|

THERE is a charm of sweetest potency in the lay of the

poet when it is wedded to the beautiful in external nature. Both song and

scene are doubly enriched by the union. The melodious gush of human

feeling passing over the fair bosom of the landscape, like the south wind

upon a bank of violets, to borrow an image from the great treasury of

imagery, seems, as it were, like "giving and receiving odour." The genius

of Burns to many a stream has lent "a music sweeter than its own." It is

not the material loveliness of the Doon, the Lugar, and the Ayr, though

lovely wanderers by wood and wild are they one and all, that leads the

piIgrim's willing feet so frequently to their banks. It is not the

beauties which Flora discloses among the green links of the Tweed, the

Yarrow, and the Ettrick which bring so litany loving eyes to gaze on their

rippled bosoms. To those who admire the shows and forms of the great

mother in all their native grace, these murmuring beauties of our native

land would in any case be dear. But when to their other attractions is

added the living light of song; when they are associated with the heart

utterances of beings with kindred passions to our own, who have loved, and

hoped, and feared—who have joyed and sorrowed, smiled and wept by their

gushing channels—then, indeed, do they become unto our souls even as

hallowed things, and the spirit yearns to behold them, even as it would to

gaze upon an absent friend, and longs to hear their liquid voices as it

does for that of one whom we have loved with a perfect love. Few are thy

running waters, mine own song-breathing land, which cannot boast their

own peculiar strains; and few,

indeed, are thy song-haunted streams with which these eyes have not, at

one time or other, been gladdened. Beyond the Tweed, however, there are

many Yarrows yet unvisited. Shakspeare’s Avon is to us a dream; the fairy

Duddon and the sylvan Wye, murmur for us in Wordsworth’s verse alone;

while the Ouse of gentle Cowper we can only see "in the mind’s eye,

horatio," as it floweth in placid sweetness through the landscape of "The

Task." Would it were ours, this sweet September day, to thread the mazes

of some one or other of these song-enchanted streams! to tread in the

footsteps of departed genius, and to look upon the scenes which, in days

gone by, the poet loved and sung! The wish is vain. Even in these days of

speedy transit it may not be; so we shall even make a virtue of necessity,

and spend our golden interval of autumnal leisure, in a pilgrimage to

scenery not less fair, though happily more familiar—the land of our own

sweet singer, Robert Tannahill.

The year is falling into the "sere and yellow leaf,"

and the reapers are busy among the white fields of harvest. There is still

a faint lingering indication of nocturnal frost in the morning air, but

the sun, with its golden slants of radiance, from a sky of mingled blue

and white, gives promise of a glorious day, as we shape our course towards

the terminus of the

"South-Western," on our route to the ancient town of Paisley. Our train is

in waiting with a snorting engine at its head, and, punctual to the

minute, we find ourselves in rapid motion along the iron way. There is

something exceedingly exhilarating in a brief rush by rail into the

country. As with the wings of a bird, we are at once borne from the city’s

bustling maze into the freshness and beauty of the scattered farms and

villages. The sense of sight, which has been "cabined, cribbed, confined"

within the weary waste of walls, is again permitted "ample scope and verge

enough," and wanders with a feeling of relief and gladness over the fair

face of nature, while in the very depths of our heart we find an echo to

the poet’s exclamation—

"God made the country, but

man made the town."

Brief space for reflection

is now afforded to the traveller between the Broomielaw and the Sneddon.

There are fine snatches of landscape, however, by the way. Dashing past

the neat little suburb of Pollokshields—the picturesque villas of which

have sprung up as if by enchantment—we have the fine spire of Govan rising

over its girdle of ancient elms to the right; and in the distance beyond,

the brown Kilpatrick hills seem as if they were hastening to meet us. Now

we have a cosie farm-stead rushing past—then a stately mansion,

half-hidden in foliage—and anon we catch a passing glimpse of Crookston’s

shattered tower rising against the horizon to the left. At length,

emerging from the tunnel of Arkleston, the smoke of Paisley is seen

curling lazily to the sky, and the train, passing Greenlaw, with its

verdant lawns and leafy clumps of trees, soon comes to a pause, and

discharges a considerable portion of its living freight.

We have a warm aide to

Paisley and its "bodies." Some of our happiest days were spent in that

locality, and we have never experienced more genuine kindness than amongst

its inhabitants. Nowhere else have we such "troops of friends," and

nowhere else do we meet so many smiling faces and frankly extended hands,

or so many homes where we are certain of a warm and hearty welcome.

Blessings be upon thee and thy denizens, old town! and may the prosperity

which now shines upon thee be of long continuance! May thy trade flourish

and thy comforts increase! and may the gift of song, in which so many of

thy sons have excelled, still find its most faithful votaries in thee!

But, talking of poetry, we are reminded that a young poet of most ample

promise— one whose name has already travelled far on the wings of fame—was

to meet us here; and see, there he is, in front of that stately baronial

pile, the County Prison, awaiting our arrival, and, staff in hand,

prepared for the pilgrimage we

have chalked out for ourselves. As we pass along another friend of kindred

spirit is picked up, and, congratulating ourselves on the best day of the

season, we thread our way to the "west end," and, after a brief interval,

make our exit from the town by way of Maxwellton, in the direction

of Glenifer Braes. This fine range of hills is situated about two miles to

the southward of Paisley—the intervening country consisting principally of

gently swelling undulations, part of which are covered with trees, but the

greater portion being cultivated or under pasture. We are now upon classic

ground, amid scenes which have been immortalized in never-dying song.

Along the path which we are now treading Robert Tannahill, the weaver poet

of Paisley, has often strayed, to glean the sweet natural imagery with

which his lyrics are so delightfully interwoven. The place of his birth

and his boyhood, the scene of his toils and his pleasures, and, alas! that

of his melancholy death, are all in the immediate neighbourhood. Some

half-century ago the poet might have been seen stealing out, on this very

road, in the summer gloamings, when the midges were dancing aboon the

burn, to spend a few hours alone with nature, after the labours of the day

were over. These green knolls have often rung with the echoes of his

flute; and perhaps these very trees which are now rustling in the autumnal

breeze have murmured in harmony with his voice, as he chanted in solitude

the new-born song as it came welling from his heart. The surface of the

country, however, has undergone material alteration since those days.

Where the yellow blossoms of the whin or the golden tassels of the broom

then waved unmolested in the passing wind, the ploughshare has since

passed, and what was formerly a barren wilderness is now a place of

cultivated fertility. Were the poet coming to life again, he would

scarcely recognize, indeed, the haunts of his early love.

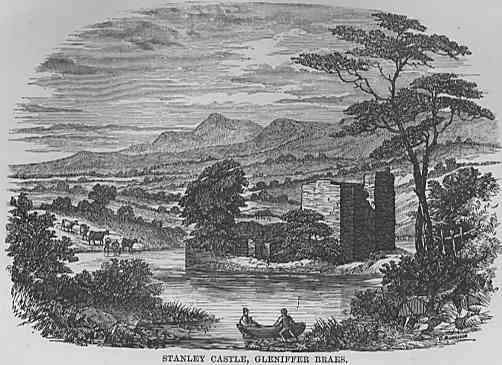

Passing Meikleriggs Moor, where the

monster political meetings of Paisley have been long held, and leaving the

Corsebar Farm behind, we soon arrive at the large reservoir of the Paisley

Water Company, also a new feature in the landscape since the departure of

the poet. At the southwest corner of this large sheet of water, and

generally entirely surrounded by it, stands the ancient and withal

picturesque Castle of Stanley. This venerable pile is alluded to on

several occasions in the writings of Tannahill. Every one will remember

that most beautiful passage in one of his songs,—

"Keen blaws the wind o’er the brass

o’ Gleniffer,

The auld castle turrets are covered wi’ snaw;

How changed frae the time when I met wi’ my lover

Amang the broom bushes by Stanley green shaw!"

Writing in 1804 to his friend and brother poet,

Scadlock, who was then located in Perth, he also refers to the old tower

in the lines,—

"If e’er in musing mood you

stray

Alang the classic looks of Tay,

Think on our walks by Stanley tower

And steep Gleniffer brae."

This seems, indeed, to have been a

favourite haunt of Tannahill. Stanley green shaw, however, is now no more.

Its site is swallowed up in the capacious bosom of the reservoir, and

where the birks once waved in the luxuriance of summer, the mavis no

longer "sings fu’ cheerie, O."

Fortunately, at the time of our

visit, the water in the "muckle dam" is exceedingly low, in consequence of

which the old castle is standing high and dry, so that we are enabled to

inspect it minutely. This edifice, which is of unknown date, consists of a

quadrangular keep about forty feet in height, with a rectangular tower of

equal elevation, originally designed to afford protection to the principal

entrance. Round the top there is a cornice, the corbels of which project

considerably, and seem at one period to have been surmounted by a series

of small turrets. These, with the entire roof, have now disappeared,

however, leaving the structure, which is rent and shattered in various

places, in an exceedingly ruinous condition. The window embrasures are

small and narrow, and the wall is pierced at intervals by loop-holes,

which have doubtless contributed to the defence of the inmates in the

lawless days of old. Every crevice and seam of the weather-beaten castle

is overrun with vegetation— lichens, and mosses, and minute ferns—while

the long grass waves above the walls, imparting to them an aspect of the

dreariest desolation. By a huge gap in one of its immensely thick sides we

make our entrée to the interior of the solitary edifice. The

desolation within is even more striking and affecting than that which

meets the eye outside. The sight of roofless and weed-peopled halls, the

vestiges of chimneys still black with the fires which a hundred years ago

grew dim, of staircases worn by the feet of long, long departed humanity,

of vaults which bring the miserable captives of long ago before the inward

eye, all strike upon a solemn chord of sympathy within us, and excite to

serious meditation upon the transitoriness of all earthly things. Fancy in

such a scene has full scope, and immediately begins to summon up the dead.

The silent chambers are once more teeming with living forms—knights, and

lords, and ladies fair. Here the master of the keep once more prepares him

for the fight—from that window the weeping mistress again looks forth upon

her warrior’s departure, or smiles his welcome home. Pictures of birth,

marriage, and death—the landmarks of all human life, the events of all

earthly homes— start up before us, and we joy or sorrow as they come and

go, as if the creatures of imagination were still our fellow-pilgrims

between the cradle and the grave. But see! upon the green floor there, in

the shaft of sunlight that comes through yonder loop-hole, a bright-winged

butterfly, his glowing tints of red, and black, and brown, resplendent in

the light! How rich the contrast of his radiant hues with the verdant

lichens, upon which he is couched, and the old gray walls around! A ’Tis a

speck of living glory on the very heart of ruin. In wrapt admiration we

gaze in silence on the gorgeous insect, as he lingers for a moment on the

floor of that most ancient hall, and then goes flickering lightly on his

way. ‘Tis a trifling incident; yet, in such a place and in such a mood as

we are, trifles have power to touch the heart. "He preacheth too," as Jean

Paul has said. Ay, this

"Tiny patrician, on whose bannery

wings

Are bright emblazonings,"

is but a type of human grandeur—of

human life; a thing of beauty for a moment seen, and then for ever lost.

Children of a day, we sport from flower to flower, while the sun is in the

sky, and death meets us in the dews of gloaming. Full many a butterfly of

humankind have these sturdy old walls encircled, who has now gone the way

of all living, and long after the trio of friends who are now musing on

this beauteous insect of a day have passed the dark "bourne whence no

traveller returns," they will still lift a weatherbeaten front to the

peltings of the pitiless storm. The things our own hands have made are far

more lasting than we.

Ascending a narrow stair in the

castle, we find ourselves on a commanding platform, which, through a huge

gap in the wall, presents a magnificent view of the country to the

northward: but, as we shall have the pleasure of witnessing the same

landscape on a more extended scale from the brow of the adjoining braes,

we shall not linger here to attempt its description. So, making our exit

by the channel which time has gnawed in the wall, apparently to permit us

a passage, we take farewell of the hoary edifice. About thirty yards or so

to the south-west of the castle, however, we again give ourselves pause to

examine the shaft and pedestal of a curious old stone cross, which, from

time immemorial, stood where the reservoir is now excavated, and which has

long been a puzzle to local antiquaries. We find, to our regret, this

interesting relic removed from the rude socket in which it stood, and

lying ingloriously prostrate on the ground, where it has evidently lain

for a considerable time past. This, in popular parlance, is called the

"Danish Stone;" and tradition ascribes its origin to some of those roving

Norse warriors who were in the habit of favouring our Caledonian sires of

a far distant era with occasional visits of a hostile nature. It was

supposed that one of their leaders had been slain and was buried at this

spot, and that the stone was erected to perpetuate his memory. There can

be little doubt, however, that it is in reality a fragment of one of those

ancient monumental crosses which were at one time so plenteously erected

by our Popish forefathers. Remains of such erections are, indeed, still to

be found in various parts of the country. Examining the prostrate stone,

we find it to be between four and five feet in length, with faint

vestiges, barely visible indeed, of sculptured animals upon one of its

sides, and traces of wreathed work, better defined, carved upon its edges.

What species of animated forms were designed to be represented on this

fragment of the past, it would require more acute eyes than ours

now-a-days to discover; but we learn from Semple, the county historian,

who saw it in 1782, that on what was then the west side, and which is now

the upper one, "there were two lions near the base, and two boars a little

above." The old stone, however, has forgotten the tale which it was

intended to tell; it is now almost a blank, and if permitted to remain

much longer on the cold earth, exposed to the action of wind and weather,

it will soon be indistinguishable from an ordinary piece of mason-work. To

such a favour, indeed, must the proudest monuments of man come at last.

Gradually ascending, we have now the beautiful range of

the Gleniffer Braes immediately before us. That dark ravine in our front,

surmounted with gloomy firs on either side, is the glen from which the

braes derive their name. It is a deep rocky gully, bounded by steep

overhanging walls, and with a brawling torrent rushing foamily down its

rugged channel. Observe, the fine beech at one side of the entrance is

already tinged with gold, as if October had untimely dashed it with his

mellowing wing. Fain would we guide thee, gentle reader, up that moat

picturesque ravine, for well we know its every linn and pool; but my

lord’s game might chance to be disturbed, or haply we might fall in with

some one of his lordship’s surly keepers, than whom we had rather

encounter a raging bear. So we must even content ourselves with the

highway, which, as you observe, slopes beautifully up hill to the

westward. Before proceeding, however, we may mention that the scene before

us is supposed by some to be the "dusky glen" alluded to in Tannahill’s

fine song beginning—

"We’ll meet beside the dusky glen, on yon burnside,

Where the bashes form a cosie den, on you burnside.

The spot certainly agrees in all its features with the

scenery referred to in the song; the "birken bower," the "broomy knowes,"

the "sweetly murmuring stream," &c., are all here as the poet has

described them. As if, moreover, to corroborate the statement that this is

the veritable "dusky glen," we may record an incident which we have

learned on the best authority. One sweet summer evening, about the

beginning of the present century, the poet and his brother (Mr. Matthew

Tannahill, who still survives, a hale and venerable old man) were taking

their usual walk together after the toils of the day, on the braes in this

vicinity. By the time they reached the place where we are now standing,

that is to say, immediately below Gleniffer proper, the sun was slowly

sinking beneath the horizon. The whole vale of the Clyde was filled, as it

were, with the level radiance of the departing orb, and the gray hills

were glowing in a warm ruddy hue. What principally attracted the poet’s

attention, however, was the effect which the flood of light had produced

upon certain trees in the neighbourhood, which were gilded as with a

glittering halo by the effulgent beams. On observing the phenomenon he

immediately cried out in ecstacy to his brother, "Look here, Matthew! did

you ever see anything so exquisitely beautiful! why, the very leaves

glimmer as gin they were tinged wi’ gowd." Shortly after this the song

appeared, and the poet’s brother at once remembered the circumstance which

had given birth to the finest verse in the production,—

"Now the plantin’ taps are tinged wi’ gowd, on yon

burnside,

And gloamin’ draws her foggy shroud, on yon burnside

Far frae the noisy scene,

I’ll through the fields alane;

There we’ll meet, my ain dear Jean! down by you burnside.

There is an opinion generally entertained in Paisley

and its vicinity, however, that the locale of the song is a certain

"dusky glen" on the Alt-Patrick burn, about a couple of miles north-west

from our present position. It would be difficult indeed to prove

definitely which of the places the poet had in his mind when the effusion

was written. We are in favour of the Gleniffer theory from the

circumstances above stated, but when the poet’s surviving friends refrain

from speaking authoritatively on the subject we must he moderate in the

advocacy of our views. Either glen is sufficiently beautiful to justify

the taste of the author.

The song of "Gloomy winter’s noo awa" is perhaps the

most popular, as it certainly is the most exquisite of Tannahill’s songs.

There is a melodious sweetness in this strain, combined with a tenderness

of sentiment and a truthfulness of natural imagery, which have rarely been

equalled, and which, unless by a few of the best lyrical effusions of

Burns, have never been surpassed. The scene of this delightful lay now

lies before us, beautiful even as it was when the poet saw it in the light

of his own genius. To the eastward lies Glen-Killoch, towards which, in

the song, he invites his "young," his "artless deane" to stray; to the

west are the "Newton woods," over which the laverock fanned the "snaw-white

cluds" on the "gowden day" alluded to, while "Gleniffer’s dewy dell" opens

its verdant bosom before us. We have heard it prosaically objected to this

song, that the Newton woods are too far west for the ear to distinguish

the laverock’s lilt, while Gleniffer is at hand; and that Glen-Killoch is

a shade too far east for a couple of lovers to visit within the compass of

an easy walk; but assuredly those who made the objection were neither

poets nor lovers, or they would have known better the extent of license

which both poet and lover require for their enjoyments. To the lover no

ramble is too long when his charmer is by his side, and the ear of the

poet is gleg beyond the comprehension of ordinary mortals.

What is the "craw-flower" alluded to in this song? is a

question to which various answers have been returned. The little celandine

of Wordsworth has been pointed out to us as the "craw-flower" of Tannahill,

and also the crowfoot or buttercup of our meadows. It is neither of these,

however. The craw-flower of the poet is the wild hyacinth of our woods,

the hyaciathus non-scriptus of the botanist, which, with its tuft

of blue-bells, sweetens the breath of May and June. The local name of this

beautiful flower is the "crawtae," and by this name also it is mentioned

in the writings of Milton, who, it will be remembered, in Lycidas,

invokes the vales to strew their blooms on the tomb of his lost friend:-

"Bring the rathe primrose that forsaken dies

The tufted crowtoe and pale jessamine,

The white pink, and the pansy freaked with jet,

The glowing violet,

The musk-rose and the well-attired woodbine,

With cowslips wan, that hang the pensive head,

And every flower that sad embroidery wears"

The celandine is not a bell but a star neither is it

blue in colour; and we learn from another song that Tannahill’s

"craw-flower" was blue; but in addition to this, we know that

"feathery breckans" fringed the rocks at the season alluded to in the

song, and every botanist knows that by the time the fronds of the fern are

unfolded the bloom of the celandine is over, while that of the hyacinth is

at its prime. The craw-flower of "Gloomy winter’s noo awa," therefore, is

in reality the sweet-scented blue-bell of the early summer; than which our

indigenous Flora can boast but few lovelier flowers, it is just the image

which a poet would select for sweetness and modesty in the lassie of his

heart.

Our way is now up hill, and as we advance the prospect

gradually widens and becomes more interesting. The character of the

vegetation also becomes altered. Flowers which are unknown on the rich

flats below here bloom profusely in all their native loveliness. The

bracken, the heather, and the myrtle-leaved blaeberry lend a kind of

Alpine feature to the swelling knolls; while fringing the margin of the

path we have the delicate wild pansy, the fairy blue-bell, and the

graceful bed-straws white and yellow. Passing a comfortable looking

farm-house, with a few fine umbrageous plane-trees by its side, one of

which has an immense hollow in its trunk, we at length, in a bend of the

road, arrive at a little natural fountain trickling from a green bank by

the wayside. The gush is small, but unfailing in the highest noons of

summer, and the water is deliciously cool and clear. Full many a

crystalline draught are we indebted to that tiny well, Oft in our rambles

over these braes, alone or in company with valued friends, have we come

for rest and refreshment to this secluded but commanding spot. Many are

the blythe groups we have seen circled around it, while each individual in

turn dipped his beard in its stainless bosom. Fair faces, too, have we

seen mirrored in its waters, while rosy lips have met—substanee and

shadow—on its cool, dimpled surface. Were we a rich man we should gift

thee a handsome basin, thou well-loved little fountain; but silver and

gold have we none; so thou must even content thyself with a humble poet’s

honest meed of praise

THE BONNIE WEE WELL

The bonnie wee well on the breist o’ the brae,

That skinkles sae cauld in the sweet smile o’ day,

And croons a laigh sang a’ to pleasure itsel’

As it jinks ‘neath the breckan and genty blue-bell.

The bonnie wee well on the breist o’ the brae

Seems an image to me o’ a bairnie at play;

For it springs free the yird wi’ a flicker o’ glee,

And it kisses the flowers, while its ripple they pree.

The bonnie wee well on the breist o’ the brae

Wins blessings on blessings fu’ monie ilk day;

For the wayworn and wearie aft rest by its side,

And man, wife, and wean a’ are richly supplied.

The bonnie wee well on the breist o’ the brae,

Where the hare steals to drink in the gloamin’ sae gray,

Where the wild moorlan’ birds dip their nebs and tak’ wing,

And the lark weets his whistle ere mounting to sing.

Thou bonnie wee well on the breist o’ the brae,

My memory aft haunts thee by nicht and by day;

For the friends I ha’e loved In the years that are gane

Ha'e knelt by thy brim, and thy gush ha’e parta’en.

Thou bonnie wee well on the breist o’ the brae,

While I stoop to thy bosom, my thirst to allay,

I will drink to the loved ones who come back nae mair,

And my tears will but hallow thy bosom sae fair.

Thou bonnie wee well on the breist o’ the brae,

My blessing rests with thee, wherever I stray;

In joy and in sorrow, in sunshine and gloom,

I will dream of thy beauty, thy freshness and bloom.

In the depths of the city, midst turnmoil and noise,

I’ll oft hear with rapture thy lone trickling voice,

While fancy takes wing to thy rich fringe of green,

And quaffs thy cool waters in noon’s gowden sheen.

Let us now glance at the picture which is spread before

us, and we verily believe that a fairer one exists not in bonny Scotland.

At our feet is the old Castle of Stanley, with its sheet of water

glittering in the sun; beyond is the magnificent basin of the Clyde,

stretching away to the Campsie and Kilpatrick Hills, with all its

garniture of woods and fields, mansions and farms, villages and towns, set

down as in a map. In the middle distance are Paisley and Renfrew, to the

right our own good city with its canopy of smoke, to the left Elderslie,

Johnstone, and Kilbarchan. Snatches of the Clyde and its tributary Cart

are to be discovered here and there; while long trails of steam mark the

various courses of the rail. To the far right we have the Cathkin Braes,

to the left Strath-Gryffe, with the hills above Port-Glasgow, and the

Mistilaw. On the horizon to the north a grand sweep of the western

Highlands meets the view, with Benlomond and a score of other gigantic

peaks raising their dun crests against the sky. Such are the landmarks of

this glorious amphitheatre; but what pencil or what pen shall do justice

to its beautiful details? Of a truth, not ours. The scene, indeed, baffles

description. It is on too mighty a scale for words, and it contains within

its scope material for countless landscape delineations.

Shortly after leaving the well we reach the summit of

the ridge, when our course from a westward direction turns almost due

south. We have now reached a kind of tableland, consisting principally of

moorland pasture, with here and there large patches of cold arabic soil,

and occasional tracts of peat-bog. The fertile valley which we have been

contemplating becomes gradually screened from our gaze by the brow of the

hill, and a comparatively sterile tract lies before us. We are now wending

our way to a lonely hostelry situated among these dreary moors, and well

known to ramblers from Paisley by the appropriate title of the "Peeseweep

Inn." A few minutes’ walk brings us to the spot. The house is a lowly one-storeyed

edifice, with a peat-stack, at one end, a rowan-tree in front, and a

kailyard behind. Above the door there was formerly a spirited

representation of the bird from which the inn takes its name. The Dick-Tinto

who executed the picture so well in other respects, however, had, by some

oversight or other, neglected to furnish the poor bird with a crest. This

omission was naturally the cause of considerable jocularity among the

gangrel bodies who frequented the house; and whether offended at this

circumstance or not we cannot take upon ourselves to say, but the

peeseweep has taken wing from its former position, and the inn is at

present without a sign. On making our entrée we are kindly received

by mine hostess of the Peeseweep, and are at once shown ben to the spence.

An abundant supply of excellent bread, butter, and cheese, with a jug of

milk which never knew the pump, soon grace the board. Our lengthened walk

has given appetite an edge of exquisite keenness, and the destruction

which immediately ensues is really awful to contemplate. A flowing caulker

concludes the repast; and, let the grumblers in the Times, who have

recently been crying out against the rapacious charges of our modern

Bonifaces, hear and wonder—our united bill is somewhat under a couple of

shillings!

Leaving our inn—the landlord of which is certainly in

his charges a sad laggard behind the spirit of the age—we now turn in a

westerly direction, and pursue our way by a pleasant country path for

about a-quarter of a mile, until we arrive at a bridge, which crosses a

fine frolicsome burn that leaves a moorland loch a little to the

southward, and pursues a devious downward course to the Black Cart, which

it joins somewhere in the vicinity of Linwood. This is the Alt-Patrick

burn, and down its winding way it is our intention, even at the risk of

encountering the gamekeeper, to continue our pilgrimage. Gamekeepers,

after all, are but men, and a "soft answer turneth away wrath." We have

seldom, indeed, come in contact with specimens of this unpopular genus in

our numerous trespasses by wood and wild; and, in the few instances where

we have, a civil word or two—and "civility costs nothing"—have generally

brought us off with flying colours. So, without a thought of evil

consequences, we follow the guidance of the streamlet, and sure a more

playful or more beautiful little water never tempted poet’s foot to stray

adown its sweet meander, and no think lang. The inimitable verse of Burns

is, in truth, justified in every feature,—

"Whiles ower a linn the burnie plays,

As through the glen it wimples;

Whiles ‘neath a rocky scaur it strays,

Whiles in a well it dimples:

Whiles glittering to the nightly rays

Wi' dickering dancing dazzle;

Whiles cooking underneath the braes

Beneath the spreading hazel."

Now it seems to sleep in some sweet pool, as if loath

to leave a spot so fair; anon it is rippling merrily onward, foaming round

some projecting rock that seems to bar its passage, making sweet music to

the enamelled stones; and again it leaps playfully over some tiny linn,

and gushes rapidly on its way, with foam-bells winking on its dark brown

breast. Leisurely we follow its many links and turns, stooping at frequent

intervals to regale ourselves on the wild fruits with which its tangled

margin abounds. The blackboyd is here in many a jetty bunch, while,

strange conjunction, the blaeberry, the hindberry, and the strawberry are

all to be gathered at once in the same nook. Such a meeting of berries we

have never seen before. It would almost seem as if July, August, and

September had agreed among their sweet selves to enrich at once with their

peculiar fruits this favoured burn. How we enjoy the treat! The omniverous

appetite of our schoolboy-days seems to have revisited our inner man once

more, while our heart beats lightly in our breast as in the days o’

langsyne, when

"We plundered the hazel, the bramble, and sloe."

As we advance the banks become more steep and bosky,

presenting at every turn glimpses of beauty which would fill the painter’s

heart with joy. Anon, hazels and rowans of richest red are added to our

sylvan bill of fare. At one spot of peculiar loveliness we turn to scan

our poetical friend’s countenance, expecting to find him in rapt

admiration, gazing on its charms. No such thing the sensuous scoundrel is

absorbed in the mysteries of a rasp-bush, which he is despoiling of its

crimson gems with an avidity approaching to the sublime; while his

companion is gazing with a fox-and-grape sort of expression at an

un-come-at-able cluster of blushing rowans! Steeper and more steep are the

banks becoming, and at length we hear the roar of a waterfall, hidden in

foliage, and half-drowning the sweet song of the redbreast with its din.

Who would have thought the sportive streamlet could have mustered such a

volume of voice? Passing through the gloaming of the wood, we obtain a

glimpse of the cataract, which may be about thirty feet in height. The

water is dashed down in one white sheet, which has a most pleasing effect

as it is seen through its green vale of overhanging boughs. It is a thing

to be seen, however, rather than painted, as the intervening foliage

somewhat destroys its pictorial capabilities. Immediately below the fall

the stream winds pleasantly away through a vast green basin, which has

apparently been scooped out by the floods of countless ages. The waters in

this uninterrupted channel soon resume their gentle character, and while

we rest by its margin a picturesque group of cattle are lazily wading in

the foam-fretted shallows.

This, we suspect, is the scene of Tannahill’s little

pastoral drama, "The Soldier’s Return," which, as a whole, is admitted to

be the least successful of the weaver poet’s productions. Indeed, in

several recent editions of his poems, it is omitted altogether, with the

exception of the fine songs with which it was so profusely interspersed.

Some of these are among his most successful efforts and in one of them he

makes his heroine allude to natural beauties similar to those of this

locality, when she is about to leave Glenfeoch, and her "mammy and her

daddie, O," to go in search of her "braw Hieland laddie, O." The wild

fruits, amid which we have been revelling, are specially dwelt upon, as

witness:

"The blaeberry banks now are lonesome and dreary, O;

Muddy are the streams that gushed down see clearly, O;

Silent are the rocks that echoed sae gladly, O;

The wild melting strains o’ my dear Hieland Laddie, O.

He pu’d me the crawberry, ripe frae the baggy fen;

He pu’d me the strawberry, red frae the foggy glen;

He pu’d me the row’n, frae the wild steep sae giddy, O;

See loving and see kind was my dear Hieland Laddie, O."

Who can doubt that the sweet singer of Paisley has

often, in his country rambles, come down the glen as we have now done! or

that like us, he has partaken freely of the banquet which Nature spreadeth

for our acceptance in the wilderness! We now bid adieu to this charming

little glen, where we have spent a couple of hours right pleasantly and we

doubt not that the laird will heartily forgive our harmless, though

unauthorized intrusion into his most beautiful domains. We shall certainly

accord unto him an equal privilege when he deigns to visit the broad, very

broad lands which rejoice in our lairdship. Like those of the famous "Tom

Tiddler," however, we are afraid they will be somewhat difficult of

discovery.

And now for Elderslie. The distance may be somewhere

about a mile and a-half; and as our shadows are waxing ominously long, we

must not loiter by the way. Indeed, as there is little of a noticeable

nature on the route, we may as well, with the reader’s leave, just skip

over the intervening space, and deposit ourselves at once in that classic

locality. Elderslie, or "Ellerslie," as it is occasionally spelled, is a

small straggling village, principally consisting of two ranges of

commonplace-looking houses, erected on either side of the highway leading

westward from Paisley, and at a distance of fully two miles from that

town. The population, who are for the most part of the operative class,

numbers about one thousand two hundred, or thereby. It is as the

birthplace of Scotland’s great warrior-chief, Sir William Wallace,

however, that Elderslie is chiefly remarkable. As Burns has poetically

said,—

"At Wallace’ name what Scottish blood

But bells up in a springtide flood!

Oft have our fearless fathers strode

By Wallace’ aide,

Still pressing onward red-wat-shod,

Or glorious died."

The spot on which he was born, the scenes of his

numerous battles with the enemies of his country’s independence, his

various hiding-places in seasons of adversity—indeed, every place and

object associated with the name of Wallace, is hallowed in the memory of

every true-hearted Scotsman. This brave but ill-requited chief was the

eldest son of Sir Malcolm Wallace of Elderslie, by a daughter of Sir

Ronald Crawford, Sheriff of Ayr. Near the west end of the village a house

is pointed out as the identical edifice, in which the hero first saw the

light. Approaching the spot, and making inquiry, this structure is pointed

out to our admiring eyes by an individual of somewhat crusty appearance,

who is apparently about to enter the auld biggin’. At a glance, we

perceive, from its architectural character and comparatively modern

aspect, that the edifice is of much more recent origin than the date

assigned to it. On expressing our doubts on this point to the individual

alluded to, he retorts, "Ay, but ye’re lookin’ at the wrang place a’

thegither; it’s no the big house ava, but this wee place here whare

Wallace was born. Come in by—never mind the dog—lie doun, sir! (addressing

the dog aforesaid, a most fierce and villainous-looking mastiff that was

straining with dreadful violence on its chain to reach the intruders)

—come in by, and gang in at that door, that’s Wallace’s kitchen." So

saying, he turns on his heel, and disappears, sans ceremonie, in

the doorway. Entering the kitchen, we find it to be a dark low roofed

chamber of small dimensions, but with a fire-place sufficiently capacious

to have cooked a supper, not only for Wallace, but at the same time for a

large section of his army. This part of the structure is decidedly

ancient; but we should imagine it must have been erected long subsequent

to the days of our hero. There can be little doubt, however, that it was

on this very site that the home of Sir Malcolm Wallace once stood.

Unvarying tradition affirms the circumstance; and, as if to corroborate

this, in some measure, about thirty years ago a stone, bearing the

following inscription in Roman characters, was dug from the foundation of

the garden wall: "W. W. W. Christ is only my Redeemer." The initials in

this are supposed to refer to two proprietors of Elderslie, who bore the

name and surname of William Wallace. This curious relic is now, we

understand, in the possession of Alexander Speirs, Esq. of Elderslie. In

the garden there is a venerable old yew-tree, which is popularly known as

"Wallace’s Yew," not, we imagine, from any supposed connection with the

hero, but simply from the situation in which it stands. Repassing our

canine friend, who again takes the full length of his tether, and upon

whom we feel every inclination to bestow a little wholesome chastisement,

we now proceed a short distance further east, for the purpose of paying

our respects to the famous "Wallace oak." This sylvan giant is now the

merest wreck of what it was even a few years ago. Time and the storms of

centuries have done their share of the work, but, worse than all, the

relic-hunters, have been unceasingly nibbling at the once stately tree.

Little more than the blackened torso, indeed, of the old oak remains, with

a few straggling shoots alone showing symptoms of vitality. According to

tradition, Wallace and some of his followers, on one occasion, when hotly

pursued by the vindictive Southrons, found shelter and safety among the

leafy branches of this tree. We shall not inquire too curiously into the

probability of the story, lest in this sceptical age we get laughed at for

our pains; but the fact that the ancient and sadly scathed oak has been

for centuries associated with our favourite national hero’s name should

render it an object of interest to every patriotic Scottish breast. In the

year 1825 the trunk of the Wallace oak measured 21 feet in circumference

at the base, and 13 feet 2 inches at the height of 5 feet from the

round. It was then 67 feet in altitude, and the branches extended 45 feet

east, 36 west, 80 south, and 25 north, covering altogether a space of 19

English poles. Since then it has been sadly shorn of its fair proportions,

and probably in the course of a few years it will be numbered among the

things that were. Taking off our hats in reverence to the decaying giant,

we bid it farewell, and turn our faces toward home. The light is beginning

to thicken, and the "lengthening train of craws" are hieing them away to

their roosting-places in the distant woods. Half-an-hour’s smart walk

brings us to Paisley, where we receive a kindly welcome in the domicile of

our friend and companion. |