|

WITH the appearance of Duntocher and Old

Kilpatrick, as seen from the Clyde, the majority of our readers must be

perfectly familiar. Passing Dalmuir by the steamer, a fine range of hills

is seen stretching from east to west, and approaching the margin of the

river immediately previous to its enlargement into the noble proportions

of a frith. About half-way up the swelling slopes, and partially concealed

amid wooded knolls, a tall chimney or two, and several gigantic factories,

mark the site of Duntocher; while a church tower, and a scattered

congregation of houses, reposing in the shadow of the hills and in close

contiguity to the stream, indicate to the observant passenger that the

famous birthplace of Ireland’s patron Saint is before him. Those who have

only seen these localities, however, from the bosom of the Clyde, can form

but a faint conception of the landscape beauties with which they are

environed, and must of necessity have entirely overlooked the numerous

objects of historical and traditionary interest which are situated in

their immediate neighbourhood. Few parishes in Scotland, indeed, command

such a rich variety of scenery as Old Kilpatrick, or are invested with

more pleasing associations. Forming the boundary, as it were, between the

Highlands and Lowlands, it combines the picturesque charms of both in

their most striking and attractive aspects. Yet, in these days of "cheap

trips" and "pleasure excursions," by river and rail, comparatively few of

our holiday wanderers dream of visiting this locality. It has not the

enchantment of distance to recommend it to their admiration. It is too

near home to be properly appreciated. The crowd must have their shilling’s

worth of steamer or train, and consequently often "go farther and fare

worse;" while delicious snatches of scenery like those in this vicinity

are left in a great measure to the solitary enjoyment of such eccentric

ramblers as ourselves.

In consequence of the facilities of transit afforded by

the ever-passing river steamers, the tract of country between Glasgow and

Kilpatrick must be, even to the majority of visitors to the latter, a

species of terra incognita. We propose, therefore, in accordance

with our usual plan, to conduct our readers to that locality by what may

not inappropriately be termed the "overland route." There are, of course,

more ways than one to Kilpatrick, as there are to most places else. We

might have taken, for instance, the low road by Yoker and Dalmuir; or the

high road by Garscube and New Kilpatrick. We take neither, however; but

evince our characteristic wisdom by steering a judicious middle course,

which, although neither the shortest nor the easiest, has the merit of

being at the same time the most picturesque and the most original. Leaving

the city, then, by Anderston Walk, we make our way towards Partick. It is

rather a difficult matter to leave the city in this direction, as she

seems determined, in her westward progress, to keep pace with you. In our

boyish days there was a "world’s end" somewhere about Finnieston, but

where the pole may have shifted to now-a-days is beyond our ken. "Our auld

respeckit mither" has long passed that once well-known landmark, with her

stately streets, crescents, terraces, and squares. What an ogress the old

lady must be! gardens and green fields, cottages and mansions, once

familiar to our eyes, have disappeared in scores within her capacious maw,

and still the cry is "give, give!" There is, in truth, "life in the old

jade yet;" she is still justifying her noble motto, and continuing to

"flourish."

Passing Sandyford, we turn aside to the right for the

purpose of paying a brief visit to the West-end or Kelvin Grove Park. This

is a recent acquisition of the municipality, and one which must be

considered a decided ornament, as well as a sanitary benefit to the city.

The rapid extension of the town in this direction rendered such a

breathing space necessary; and if the opportunity had been once neglected,

a lasting injury would undoubtedly have been inflicted on the community.

The Lord Provost (Stewart), Magistrates, and Council, therefore, acted

wisely when, in 1853, the lands of Kelvin Grove and Woodside came into the

market, to secure them for the benefit of the public. The original outlay,

something like £90,000, was, it is true, a heavy sacrifice, but it was

confidently anticipated that a large proportion of the sum would be

realized from building feus on certain parts of the grounds—an

anticipation which time has shown to be perfectly correct. These fine

grounds are situated on the eastern bank of the classic Kelvin, which,

under a fringe of trees, flows somewhat lazily past the spot. They are in

all about forty-two acres in extent, and present an exceedingly agreeable

variety of surface. Along the stream there is a stripe of level sward; but

from this they slope gradually upwards, in gracefully swelling terraces

and banks, to a very considerable height. From a design by Sir Joseph

Paxton, the surface is beautifully intersected with walks and carriage

drives, turning and twining in every direction—now gliding under stately

rows of trees—now meandering amidst blooming borders and gay parterres,

and anon winding in the sunshine round terraces of smoothest and freshest

green. From the summit, which is now crowned with long ranges of majestic

edifices, there is a prospect of great extent and loveliness. At the

spectator’s feet are the groves and glades of the Park itself alive with

sauntering groups—women and children, men and maidens, in couples, or

pacing along in solitary speculation. Here two lovers are seated apart

discoursing soft nothings—there a party of wild youths are smoking the

fragrant weed, and "laughing consumedly," while yonder, with spectacled

nose and arms akimbo, measuring his lonely round, is the professor or

preacher pondering what to-morrow, from chair or pulpit, he shall give

forth. Looking beyond, we have a long stretch of the Clyde and all its

bustle of trade and commerce, with the heights of Kilpatrick and

Kilmalcolm rising in the distance. To the southward, over the green slopes

and meadows of Renfrewshire, are the braes of Gleniffer—Tannahill’s own

braes—the Fereneze Braes, Craig of Carnock, Neilston Pad, Ballygeich,

where Pollok of the Course of Time spent his boyhood and youth, and

to the south-east the green-wooded braes of Cathkin and Dychmont. To the

northward, again, we have a glimpse of the Campsie and Strathblane Hills,

with a Highland Ben or two peeping through the gap of the Lennox. From

this commanding spot, indeed, may be scanned the principal landscape

features within eight or ten miles of Glasgow, with nearly all the towns,

and villages, and hamlets, and chateaus included within that range. Thus

far we have had nothing but words of praise to bestow upon the Park and

its patrons. Before leaving its precincts, however, we must indulge in a

word or two of animadversion. The great staircase leading to the uppermost

terrace—one of the most spacious and beautiful erections of the kind we

have ever witnessed—is stowed away in a corner, where it must be looked

for—positively searched after—before it can be seen. Why, in the name of

all that is picturesque, was not this grand structure placed under the

centre of the towering range which crowns with dignity the brow of the

slope? In such a position it would have formed an imposing feature in the

landscape of the Park, while in its present situation it is nearly, if not

altogether lost. Could this oversight—for such we must consider it—not yet

be remedied? Then there is the Kelvin, a perfect common-sewer, redolent of

the most unsavoury comparisons. Can nothing be done to

cleanse its foul bosom of that perilous stuff which loads the air

with unholy odours, and threatens the lieges with fevers and other

deadly maladies which are born of miasmatic stench? There was at one time

some talk of preventing this pollution, by means of draining and

filtration, but hitherto the evil is unmitigated, and every ornament that

is added to the grounds, is therefore but an additional enticement to the

breathing of unwholesome airs. "Reform it altogether," say we to the

authorities, or at once renounce the credit which you claim as the

founders of a new place of recreation for the people. Beautify the grounds

as you may, while this evil remains without remead, we can only look upon

your efforts in landscape gardening, as the adornment of a lazar-house -

the whitening of a sepulchre.

"Then, farewll to Kelvin Grove, bonnie lassie, O;

And adieu to all I love, bonnie lassie, O;

To the river winding clear,

To the fragrant-scented brier,

Even to thee of all most dear, bonnie lassie, O."

But we have yet a lengthened way before us, and must be

jogging. Passing Clayslaps, and having stolen a glance at our friend

Sandie Baird’s beautiful and neatly-arranged beds of pansies, surpassing

in their loveliness of hue the "glory of a Solomon," we proceed for a mile

or so along the highway to Dumbarton, when we turn to the north, near the

west-end of Partick, by what is locally denominated the "Craw-road."

An agreeable walk of some half-hour’s duration between

verdant hedgerows and overhanging trees—during which we pass in succession

the mansion of Woodcroft, the auld warld hamlet of Balshagrie, and that

most stately but most melancholy edifice, the Lunatic Asylum at Gartnavel—

brings us to Annisland Toll, where, turning to the left, we pursue our

journey in a westerly direction. From the number of coal-pits in this

vicinity, it is obvious that the valuable black diamond abounds to an

extraordinary degree in the bowels of the land over which we are now

treading. Carboniferous districts are generally anything but attractive to

the lover of landscape beauty. The country around us, however, is an

exception to the rule. Those fine woods to the north-east are portions of

the spacious pleasure grounds of Garscube House, the handsome seat of Sir

Archibald Hay Campbell of Succoth, Bart., M.P.; while the dense masses of

foliage immediately to the left of our present course, conceal from our

view the mansion of Jordanhill, the family seat of Jas. Smith, Esq., a

gentleman who has long been a distinguished ornament of the scientific and

literary circles of the west of Scotland.

In former times the Jordanhill estate was held by a

family named Crawford, one member of which achieved a name in his

country’s history by an exploit remarkable alike for coolness and bravery.

This individual was Captain John Crawford of Jordanhill, who, in 1571,

with a small band of followers, succeeded in taking, by an ingenious

stratagem, the Castle of Dumbarton. After the battle of Langside and Queen

Mary’s flight to England, this strong fortress, then deemed all but

impregnable, was held in the interest of the royal exile by the Governor,

Lord Fleming, who steadily refused to surrender it to the party then in

power. Crawford, who had been a servant of the unfortunate Darnley, and

was of course a bitter enemy to the Queen, formed the resolution of

seizing this stronghold, and putting her friends to flight. Accordingly,

on the occasion alluded to, with a select party of his retainers, he

marched towards the castle after night-fall, provided with ropes and

scaling-ladders, and having in his company an individual who was familiar

with every step upon the rock. Arriving at the castle about midnight, and

being completely screened from observation by a dense fog, they commenced

operations. After encountering great difficulties and considerable alarm,

occasioned by one of the men being seized with a convulsive fit while

half-way up the ladder; they at length attained a position on the walls,

and, after striking down a sentinel, who was about to give warning of

their presence, they rushed upon the sleeping garrison, shouting, "A

Darnley! a Darnley!" and easily succeeded in effecting its capture. The

assailants did not lose a single man, while so complete was the surprise

of the opposite party that they surrendered almost without a blow, and of

course their loss was also trifling. The Governor managed to make his

escape; but a number of individuals of distinction were made prisoners

within the walls of the castle, among whom was Hamilton, Bishop of St.

Andrew’s, who was immediately tried for participation in the murder of

Darnley, and being convicted, was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and

quartered. Benefit of clergy had by this time gone completely out of

fashion, and his reverence, who was generally detested, shortly afterwards

expiated his crimes on a tree at Stirling. The following wicked Latin

couplet is said to have been written on the occasion:—

"Vive diu, felix arbor, semperque vireto

Frondibus, ut nobis talia poma feras."

Passing the entrance to Jordanhill, from which a

lengthened avenue of stately trees leads to the house, which is

effectually concealed from view by its fine sylvan screen, we turn again

towards the north by a rough country road to the "Red Town." This is the

name given to several ranges of colliers’ houses, which are quite as

plain, unattractive, and uncomfortable in appearance, as such edifices

generally are. We are rather surprised, however, with one adjunct to the

Red Town, namely, an extensive and somewhat elegant school. From its

capacity one would imagine it was designed to accommodate not only the

juvenile but also the adult inhabitants of the village, and probably,

indeed, the grown-up natives are fully as much in need of the schoolmaster

as the rising generation. The moral and intellectual culture of the mining

population has hitherto, we are sorry to say, been too much neglected.

Such an institution as the one alluded to should undoubtedly be attached

to every collier village; and we were gratified to learn, from a little

fair-haired girl, whom we overtook with a couple of pitchers, returning

from the well, that there were "a gey wheen o’ scholars in the schule

baith on ilka days and Sundays."

From the Red Town the road gradually ascends to a

considerable eminence called Clober, or Cowdonhill, which commands an

extensive and beautiful prospect of the surrounding country. On the summit

of this elevation, and overshadowed by a girdle of trees, stands the

ancient mansion of Cowdon, a dreary, desolate, and wobegone looking

edifice. This structure is two storeys in height, and has at one period

been of considerable extent. It was in bygone years the seat of a family

named Crawford. About the beginning of last century it passed by marriage,

with the extensive estates attached to it, into the possession of a

certain John Sprewl, who thenceforth adopted the double surname of Sprewl

Crawford. From various dates which are still legible on the walls it would

appear that the building has undergone extensive alterations at different

periods. Over the doorway there is a heraldic carving, much defaced by

time, but on which a bird and a star are still observable. On one of the

gables, which has lately been rebuilt with the old material, there is a

star, with the date 1666; and on the front of the tenement, in a sadly

dilapidated condition, is a sun-dial, with the names of John Sprewl and

Isabella Crawford inscribed on it, with date 1707.

Strange stories are current in the countryside

concerning this "bleak house." A spot is pointed out in the neighbourhood

where the grass will not grow, and which, according to tradition,

was the scene of some dark deed in days of yore. Couple this fact with the

circumstance that a quantity of human bones were, many years ago, found in

a portion of the edifice, which was known as "Cowdon’s den," and the

intelligent reader will have no difficulty in coming to the conclusion

that the house must be haunted. Such, according to popular rumour, is

indeed the case. People shake their beads when spoken to on the subject,

and hint more than they are willing to express. One old lady of the

Crawford family, we are informed, having hidden a pot of gold in a niche

of the wall during her life, could "get nae rest in her grave" afterwards

until she had revealed the secret. A story is also told of a certain

wicked laird, a friend and associate of Claverhouse, the persecutor, who

was an occasional visitor here. This worthy, on his death-bed, is said to

have ordered the servants to keep immense quantities of coals on the fire,

that he might have a foretaste of what was awaiting him in the state of

existence upon which he was about to enter. Of course such an uncanny end

could forebode no good for the future; and it is said the laird is still

doomed to revisit, "in his shirt of fire," the glimpses of the moon! If

such be really the case (and we are not by any means prepared to prove the

reverse), it must certainly gall him sadly, if spirits care for such

sublunary things, to witness the decay which has recently befallen his

former dwelling. Externally it has indeed a most ghastly and doleful

appearance, while the interior, sic transit gloria mundi, is

inhabited, not by owls and bats, but by several families of colliers. A

section of the edifice has also been fitted up as a counting-house and

store for a neighbouring colliery. We ask a decent-looking woman, whom we

meet at the door of the venerable mansion, if she is not afraid to live in

a house which bears such an ominous character. "Atweel no," she replies,

"I’ve leeved here for the last four years, and never saw onything waur

than mysel’, unless maybe now and then a fou man. I’m thinking," she

continues, "the wae drap whisky‘s the warst speerit that now-a-days enters

the auld sickle o’ a biggin’."

Before leaving Cowdonhill, we may mention that a

curious relic of antiquity was for many generations in the possession of

the family. This was a silver spoon, the mouth-piece of which was not less

than three inches in diameter, and had the following legend inscribed on

it

"This spoon I leave in legacie

To the maist-mouthed Craufurd after me.

"1480"

At a subsequent date the following limping but pithy

lines were also engraven on this gigantic table implement:-

"This spoon you see

Is left in legacy;

If ony pawn't or sell’t,

Cursed let him be."

Descending the brae in a northerly direction, a few

minutes’ walk brings us to the Forth and Clyde Canal, which we cross a

little to the westward, and again proceeding towards the north, are

speedily at the famous gate of Garscadden. This place was formerly a

favourite resort of holiday ramblers from Glasgow and Paisley, who came

for the purpose of inspecting the principal entrance, which is somewhat of

an architectural curiosity. The gateway is a massive yet elegant

structure, of castellated form, and, being unlike in size and appearance

to any edifice of a similar kind in the west of Scotland, it excited in a

high degree, on its erection, the wonder of the common people, who formed

numerous myths to account for its origin. What these were we need not now

rehearse, as the gate has long ceased to be a nine days’ wonder, and is

but seldom visited. The house and estate of Garscadden are at present in

the possession of John Campbell Colquhoun, Esq. of Killermont and

Garscadden. In the early part of last century the lairds of Kilpatrick (in

which parish we now are) were famous for their devotion to the cup. Like

Tam o’ Shanter and his cronie, the Souter, they aft "were fou for weeks

thegither." Anecdotes of the wild doings in these days are still rife in

the parish, and as one of them refers to a former laird of Garscadden, we

may as well give it here. A party of these roystering country squires

were, it seems, on one occasion engaged as usual in a deep drinking match,

when one of the company observed the laird to fall suddenly quiet, while a

strange expression passed over his countenance. The observer said nothing

regarding the circumstance, however, and the merriment went on for some

time as formerly. At length,

"In the thrang o’ stories tellin’,

Shakin’ hands and joking queer,"

another individual remarked "Is na’ Garscadden looking

unca gash the nicht?" "And so he may," said the individual first alluded

to, "for he has been, to my knowledge, wi’ his Maker during the last half

hour; I noticed him slipping awa’, puir fallow, but didna like to disturb

the conviviality by speaking o’t!" It was even so; the poor laird had died

"in harness."

About a mile due north from Garscadden House, which is

finely embowered in woods and gardens of the most luxuriant growth, rises

Castlehill, a gentle but commanding elevation, crowned with a tiara of

lofty trees. Towards this point we now wend our way, amid leafy hedgerows

dappled with flakes of bloom, and loading the breezes, as they come and

go, with sweetest perfume; through daisied pastures studded with

picturesque groups of kine; and by corn-fields rippled with verdure, and

palpitating, as it were, to the song-bursts of the sky-cleaving lark. Now

we pass a comfortable farm-steading, where

"Hens on the midden, ducks in dubs are seen,"

while our unwonted presence is greeted by the house

dog’s honest but rather unwelcome bark; and anon we are lingering by some

lonely patch of planting, reckoning the number of voices that swell its

choral hymn, or the number of bloomy eyes that are winking in the fitful

radiance that keeps coming and going through its fluttering canopy of

leaves. We soon find ourselves on the summit of Castlehill. This spot was,

in ancient times, "when wild in woods our noble fathers ran," a station or

fort on the celebrated wall with which the Roman invaders endeavoured to

check the ceaseless incursions of the unsubdued Caledonians. From its

commanding position, and the vast extent of country which it overlooks,

this must have been a post of considerable importance to the baffled

"masters of the world." "Graham’s Dyke," as the immense barrier which then

existed between the Forth and Clyde is called in popular parlance, passed

immediately over the hill on which we are now stationed. This vast

military structure, commenced by Agricola and completed by Antonine, was

about twenty-seven miles in length from river to river. It consisted,

according to the best authorities, of a great fosse or ditch, averaging

forty feet in width, by about twenty in depth, and extending in one

unbroken line over hill and plain. On the southern side of the ditch, and

within a few feet of its edge, was erected a rampart of mingled stones and

earth, about twenty feet in height and twenty-four in thickness at the

base. This rampart, or agger, was

surmounted by a parapet, behind which ran a level platform for the

accommodation of the defenders. Within the wall, and generally

approximating to it, was a regularly causewayed military road, while it is

supposed that not fewer than nineteen forts were erected at various

distances along the line. In the lapse of centuries, the traces of this

mighty bulwark have become in a great measure obliterated. The plough has

passed over the greater portion of its course, and it is only here and

there, by slight indentations of the soil, that it can be now discovered.

From time to time, however, pieces of rude sculpture, carved stones, urns,

and tablets have been discovered along its track—interesting relics of the

haughty strangers who, long, long ago, sought dominion in our land. Two

inscriptions were dug up many years ago at Castlehill, and are now, to all

practical intents and purposes, as effectually interred again in the

bowels of the Hunterian Museum. One of these has a number of rude figures,

emblematic of a Roman victory over our Caledonian forefathers, carved upon

it, with an inscription referring to the completion of a certain portion

of the wall. Mr. Stuart, in his caledonia Romana, gives the

following translation of the legend inscribed upon it:—

"To the Emperor Cæsar Titais Aelius

Hadrianus Antoninus

Augustus Pius, father of his country,

The Second Legion, Augusta,

(Dedicate this, having executed)

4,666 paces."

The second stone was discovered in 1826 by a

neighbouring farmer, and was presented by the proprietor of Castlehill to

the Hunterian Museum. It is a votive tablet, and was dedicated "to the

eternal field deities of Britain."

On the summit of Castlehill faint outlines of the Roman

encampment are still traceable. A belt of trees has been tastefully

planted around the spot, while the interior is one unbroken verdant area,

save that one lone tree, seemingly by accident, has sprung up near the

centre. While we are here a flock of cattle are scattered about the

enclosure peacefully chewing their cud, the cushat is cooing among the

branches overhead, and the blackbird piping on a leaf-hidden pedestal. It

is difficult, indeed, in these times to realize to ourselves the idea that

the "pomp and circumstance" of ruthless war have ever marred the scene.

Yet here the Roman helmet has gleamed, the Roman sword has clashed, and

here man has encountered man in dire and deadly feud. But

"All these are silent now, or only heard

Like mellowed murmurs of the distant sea."

The prospect from Castlehill is of the most magnificent

description, and would, to any lover of landscape beauty, amply recompense

the journey of a day. To the north is seen the full range of the

Kilpatrick Hills from Dumbuck to their western termination. Looking

westward over a finely undulating country, adorned with towns, villages,

and mansions innumerable, we have the Campsie range from the peak of

Dungoyne to Kilsyth. Turning gradually from the south towards the west, we

have the valley of the Clyde from Tintoc to Dumbuck spread as in a map

before our gaze, with Dychmont, Cathkin, Ballygeich, Neilston Pad, and the

Renfrewshire Hills, forming the picturesque outline of the horizon. To

attempt a description of a scene so rich and so infinitely varied in its

features, would, in truth, but be to exhibit our own utter incapacity: and

as self-esteem forbids that we should parade our own deficiencies, we

shall content ourselves with quietly recommending the reader to take stick

in hand and witness it on his own account, while we make our descent on

Duntocher.

Immediately to the north of Castlehill passes the

highway from New Kilpatrick to Duntocher, along which, in a westerly

direction, we now pursue our course. A pleasant walk of about two miles,

principally down hill, brings us to the village of Faifley—a kind of

suburb of Duntocher. These villages, with Hardgate, form as it were one

irregular and straggling, but cleanly and comfortable looking township.

The houses are, for the most part, plain two-storeyed edifices, and in

many instances have small gardens attached to them. The population are, in

general, either directly or indirectly connected with the extensive

factories of Messrs. Dunn & Co. In 1808, when the works at Duntocher first

came into the hands of the late William Dunn, Esq., the village was almost

deserted. The former proprietors had lost heart, and everything was in a

languishing condition. Mr. Dunn, a man of indomitable energy and

perseverance, who had raised himself from a humble rank in society by his

industry and shrewdness, speedily infused new life into the concern. The

works were gradually extended and improved under his vigilant and

enlightened superintendence, until at length they attained a high state of

efficiency; and the working population increased from 150, the original

number, to upwards of 1,500. By the almost unprecedented success of his

manufacturing operations, Mr. Dunn at length achieved a splendid fortune,

and died in the possession of one of the finest estates in the west of

Scotland. At his decease, a few years ago, the bulk of the property thus

accumulated passed into the hands of his surviving brother, Alexander

Dunn, Esq., the present proprietor.

In proportion to its size, Duntocher seems to he amply

supplied with the "means and appliances" of religious and intellectual

culture. There are no fewer than five places of worship in its immediate

neighbourhood, to each of which is attached an educational establishment;

while there are several other schools supported by parties unconnected

with any local congregation. We understand that there are also several

libraries, by means of which the reading portion of the population have,

at a moderate rate, their literary requirements abundantly gratified.

The situation of the village is highly romantic, and

many of the walks in its vicinity are really of the most delightful

description. In the background are the beautiful Kilpatrick Hills, scarred

with their picturesque glens, down which streamlets are ever tumbling in

foam, or stealing gently under the long yellow broom; while immediately

below is the fertile valley of the Clyde, with its verdant slopes, its

stately mansions, and never-ceasing traffic. The inhabitants generally, as

might indeed be expected, have a more robust and healthful aspect than is

ordinarily to be seen in less happily situated manufacturing communities.

On a hill of moderate height, which overlooks Duntocher,

there existed until recently distinct traces of an extensive Roman

encampment or fort. These are now almost obliterated; but from time to

time many valuable relics of art— produced by the builders of the great

wall—tablets, altars, vases, &c., have been discovered at this interesting

locality. Most of these have been deposited for preservation in the

Hunterian Museum. Some curious subterranean chambers, supposed to be of

Roman origin, were also discovered in the vicinity of the fort in the year

1775. In one of these an earthen jar was found, with a female figure

formed of reddish clay, and a few grains of wheat. At the foot of the hill

there is a bridge, which is also popularly supposed to have been erected

by the Romans, but which, notwithstanding a Latin inscription to that

effect, by Lord Blantyre, who repaired the structure in 1772, is asserted

by long-headed antiquaries to have no more claim to that honour than what

may arise from the circumstance that the stones of which it is composed

were probably taken from the neighbouring fort. We make no pretensions

ourselves to skill in these matters, and shall not presume to express an

opinion on the subject. We may mention, however, that when seen from the

water-worn channel of the rivulet, the bridge has an ancient and

picturesque appearance; and that we should not like to call its antiquity

in question where two or three of the Duntocher folks were gathered

together. Right or wrong, they are determined to have it a Roman edifice,

and would, there is reason to fear, be inclined to deal anything but

gently with an obstinate incredulant. Talk ill of Habby Simson at

Kilbarchan, inquire for a "bull" at Rutherglen, or a "steeple" at Renfrew

but by all means avoid speculating on the genuineness of the bridge at

Duntocher, if you have the least regard for the good-will of the natives.

Leaving Duntocher, we now take our way towards the

village of Old Kilpatrick, which is situated on the northern bank of the

Clyde, about a mile to the westward. Immediately after our departure from

Duntocher, we pass on the left the fine policies of Auchentoshan, the

handsome seat of Alexander Dunn, Esq., and a little farther on the mansion

and grounds of Mountblow, likewise the property of that gentleman. For

beauty of site and extensive command of scenery these stately edifices,

which are in close proximity to each other, will certainly bear favourable

comparison with any in the lower ward of Clydesdale. In the grounds of

Auchentoshan, several faint vestiges of the Roman barrier are traceable;

and in the gardens of Mountblow, there is an ancient monumental cross,

which is supposed to be of the twelfth century, and is similar to those

which have been found at Cantyre and in the Hebrides. This curious relic

was used for some time by way of foot-bridge over a neighbouring burn, and

was only rescued from that degraded position by the late Mr. Dunn, who had

it removed to its present more secure and more honourable site. In

consequence of the friction to which it was then subjected, the carving on

one side of the cross has been entirely effaced; while that on the other,

from lengthened exposure to the weather, has become very obscure. The

inscription is perfectly illegible, and two nondescript figures on the

upper portion, with a confused kind of ornament, are all that can now be

perceived. Time and the elements have indeed taken from it irrecoverably

the tale which it was commissioned to unfold. That this interesting relic

of a long vanished age may be preserved for a more lengthened period from

the destructive influences of "the wind and the rain," we would venture to

suggest to Mr. Dunn that it should be immediately placed under cover.

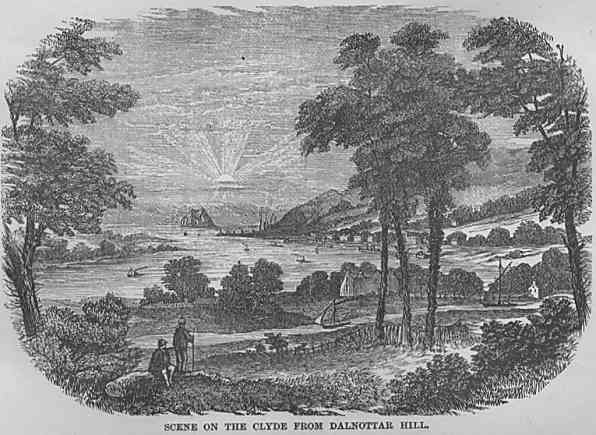

About half-way between Duntocher and Kilpatrick there

is a gentle eminence called Dalnottar, from the brow of which is obtained

one of the most lovely and richly variegated prospects imaginable. The

Clyde, now swelling into the character of a frith, is seen stretching away

into the distance of the Cowal hills, its bosom fretted with numerous

ships and steamers plying busily to and fro between the various ports. On

one hand is the Kilpatrick range of hills terminating in the rocky height

of Dumbuck while at their base, along the irregular margin of the water,

Kilpatrick, Bowling, Dunglass, and the gigantic rock of Dumbarton, are

brought at a glance before the gaze of the spectator. On the south side of

the river are Erskine House, the seat of Lord Blantyre, and its

beautifully wooded banks and braes, with Port-Glasgow and the hills above

Greenock in the distance. The scene altogether is of the most delicious

description, and we need not wonder that it has often tempted the painter

into the exercise of his art. Such of our readers as remember the old

Theatre Royal, Queen Street, will doubtless recollect the famous

drop-scene, taken from this point by the celebrated Naismith, which was so

highly appreciated as a work of art that not less a sum than five hundred

pounds was offered for it by the manager of one of the London theatres.

The prospect from this "coigne of vantage" has frequently been transferred

to the canvas since; but we question if it has ever been more faithfully

or artistically rendered than in the instance to which we have alluded.

Commending the spot to the professional attention of our modern aspirants

to landscape honours, we resume once more our downhill course. We may

mention at parting, however, that the tasteful little residence on the

brow of the hill was occupied for several years by our late highly

respected town-clerk, Mr. Reddie, and his family.

The village of Old Kilpatrick is situated on a level

space of ground between the base of the adjoining hills and the Clyde. It

is of no great extent, and consists principally of a single street, which

forms a portion of the highway between Glasgow and Dumbarton. The houses

are generally of the plainest architectural description, and several of

them are indeed in a half-ruinous condition. There is a number of cosie-looking

dwellings about it, however; and, from a pretty extensive application of

whitewash, the place has, on the whole, a clean and tidy aspect, while the

numerous well-kept gardens about it increase the attractiveness of its

appearance, and at the same time augur well for the home comfort of the

inhabitants. At the west end of the village stands the parish church, a

plain but neat edifice with a handsome tower; and around it, in a spacious

church-yard, "the rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep." There are several

curious gravestones and monuments in the ground, and one is pointed out to

us as that of St. Patrick. There is no inscription on the monument, but

from its appearance it must be of a date long subsequent to the age of the

great frog-destroyer. This individual is traditionally said to have first

seen the light in this vicinity. As in the case of the birth-places of

other illustrious personages, however, there seems to be some doubt on the

subject; and whether "his mother kept a whisky-shop in the town of

Enniskillen," as the popular Irish song has it, or whether he came of the

"dacent people" of Kilpatrick, it will probably be no easy matter

now-a-days to determine. There are two other places of worship besides the

Established Church in the village, namely, a small but neat edifice in

connection with the Free Church, and an old United Presbyterian

meeting-house of somewhat dreary appearance. The place altogether, indeed,

has rather an "auld warld" air, and has apparently undergone but little

alteration for many years.

A short distance west from the village is Chapelhill, a

spot which is remarkable as having been the terminating point of the Roman

wall. Formerly it was supposed that this immense structure extended to

Dunglass Castle, but modem antiquaries, after minute investigation, have

become satisfied that it was at this locality that the terminal fort was

erected. Many relics of Roman art have been discovered here, and it is

even deemed probable that within this elevation a number of subterranean

chambers may yet remain uninjured. Two tabular stones were found at the

Chapel-hill, in the year 1693, by Mr. Hamilton of Orbiston, and presented

by him to the University of Glasgow. These stones, from the inscriptions

upon them, appear to have been erected by the sixth and twentieth legions

of the army, to commemorate the erection of the wall and to perpetuate the

memory of the reigning Emperor Antoninus Pius. On one of them is a figure

of Victory, with a laurel wreath upon her brow, and an olive branch in her

hand. Earthen vases and Roman coins have also been discovered at

Chapelhill, which, besides its interesting antiquarian associations,

possesses charms of a scenic description which will abundantly repay a

visit from the poet or the painter.

After lingering for several hours in the vicinity of

Old Kilpatrick, now speelin' the richly wooded braes, every alteration of

position revealing a new picture to our gaze, and anon threading the mazes

of some nameless glen or deli, radiant with bloom, and musical with the

voices of linnet and of thrush, we return to the "Red Lion" to satisfy

those cravings which, in spite of landscape beauty or sentimental

association, are continually reminding us of our non-chameleon nature. The

poet and the rambler are, alas! alas! even as other men, and must

ultimately draw their inspiration from such gross materials as the beef

steak and the "tappit hen."

Having taken "our ease in our inn" for a brief space,

we proceed to the ferry (for Kilpatrick, unfortunately for herself as well

as for her visitors, has no wharf), and paying our "three bawbees," are

safely deposited on board one of the river steamers, which, in somewhat

lees than an hour afterward, is "blowing off" within a few yards of the

Glasgow Bridge. |