|

Chapter

VII.

"Auld Botany Ben was wont to jog

Thro' rotten slough and quagmire bog,

O'er brimful dykes and marshes dank,

Where Jack o' Lanterns play and prank,

To seek a cryptogameous store

Of moss and carex and fungus hoare,

Of ferns and brakes and such-like sights

As tempt out scientific wights

On winter's day; but most his joy

Was finding what's called Osman's Roy."

The district of the Land's End! What a magic charm

these words used to have for me in my childhood ! And now I was within a

few miles of this wondrous locality! Of course my Penzance friends

failed not to take me to the rocky promontory. I gazed on the granite

rocks which defy the fury of the waves of the Atlantic, which roar

terribly. I saw the strange caverns underneath, and the noble mass

surmounted by the moving rock. The Lizard lights in the distance, and

the glow-worms in the hedges, cheered our late return. Of pleasure I had

had a goodly share; but, alas, I had brought no fern to my collection. I

was advised to search Marazion Marsh: ''That is an excellent field for

wild-flowers," said my friends, "and probably for ferns also." So an

early day was appointed, and we traversed the sands, crossed the

railroad, entered a broad highway which was raised above the surrounding

land, and, passing over a bridge built across a slow stream or standing

water, we turned quickly to the left, and began to examine a large tract

of waste land. Of this some was bog, some sandy ground, and some quite

under water. That season had been a late one, and the delicate pink

bells of the bog Anagallis still quivered in the breeze, while a

few spikes of the musk Bartsia yet remained. But what was that

stately plant growing under the shade of the brushwood at some distance

from us, with its somewhat glaucous foliage and tall compound spire of

seed? In my eagerness I forgot the swampy nature of the ground, and

springing forward found myself standing by the plant in question

ankle-deep in water. But I heeded not any such trifling personal

inconvenience, for I had found the object of my ambition, the Royal

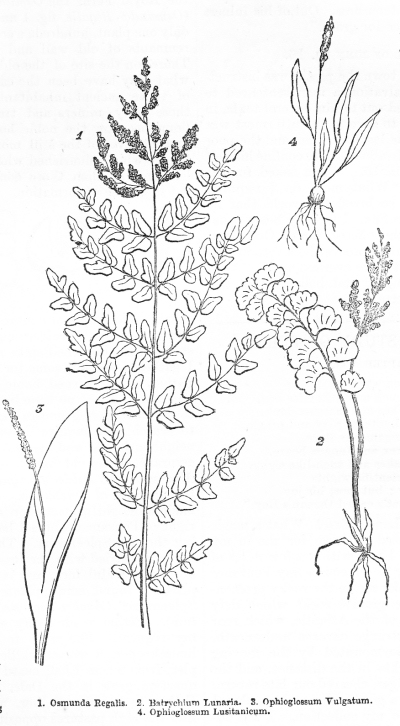

Fern, the Osmunda or Osmund's Roy! (Osmunda Regalis, fig.

1 and a. And

it was not only one plant, hundreds were growing

there, under remnants of old wall and scraps of old hedge. There, on the

site of the old Jewish town, behind what may have been the carefully

planted fences of those ancient inhabitants of the Mara Zion, those

early miners and traders in Cornish tin, flourishes now the noble head

of the English representatives of the still more ancient family, the

family which flourished when rocks only a degree less ancient than those

containing the ore, were yet in course of formation.

The Fronds grew to a noble height, the fruitful ones

more erect than those unburdened with spikes. The fruit was contained in

round cases, like grains, growing in profuse abundance upon the many

stalks of the branched spike at the top of the frond. I gathered

several, some for myself, and some for Esther, and returned home proud

of my new acquisition. I lost no time in writing of my success to my

dear young cousin, and I begged her both to search and inquire

unremittingly in her own neighbourhood, and ascertain the truth of the

assurance of an old herbalist there, that both the Moonwort and

Adder's-tongue were to be found in the pastures of Swaledale. In

the meanwhile we made a delightful excursion along the cliffs to the

right of Penzance, where I had the delight of finding the Sea

Spleenwort. The roof of a cave was fairly tapestried with the broad and

verdant fronds of this beautiful fern, and in one or two sheltered

places I found small plants of the lance-shaped Spleenwort (Aspkenium

marinum and lanceola-tum). Esther made every effort to comply

with my request. She went to the clergyman's old housekeeper, a woman

skilled in herbs and simples, from whom I had heard that the two ferns

in question grew in the Dale. Betty begged Miss Esther to accompany her,

and leading the way into the high pastures opposite her father's house,

she showed her the Adder's-tongue in abundance, telling her that she

gathered a great deal every year to make into ointment for bruises and

swelling. "Don't take none o' them pieces, Miss Esther, to send to your

friend," she said, "for it dies down at this time o' year, and them

pieces is withered. I have some nice bits at home that I have kept for

bookmarkers, and I will give you one o' them." In an adjoining field she

pointed out the Moonwort growing amongst the low herbage, and so

assimilating with it, that an unin-structed observer would only have

supposed it a plant in seed. Betty said that this also made a good

ointment, and that superstitious folks thought that it would open looks

and bring the shoes off horses, but for her part she believed no such

witchery. Esther procured and sent me good specimens of this. Here I was

indeed fortunate. The Moonwort with its double row of crescent leaflets

and branched spike of grain-like seed-vessels lay in my hand, a near

though very humble relative of the noble Royal-fern (Batrychi-um

Lunaria, fig. 2 and b). The Adder's-tongue seemed at first sight

like a miniature of the Field - Arum, the tongue of seeds rising

from the broad undivided frond as from a sheath. The seeds are arranged

in a double row along the simple spike (Ophio-glossum Vulgatum,

fig. 3 and c.) Before concluding my series of visits I was fortunate

enough to receive the gift of a specimen of the pretty little Jersey

Adder's-tongue (O. Lusitani-cum, fig. 4). It differs from our own

Adder's-tongue in being smaller, in having narrower leaves, and there

being two or more leaves to each plant.

No pen can describe the keen pleasure with which I

regarded my collection of ferns. There lay the four Polypodys with their

round uncovered masses of seed-cases, the Scaly Spleenwort with its

scale spread back and cover rent or absent, and the Jersey fern with its

uncovered seed-masses, forming together the coverless order or

Polypodiaceae.

Next were placed the Woodsia with its round

fringed cover; the prickly four-ferns with their round covers fastened

in the centre; the six-shield

ferns with their kidney-shaped covers fastened in the

cut side; the three-bladder ferns with their thin bag-like cover; the

nine-Spleenworts, with their line-like masses and covering opening

towards the middle vein; the Lady fern with its roundish covering

attached by the side; the Hart's-tongue with its long seed masses and

membranaceous covers; the Brake with its seeds on the margin in a line;

the Parsley-fern with its circular masses on the margin; the Hard-fern

with its seed in two covered lines, and the Maiden-hair with its

crescent or roundish masses and thin covering;—all these forming the

covered order or Aspidiaceae.

The small order of the urn-bearing ferns or Hymenophyllaceae

were next, containing only the two Filmy ferns, and the

Bristle-fern. The Royal-fern stood next with an order to itself, the

fruit being naked. We termed this the Spike order or Os-mundacece.

Finally came the Moonwort and Adder's - tongue, also spiked, and

only differing from the Os-mundaceae in the seed case. These represented

the Ophioglos-sacece.

Such was my success. Did I owe it to myself? To my

own application and persevering search? These were themselves the gift

of God, elements bestowedup-on me with which to overcome difficulty. But

these were not my chief aids. Jacob said, in that melancholy scene when

he won his father's blessing by deceit, "I found the venison, because

the Lord thy God brought it to me." And thus when we take up the

study of any part of the works or dealings of God, and seek therein the

teaching of Him who "giveth to all men liberally and upbraideth not,"He

makes the complicated seem simple, the confused clear; He quickens the

vision, both intellectual and physical; He directs the way of our steps

and the tenor of our thoughts, and the samples of His marvellous

creation come into our hands, because the Lord our God beings them to

us.

|