|

GLASGOW and PAISLEY, although situated some seven miles

or so apart, are, by the facilities of steam transit, now placed, so far

as regards time, in almost immediate juxtaposition to each other. A

quarter of an hour now suffices to transport the traveller, on business

bent, from the Broomielaw to the Sneddon—from the smoky domains of our

beloved Sanct Mungo to those of his venerable brother in the "odour of

sanctity," Mirrinus. So far as speedy communication is concerned, the

railway has left us almost nothing to wish. The country which lies between

the great industrial centres of the Clyde and the Cart, however, is of the

most beautiful and fertile description, and contains, moreover, several

objects of historical and sentimental interest, the due inspection of

which requires a more leisurely mode of progression than that of the iron

way. Our readers will therefore be pleased to accompany us in our present

ramble, as on former occasions, a la pied. We may hint,

however, for their encouragement, that there is a probability of our being

driven to the rail by fatigue on our return, as we propose leading them

round a pretty considerable circuit, and into digressions innumerable.

Our favourite route to Paisley is, of course, the

longest one, which is that by the margin of the Canal. Taking our start

from Fort-Eglinton, a short walk brings us to Shields Bridge, at which

point, on the south side of the water, the picturesque little village of

Pollokshields has recently sprung into existence, with a degree of

rapidity which fairly rivals the go-a-head Yankee system of town

development. This miniature community is composed of elegant cottages and

villas, each edifice having its own belt of garden ground walled in, and

tastefully planted in front with flowers and shrubs, and in the rear with

kitchen vegetables. The greatest variety of architectural taste, moreover,

seems to prevail in this rising suburban settlement. Some two score or so

of tenements are already erected, or are in process of erection, and

scarcely two of them are similar in design or construction. Each

individual proprietor seems to have had his own ideal in "stone and lime,"

and every man’s house is as unlike his neighbour’s as possible. Should the

same determined diversity of style continue to prevail, Loudon’s

Encyclopcedia of Cottage Architecture must soon become a dead letter,

so far as Glasgow is concerned, as a walk through Pollokshields will be as

instructive to the student as a perusal of that ponderous though valuable

volume, with its endless disquisitions on projecting porches, ornamental

chimney-stalks, peaked gables, rustic arcades, and mullioned windows. It

must be admitted, however, that so far as it has gone, this variety has,

on the whole, an exceedingly pleasing and picturesque effect, and that we

know few places in the vicinity of our city where we would more readily

wish for a snug cottage home, if "the lamp of Alladin" were for a brief

period ours.

The banks of the canal between Glasgow and Paisley,

artificial though they be, are as rich in natural beauty as the winding

margin of many a river. In various places they are finely wooded, while

throughout their entire length they are fringed with a profusion of our

sweetest wild flowers. Every here and there, also, glimpses of the

surrounding country are obtained—in some cases extending for many miles

around, and embracing scenes of great fertility and loveliness. As we pass

along, the reapers in picturesque groups are busy in the bright yellow

fields. Occasionally, also, the voices of juvenile strollers from the

purlieus of the city are heard on the tangled and bosky banks, where they

come in search of the hips and haws and the blackboyds, which, however,

have scarcely yet attained the necessary degree of ripeness. At intervals,

"few and far between," one of the Company’s boats passes lazily to its

destination; while every now and again a solitary angler gazes

despairingly at his float, and mutters "Nothing doing" to our passing

inquiries concerning his piscatorial success. About four miles from the

city, the Cart approaches within a few feet of the canal. At this point of

the stream we find the yellow water-lily (nuphar lutea) growing

abundantly, with its broad cordate leaves and bright golden flowers

covering the surface of the water. A number of other fine plants also are

thickly strewn along the alluvial margin. Among these are the handsome

wood crane’s-bill (geranium sylvaticum), several stately species of

thistle, flinging their snowy locks to the passing breeze, and the rough

burr-reed with its green sword-like leaves guarding the shallows of the

streamlet, and forming an impervious shade for the water-hen. A dense wood

on the opposite side of the Cart at this place, forming part of the

extensive estates of Sir John Maxwell of Pollok, seems to be well stocked

with game and other wild birds, and we have often heard with delight their

peculiar cries and notes while lingering at the spot during the spring and

summer gloamings. Here, too, we have observed for several successive

seasons a pair of those sweet, though in this part of the country somewhat

rare songsters, the black-cap warblers (curruca atricapilla), which

seem to have bred in the vicinity, although with all our skill (and in our

school-days it was famous) we have failed to discover the well screened

nest.

About half-a-mile farther on we pass the spot where, on

a green bank of the Cart, stood for several centuries the picturesque

castle of Cardonald. This venerable relic of other times has, however,

been demolished within these few years, and a neat modern farm-steading

has been erected on its site. This was at an early period a seat of the

Stewart family, who held extensive possessions for a lengthened series of

years in Renfrewshire. In the reign of James the Sixth, Walter Stewart,

Prior of Blantyre, was lord of Cardonald. From him it passed into the

hands of Lord Blantyre, his heir, in whose family it has continued ever

since. Crawfurd, in his

History of Renfrewshire,

mentions that in his day the lands of

Cardonald were well planted and "beautiful with pleasant gardens." The

remains of these are still in existence. On the fine green lawn which lies

between the modern edifice and the canal, and which is thickly strewn with

cowslips in the early summer, are a number of stately old forest trees,

while the garden still contains several fruit-trees of great age and

considerable size. In front of the present house is a stone taken from the

walls of its more venerable predecessor, on which is carved the figure of

a casque or helmet, with the motto "Toujours avant" (always forward), and

the initials J. S., date 1565. At a short distance to the north, on a bend

of the Cart, are the extensive meal mills of Cardonald, with a group of

cottages and kail-yards, occupied apparently by the operatives engaged in

the establishment. A more delightful locality altogether it were difficult

to imagine. Wood, water, and variety of surface, are here to be seen in

beautiful combination; and we can only regret that it has been divested to

a considerable extent of the charm of historic association, by the removal

of the "howlet-haunted biggin" ‘which for so many generations graced the

scene with its presence.

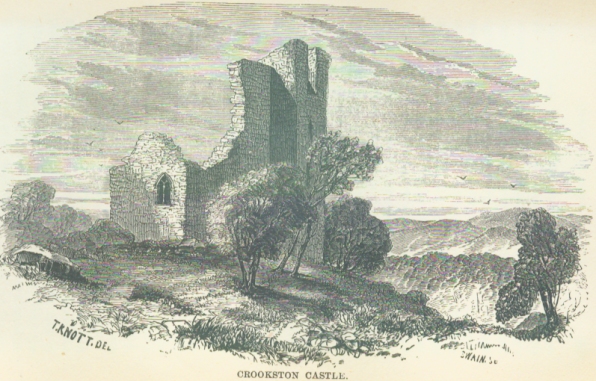

Immediately alter passing Cardonald the ruins of

Crookston Castle are seen on a rising ground to the west, towering proudly

over the intervening woods. Crossing the canal at this point, and passing

along a somewhat circuitous route, we find our way, after a walk of about

a mile, to this interesting and highly romantic spot, which, from its

connection with the name and memory of the unfortunate Mary, must ever be

dear to the sentimental rambler. In the time of Crawfurd this venerable

building, which is situated on a bold bank of the Levern (which joins the

Cart at a short distance to the north), consisted of "a large keep and two

lofty towers with battlemented wings." Since that period a considerably

greater portion of its walls have owned the crumbling influences of time

and the elements. Only one shattered tower has kept its original altitude,

and even it has been in a great degree indebted for its preservation to

the considerate attention of Sir John Maxwell, on whose property it

stands, and who has caused its rent sides to be secured and bound together

by strong iron bars. The same gentleman has also, within the past few

years, procured the removal of the

debris which in the course of centuries

had accumulated around the base of the edifice, and by that means has

brought to light a number of antique doors, windows, and staircases, with

several other curious architectural features, which had been long hid from

the gaze of the antiquary. A couple of vaulted chambers—one of which is in

total darkness, and the other only lighted by a narrow loop-hole—are all

that now remain in anything like a state of entirety. One is almost afraid

to surmise to what vile uses such dreary dungeons may have been put in the

rude days of old, when a lordling’s caprice was cause sufficient for

imprisonment or even death to the helpless and haply unoffending serf: On

climbing with some difficulty the narrow and decayed staircase, and gazing

on the thick darkness which reigns in one of these cheerless cells, we can

almost fancy that we hear the sigh of some hopeless captive floating

through the gloomy and stifling air; and we must admit that we are fain to

return to the blessed light of day, while a feeling of pride and gratitude

springs up in our heart, to think that in our land not even the vilest

criminal can now be condemned to such a loathsome and unwholesome den. The

rampart and moat of the castle, which are of considerable extent, and

convey a vivid idea of the magnitude and grandeur of the edifice in its

days of pride and power, may still be distinctly traced.

The barony and castle of

Crookston seem to have derived their name from Robert de Croe, a gentleman

of Norman extraction, who held

extensive possessions here in the twelfth century. In the following

century the heiress of this individual was married into the illustrious

family of Stuart, who thereby became lords of the extensive baronies of

Crookston, Darnley, Inchinnan, Neilston, and Tarbolton. Every student of

Scottish history is aware that Henry Darnley, the heir of this ancient and

noble house, having won the affections of his Queen, the beautiful but

unfortunate Mary, was married to her in the year 1565. Tradition asserts

that it was at Crookston, one of the seats of the handsome though foolish

young lord, that the brief courtship of the ill-fated lovers took place;

and an old and beautiful yew-tree, which stood in the garden a little to

the east of the castle, was said to have been a favourite haunt of the

royal lovers in the hours of gentle dalliance which preceded their

ill-assorted and ultimately tragical union. The remains of this fine old

tree were removed in 1817 by Sir John Maxwell, it having been sadly

destroyed previously by the depredations of ruthless relic-hunters. A

portion of the timber, we may mention, has been appropriately formed into

a model of Crookston Castle. This interesting object is preserved at

Pollok House, where the visitor is also shown three large sections of the

yew, which seems to have been a tree of considerable age and size. The

number of snuff-boxes, drinking-cups, and ornaments of various kinds, said

to be formed out of Queen Mary’s tree, is almost incredible. Every

curiosity-collector, from the Land’s End to John o’ Groat’s, can boast one

or more fragments of it although it must be admitted that, like the wood

of the "true Cross" which was so extensively diffused during the Middle

Ages, the genuineness of the article is, to say the least of it, in many

instances extremely problematical.

Sir Walter Scott has made a sad

blunder in his novel of The Abbot, by representing Mary as

witnessing at Crookston the battle of Langside. It is well known that the

unfortunate Queen stood on an

eminence near Cathcart during

that decisive engagement, which occurred at least four miles to the east

of.Crookston. The intervening ground, also, is of such a nature as to

render Langside invisible from this locality. On being informed of the

error which he had thus made, Sir Walter at once admitted the fact, in a

note to the revised edition of the Waverley Novels, but he refused

to alter the text, as he considered that by so doing the dramatic interest

of the romance would be considerably diminished. Another error regarding

the stream which flows past the castle has been perpetuated by many who

have written concerning Crookston. This fine rivulet is the Levern, and

not the White Cart, as has been generally believed. The fact that the

junction of these two streams occurs in a beautiful spot about half-a-mile

to the northward of the ruins has probably led to this confusion of their

names.

The memory of Scotia’s unfortunate

Queen—a memory steeped in tears—has been associated with many a lovely

scene, but with none more so than Crookston. Pennant, who visited the spot

in 1772, truly says,—"The situation is delicious, commanding a view of a

well-cultivated tract, divided into a multitude of fertile little hills

;" and Scott has made Queen Mary

remark, that the castle commands a prospect as wide almost as that which

is seen from the peaked summit of Schehallion. Alike rich in material

beauty and sentimental interest, it is no wonder that Crookston is

annually visited by thousands of pilgrims, or that it has ever been a

favourite haunt of the poetic brotherhood. The author of "The Clyde," to

whom we have been previously indebted for several apt quotations, thus

describes the spot:—

"Here raised upon a verdant

mount sublime,

To heaven complaining of the

wrongs of time,

And ruthless force of sacrilegious hands,

Crookston, their ancient seat, in ruin stands;

Nor Clyde’s whole course an ampler prospect yields

Of spacious plains and well-improven fields,

Which here the gently rising hills surround,

And there the cloud-supporting mountains bound."

Tannahill alludes to the

ruins in one of his sweet lyrics—

"Through Crookston castle’s

lonely wa’s

The wintry wind howls wild and dreary?

And our own Motherwell, who many a

time and oft lingered in pensive mood by the time-honoured pile, has

celebrated its charms in one of his most elegant compositions, of which

the following are the concluding lines:—

"Tis past—she rests—the scaffold hath

been swept,

The headsman’s guilty axe to rust consigned-

But Crookston, while thine aged towers remain,

And thy green umbrage woos the evening wind—.

By noblest natures shall her woes be wept,

Who shone the glory of thy festal day:

Whilst aught is left of these thy ruins gray,

They will arouse remembrance of the stain

Queen Mary’s doom hath left on history's page—

Remembrance laden with reproach and pain,

To those who make like me this pilgrimage!"

Many an anonymous bard also has

endeavoured to express in verse the feelings which the shattered and

dreary tower, with its wall-flowers scenting the dewy air, and its

clamorous train of daws startling the echoes with their hoarse cries, has

excited in his breast. One of these nameless voices of the heart we must

give,—

"Thou proud memorial of a former age,

Time-ruined Crookston; not in all our land,—

Romantic with a noble heritage

Of feudal halls in ruin sternly grand,—

More beautiful doth tower or castle stand

Than thou! as oft the lingering traveller tells,

And none more varied sympathies command;

Though where the warrior dwelt the raven dwells:

With tenderness thy tale the rudest bosom swells.

"Along the soul that pleasing sadness steals

Which trembles from a wild harp’s dying fall,

When fancy’s recreative eye reveals

To him lone musing by that mouldering wall,

What warriors thronged, what Joy rung through thy hall,

When royal Mary—yet unstained by crime,

And with love’s golden sceptre ruling all—

Made thee her bridal home. ‘There seems to shine'

Still o’er thee splendour shed at that

high gorgeous times

How dark a moral shades and chills the heart

When gazing on thy dreary deep decayl"

A favourite haunt withal of Flora is

Crookston, and the botanist will find in its shady moat a number of our

Most beautifull, and several of our most rare indigenous plants. Among

these are the cuckowpint (aram maculatum), with its curiously

formed flowers in spring, and its spikes of bright scarlet berries in the

autumn months; the tuberous moschatell (adoxa moschatellina), and a

rich variety of others.

The trailing bramble, the brier with

its soft-folding blossom, the sloe, the hazel, the rowan-tree, and the

haw, are strewn in the most picturesque profusion around the spot—a very

girdle of arborescent beauty to the hoary tower. It would almost seem as

if Nature loved especially to adorn the scene which had been hallowed by

the presence, in a long past age, of the fairest and the most unfortunate

that ever bore the sceptre and crown of regal dignity. How often must the

fond fancy of the exiled Queen have flown from the gloom of her dreary

prison-walls to this fair spot, which every season decks with a beauty of

its own! Burns has put words of lamentation into the mouth of Mary; and it

would almost seem that the scenery of Crookston was in his mind’s eye when

he penned the following verse, so true is it to the character of its

spring landscape:—

"Now blooms the lily by the bank,

The primrose down the brae,

The hawthorn’s budding in the glen,

And milkwhite is the slae,

The meanest hind in fair Scotland

May rove their sweets amang,

But l, the Queen of a’ Scotland,

Maun lie in prison strang."

Crookston is lovely at all

times and seasons; but we feel, while musing by its hoary towers, that the

period most appropriate to wander by the "lonely mansion of the dead" is

indeed that in which we have made our rambling pilgrimage to the locality.

The primrose and the violet of spring have long been numbered among the

things that were; the last rose of summer has fallen from the leafy brier;

the lark is silent in the meadow, and the merle in his noontide bower. The

gathering harvest in the whitened fields, the woodland falling into the

sear and yellow leaf, the harebell hanging its head as if in woe, and even

the liquid pipings of the red-breast telling of approaching decay to

everything of bloom, are all suggestive of pensive feeling, and

appropriately harmonize with that "luxury of woe" in which one loves to

indulge beneath the shattered wall, around which, as with the ivy,

melancholy memories are entwined.

Before leaving

Crookston, we may mention that after the tragical death of Darnley

the estates and honours of Lennox were bestowed upon Charles Stuart,

second son of the Earl of Lennox. This individual, however, dying without

issue, they were resigned to the crown by Robert Stuart, Bishop of

Caithness, the next in lineal succession. After this the lands and castle

of Crookston passed through a variety of hands, until they were finally

purchased from the Montrose family, in 1757, by Sir John Maxwell, the

ancestor of the present proprietor, who, as we have previously remarked,

has exhibited his respect for the memory of her whose brief residence here

has for ever hallowed the locality, by the judicious measures he has

adopted for the preservation of the mouldering edifice. But for the

attention which he has thus manifested, the stately remains of Crookston

Castle must soon have been levelled with the dust, and the place which has

known its pomp and grandeur for many a long century should have known them

"no more for ever." The antiquary, and he who loves to drop the tear of

sympathy over the dark fate of the unfortunate Mary, will have reason for

many years to feel grateful to him who has thus preserved from impending

destruction such an interesting memorial of "what has been." We may also

mention that there is a fine portrait of the beauteous Queen of Scots

preserved at Pollok House, as also authentic portraits of her not less

ill-fated grandson, Charles the First, and the Infanta of Spain, who, it

will be remembered, was at one period destined to be his bride.

Retracing our steps to the canal, we

pursue our devious way by its margin toward Paisley, which is still some

three miles to the northward. On either hand, as we pass, a succession of

fertile fields in all the brightness of autumnal gold, and many of them

already shorn or in process of being speedily so, present a series of

those rural pictures which the famous American reaping machine threatens

soon to banish from our land. In an age of change, while steam is jostling

us in every direction, the hairst-rig remained unaltered in all its

primitive simplicity, a picturesque relic of other times, even as it was

when the fair gleaner Ruth

"Stood In tears amid the alien corn."

How our poets and our painters,

those dreamy worshippers of the beautiful, have revelled in the cheerful

groups of autumn, weaving in immortal verse or tracing on the living

canvas those combinations of the graceful in form and the pleasing in

colour, which, once seen, become unto the heart "a joy for ever!" Listen

to one who first saw the light in the city of our own habitation, the

author of "The Sabbath," and who looked with an attentive and a loving eye

on all the "shows and forms" of ever-varying nature,—

"At sultry hour of noon the

reaper band

Rest from their toil, and in the lusty stook

Their sickles hang. Around their simple fare,

Upon the stubble spread, blythsome they form

A circling group, while humbly waits behind,

The wistful dog, and with expressive look

And pawing foot, implores his attic share."

A delicious picture in

words, which some of our artistic

friends might well translate into the language of the glowing canvas. Or

what say they to the following from the same pen, "alike, but oh how

sweetly different!"

"The short repast, seasoned with

simple mirth,

And not without the song, gives place to sleep;

With sheaf beneath his head, the rustic youth

Enjoys sweet slumbers, while the maid he loves

Steals to his side, and screens him from the sun."

About a mile to the

north-west of Crookston, and on the south side of the White Cart, are the

spacious mansion and grounds of Hawkhead, one of the seats of the Earl of

Glasgow. This fine old house, which is screened in every direction by

extensive and beautiful woods, is somewhat irregular in its appearance.

According to Crawfurd, "it is built in the form of a court, and consists

of a large old tower, to which there were lower buildings added in the

reign of Charles the First by James Lord Ross and Dame Margaret Scott, his

lady, and adorned with large orchards, fine gardens, and pretty terraces,

with regular and stately

avenues fronting the said castle, and almost

surrounded with woods and enclosures, which add much to the beauty of this

scat." This was, we understand, the first instance in Renfrewshire in

which the formal and stiff style of Dutch gardening was introduced. The

house, too, was among the earliest in which modern comfort was combined

with the strength of former times. In 1782 the Countess-Dowager of Glasgow

made considerable improvements on this favourite estate, and formed a new

garden, four acres in extent, and more in accordance with the taste of our

day than its stately but quaint and old-fashioned predecessor. We have

seldom seen finer masses of foliage than the bosky banks of the Cart

present at this place; while in spring and early summer—

"The spot is

wild, the banks are steep,

With eglantine and hawthorn

blossomed o’er,

Lychnis and daffodils, and crow-flowers blue."

The Duke of York—the persecuting

Duke whose name still stinks in the nostrils of the Presbyterian peasantry

of Scotland—when in the plenitude of his power in 1681, "dined at the

Halcat with my Lord Ross," as we learn from an ancient chronicler, who

records the event as one of a memorable nature.

The Hawkhead woods seem to furnish a

favourite haunt for the rook. As we pass we are amused to see an immense

flock of these sagacious birds flying about a neighbouring field,

intermingled with vast numbers of starlings—a kindred species which of

late years has increased to an almost incredible extent in the districts

around Glasgow and Paisley. In our bird-nesting days a starling was indeed

a rare avis.

We had a tradition in our

school that a few starlings from time immemorial had haunted the creviced

walls of Bothwell Castle and the shattered towers of Crookston; but for

miles around the country, as every disciple of Gilbert White in this

neighbourhood well knew, such a thing as a bird of this species was seldom

seen. Another proof of their scarcity, if such were wanted, was the

handsome prices which they could always command in that most curious of

marts, the bird-market. Some seven or eight years ago, however, they began

to increase in numbers around Paisley, where they were treated with the

utmost kindness and consideration; breeding-boxes for their special

accommodation being suspended on every second tree and chimney-top. Under

these fostering influences the starlings "multiplied and replenished,"

until at present they are almost as common in that town as the

house-sparrow; More recently they have begun to congregate in and around

our city; and so plentiful have they already become, that a fine young

specimen can be purchased in the season, by the juvenile ornithologist, at

the price of an old song; while those who, like ourselves, are in the

habit of perambulating the country, must have been startled by the vast

flocks, often consisting of many thousands, which assemble in the autumn

and winter months in the neighbouring fields.

About half-a-mile from Paisley the

canal is carried over the Cart by a handsome aqueduct bridge. This

structure, from which a fine view of the town is obtained, is 210 feet in

length, 27 in breadth, and 30 in height. The span of the arch is not less

than 84 feet. At a short distance to the west of this, and quite adjacent

to the canal, are the remains of the ancient castellated mansion of

Blackhall, in bygone times a seat of the Ardgowan family. Crawfurd

mentions that in his day the grounds of Blackhall "were adorned with

beautiful planting." The glory, however, has now departed from the

locality. The gardens and shrubbery are no more, while the edifice itself

has a blackened and exceedingly dreary aspect. A few minutes’ walk from

this hoary relic of the past brings us into the bustling centre of

Paisley, where, in the meantime, we shall leave the reader to make the

acquaintance of the "bodies" as he best may. |