|

IN a letter to Mrs. Dunlop, the bard of Coila remarks

that one of his dearest aims was the acquisition of sufficient meats to

enable him "to make leisurely pilgrimages through Caledonia, to sit on the

fields of her battles, to wander on the romantic banks of her rivers, and

to muse by the stately towers or venerable ruins, once the honoured abodes

of her heroes." Almost every individual of an imaginative temperament must

have experienced a similar desire. The stream which has been ennobled by

song, the field where freedom has been won in blood, and the gray ruin

where in ages long past the great and the good have dwelt, will always

attract the pensive wanderer, and by their associations awaken in his

bosom emotions of sympathy and reverence. What Scotchman but has felt a

yearning to visit the "banks and braes o’ bonnie Doon," or the green

sylvan windings of Tweed, and to croon to himself amidst the scenes of

their birth, the songs and ballads which have been linked to their names,

and which lend unto them

"A music sweeter than their own?"

What patriot but has longed to muse on the spots where

a Wallace and a Bruce have struggled and bled for the honour and

independence of their native land, or by the shattered and "howlet-haunted

higgins" which have been rendered sacred by their presence, or that of

some of their gallant compeers? It is, indeed, a pleasant way of studying

the history of one’s country, thus to wander up and down, deciphering its

principal incidents, as they have been inscribed by the faithful and

loving hand of hoar tradition on her own green breast; and to find that

though the plough may have passed over the blood-stained soil of the

battle-field, and though the defacing influences of centuries and, the

elements may have banished comfort and security from the once proud and

impregnable tower, leaving it lonely, picturesque, and desolate, still the

memory of "what has been" lingers in living hearts, the cherished treasure

of sire and son, shedding a halo of sentiment around each hallowed spot,

which bids defiance alike to duration and to change.

Scotland is peculiarly rich in this interesting species

of lore; but even in Scotland there are few localities wherein it exists

more largely, or is associated with more beautiful objects, than in those

through which in our present ramble we crave the company of our readers.

In deference to the tropical weather which marks the close of June, we are

fain to depart to some extent from our pedestrian rule, and take advantage

of the means of transit afforded by the "rail." Taking our start, then,

from the Caledonian terminus on the south side of the river, we are soon

careering away in capital style from

"Gude Sanct Mungo’s toun sae smeeky,"

in a direction almost due east. There is something

exceedingly exhilarating to us denizens of the city in a short railway

excursion. The eye, relieved from the monotonous lines of street and their

tumultuous streams of life, revels in the freshness and beauty of the ever

changing scenery which seems in very gladness to go dancing past. One

moment we have the winds playing over the wavy wheat; another brings us a

group of jolly haymakers, with a gush of fragrance from the new-mown

swaths; anon sweeps past a band of hoers, thumping away among the shaw-crowned

ridges of the potato field, "that flits ere ye can mark its place," to be

succeeded by a bloomy tract of beans, suggesting "odorous" comparisons.

Now we have the mansion of wealth, with its green lawns and old ancestral

trees; next a lowly cottage, with its kail-yard, its flower-plot, and its

bee-hives—the guidewife, mayhap, nursing her baby at the door, and

half-a-dozen early-headed younkers tumbling on the green. Here we have a

bridge rushing dinsomely past, there a village with its picturesque spire,

and ere the spectator ean learn its name from the venerable lady at his

side, behold it is among "the things that were," and a landscape with

cattle a la Cooper invites his inspection, and as rapidly

disappears. Talk of a picture gallery! why there is none that for variety

and richness can bear comparison, even for a moment, with the living

panorama of the rail. We are much amused on the present occasion with the

vagaries of a botanical friend, who attempts to exercise his vocation and

exhibit his scientific acumen by enumerating the various species of plants

which he detects growing along the line. While the train at starting moves

slowly, he keeps calling our attention every now and again to what he

calls "magnificent specimens" of his floral favourites; but when the

increasing speed sends the daisy in rapid pursuit of the dandelion, the

dock a-hurrying after the nettle, and the wild rose seems in danger of

breaking her neck in an extremity of haste to escape from the threatened

embraces of the stalwart and jaggy thistle, our friend’s head seems all at

once to grow light, he appears fain to gaze at the more distant portions

of the landscape; and to our infinite relief, we hear no more of his

long-winded Latin names until we have arrived at our destination.

The line between Glasgow and Blantyre, a distance of

some seven miles, passes through a delicious tract of country. There are

two intervening stations, Rutherglen and Cambuslang, at both of which we

stop, although we are somewhat surprised to observe that no passengers are

either taken up or set down, while the booking-offices have rather a

dreary do-little appearance. We should imagine, indeed, from the limited

extent of these towns—the condition of their inhabitants, who are

principally weavers, miners, or agricultural labourers—and the comparative

shortness of their distances from the city, that the returns from either

will cut but a shabby figure in the sum total of the company’s revenue.

There are several fine views of the Cathkin and Dychmont hills from the

line, looking southward; while the vale of Clyde, with occasional glimpses

of its waters, forms the principal attraction to the north. In about

half-an-hour after starting, we are set down at Low Blantyre, which we

immediately proceed to inspect. This neat and cleanly little village is

finely situated on a high bank which overlooks the Clyde, here a beautiful

stream about eighty yards in width. The houses, which are arranged in

squares and parallelograms, are the property, and entirely occupied by the

operatives of Messrs. Henry Monteith & Co., whose extensive mills and

dyeworks are immediately adjacent. Every attention seems to have been paid

by this eminent firm to the moral and physical welfare of the inhabitants.

They have erected a chapel in connection with the Established Church,

capable of accommodating 400 sitters; and we understand that they annually

contribute a handsome sum towards the maintenance of the clergyman. During

the week the edifice is used as a schoolhouse, for the education of the

village children; the teacher being partly supported at the expense of the

Company. All the means and appliances of cleanliness, to boot, have been

apparently provided for the population. An abundant supply of water, for

culinary and other purposes, is furnished from the works; while an

extensive building, with a spacious green attached, affords every facility

for the necessary scrubbing and bleaching. Altogether this appears to be

quite a model of a manufacturing village; everything in apple-pie

order—the tenements comfortable and tidy-looking—and the inhabitants

seemingly healthy and cheerful. The oldest of the Blantyre Mills was

erected in 1785 by the late Mr. David Dale and his partner Mr. James

Monteith. Another was built in 1791. Shortly thereafter, premises for the

production of the beautiful Turkey-red dye, for which the firm has long

been celebrated, were erected; and gradually, from time to time since that

period, the establishment has been extending, until now, we believe,

upwards of 210 horse-power is required for the propulsion of the

machinery, and about 1,000 individuals are engaged in conducting the

various operations.

Following the downward course of the river, we now

direct our steps towards the ruins of the ancient Priory of

Blantyre, which are situated in a beautiful and secluded spot, about

three-quarters of a mile from the village. The footpath leading to the

Priory lies along a finely wooded bank, the leafy luxuriance of which

forms a delightful shade to protect us from the vertical radiance of the

midsummer sun. Under the trees the earth is carpeted with a rich profusion

of vegetation. We observe many of our most graceful uncultured grasses,

with their drooping plumes and silken panicles, waving by the margin of

the Clyde, which, from the impulse of the dam at the Blantyre Works, runs

here with considerable velocity. In the deeper recesses of the wood, we

find the elegant little melic grass (melica uniflora) intermingled

with the glossy leaves of the wood-rush and other sylvan plants. We also

observe the

"Stately foxglove fair to see,"

(digitalis purpurea) nodding its towering

crest of crimson bells, the broad-leaved helleborine (epipactis

latifolia), with its curiously plaited foliage, and those most

beautiful of our indigenous geraniums, the wood crane’s-bill (geranium

sylvaticum) and dusky crane’s-bill (geranium phoeum) growing in

great abundance; while the pink-flowered woundwort, the purple-tufted

vetch, the yellow bed-straw, and a bright profusion of kindred blooms are

thickly strewn wherever an opening in the leafy canopy overhead permits an

entrance to the solar beams. The time of the singing of birds is nearly

past, but occasionally the joyous chant of the wood-warbler, or the merry

trill of the wren resounds through the green gloamin’, and drowns for a

time the hum of countless insects which seem to be enjoying their little

hour of life with music and dance in the genial summer air.

After a pleasant ramble through the tangled mazes of

the wood, we arrive at the Priory, which is situated on a precipitous rock

rising to a considerable height above the Clyde. The building, which is of

a fine-grained red sandstone, has apparently been at one period of great

extent. It is now, however, a complete wreck. A portion of the walls and

gables, with several windows and a fireplace, on the verge of the

precipice, with a kind of vaulted chamber now threatening to fall in, are

all that has been spared by the hand of Time. There are several trees

growing among the ruins, and the walls are partly covered with the

mournful ivy,

"Still freshly springing,

Where pride and pomp have passed away,

To mossy tomb and turret grey—

Like friendship clinging."

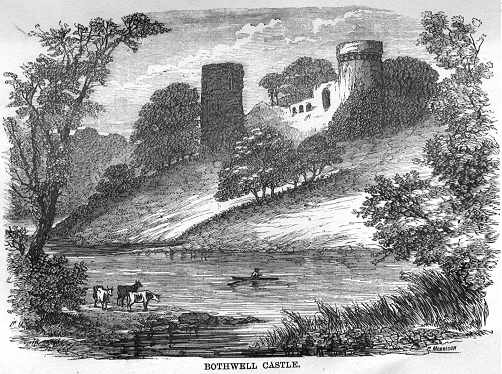

On the opposite bank are the extensive remains of

Bothwell Castle; and the view of this lordly edifice, proud even in decay,

as seen from the Priory window, with the murmuring Clyde between, forms

altogether one of the most interesting and lovely landscapes imaginable.

We well remember that, in a conversation which we had several years since

with the late Professor Wilson of Edinburgh, who lived for some time at

Haliside in this vicinity, he talked in the most enthusiastic terms of

this scene, and stated his conviction that it surpassed anything of a

similar character in Scotland. The eloquent Professor further remarked

that many a summer evening hour he had spent in wandering about this

interesting spot. Little is known of the history of the edifice. To it, in

its utter desolation, the lines of the poet are peculiarly applicable,—

Lonely mansion of the dead,

who shall tell thy varied story?

All thy ancient line have fled,

Leaving thee in ruin hoary."

It seems from an old document to have been founded in

1296, and to have been a cell of the Abbacy of Jedburgh, the inmates of

which are said to have found shelter here occasionally when the incursions

of English marauders rendered the border counties insecure. The names of

Friar Walter of Blantyre, and Frere William, Prior of Blantyre, are

mentioned in ancient historical documents. At the Reformation the

establishment was suppressed, and the benefice, which was of limited

extent, bestowed in name of James VI. on Walter Stewart, a son of Lord

Minto, who was first entitled Commendator of the Priory, and afterwards

Lord Blantyre. At what period the structure was permitted to fall into

decay is unknown, but from the Description of the Sheriffdom of Lanark,

published by Hamilton of Wishaw about a century and a-half ago, it

appears that at that time it was the occasional residence of Lord Blantyre.

Such are almost the only incidents of an authentic nature which history

furnishes regarding this ancient edifice and its former inhabitants.

Tradition says that a vaulted passage under the Clyde

formerly existed between the Priory and the Castle of Bothwell; and Miss

Jane Porter, in the Scottish Chiefs, has taken advantage of this

alleged subaqueous way to heighten the dramatic effect of her story, the

scene of which—as most novel readers are doubtless aware—is partly laid

here. On our first visit to the Priory—a goodly number of years since—our

guide, a school-boy from the adjacent village, told us that according to a

winter evening tale current in the neighbourhood, the popular hero,

Wallace, in a season of difficulty once found shelter from his foes among

the cowled inmates of this establishment. By some means or other the

usurping Southrons learning where their terrible opponent was concealed, a

large party of them at the dead hour of night determined to secure him and

earn the handsome reward offered for his apprehension. To effect this they

surrounded the building, with the exception of that portion overhanging

the precipice, which from its altitude they considered perfectly secure.

While they were thundering at the portal, however, and demanding the

surrender of the Knight of Ellerslie, that doughty chief, nothing daunted,

flipped out by one of the windows, leaped at once over the rock, and

fording the Clyde, made his escape undiscovered. As a convincing proof of

the truthfulness of the legend, we were then taken to see an indentation

in the solid rock below, which bore some resemblance to a gigantic

footmark, and which we were seriously informed had been caused by the foot

of Wallace on that eventful evening. A fine spring issues from the ground

at this spot, the waters of which flow into the sacred footprint; and we

need hardly say that it was with a deep feeling of reverence for "Scotia’s

ill-requited chief" that, on the occasion alluded to, we knelt down and

took a hearty draught from the alleged pedal mark. Our faith, we are sorry

to say, is not now quite so strong. On our present visit we scarcely

discern the resemblance to a footprint which was formerly so obvious; and

although we dip our beard in the gratefully cold and crystalline water,

the delicious awe which we experienced then comes not again over our

spirit.

"Woe’s me, how knowledge makes forlorn!"

and how Time rubs the painted dust off the

butterfly-wing of youthful fancy! How wofully defaced is now the creed of

our sunny boyhood! The fairies are banished from the leafy solitude; no

wandering ghost in the glimpses of the moon haunts the ruined tower of

other days. Well indeed might the poet Campbell exclaim,—

"When Science from Creation’s face

Enchantment’s veil withdraws,

What lovely visions yield their place

To cold material laws!"

Had the royal Dane lived in our matter-of-fact age he

would have found that there is nothing now in heaven or earth which is

undreamed of in our philosophy; nothing to relieve the mind from a "Dryasdust"

and stern reality. Whether we are happier in our dreary wisdom and prying

scepticism than our ancestors were in their gorgeous ignorance and

unsuspecting credulity, is to our mind somewhat problematical. Several of

our poets besides the bard of Hope have expressed regret for the decay of

the old spirit of belief. Wordsworth says in one of his finest Sonnets,-

"Great God! I’d rather be

A pagan, suckled in a creed outworn,

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less folorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea,

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathed horn."

But to our tale. After lingering for a considerable

time at the Priory, and about its picturesque environs, we retrace our

steps to Blantyre, where we cross the Clyde by an elegant suspension

bridge, and proceed to Bothwell, which is situated on a gentle eminence

about half-a-mile to the north-east. By the way we pass a neat little

United Presbyterian Church, recently erected by a congregation the members

of which reside principally in the adjacent villages. Bothwell, like most

other ancient Scottish towns, is somewhat irregular and scattered; but,

unlike the majority of them, it is remarkable for a characteristic

appearance of cleanliness and comfort. It is composed principally of plain

one or two-storeyed edifices, built with a peculiar and somewhat

highly-coloured red sandstone, which seems to be abundant in the

neighbourhood. Most of the houses have garden-plots attached to them, and

the neatness and luxuriance of these attest the general taste and industry

of the inhabitants. A love for flowers, we are happy to observe, is

becoming more common among our population generally; but it is evident,

from the fine condition and profusion of rarer kinds around Bothwell, that

this is no new love among her people. In the vicinity a considerable

number of elegant villas and cottages have been built in tasteful

situations. Many of these, we understand, are, during the summer months,

occupied by the families of some of our most respectable citizens, and by

invalids who find here the benefits to health which result from a genial

atmosphere, and an exquisite series of walks amidst scenery of the

loveliest description. Near the west end of the village is the parish

church, a handsome structure in the Gothic style, which was erected in

1833. At the east end of this building, and attached to it, is the ancient

church of Bothwell, a fine specimen of the ecclesiastical architecture of

other days. This edifice, which is said to have been founded in 1398, by

Archibald, Earl of Douglas, is 70 feet in length and 39 in breadth. The

roof, which is arched and of considerable height, is covered with

sandstone flags, hewn into a curved form resembling tiles. It has been

lighted by a large window in the east end, and a range on either side.

Inside we are shown carvings of the armorial bearings of the noble

families of Hamilton and Douglas, and a stone which was taken from the

base of the old spire, with the words "Magister Thomas Dron," or Tron,

inscribed on it in Saxon letters. This is supposed to have been the name

of the individual who built the church. We are sorry to observe that this

time-worn edifice is at present in a shamefully neglected condition. The

glass is out of the windows, permitting a free passage not only to the

sparrows, which are flying thickly about the nave, but also to the winds

and the rain, which have already wrought sad dilapidation on the

mouldering walls. The heavy tiles, too, are beginning to manifest a

tendency to obey the law of gravitation by tumbling inward. There has of

late been but little care taken of this interesting relic of the past. It

is to be hoped, however, for the credit of the neighbouring gentry, that

measures may speedily be adopted for its preservation from the utter ruin

which now seems impending over it. Leaving the dreary precincts of the old

church, we next, with considerable labour, ascend the church tower, which

is 120 feet in height, and which commands a prospect of great extent and

beauty. At the spectator’s feet, looking eastward, is the village with its

gardens and orchards, some of which are of great extent; beyond is the

green expanse of Bothwell-haugh, the palace and town of Hamilton, with the

finely wooded grounds of the Duke; while the fertile vale of Clyde

stretches away in the distance,—

"To where vast Tintoc heaves his bulk on high,

His shoulders bearing clouds, his head the sky."

In the opposite direction are seen Blantyre and the

leafy policies of Bothwell Castle, Dychmont, and the high grounds of

Kilbride, with the spires of Glasgow towering amidst smoke, and the

picturesque outlines of the Highland mountains bounding the misty horizon.

After lingering on this commanding pinnacle, enjoying the splendid

bird’s-eye view which it affords of the country round, until our head

becomes somewhat light, and we begin to experience that peculiar yearning

to take the shortest way down, which one is startled to feel when looking

over a precipice, we descend from our elevated position to the quiet

church-yard below. In glancing over the memorials of departed mortality,

with which the rank sward is thickly studded, our attention is

particularly directed to a headstone, with the following curious

inscription, the perusal of which, we are afraid, would have ruffled the

equanimity of a Lindley Murray, even amidst the solemnizing influences of

the field of graves:— "Erected by Margaret Scott, in memory of her husband

Robert Stobo, late smith and farrier, Goukthrapple, who died May, 1834, in

the 70th year of his age:

"My sledge and hammer lies declined,

My bellows’ pipe have lost its wind;

My forge extinct, my fire’s decayed,

And in the dust my vice is laid;

My coal Is spent, my iron is gone,

My nails is drove, my work is done,"

Bothwell manse, which is immediately adjacent to the

church, is, without-exception, the most delightful dwelling-place of its

class which we have ever witnessed, and that is surely saying a great deal

in its favour, as every one knows that, go where you will, "from

Maidenkirk to John o’ Groats," the most pleasant of habitations in country

or a town is almost invariably that of the clergyman. it is a neat and not

overly large two-storied edifice, situated in a sweet sunny nook,

embowered amongst fruit trees, and surrounded by gay parterres and green

hedge-rows. It is just the sort of place that one could fancy a poet

should be born in, and here accordingly the light of this world first

dawned upon that most eminent of Scotland’s poetesses, Joanna Baillie, Her

father, the Rev. James Baillie, D.D., was sometime minister of this

parish. He had previously officiated in the Kirk of Shotts, and it is said

that his gifted daughter narrowly escaped being born in that most bleak of

parishes, as the flitting between the one locality and the other had just

been effected when the little stranger made her appearance. The following

record of her birth and baptism is extracted from the parish register of

Bothwell, where we saw the original entry, on a page crowded with similar

announcements regarding the debut of the sons and daughters of

worthy farmers and weavers in the neighbourhood, the majority of whom will

doubtless em now have gone to their final reckoning, without leaving the

faintest

"Footprints on the sands of time."

"Joanna, daughter lawful to the reverend Mr. James

Baillie, minister of the Gospell att Bothwell, and his spouse Dorrete

Hunter, was born the eleventh day of September, and baptized in the Church

of Bothwell upon the twelfth day of the said month by the Rev. Mr. James

Miller, minister of the Gospell att Hamilton, 1762." From this it appears

that the future poetess, who was born on the day after the flitting, was

baptized in the open church when she was only one day old; Although Miss

Baillie left her natal place at an early age, she seems even when far

advanced in life to have recurred with peculiar pleasure to the happy days

which, in the morning of her existence, she spent here. In a poetical

address which she presented, when her long day of life was drawing near

the gloamin’, to her sister Agnes, on the birthday of the latter, she

says,—

"Dear Agnes, gleamed with joy and dashed with tears,

O’re us has glided almost sixty years

Since we on Bothwell’s, bonnie braes were seen,

By those whose eyes long closed in death have been.

Two tiny imps, who scarcely stooped to gather

The slender harebell ‘mong the purple heather,

No taller than the foxglove’s spiky stem,

That dew of morning studs with silvery gem.

Then every butterfly that crossed our view,

With joyful shout was greeted as it flew;

And moth, and ladybird, and beetle bright,

In sheeny gold were each a wondrous sight

Then as we paddled barefoot side by side

Among the sunny shallows of the Clyde,

Minnows or spotted par with twinkling fin,

Swimming in mazy rings the pool within,

A thrill of gladness through our bosoms sent,

Seen in the power of early wonderment"

Nor was the attachment of the poetess to the beautiful

place of her birth a mere empty sentiment, as the following circumstance,

which we learned from a friend in Bothwell, will abundantly testify. About

a month previous to the demise of Miss Baillie, an old lady—the widow of a

respectable inhabitant of Hamilton, and a former acquaintance of the

Baillie family—was suddenly reduced to a state of abject penury by the

burning of her house. Some of those who had known her in "better days" got

up a subscription for the purpose of relieving her necessities, and

amongst others the aged poetess was written to by a granddaughter of the

clergyman by whom she had been baptized. Although in bad health at the

time, she immediately sent an answer to the appeal, enclosing an order for

£15, and expressing an earnest desire to be informed of any other cases of

an urgent nature which might occur among the old town’s-folk. This was

probably the last letter which the hand that had so ably delineated the

passions of humanity ever penned; and thus, in the graceful performance of

an act of charity, the curtain of time fell upon all that was mortal of

this kind-hearted and unassuming woman of genius; We need hardly add that

the memory of this last expression of her love for the "old familiar

faces" is fondly cherished in the hearts of many; for, as she herself

says—

"Words of affection, howsoe’er express’d,

The latest spoken still are deem’d the best"

Adjacent to the church of Bothwell is the parish

school—a handsome edifice of modern erection, in front of which we are

pleased to observe a neatly kept flower-plot. The schoolroom is a spacious

apartment, hung round with maps and other "means and appliances" of a

tuitional description. The avenge number of pupils in attendance is said

to be somewhere about ninety. Attached to the establishment is the

dwelling-house of the teacher, Mr. Hunter, and the place altogether has a

look of "bienness" and comfort which to our imagination seems to indicate

that the lines of this important functionary have, in Bothwell, fallen in

an exceedingly pleasant place. Besides the parish school, we understand

there are other two seminaries in the village—one in connection with the

Free Church, and the other a private school which is under the

superintendence of a lady; so that the shooting of the young idea in

Bothwell would seem to be abundantly provided for.

After visiting some friends in the vicinity, and

benefiting materially by their kind hospitality, we next wend our way to

Bothwell Bridge, the scene of the Covenanters’ overthrow on the 22d of

June, 1679. The particulars of this engagement are familiar to every

reader of Scottish history. The Covenanters, driven to desperation by the

cruelties of Claverhouse and his myrmidons, and encouraged by the victory

which they had achieved at Drumclog a short time previously, assembled to

the number of 4,000, determined to wrest by force of arms, from an

unwilling government, the right of worshipping their Maker in the form

which conscience dictated to be most in accordance with his Word. For the

suppression of this "rising" a large army was immediately collected, the

command of which was entrusted to the Duke of Monmouth, assisted by

Claverhouse and Daiziel, both officers of great energy and experience. The

army of the king advanced to Bothwell on the north side of the river,

while the Covenanters were encamped on the southern bank, and held

possession of the bridge, at that period a narrow and, in the middle,

considerably elevated structure, which was defended by a fortified

gateway. Immediately previous to the commencement of hostilities the

spirit of insubordination broke out in the camp of the Covenanters. The

house was divided against itself, and utter ruin was the necessary

consequence. The moderate Presbyterians and those of extreme opinions

differed as to the extent of the privileges which, in the event of success

attending their efforts, they should demand of the government. In the

midst of their wrangling and bickering, the Royalists attempted to force

the bridge. After a determined struggle with a party of 800 men, under the

gallant Hackston of Rathillet and Hall of Haughhead, to whom the defence

of this important post was entrusted, the attacking party was ultimately

successful. This object attained, they immediately passed over, with their

cannon in front, and formed in order of battle on the south side of the

river. Here the conflict was resumed, and for some time sustained with

considerable warmth; but at length the Covenanters, dispirited by their

repulse on the bridge, disadvantageously posted, and wanting that union so

essential to success in arms, were thrown into confusion and totally

routed; 400 were killed, principally in the retreat, by the merciless

troopers of Claverhouse and Dalziel, and not fewer than 1,200 were taken

prisoners, many of whom were afterwards executed. The author of the

"Clyde" gives a graphic account of this disastrous action in the following

lines:—

"where Bothwell Bridge connects the margin steep,

And Clyde below runs silent, strong, and deep,

The hardy peasant, by oppression driven

To battle, deemed his cause the cause of heaven;

Unskilled in arms, with useless courage stood

While gentle Monmouth grieved to shed his blood;

But fierce Dundee, inflamed with deadly hate,

In vengeance for the great Montrose’s fate,

Let loose the sword, and to the hero’s shade

A barbarous hecatomb of victims paid,

Clyde’s shining silver with their blood was stained,

His paradise with corpses red profaned."

This difference in the dispositions of Monmouth and

Dundee or Claverhouse, as he was then called, is quite in accordance with

history and tradition. The former is said to have on-joined on his

soldiers mercy to their vanquished countrymen; and a pleasing story

regarding him is current in Bothwell. An old house in the village,

recently demolished, is said to have been the scene of a council held by

the commanders of the royal army, previously to the attack on the bridge.

While the council was sitting a little child, unobserved by its mother,

had strayed into the house. After a lengthened search had been made by the

anxious parent for her lost babe, she at last ventured to peep into the

apartment where the military chiefs were assembled, and there, sure

enough, she found it seated on the knee of the gentle Monmouth, who was

fondly caressing it, and endeavouring to amuse it with the glittering hilt

of his sword. The ferocity with which Claverhouse pursued and cut down the

unfortunate Covenanters after their overthrow on this occasion, is well

known; but we think the poet is wrong in supposing, as he does in the

above lines, that it was caused by a feeling of revenge for the fate of

the great Montrose. More probably it was the result of his own fiendish

passions, stirred into extraordinary activity by shame at the recent

defeat which he had sustained at the hands of a few undisciplined

peasants.

The aspect of the bridge and the ground in its vicinity

is completely altered since that period. The gateway has been removed;

and, in 1826, the width of the original structure was increased by 22

feet. The banks of the river, which is here about 71 yards in breadth, are

of great beauty, and retain no traces of the fierce and disastrous

struggle which they once witnessed. Below the bridge, and above it on the

south side, they are finely wooded, and brightened with a profusion of

wild flowers, fully justifying the opening line of the old song,

"O Bothwell bank, thou bloomest fair."

Above the bridge, on the north side, is the spacious

expanse of Bothwellhaugh, formerly the property of James Hamilton, who

shot the Regent Murray at Linlithgow in 1569. Leaving the bridge, and

taking an easterly direction, we proceed by a delightful path, through

fields of waving grain, to the farm-steading which is situated where the

dwelling-place of this dauntless individual once stood. The buildings are

of modern erection, and nowise remarkable unless from associations

connected with their site. Several exquisite views of the palace and

pleasure grounds of Hamilton, however, are obtained from points in this

vicinity, which are well worth visiting; and about a quarter of a-mile to

the east of it there is a picturesque old bridge over the south Calder,

which, according to popular opinion, is of Roman construction. It consists

of a single arch of twenty feet span, high-backed, narrow, and without

parapets. The pavement is composed of small round stones apparently taken

from the channel of the rivulet, and the interstices are thickly

studded with grass and

"Weeds of glorious feature."

This curious structure, now somewhat timeworn and

dilapidated, has altogether a strange old world aspect, and taken in

connection with the rippling dark brown water, and its appropriate sylvan

accessories, would form an excellent subject for the landscape painter.

Returning to Bothwell, we now proceed in a direction

westward from the village, to visit the celebrated ruins of Bothwell

Castle, and the beautiful pleasure grounds of Lord Douglas. This nobleman,

with a liberality which is in the highest degree commendable, permits

strangers to have access to his extensive policies on certain days of the

week. How favourably does such a generous attention to the wishes of his

less favoured countrymen contrast with the exclusive spirit which is

unfortunately so generally manifested by our modern lords of the soil, and

how grateful should the tourist in search of the picturesque feel for the

privilege which is thus considerately and handsomely accorded him! It is

satisfactory to learn that his lordship’s confidence in the popular taste

seems to be fully appreciated, and has been but seldom abused. Many

hundreds annually traverse the beautiful enclosures, and enjoy the lovely

sights around the ancient castle, yet the amenities of the place are but

seldom violated.

A walk of about half-a-mile from the magnificent

gateway, which is surmounted by a carving of the Douglas arms, along a

pathway neatly fringed with verdure, in some places passing through lawns

of closely-cropped velvet turf, in others beneath the shade of majestic

trees, brings us to the front of the spacious mansion of Lord Douglas. The

architecture of this edifice, which is of modern erection, is of the most

unpretending description. It consists of a central compartment and two

wings, the material of the walls being the fine red sandstone prevalent in

the district. The principal apartments are said to be very extensive, and

furnished in the most elegant and tasteful manner, and the walls of the

various rooms hung with pictures by artists of eminence. At a short

distance to the west of the house, on a bold green bank which slopes from

the Clyde, are the stately ruins of Bothwell Castle, the most extensive

and imposing relic of feudal architecture which our country can boast.

Some idea of the former grandeur of this structure may be formed when we

mention that its shattered remains cover a space which is in length 234

feet, and in breadth 99 feet. The walls are in some places 15 feet in

solid thickness, and in height nearly 60 feet. The principal front looking

towards the Clyde consists of a lengthened wall pierced irregularly with

loopholes and windows, and flanked at either end by a lofty circular

tower. The interior presents the appearance of a large court, at the cast

end of which are the remains of certain windows, which seem to indicate

that here stood the chapel of the establishment. There are also several

rooms and vaults in a considerable state of preservation; but although

specific names have been given to some of these places, nothing certain

regarding them can now be known, and the visitor may therefore give his

fancy free scope, and people them again as seemeth best to his own mind.

The walls are in some places beautifully clad with ivy and other climbing

plants, such as the clematis, the greater convolvulus, and the many-tendrilled

hop, while the wall-flower and the nettle nod mournfully from the summits

and the crevices of the walls; and the starling, the owl, and the daw have

long had their homes in the mouldering towers. To quote again from the

"Clyde :"—

"The tufted grass lines Bothwell’s ancient hall,

The fox peeps cautious from the creviced wall,

Where once proud Murray, Clydesdale’s ancient lord,

A mimic sovereign held the festal board"

With regard to the origin of this noble pile little is

now known. In the reign of Alexander II. the barony and castle of Bothwell

were held by Walter Olifard, the Justieiary of Lothian, who died in 1242.

During the troublous period which followed the death of Alexander III. it

fell into the hands of the usurper, Edward I. of England, who resided here

for some time in the year 1301. In 1309 Aymer de Vallance was appointed

governor, and it was while residing here that this individual negotiated

the betrayal of Wallace with the ever-infamous Menteith. At the period

when Bruce gained the battle of Bannoekburn, Bothwell Castle was held by a

Sir Walter Fitzgilbert, as we learn from the following passage in Barbour

:—

"The Earl of Herford frae the melle,

Departed with a great menay,

And straucht to Bothwell took the way,

That in the Inglis mennys fay

Was holden as a place of wer;

Sehyr Walter Gilbertson was ther

Capitaine," &c. -

After the above decisive victory, of course the

Southrons were speedily relieved of their unjust possession, and Bruce

conferred the barony and castle on Andrew Murray, Lord Bothwell, his own

brother-in-law. It seems to have fallen again into the hands of the

English, however, after the death of Bruce, when Scotland was again

invaded by Edward III., as several documents, still in existence, written

by that monarch, are dated at Bothwell. After passing in succession

through the hands of the potent families of Douglas, Crichton, Hepburn,

and Stewart, it was finally settled on the ancestors of the present

possessor in 1715.

The scenery in the vicinity of the castle is of the

finest description, including several views of the reaches of the Clyde,

with its wooded banks, above and below, of the most striking description.

A fine feature in the landscape is the old Priory of Blantyre, which, as

our readers are already aware, is situated on a rock of red sandstone

immediately opposite. Wordsworth, the poet, who visited this delightful

locality, truly remarks,—" It can scarcely be conceived what a grace the

Castle and Priory impart to each other." He further adds,—"The river Clyde

flows on, smooth and unruffled, below, seeming to my thoughts more in

harmony with the sober and stately images of former times, than if it had

roared over a rocky channel forcing its sound upon the ear."

Leaving the precincts of this magnificent and

awe-inspiring relic of bygone pomp and power, we now proceed by a shady

woodland path to visit the extensive gardens of Lord Douglas, which are

situated a short distance to the eastward. Having through the kindness of

a friend received an introduction to Mr. Turnbull, head-gardener to the

establishment, we are received with the most obliging courtesy by that

gentleman. Mr Turnbull, whose fame in his profession has, we believe,

extended even beyond the Tweed, may well be somewhat vain of the

flourishing condition of his numerous plants, indigenous and exotic.

Fruits and flowers are equally abundant, and superior in quality. Such

pines, grapes, and peaches, it has seldom been our fortune previously to

witness; while in the floral departments, things "rich and rare" seem to

be here collected from every country and clime. We are shown all

imaginable vegetable curiosities and rarities, such as pitcher plants,

sensitive plants, cacti of every possible shape, and many many others,

which, but to name, would puzzle a Linnæus. The collection of roses is

very extensive, and our visit fortunately happens at the very nick of time

to witness them in their hours of bloom. In one conservatory are no less

than two hundred distinct species of heaths, many of which are exquisitely

beautiful, and all are in the most healthy and luxuriant condition. Time

would fail us, however, were we to attempt to indicate even the leading

features of the bloomy wealth—the pansy, the pelargoniums, the

calceolarias, the fuchsias, and the cacti, which in greenhouse and on

lawn, are strewn profusely yet tastefully about. Suffice it to say, that

to any individual of taste, a visit to this place alone would far more

than repay a ramble to Bothwell. With many acknowledgments of his

kindness, we take leave of our friend Mr. Turnbull, and by a pleasant,

though somewhat tortuous route through the woods, return to Bothwell.

Feeling somewhat tired with our devious peregrinations

and the sultriness of the day, we rest in the village for an hour or two,

after which we pass over the river to Blantyre, and by the "last train" we

are in a brief space safely deposited at the terminus, whence some dozen

of hours ago we took our start.

|