Roman

municipium, and of the church of S. Primitive, which

marks the centre

of Christian Gabii. These discoveries having become more and more

frequent in the time of Prince Marc' Antonio Borghese the elder, he

readily accepted Hamilton's application to

make a regular

search.

The work began in March, 1792,

and lasted

a comparatively short time; yet the results were such that Prince Marc'

Antonio was obliged to add a new wing to his

museum in the

Villa Pinciana, to exhibit the Gabine marbles, the summary description

of which by Ennio Quirino Visconti (Rome, Fulgoni, 1797) forms a bulky

volume of one hundred and eighty-one pages and fifty-nine plates.

Hamilton had laid bare two important edifices: the temple of Juno, with

its sacred enclosure and its hemicycle opening on the Via Praenestina,

and the Forum

and the Curia of the Roman Gabii. Here he found

eleven statues or important pieces of statues of mythological subjects;

twentyfour statues or busts or heads of historical personages, including

Alexander the Great, Germanicus, Onaeus Domitius Corbulo, the greatest

Roman general of the time of Nero, Claudius, Geta, Plautilla, etc.;

seven statues of local worthies, seven pedestals with eulogistic

inscriptions, besides columns, mosaic pavements, architectural

fragments, coins, pottery, glassware,

and bronzes.

The end of the Borghese Museum is

well known. The most valuable marbles, those from Gabii included, were

removed to Paris by the first Napoleon, for which an indemnity of

fifteen millions of francs was promised to Prince Borghese.

The greater part

of this sum

remained unpaid at the fall of the French Empire,

and is

still unpaid. England, as usual, had

her share in the spoils from Gabii. Visconti

informs us that a beautiful polychrome mosaic floor, discovered among

the ruins of a villa, at a certain

distance from the temple of Juno,

was purchased by "my Lord Harvey, count of Bristol,"

and removed to his

country seat in Somersetshire. The year 1717 marks the arrival of the

"last of the Stuarts" in the States of the Church. Under the name of the

Chevalier de St. Georges, James III., son of James II. and of Mary

Beatrice of Modena, sought the hospitality of Pope Clement XI., Albani,

in the beautiful ducal castle at Urbino.

The Chevalier de

St. Georges was not altogether unknown to the Romans. Many among the

living remembered the celebration made by Cardinal Howard on the

announcement of his birth in 1688,

when an ox stuffed with game was roasted in

one of the public squares, and served to the populace. A rare engraving

by Arnold van Vesterhout represents this event. ["Stampa di un bue

arrostito intero, ripieno di diversi animali, comestibili in publica

piazza, da distribuirsi al volgo, in occassione delle allegrezze

celebrate in Roma dal Card. Howard, per la nascita del principe Giacomo."

Roma, 1688.]

The marriage of James III. with

Mary Clementina, granddaughter of the great John III., Sobieski, of

Poland, arranged by

Clement XI. in 1718, was attended with considerable

difficulties. While

crossing the Austrian territory, she was detained in

one of the Tyrolean castles by order of Charles VI., Emperor of Austria.

She

succeeded, however, in eluding the vigilance of the keepers, and,

disguised in a young man's attire, made good her escape. When she

reached Rome in the spring of 1719, the Pope bade her take up her

quarters in the monastery of the Ursulines, in the Via Vittoria. This

monastery still exists, although transformed into a royal

Academy of Music.

The marriage was celebrated in the village of Montefiascone, on the

Lake of

Bolsena, where the royal couple spent their honeymoon. There is a scarce

engraving of the wedding ceremony, by Antonio Frix, from a sketch by

Agostino Masucci, bearing the title: "Funzione fatta per lo sposalizio

del re Giacomo

con la principessa Clem. Sobieski."

In Rome they established their

residence in the Palazzo Muti-Savorelli, now Balestra, at the north end

of the Piazza

de' Santi Apostoli, the rent being

paid by the Pope. The Pope also offered

them an annual

subsidy of fifteen thousand dollars, besides a wedding present of a

hundred thousand. The old baronial manor of the Savelli at Albano was

put at their disposal for a summer

residence. [After the death of his parents and

brother the Savelli manor passed into the hands of Cardinal York. An

English visitor who saw it about 1800 gives the following details:

"Cardinal Stuart . . .has a palace in Albano, which was given him by the

Pope. He never resides there, but successively lent it to the Spanish

ambassador, and to the princesses Adelaide and Victoire, aunts of the

unfortunate Lewis XVI. . . . This palace ... is furnished in the

plainest manner, and in one of the principal rooms are maps of London,

Rome, and Paris, as also one of Great Britain, on which is traced the

flight of the late Pretender." See Description of Latium, p. 69, London,

1805.]

The birth of their first son,

which took place December 31, 1720, gave occasion for great

manifestations of loyalty. The event was announced by a royal salute

from the guns of the Castle of St. Angelo,

and by the joyous

ringing of some two thousand bells. N.

544 of the "Diario

di Roma" contains an account of the baptism of the infant prince under

the name of Charles Edward. The sponsors were Cardinal Gualtieri for

England, Cardinal Imperiali for Ireland,

and Cardinal

Sacripante for Scotland. Clement XL said mass in the chapel of the

English college, and

gave, as presents, a Chinese object valued at four

thousand dollars and

a cheque amounting to ten thousand.

Their second son, Henry Benedict,

Duke of York, was born in 1725 and baptized by Pope Benedict XIII. in

the chapel of the Muti palace. Among the presents received on this

occasion were the "Fascie benedette." "Fascie" in Italian

means a long

band of

strong white linen, with which newborn infants are tightly swathed

during the first months of their life. However ungentle this practice

may seem, it is kept up in Italy even in our

own days, as the

people believe they impart more

firmness of limb to their children by swathing

them in

this manner.

The habit of the papal court of

presenting these fascie to the eldest born of a royal house dates as far

back as Clement VII., Aldobrandini. This

Pope gave them,

for the first time, in 1601, to Henry IV. of France, whose second wife,

Maria de' Medici, had given birth to the dauphin, the future Louis XIII.

The fascie

were intrusted to a special ambassador, Maffeo Barberini,

who afterwards

became Pope Urban

VIII.

The presentation of the baby bands

to James

III. and his Queen Clementina is fully described in no.

1200 of the "Diario

di Roma."

It took place on April 5, 1725, the prelate selected as envoy

extraordinary being Monsignor Merlini Paolucci, Archbishop of Imola.

The bands

and other articles of a rich layette were enclosed in two boxes, lined

with crimson velvet embroidered in solid gold. There were bands also

ornamented with gold embroidery, and

others of the finest Holland linen trimmed

with exquisite lace. The gift to the infant prince was valued at

8000 scudi.

From the same invaluable source,

the "Diario di Roma" (n. 2729), we gather many particulars about the

death of Queen Clementina, which took place on January 18, 1735, and

about her interment in St. Peter's. The theatres were closed, much to

the annoyance of the managers and

the public, as it was carnival time; also the

illuminations and fireworks prepared in honor of the newly elected

Cardinal Spinelli, Archbishop of Naples, were given up.

The funeral

ceremonies began in the parish church of SS. Apostoli, where the body of

the Queen was

exposed on a catafalque, of which

we have an etching

by Baldassarre Gabuggiani.

The funeral cavalcade from the

parish church to the Vatican, of which there is a print

by Rocco Pozzi,

was attended by the college of cardinals in their violet or mourning

robes. On the preceding day the governor of the city, Monsignor Corio,

had issued the following proclamation:

"On the occasion of the

transferment of the mortal remains of

Her Majesty

Clementina Britannic Queen, which will take place to-morrow with due

and

customary solemnity, and with the view of removing all obstacles which

might interfere with the orderly progress of the pageant from the church

of SS. Apostoli to St. Peter's, we, Marcellino Corio, Governor of Rome

and its district . . . order, command, and bring to notice to all

concerned, of whatever sex or condition of life, not to trespass or

intrude over the line of the procession with their coaches, carriages,

or wagons, under the penalty of the loss of the horses besides other

punishments for the owners of the said coaches, carriages,

and wagons, while

the coachmen

or drivers shall be stretched three times on the rack

then and

there without trial or appeal. Given in Rome from our residence this

day, January 21, 1735."

(Signed) Marcellino Corio,

Governor; Bartolomeo

Zannettini, Notary.

The college of the Propaganda

commemorated the event

by holding an assembly in which

the virtues of Mary Clementina were celebrated and sung in twenty

different languages, including the Malabaric, the Chaldsean, the

Tartaric, and the Georgian. Two monuments were raised to her: one in SS.

Apostoli, one in St. Peter's. The

first consists of an urn of "verde antico,"

and a tablet of "rosso," containing the celebrated epigram:

Hie Clementinas remanent prsecordia:

nam Cor

caelestis fecit, ne superesset, amor.

I have a suspicion that the

distich was written by Giulio Cesare Cordara, S. J., a great admirer of

the late princess. The same learned man wrote a pastoral drama, called

"La Morte di Nice" (Nike's Death), printed at Genoa, 1755, and

translated into Latin by Giuseppe Vairani.

The body was laid

to rest in St. Peter's, in a recess above the door leading to the

dome (Porta della

Cupola). The

tomb, designed

by Filippo Barigioni, cut in

marble by Pietro Bracci, with a mosaic medallion by Cristofori, was

unveiled on December

8, 1742. [Literature: Vita di Maria Clem., etc.,

Bologna, 1744; Parentalia Marios Clem. Magnce Brittannice reginaz, Romse,

1735; Solenni esequie di Maria Clem., etc., celebrate in Fano, Fano,

1735; Casabianca Francesco, Epicediumpro immaturofunere Marias Clem.,

Roinae, 1738; Il Cracas, n. 3960, 3322, 2990; Pistolesi, // Vaticano

descritto, vol. i. p. 257.]

It cost 18,000 scudi, taken from

the treasury of the chapter of St. Peter's.

It seems that the happiness of

Queen

Clementina's domestic life was occasionally affected by passing clouds.

After her death the king [See Francesco Cecconi, Roma antica e moderna,

1725, p. 669.] took even more interest in Roman patrician society.

In a book of records of Pier Leone

Ghezzi, now

belonging to the department of antiquities of the

British Museum,

I have found the account of a visit paid by the king

to Cardinal Passionei in his summer

residence at Camaldoli near Frascati, on

October 19, 1741. "The King of England," Ghezzi says, "was accompanied

by the Princess Borghese and

the Princess Pallavicini, alone, without any escort

of 'demoiselles d'honneur.''

Many interesting particulars about

the life of the pair in Rome,

related by contemporary daily papers, are now almost

forgotten. They

were very fond, for instance, of enjoying the popular

gathering called the Lago di Piazza Navona. This noble piazza, still

retaining the shape of the old Stadium of Domitian and Severus

Alexander, over the ruins of which it is built, used to be inundated

four or six times a year, during the hot summer months, by stopping the

outlet of the great fountain of Bernini, called the Fontana dei Quattro

Fiumi. Stands and balconies were erected around the edge of the lake;

windows

were decked with tapestries and flags; bands of music played, while the

coaches of the nobility would drive around where the water was shallow.

It was

customary with the owners of the palaces bordering on the piazza to send

invitations to their friends, and treat them with refreshments and

suppers.

The first mention I find of the

presence of James and Maria Clementina at this curious gathering dates

from Sunday, August

11, 1720. They were the guests of Cardinal Trojano

Acquaviva, who had built a stand in front of his church of S. Giacomo

degli Spagnuoli, hung with red damask

trimmed with bands of gold. Refreshments were

served, and

the royal guests took such pleasure in the spectacle

that twice again they appeared at that same balcony before the season

was over, on August

25 and September 1.

The young Prince Charles was

allowed to see the Lago for the first time in 1727, August 4.

The following

year, taking advantage of the absence of his mother, Charles amused

himself by throwing half-pennies into the water and watching the

struggles of the young beggars to secure a share of the meagre bounty, "cosa

di poca decenza per un

figlio di Re."

I find the last mention of their

presence in 1731, in the balcony of Cardinal Corsini, whose pastry-cooks

and butlers had been at work for three days and nights in preparing the

supper-tables. The Lago is thus described by de la Lande in his "Voyage

en Italic dans les Annees 1765 et 1766," v. p. Ill : "La grande quantite

d'eau, que donnent ces trois fontaines [of the Piazza Navona] procurent

en ete un

spectacle fort singulier, et fort divertissant. Tous les dimanches du

mois d'aout, apres les vepres, on ferme les issues des bassins. L'eau se

repand dans la place, qui est un

peu concave, en forme de coquille.

Dans 1lespace de

deux heures elle est inondee sur presque toute sa longueur, et il y a

vers le milieu deux ou trois pieds d'eau. On vient alors se promener en

carrosse tout autour de la place. Les chevaux marchent dans l'eau; et la

fraicheur s'en communique a ceux meme, qui sont dans la voiture. Les

fenetres de la place sont couvertes de spectateurs. On croirait voir une

naumachie

antique. J'ai vu le palais

du Cardinal

Santobono Caracciolo rempli ces jours la de la plus belle compagnie de

Rome. II faisoit lui-meme les honneurs de ses balcons par ses manieres

nobles, et engageantes, auxquelles il joignoit les refraichissemens les

plus fins. Autrefois on passoit la nuit a la place Navone. On y soupoit,

on y faisoit des concerts. Mais Clement XIII. a proscrit tous les

plaisirs. Des l'Ave Maria on commence

a desecher la place. II arrive quelque fois

des accidens a cette espece de spectacle. Des chevaux s'abattent, et si

l'on n'est pas tres-prompt a les degager, ils se noyent. C'est ce que

j'ai vu

arriver aux chevaux du prince Barberini en 1765. Mais quand on suit la

file avec moderation, l'on n'est gueres expose a cet inconvenient. L'eau

ne vient pas au dela des moyeux de petites roues dans 1'endroit ou les

carrosses se promenent."

In Sir Alexander Dick's "Travels

in Italy" (1736), printed in "Curiosities from a Scots Charta Chest,"

by the Hon.

Mrs. Atholl Forbes, there are many jottings about the Duke of York as a

boy of eleven: "The little young duke . . . was very grave

and behaved like a

little philosopher. I could not help thinking he

had some

resemblance to his great-grandfather Charles the First. . . . The Duke

of York . . . danced very genteelly," etc.

Charles Edward, after the death of

his father, lived in retirement under the

name of Count of

Albany, and, following the advice of France, married the Princess Louise

of Stolberg, his junior by thirty-two years. After they had spent some

time together in Tuscany, as guests of the Grand Duke Leopold, the

countess left the conjugal roof and established herself in Rome under

the guardianship of her brother-in-law, Cardinal York. We shall deal no

longer than is necessary with this lady; she died in Florence in 1824,

after many adventures, with which any one who has read the life of

Alfieri, the great Italian tragedian, must necessarily be acquainted.

Charles Edward

died in Florence on January 31, 1788. His

body was removed

to Frascati, the episcopal see of his brother, and a "recognitio

cadaveris" was performed before the

entombment in St. Peter's.

The body was found

clad in a royal robe, with the crown, sceptre, sword,

and royal

signet-ring; there were also the insignia of the knighthoods of which

the sovereign of Great Britain is the grand master de jure. The cardinal

did his best, to obtain a state funeral in Rome; but the Pope refused,

on the ground that Charles Edward had never been recognized as a king

by the Holy

See.

The Duke of York, younger son of

James III., was elected cardinal on July 3, 1747, while in his

twenty-second year. [Compare Life of Henry Benedict Stuart, Cardinal

Duke of York, by Bernhard W. Kelly, London, Washbourne, 1899: "A good

little work, which might have been much better had its author gone to

such accessible sources as von Reuinont's Grafin v. Albany, Mr. Lang's

Pickle the Spy, and above all James Browne's History of the Highlands.

The last, a great but neglected storehouse of Jacobite lore, contains

more than a score of letters by, to, or about the cardinal "

(Athenaeum).]

Officially he was called the

Cardinal Duke of York; but after the death of the elder brother he

proclaimed himself the legitimate sovereign of Great Britain and

Ireland, under the name of Henry IX. Within the walls of the Muti

palace, or of the episcopal residence at Frascati, he claimed the title

of Majesty, but among his colleagues of the sacred college he was simply

styled, "His Serene Highness Henry Benedict Mary Clement, Cardinal Duke

of York."

Such a profusion of

names was not

calculated to please his colleagues,

who more than once found a way of showing

their disapproval.

The friendship between Pope

Benedict XIV. and the young prince of the church

became rather

strained in 1752. It seems that the latter had taken an extraordinary

fancy for a certain Mgr. Lercari, his own "maestro di camera," while his

father could not tolerate his presence. Lercari's dismissal was asked

and

obtained; but the two friends continued to meet almost daily, or else to

communicate by letters. Annoyed at this state of things,

James III. applied

to the Pope for advice and help, with the result that young Lercari was

banished from Rome on the night of July 19.

The cardinal

resented the measure as a personal offence, and on the following night

he left the paternal home for Nocera. Benedict XIV. wrote several

letters pointing out how such an estrangement between father and son,

between Pope

and cardinal, would give satisfaction to their common

foes on the other side of the Channel. After five

months of brooding

the duke gave up

his resentment, and accepted Mgr. Millo as "maestro

di camera." The reconciliation, which took place on

December 16,

pleased the court and the people beyond measure, because father and son,

king and cardinal, had won the good graces of all classes of citizens by

their charities and

affable manners, so different from the dignified

gloom

characteristic of the Anglo-Saxon race abroad.

His nomination to the bishopric of

Frascati, July 13, 1761, is the next important event

we have to

chronicle, as it was the indirect cause of the destruction of one of the

noblest monuments

of the old Latin civilization. In the mean time there

are some curious particulars to be called to

mind in connection

with his residence at Frascati, the diocese of which he governed for

forty-three years. He loved this residence so dearly that whenever he

was called to Rome to attend a consistory or a "Cappella Pontificia,"

more than once he killed his carriage-horses in his haste to get back to

Frascati. His banqueting hall was always open to guests,

and very often

messengers were dispatched to Rome on the fastest ponies to secure the

delicacies of the season. The members of his household were all handsome

and imposing, their liveries superb.

The library of the local seminary contains

still a valuable set of English standard works, and the cathedral many

precious vessels, the gift of this generous man. It is a pity that we

should be compelled to bring home to him an act of wanton destruction,

for which I can find no apology. [There is a fine portrait of the

Cardinal by Pompeo Batoni in the National Portrait Gallery. Sins of the

Drunkard, a temperance tract by him, is read to the present day, I

believe, in every church of the diocese of Liverpool, twice a year.]

Visitors to the Eternal City

and

students of its history know how the beautiful Campagna is

bounded towards

the south by the Alban

Hills, the graceful outline of which culminates in a

peak 3130

feet high, which the ancients called Mons Albanus, and moderns call

Monte Cavo. On this peak, visible from Latium, Etruria, Sabina,

and Campania,

stood the venerable temple of

Jupiter Latialis, erected by Tarquinius Superbus as the meeting-place of

the forty-seven cities which formed the Latin confederation.

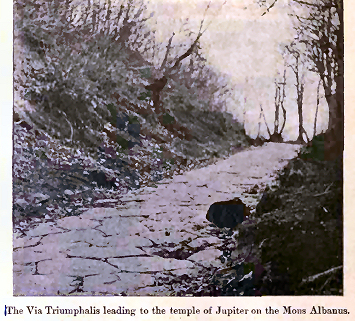

The temple was

reached by a paved road which branched off from the Via Appia at Ariccia,

and

crossing the great forest between the lakes of

Nemi and Albano,

reached the foot of the peak in the vicinity of Rocca di Papa.

The pavement of

this Via

Triumphalis, trodden by the feet of Q. Minutius Rufus, the conqueror of

Liguria, of M.

Claudius Marcellus, the conqueror of Syracuse, of

Julius Caesar, as dictator, etc., is in a marvellous state of

preservation; not so the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, which stood

at the summit of the road.

From a rare drawing of about 1650

in the Barberini library we

learn that the federal sanctuary stood, facing

the south, in the middle of a

platform enclosed and

supported by a substructure of great blocks of tufa.

Columns of white marble, or of giallo antico,

and marble blocks

from the cella of the god, inscribed with the "Fasti Feriarum Latinarum,"

lay scattered over the sacred area, in the neighborhood of which

statues, bas-reliefs, and votive offerings in bronze

and terracotta

were occasionally found. These remains were mercilessly destroyed in

1783 by

Cardinal York, to make

use of the materials for the rebuilding of the

utterly uninteresting church and

convent of the Passionist monks which he

dedicated to the Holy Trinity on October 1 of the same year. This act of

vandalism of the last of the Stuarts was justly denounced by the Roman

antiquaries, and we wonder why so great an admirer of ancient art as

Pius VI. did not interfere to prevent it.

The temple was one of the national

monuments of Italy, and no profaning hand should have been allowed to

remove a single one of its stones. It was not necessary to be a student

or a philosopher to appreciate the importance of the

place. "On the summit of Monte

Cavo," writes an English visitor contemporary with these events," it is

impossible not to experience sensations at once awful

and delightful;

the recollection of the important events which led the masters of the

world to offer up at this place their homage to the Deity is assisted by

the great quantity of laurel still growing here."

The same visitor

saw in the garden of the

convent "fragments of cornices of

good sculpture; and when we were on the hill the masons were employed in

making a shell for holy water out of part of an antique altar." How

often have I sat on one of the few blocks of stone left on the historic

peak to tell the tale of its past fortunes and glory, wondering at the

strange chain of events which prompted a scion of the savage Picts to

lay hands on the very temple in which thanks

had been offered

to the Deity for Roman victories and Roman conquests in the British

Isles!

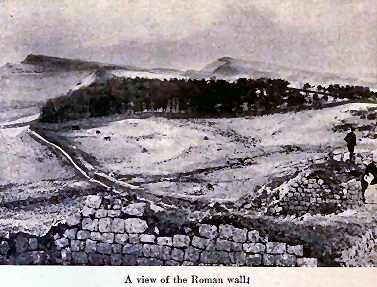

When the Romans were raising their

mighty ramparts to confine the Caledonian tribes within prescribed

boundaries, and cut them off, as it were, from the rest of mankind; when

Agricola was building his nineteen forts, A. D. 81, between the Forth

and the

Clyde; when

Lollius Urbicus completed this line of defence, A. D.

144, by the

addition of a rampart and

ditch between old Kirkpatrick and Borrowstoness; when

Hadrian raised his wall and his embankment, A. D. 120, between the Tyne

and the Solway, subsequently repaired

by Septimius

Severus, did they dream that the day would

come when one of

the Picts yonder would follow in their footsteps along the Via

Triumphalis, and wipe off from the face of the earth the temple of the

god to whom the conquering heroes had paid respect, and presented votive

offerings from the islands beyond the Channel?

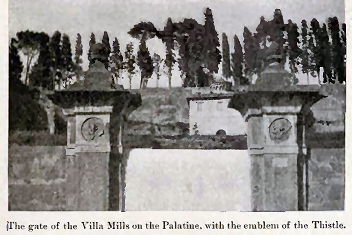

There is another and

more glaring

instance of this striking irony of fate to be found in Rome itself. The

palace

of Augustus on the Palatine Hill,

where the emperor lived for forty years, kept in repair as a place of

pilgrimage down to the fall of the Empire, this most august of Roman

historical relics, after having been plundered in 1775 of its contents

by the Frenchman Rancoureuil, fell in 1820 into the hands of Charles

Mills, Esq. This Scotch gentleman caused the Casino (built and painted

by Raffaellino dal Colle near and

above the house of Augustus) to be

reconstructed in the Tudor style with Gothic battlements, and raised two

Chinese pagodas, painted in crimson, over the exquisite bathrooms used

by the founder of the Empire. And for the branches of laurel and the

"corona civica," which in accordance with a decree of the Senate

ornamented the gates of the palace, Charles Mills substituted the

emblem of the

Thistle.

The death of Cardinal York, which

took place at ten p. m. of July 13, 1807,

was mourned by the

population of the diocese of Frascati as an irreparable loss. He had

been their good and generous pastor for half a century, he had been

cardinal for sixty years, he had been archpriest of St. Peter's for

fifty-six; in his long career he had

won the good graces of every one, and made no

enemies. The body was removed to Rome and exposed in the main hall of

the Palazzo della Cancelleria. The

funeral was celebrated on the following

Thursday, July 16, in the parish church of S.

Andrea della

Valle, in the presence of Pius VII. and the Sacred College.

The same evening

the coffin was removed to St. Peter's, and placed in the crypts, near

those of his father and brother. The three last representatives of a

valiant and noble race, whose faults had been atoned by long

misfortunes, were thus reunited and laid to rest under the mighty

dome of the

greatest temple ever raised for the worship of the true God.

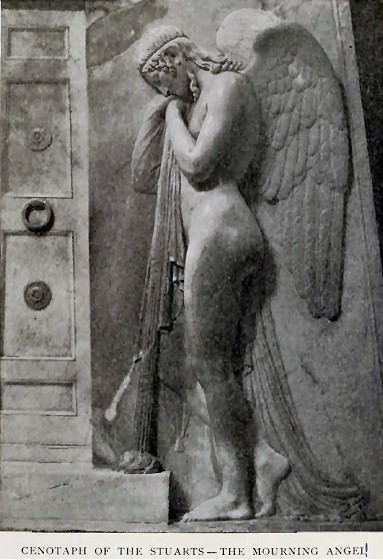

I need not dwell on the cenotaph

raised to their memory opposite that of Maria Clementina, nor on the

well known dedication REGIME STIRPIS STVARDIAE POSTREMIS! The Duke of

Sussex, sixth son of George III. and

brother of George IV. and William IV., who

contributed fifty guineas towards the erection of the memorial, was a

special admirer of the old cardinal, having been his neighbor for one

whole

summer on the hills of Tusculum

and Albano. [The Alban and Tusculan hills have always been in favor with

the English visitors to Rome since the eighteenth century, and there is

110 villa in that district which might not be associated with an

historical name. The Duke and Duchess of Gloucester lived some months in

the Villa Albani at Castel Gandolfo, and the Duke of Sussex passed a

whole summer at Grottaferrata, within the diocese of the last of the

Stuarts. Pius VI. gave a dinner to the duke in the farmhouse of la

Cecchignola, on the Via Ardeatina, where the venerable old Pontiff used

to go in the month of October, to amuse himself with the Paretajo. The

Paretajo consists of a set of very fine nets spread vertically from tree

to tree in a circular grove, in the centre of which flutter the decoy

birds. At the time of the great flights of migratory birds the catching

of one or two hundred of them in a single day is not a rare occurrence,

if the Paretajois skillfully put up.] Kelly says in connection with his

visits: "It is said on good

authority that one of the brothers of George IV. took

a journey to Frascati, to receive in 'orthodox fashion from the hands of

Henry IX. the healing touch which had

been denied to the rulers of his own dynasty,"

and that knowing the cardinal's pretence to a royal title, he, the son

of George III., had not hesitated to comply with his wish. English

describers of Rome are in the habit of quoting with relish the

well-known passage of Lord Mahon:" Beneath the unrivalled

dome of St.

Peter's lie mouldering the remains of what was once a brave

and gallant heart;

and a

stately monument from the chisel of Canova, and at the charge, I

believe, of the house of Hanover, [The monument was really erected at

the expense of Pius VII. ] has since risen to the memory of James III.,

Charles III., and Henry IX., kings of England,

names which an

Englishman can scarcely read without a smile or a sigh."

Lord Mahon could

have saved both his smiles and

his sighs if he had simply read with care the epitaph

engraved on the monument, which says: "To James III., son of James II.,

King of Great Britain, to Charles Edward, and Henry,

Dean of the Sacred

College, Sons of James III., the last of the Royal

House of Stuart."

Let us join, however, with Lord Mahon in the prayer which is heard so

often in Roman funeral services: Peace be with

them! REQUIESCANT

IN PACE! |