|

WHILE the Earl of Mar was

thus busily engaged exciting a rebellion in the north, the government was no

less active in making preparations to meet it. Apprehensive of a general

rising in England, particularly in the west, where a spirit of disaffection

had often displayed itself, and to which the insurrection in Scotland was,

it was believed, intended as a diversion; the government, instead of

despatching troops to Scotland, posted the whole disposable force in the

disaffected districts, at convenient distances, by which disposition,

considerable bodies could be assembled together to assist each other in case

of need. The wisdom of this plan soon became apparent, as there can be no

doubt, that had an army been sent into Scotland to suppress the rebellion in

the north, an insurrection would have broken out in England, which might

have been fatal to the government.

To strengthen, however, the

military force in Scotland, the regiments of Forfar, Orrery, and Hill, were

recalled from Ireland. These arrived at Edinburgh about the 24th of August,

and were soon thereafter despatched along with other troops to the west,

under Major-general Wightman, for the purpose of securing the fords of the

Forth, and the pass of Stirling. These troops being upon the reduced

establishment, did not exceed 1,600 men, a force inadequate for the

protection of such an important post. Orders were, therefore, sent to the

Earl of Stair’s regiment of dragoons and two foot regiments, which lay in

the north of England, to march to the camp in the park of Stirling with all

expedition, and at the same time, Evans’s regiment of dragoons, and Clyton’s

and Wightman’s regiments of foot were recalled from Ireland.

During the time the camp was

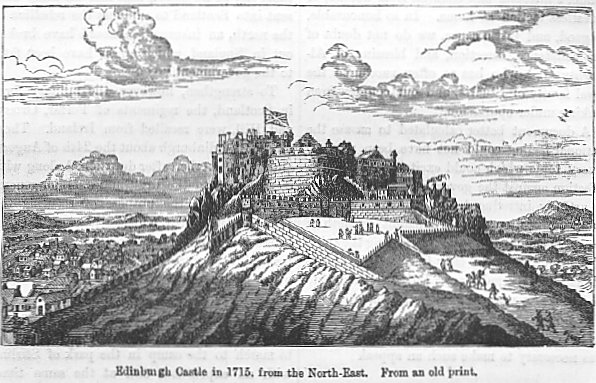

forming at Stirling, the friends of the Chevalier at Edinburgh formed the

daring project of seizing the castle of Edinburgh, the possession of which

would have been of vast importance to the Jacobite cause. Lord Drummond, a

Catholic, was at the head of this party, which consisted of about 90

gentlemen selected for the purpose, about one half of whom were Highlanders.

In the event of success, each of the adventurers was to receive £100

sterling and a commission in the army. To facilitate their design, they

employed one Arthur, who had formerly been an ensign in the Scotch guards,

to corrupt some of the soldiers in the garrison, and who by money and

promises of preferment induced a sergeant, a corporal, and two sentinels to

enter into the views of the conspirators. These engaged to attend at a

certain place upon the wall, on the north, near the Sally-port, in order to

assist the conspirators in their ascent. The latter had prepared a scaling

ladder made of ropes, capable of holding several men abreast, and had so

contrived it, that it could be drawn up through means of pulleys, by a small

rope which the soldiers were to fasten behind the wall. Having completed

their arrangements, they fixed on the 9th of September for the attempt,

being the day after the last detachment of the government troops quartered

in camp in St. Anne’s Yards, near Edinburgh, had set off for Stirling. But

the projectors of this well-concerted enterprise were doomed to lament its

failure when almost on the eve of completion.

Arthur, the officer who had

bribed the soldiers, having engaged his brother, a physician in Edinburgh,

in the Jacobite interest, let him into the secret of the design upon the

castle. Dr. Arthur, who appears to have been a man of a timorous

disposition, grew alarmed at this intelligence, and so deep had been the

impression made upon his mind while contemplating the probable consequences

of such a step, that on the day before the attempt his spirits became so

depressed as to attract the notice of his wife, who importuned him to inform

her of the cause. He complied, and his wife, without acquainting him, sent

an anonymous letter to Sir Adam Cockburn of Ormiston, Lord-Justice-Clerk,

acquainting him with the conspiracy. Cockburn received this letter at ten o’clock

at night, and sent it off with a letter from himself to Lieutenant-colonel

Stuart, the deputy-governor of the castle, who received the communication

shortly before eleven. Stuart lost no time in ordering the officers to

double their guards and make diligent rounds; but probably supposing that no

attempt would be made that night he went to bed after issuing these

instructions. In the meantime, the conspirators had assembled at a tavern

preparatory to their attempt, but unfortunately for its success they

lingered over their cups far beyond the time they had fixed upon for putting

their project into execution. In fact, they did not assemble at the bottom

of the wall till after the deputy-governor had issued his orders; but

ignorant of what had passed within the castle, they proceeded to tie the

rope, which had been let down by the soldiers, to the ladder. Unhappily for

the whole party, the hour for changing the sentinels had arrived, and while

the traitorous soldiers were in the act of drawing up the ladder, one

Lieutenant Lindsay, at the head of a party of fresh sentinels, came upon

them on his way to the sally-port. The soldiers, alarmed at the approach of

Lindsay’s party, immediately slipt the rope, one of them at the same time

discharging his piece at the assailants to divert suspicion from himself.

The noise which this occurrence produced told the conspirators that they

were discovered, on which they dispersed. A party of the town-guard which

the Lord Provost, at the request of the Lord-Justice-Clerk, had sent to

patrol about the castle, attracted by the firing, immediately rushed from

the West-Port, and repaired to the spot, but all the conspirators, with the

exception of four whom they secured, had escaped. These were one Captain

Maclean, an officer who had fought under Dundee at Killiecrankie, whom they

found lying on the ground much injured by a fall from the ladder or from a

precipice; Alexander Ramsay and George Boswell, writers in Edinburgh; and

one Lesly, who had been in the service of the same Duchess of Gordon who had

distinguished herself in the affair of the medal. This party picked up the

ladder and a quantity of muskets and carbines which the conspirators had

thrown away in their flight.

Such was the result of an

enterprise which had been matured with great judgment, and which would

probably have succeeded, but for the trifling circumstance above mentioned.

The capture of such an important fortress as the castle of Edinburgh, at

such a time, would have been of vast importance to the Jacobites, inasmuch

as it would not only have afforded them an abundant supply of military

stores, with which it was then well provided, and put them in possession of

a considerable sum of money, but would also have served as a rallying point

to the disaffected living to the south of the Forth, who only waited a

favourable opportunity to declare themselves. Besides giving them the

command of the city, the possession of the castle by a Jacobite force would

have compelled the commander of the government forces to withdraw the

greater part of his troops from Stirling, and leave that highly important

post exposed to the northern insurgents. Had the attempt succeeded, Lord

Drummond, the contriver of the design, was to have been made governor of the

castle, and notice of its capture was to have been announced to some of the

Jacobite partisans on the opposite coast of Fife, by firing three

cannon-shots from its battlements. On hearing the report of the guns, these

men were instantly to have communicated the intelligence to the Earl of Mar,

who was to hasten south with all his forces.

As the appointment of a

person of rank, influence, and talent, to the command of the army, destined

to oppose the Earl of Mar, was of great importance, the Duke of Argyle, who

had served with distinction abroad, and who had formerly acted as

commander-in-chief of the forces in Scotland, was pitched upon as

generalissimo of the army encamped at Stirling. Having received instructions

from his majesty on the 8th of September, he departed for Scotland the

following day, accompanied by some of the Scottish nobility, and other

persons of distinction, and arrived at Edinburgh on the 14th. About the same

time, the Earl of Sutherland, who had offered his services to raise the

clans in the northern Highlands, in support of the government, was sent down

from London to Leith in a ship of war, with orders to obtain a supply of

arms and ammunition from the governor of the castle of Edinburgh. He arrived

on the 21st of September, and after giving instructions for the shipment of

these supplies, departed for the north.

When the Duke of Argyle

reached Edinburgh, he found that Mar had made considerable progress in the

insurrection, and that the regular forces at Stirling were far inferior in

point of numbers to those of the Jacobite commander. He, therefore, on the

day he arrived in the capital, addressed a letter to the magistrates of

Glasgow, (who, on the first appearance of the insurrection, had offered, in

a letter to Lord Townshend, one of the secretaries of state, to raise 600

men in support of the government, at the expense of the city,) requesting

them to send forthwith 500 or 600 men to Stirling, under the command of such

officers as they should think fit to appoint, to join the forces stationed

there. In compliance with this demand, there were despatched to Stirling, on

the 17th, 18th, and 19th of September, three battalions, amounting to

between 600 and 700 men, under the nominal command of the Lord Provost, who

deputed the active part of his duties to Colonel Blackadder. On the arrival

of the first battalion, the duke addressed a second letter from Stirling to

the magistrates of Glasgow, thanking them for their promptitude, and

requesting them to send intimation, with the greatest despatch, to all the

friends of the government in the west, to assemble all the fencible forces

at Glasgow, and to hold them in readiness to march when required. In

connexion with these instructions, the duke, at the same time, wrote letters

of a similar import to the magistrates of all the well affected burghs, and

to private individuals who were known to be favourably disposed. The most

active measures were accordingly adopted in the south and west by the

friends of the government, and in a short time a sufficient force was raised

to keep the disaffected in these districts in check.

Meanwhile the Earl of Mar and

his friends were no less active in preparing for the campaign. Pursuant to

an arrangement with the Jacobite chiefs, General Gordon, an officer of great

bravery and experience, was despatched into the Highlands to raise the

north-western clans, with instructions either to join Mar with such forces

as he could collect at the fords of the Forth, or to march upon Glasgow by

Dumbarton. Having collected a body of between 4,000 and 5,000 men, chiefly

Macdonalds, Macleans, and Camerons, Gordon attempted to surprise

Fort-William, and succeeded so far as to carry by surprise some of the

outworks, sword in hand, in which were a lieutenant, sergeant, and 25 men;

but as the garrison made a determined resistance, he withdrew his men, and

marched towards Inverary. This route, it is said, was taken at the

suggestion of Campbell of Glendaruel, who, at the first meeting of the

Jacobites, had assured Mar and his friends that if the more northern clans

would take Argyleshire in their way to the south, their numbers would be

greatly increased by the Macleans, Macdonalds, Macdougalls, Macneills, and

the other Macs of that county, together with a great number of Campbells, of

the family and followers of the Earl of Breadalbane, Sir James Campbell of

Auchinbreck, and Sir Duncan Campbell of Lochnell; all of whom, he said,

would join in the insurrection, when they saw the other clans in that

country at hand to protect them against those in the interest of the Duke of

Argyle.

When the Earl of Islay,

brother to the Duke of Argyle, heard of General Gordon’s movements he

assembled about 2,500 men to prevent a rising of the clans in Argyle, and of

the disaffected branches of the name of Campbell. On arriving before

Inverary, General Gordon found the place protected by entrenchments which

the earl had thrown up. He did not venture on an attack, but contented

himself with encamping at the north-east side of the town, at nearly the

distance of a mile, where he continued some days without any hostile attempt

being made on either side. It was evidently contrary to Gordon’s plan to

hazard an action, his sole design in entering Argyleshire being to give an

opportunity to the Jacobite population of that district to join his

standard, which the keeping of such a large body of men locked up in

Inverary would greatly assist.

During the continuance before

Inverary of the "Black Camp," as General Gordon’s party was

denominated by the Campbells, the Earl of Islay and his men were kept in a

state of continual alarm from the most trifling causes. On one occasion an

amusing incident occurred, which excited the fears of the Campbells, and

showed how greatly they dreaded an attack. Some time before this occurrence,

a small body of horse from Kintyre had joined the earl: the men were

quartered in the town, but the horses were put out to graze on the east side

of the small river that runs past Inverary. The horses disliking their

quarters, took their departure one night in search of better pasture. They

sought their way along the shore for the purpose of crossing the river at

the lower end of the town. The trampling of their hoofs on the gravel being

heard at some distance by the garrison, the earl’s men were thrown into

the utmost consternation, as they had no doubt that the enemy was advancing

to attack them. As the horses were at full gallop, and advancing nearer

every moment, the noise increasing as they approached, nothing but terror

was to ho seen in every face. With trembling hands they seized their arms

and put themselves in a defensive posture to repel the attack, but they were

fortunately soon relieved from the panic they had been thrown into by some

of the horses which had passed the river approaching without riders; so that

"at last," says the narrator of this anecdote, "the whole was

found only to be a plot among the Kintyre horse to desert not to the enemy,

but to their own country; for ‘tis to be supposed the horses, as well as

their owners, were of very loyal principles."

Shortly after this event,

another occurrence took place, which terminated not quite so ridiculously as

the other. One night the sergeant on duty, when going his rounds at the

quarter of the town opposite to the place where the clans lay, happened to

make some mistake in the watchword. The sentinel on duty supposing the

sergeant and his party to be enemies, discharged his piece at them. The

earl, alarmed at the firing, immediately ordered the drums to beat to arms,

and in a short time the whole of his men were assembled on the castle-green,

where they were drawn up in battalions in regular order by torch or candle

light, the night being extremely dark. As soon as they were marshalled, the

earl gave them orders to fire in platoons towards the quarter whence they

supposed the enemy was approaching, and, accordingly, they opened a brisk

fire, which was kept up for a considerable time, by which several of their

own sentinels in returning from their posts were wounded. Whilst the

Campbells were thus employed upon the castle-green, several gentlemen, some

Bay general officers, who liked to fight "under covert," retired

to the square tower or castle of Inverary, from the windows of which they

issued their orders. When the earl found that he had no enemy to contend

with, he ordered his men to cease firing, and to continue all night under

arms. This humorous incident, however, was attended with good consequences

to the terrified Campbells, as it had the effect of relieving them from the

presence of the enemy. General Gordon, who had not the most distant

intention of entering the town, on hearing the close and regular firing from

the garrison, concluded that sonic forces had entered the town, to celebrate

whose arrival the firing had taken place, and alarmed for his own safety,

sounded a retreat towards Perth-shire before day-light.

No sooner, however, had the

clans left Inverary, than a detachment of the Earl of Breadalbane’s men,

to the number of about 500, entered the county under the command of Campbell

of Glenlyon. To expel them, the Earl of Islay sent a select body of about

700 men, in the direction of Loin, under the command of Colonel Campbell of

Fanab, an old and experienced officer, who came up with Glenlyon’s

detachment at Glenscheluch, a small village at the end of the lake called

Lochnell, in the mid division of Loin, about 20 miles distant from Inverary.

Both sides immediately prepared for battle, and to lighten themselves as

much as possible, the men threw off their plaids and other incumbrances.

Whilst both parties were standing gazing on each other with fury in their

looks, waiting for the signal to commence battle, a parley was proposed, in

consequence of which, a conference was held by the commanders half-way

between the lines. The result was, that the Breadalbane men, to spare the

effusion of the Campbell blood, agreed to lay down their arms on condition

of being allowed to march out of the country without disturbance. These

terms being communicated to both detachments, were approved of by a loud

shout of joy, and hostages were immediately exchanged on both sides for the

due performance of the articles. The Earl of Islay, on coming up with the

remainder of his forces, was dissatisfied with the terms of the

capitulation, as he considered that he had it in his power to cut off

Glenlyon’s party; but he was persuaded to accede to the articles, which

were accordingly honourably observed on both sides.

In the meantime, the Earl of

Mar had collected a considerable force, with which he marched, about the

middle of September, to Moulinearn, a small village in Athole, where he

proclaimed the Chevalier. On entering Athole, he was joined by 500 Atholemen,

under the Marquis of Tullibardine, and by the party of the Earl of

Breadalbane’s men, under Campbell of Glenlyon and Campbell of Glendaruel.

He was afterwards joined by the old earl himself, who, although he had, the

day preceding his arrival, procured an affidavit from a physician in Perth,

and the minister of the parish of Kenmore, of which he was patron,

certifying his total inability, from age, and a complication of diseases, to

comply with a mandate of the government requiring him to attend at

Edinburgh; yet, nevertheless, found himself able enough to take the field in

support of the Chevalier. Having received intelligence that the Earl of

Rothes, and some of the gentlemen of Fife, were advancing with 500 of the

militia of that county to seize Perth, he sent Colonel John Hay, brother to

the Earl of Kinnoul, with a detachment of 200 horse, to take possession of

that town; he accordingly entered it on the 14th of September, without

opposition, and there proclaimed the Chevalier. The provost made indeed a

demonstration of opposition by collecting between 300 and 400 men in the

market place; but Colonel Hay having been joined by a party of 150 men which

had been sent into the town a few days before by the Duke of Athole, the

provost dismissed his men. When the Earl of Rothes, who was advancing upon

Perth with a body of 500 men, heard of its capture, he retired to Leslie,

and sent notice of the event to the Duke of Argyle. The possession of Perth

was of importance to Mar in a double point of view, as it not only gave him

the command of the whole of Fife, in addition to the country north of the

Tay, but also inspired his friends with confidence. Accordingly, the

Chevalier was proclaimed at Aberdeen by the Earl Marischal; at Castle

Gordon, by the Marquis of Huntly; at Brechin, by the Earl of Panmure; at

Montrose, by the Earl of Southesk; and at Dundee, by Graham of Claverhouse,

who was afterwards created Viscount Dundee, by the Chevalier.

As Mar had no intention of

descending into the Lowlands himself without a considerable force, he

remained several days at Moulinearn waiting for the clans who had promised

to join him, and in the meantime directed Colonel Hay, whom, on the 18th of

September, he appointed governor of Perth, to retain possession of that town

at all hazards. He also directed him to tender to the inhabitants the oath

of allegiance to the Chevalier, and to expel from the town all persons who

refused to take the oath. After this purgation had been effected, Governor

Hay was ordered to appoint a free election of magistrates by poll, to open

all letters passing through the post-office, and to appoint a new postmaster

in whom he could have confidence. To support Hay in case of an attack, Mar

sent down a party of Robertsons, on the 22d, under the command of Alexander

Robertson of Strowan, their chief, known as the elector of Strowan.

At this time, Mar’s forces

did not probably exceed 3,000 men, but their number having been increased to

upwards of 5,000 within a few days thereafter, he marched down upon Perth,

which he entered on the 28th of September, on which day the Honourable James

Murray, second son of the Viscount Stormont, arrived at Perth with letters

from the Chevalier to the earl, giving him assurances of speedy and powerful

succour, and promises from the Chevalier, as was reported, of appearing

personally in Scotland in a short time. This gentleman had gone over to

France in the month of April preceding, to meet the Chevalier, who had

appointed him principal secretary for Scotland, and had lately landed at

Dover, whence he had travelled incognito overland to Edinburgh,

where, although well known, he escaped detection. After spending a few days

in Edinburgh, during which time he attended, it is said, several private

meetings of the friends of the Chevalier, he crossed the Frith in an open

boat at Newhaven, and landed at Burntisland, whence he proceeded to Perth.

The first operations of the

insurgents were marked by vigour and intrepidity. The seizure of Perth,

though by no means a brilliant affair, was almost as important as a victory

would have been at such a crisis, and another dashing exploit which a party

of the earl’s army performed a few days after his arrival at Perth, was

calculated to make an impression equally favourable to the Jacobite cause.

Before the Earl of Sutherland took his departure from Leith for Dunrobin

castle, to raise a force in the north, he arranged with the government for a

supply of arms, ammunition and military stores, which was to be furnished by

the governor of Edinburgh castle, and sent down to the north with as little

delay as possible. Accordingly, about the end of September, a vessel

belonging to Burntisland was freighted for that purpose, on board of which

were put about 400 stands of arms, and a considerable quantity of ammunition

and military stores. The vessel anchored in Leith roads, but was prevented

from passing down the Frith by a strong northeasterly wind, which,

continuing to blow very hard, induced the captain for security’s sake to

weigh anchor and stand over to Burntisland roads, on the opposite coast of

Fife, under the protection of the weather shore. The captain went on shore

at Burntisland, to visit his wife and family who resided in the town, and

the destination of the vessel, and the nature of her cargo being made known

to some persons in the Jacobite interest, information thereof was

immediately communicated by them to the Earl of Mar, who at once resolved to

send a detachment to Burntisland to seize the vessel. Accordingly, he

despatched on the evening of the 2d of October, a party of 400 horse, and

500 foot, from Perth to Burntisland, with instructions so to order their

march as not to enter the latter place till about midnight. To draw off the

attention of the Duke of Argyle from this expedition, Mar made a movement as

if he intended to march with all his forces upon Alva, in the neighbourhood

of Stirling, in consequence of which Argyle, who had received intelligence

of Mar’s supposed design, kept his men under arms the whole day in

expectation of an attack. Meanwhile, the party having reached their

destination, the foot entered Burntisland unperceived, and while the horse

surrounded the town to prevent any person from carrying the intelligence of

their arrival out of it, the foot seized all the boats in the harbour and

along the shore, to cut off all communication by sea. About 120 men were,

thereupon, sent off in some boats to board the ship, which they secured

without opposition. They at first attempted to bring the vessel into the

harbour, but were prevented by the state of the tide. They, however, lost no

time in discharging her cargo, and having pressed a number of carts and

horses from the neighbourhood into their service, the detachment set off

undisturbed for Perth with their booty, where they arrived without

molestation. Besides the arms and other warlike materials which they found

in the vessel, the detachment carried off 100 stands of arms from the town,

and between 30 and 40 more which they found in another ship. Emboldened by

the success of this enterprise, parties of the insurgents spread themselves

over Fife, took possession of all the towns on the north of the Frith of

Forth, from Burntisland to Fifeness, and prohibited all communication

between them and the opposite coast. The Earl of Rothes, who was quartered

at Leslie, was now obliged, for fear of being cut off, to retire to Stirling

under the protection of a detachment of horse and foot, which had been sent

from Stirling to support him, under the command of the Earl of Forfar, and

Colonel Ker.

Mar had not yet been joined

by any of the northern clans, nor by those under General Gordon; but on the

5th of October, about 500 of the Mackintoshes arrived under the command of

the Laird of Borlum, better known by the name of Brigadier Mackintosh, an

old and experienced soldier, who, as uncle of the chief, had placed himself

at the head of that clan in consequence of his nephew’s minority. This

clan had formerly sided with the revolution party; but, influenced by Borlum,

who was a zealous Jacobite, they were among the first to espouse the cause

of the Chevalier, and had seized upon Inverness before some of the other

clans had taken the field. On the following day the earl was also joined by

the Marquis of Huntly at the head of 500 horse and 2,000 foot, chiefly

Gordons; and on the 10th by the Earl Marischal with 300 horse, among whom

were many gentlemen, and 500 foot. These different accessions increased Mar’s

army to upwards of 8,000 men.

Mar ought now to have

instantly opened the campaign by advancing upon Stirling, and attacking the

Duke of Argyle, whose forces did not, at this time, amount to 2,000 men. In

his rear he had nothing to dread, as the Earl of Seaforth, who was advancing

to join him with a body of 3,000 foot and 600 home, had left a division of

2,000 of his men behind him to keep the Earl of Sutherland, and the other

friends of the government in the northern Highlands, in check As the whole

of the towns on the eastern coast from Burntisland to Inverness were in

possession of his detachments, and as there was not a single hostile party

along the whole of that extensive stretch, no obstacle could have occurred,

had he marched south, to prevent him from obtaining a regular supply of

provisions for his army and such warlike stores as might reach any of these

ports from France. One French vessel had already safely landed a supply of

arms and ammunition in a northern port, and another during Mar’s stay at

Perth boldly sailed up the Frith of Forth, in presence of some English ships

of war, and entered the harbour of Burntisland with a fresh supply. But

though personally brave, Mar was deficient in military genius, and was

altogether devoid of that promptitude of action by which Montrose and Dundee

were distinguished. Instead, therefore, of attempting at once to strike a

decisive blow at Argyle, the insurgent general lingered at Perth upwards of

a month. This error, however, might have been repaired had he not committed

a more fatal one by detaching a considerable part of his army, including the

Macintoshes, who were the best armed of his forces, at the solicitation of a

few English Jacobites, who, having taken up arms in the north of England,

craved his support.

About the period of Mar’s

departure for Scotland, the government had obtained information of a

dangerous conspiracy in England in favour of the Chevalier, in consequence

of which the titular Duke of Powis was committed to the Tower, and Lords

Lansdowne and Dupplin were arrested, as implicated in the conspiracy, and a

warrant was issued for the apprehension of the Earl of Jersey. At the same

time, a message from the king was sent to the house of commons, informing

them that his majesty had given orders for the apprehension of Sir William

Wyndham, Mr. Thomas Forster, junior, member for the county of

Northumberland, and other members of the lower house, as being engaged in a

design to support an invasion of the kingdom. Sir William Wyndham was

accordingly apprehended, and committed to the Tower, but Mr. Forster having

been apprised of the arrival of a messenger at Durham with the warrant for

his apprehension, avoided him, and joined the Earl of Derwentwater, a young

Catholic nobleman, against whom a similar warrant had been issued. Tired of

shifting from place to place, they convened a meeting of their friends in

Northumberland to consult as to the course they should pursue; it was

resolved immediately to take up arms in support of the Chevalier. In

pursuance of a resolution entered into, about 60 horsemen, mostly gentlemen,

and some attendants, met on Thursday the 6th of October, at a place called

Greenrig, whence, after some consultation, they marched to Plainfield, a

place on the river Coquet, where they were joined by a few adherents. From

Plainfield they departed for Rothbuxy, a small market town, where they took

up their quarters for the night.

Next morning, their numbers

still increasing, they advanced to Warkworth, where they were joined by Lord

Widdrington, with 30 horse. Mr. Forster was now appointed to the command of

this force, not on account of his military abilities, for he had none, but

because he was a Protestant, and therefore less objectionable to the

high-church party than the Earl of Derwentwater, who, in the absence of a

regularly bred commander, should, on account of his rank, have been named to

the chief command. On Sunday morning, Mr. Forster sent Mr. Buxton, a

clergyman of Derbyshire, who acted as chaplain to the insurgent party, to

the parson of Warkworth, with orders to pray for the Chevalier by name as

king, and to introduce into the Litany the name of Mary, the queen-mother,

and all the dutiful branches of the royal family, and omit the names of King

George, and the prince and princess. The minister of the parish wisely

declined to obey these orders, and for his own safety retired to Newcastle.

The parishioners, however, were not deprived of divine service, as Mr.

Buxton, on the refusal of the parson to officiate as directed, entered the

church, and performed in his stead with considerable effect.

On Monday the 10th of

October, Mr. Forster was joined by 40 horse from the Scottish border, on

which day he openly proclaimed the Chevalier. This small party remained at

Warkworth till the 14th, when they proceeded to Alnwick, where they were

joined by many of their friends, and thence marched to Morpeth. At Eelton

bridge they were reinforced by another party of Scottish horse to the number

of 70, chiefly gentlemen from the border, so that on entering Morpeth their

force amounted to 300 horse. In the course of his march Forster had numerous

offers of service from the country people, which, however, he was obliged to

decline from the want of arms; but he promised to avail himself of them as

soon as he had provided himself with arms and ammunition, which he expected

to find in Newcastle, whither he intended to proceed.

In connection with these

movements, Launcelot Errington, a Newcastle shipmaster, undertook to

surprise Holy Island, which was guarded by a few soldiers, exchanged weekly

from the garrison of Berwick. In a military point of view, the possession of

such an insignificant post was of little importance, but it was considered

by the Jacobites as useful for making signals to such French vessels as

might appear off the Northumberland coast with supplies for the insurgents.

Errington, it appears, was known to the garrison, as he had been in the

habit of visiting the island on business; and having arrived off the island

on the 10th of October, he was allowed to enter the port, no suspicions

being entertained of his design. Pursuant to the plan he had formed for

surprising the castle, he invited the greater part of the garrison to visit

his vessel, and having got them on board, he and the party which accompanied

him left the vessel, and took possession of the castle without opposition.

Errington endeavoured to apprise his friends at Warkworth of his success by

signals, but these were not observed, and the place was retaken the

following day by a detachment of 30 men from the garrison of Berwick, and a

party of 50 of the inhabitants of the town, who, crossing the sands at low

water, entered the island, and carried the fort sword in hand. Errington, in

attempting to escape, received a shot in the thigh, and being captured, was

carried prisoner to Berwick; whence he had the good fortune to make his

escape in disguise. The possession of Newcastle, where the Jacobite interest

was very powerful, was the first object of the Northumberland insurgents;

but they were frustrated in their design by the vigilance of the

magistrates. Having first secured all suspected persons, the magistrates

walled up all the gates with stone and lime, except the Brampton gate, on

which they placed two pieces of cannon, An association of the well-affected

inhabitants was formed for the defence of the town, and the churchmen and

dissenters, laying aside their antipathies for a time, enrolled themselves

as volunteers. 700 of these were immediately armed by the magistrates. The

keelmen also, who were chiefly dissenters, offered to furnish a similar

number of men to defend that town; but their services were not required, as

two successive reinforcements of regular troops from Yorkshire arrived on

the 9th and 12th of October. When the insurgents received intelligence of

the state of affairs at Newcastle, they retired to Hexham, having a few days

before sent an express to the Earl of Mar for a reinforcement of foot.

The news of the rising under

Mr. Forster having been communicated to the Marquis of Tweeddale, Lord

Lieutenant of Haddingtonshire, his lordship called a meeting of his deputy

lieutenants at Haddington early in October, and at the same time issued

instructions to them to put the laws in execution against

"papists" and other suspected persons, by binding them over to

keep the peace, and by seizing their arms and horses in terms of a late act

of parliament. In pursuance of this order, Mr. Hepburn of Humbie, and Dr.

Sinclair of Hermandston, two of the deputy lieutenants, resolved to go the

morning after the instructions were issued, to the house of Mr. Hepburn of

Keith, a zealous Jacobite, against whom they appear to have entertained

hostile feelings. Dr. Sinclair accordingly appeared next morning with a

party of armed men at the place where Hepburn of Humbie had agreed to meet

him; but as the latter did not appear at the appointed hour, the doctor

proceeded towards Keith with his attendants. On their way to Keith, Hepburn

enjoined his party, in case of resistance, not to fire till they should be

first fired at by Mr. Hepburn of Keith or his party; and on arriving near

the house he reiterated these instructions. When the arrival of Sinclair and

his party was announced to Mr. Hepburn of Keith, the latter at once

suspecting the cause, immediately demanded inspection of the doctor’s

orders. Sinclair, thereupon, sent forward a servant with the Marquis of

Tweeddale’s commission, who, finding the gates shut, offered to show the

commission to Hepburn at the dining-room window. On being informed of the

nature of the commission, Hepburn signified the utmost contempt at it, and

furiously exclaiming "God damn the doctor and the marquis both,"

disappeared. The servant thinking that Mr. Hepburn had retired for a time to

consult with his friends before inspecting the commission, remained before

the inner gate waiting for his return. But instead of coming back to receive

the commission, Hepburn and his friends immediately mounted their horses and

sallied out, Hepburn discharging a pistol at the servant, which wounded him

in two places. Old Keith then rode up to the doctor, who was standing near

the outer gate, and after firing another pistol at him, attacked him sword

in hand and wounded him in the head. Sinclair’s party, in terms of their

instructions, immediately returned the fire, and Mr. Hepburn’s younger son

was unfortunately killed on the spot. Hepburn and his party, disconcerted by

this event, instantly galloped off towards the Borders and joined the

Jacobite standard. The death of young Hepburn, who was the first person that

fell in the insurrection of 1715, highly incensed the Jacobites, who longed

for an opportunity, which was soon afforded them, of punishing its author,

Dr. Sinclair.

Whilst Mr. Forster was thus

employed in Northumberland, the Earl of Kenmure, who had received a

commission from the Earl of Mar to raise the Jacobites in the south of

Scotland, was assembling his friends on the Scottish border. Early in

October he had held private meetings with some of them, at which it had been

resolved to make an attempt upon Dumfries, expecting to surprise it before

the friends of the government there should be aware of their design; but the

magistrates got timely warning. Lord Kenmure first appeared in arms, at the

head of 150 horse, on the 11th of October at Moffat, where he proclaimed the

Chevalier, on the evening of which day he was joined by the Earl of Wintoun

and 14 attendants. Next day he proceeded to Lochmaben, where he also

proclaimed "the Pretender." Alarmed at his approach, the

magistrates of Dumfries ordered the drums to beat to arms, and for several

days the town exhibited a scene of activity and military bustle perfectly

ludicrous, when the trifling force with which it was threatened is

considered. Kenmure advanced within two miles of the town, but being

informed of the preparations which had been made to receive him, he returned

to Lochmaben. He thereupon marched to Ecclefechan, where he was joined by

Sir Patrick Maxwell of Springkell, with 14 horsemen, and thence to Langholm,

and afterwards to Hawick, where he proclaimed the Chevalier. On the 17th of

October, Kenmure marched to Jedburgh, with the intention of proceeding to

Kelso, and there also proclaimed the prince; but learning that Kelso was

protected by a party under the command of Sir William Bennet of Grubbet, he

crossed the Border with the design of forming a junction with Forster.

We must now direct attention

to the measures taken by the Earl of Mar in compliance with the request of

Mr. Forster and his friends to send them a body of foot. As Mar had not

resolution to attempt the passage of the Forth, which, with the forces under

his command, he could have easily effected, he had no other way of

reinforcing the English Jacobites, than by attempting to transport a part of

his army across the Frith. As there were several English men-of-war in the

Frith, the idea of sending a body of 2,000 men across such an extensive arm

(if the sea appeared chimerical ; yet, nevertheless, Mar resolved upon this

bold and hazardous attempt.

To command this adventurous

expedition, the Jacobite general pitched upon Old Borluin, as Brigadier

Mackintosh was familiarly called, who readily undertook, with the assistance

of the Earl of Panmure, and other able officers, to perform a task which few

men, even of experience, would have undertaken without a grudge. For this

hazardous service, a picked body of 2,500 men was selected, consisting of

the whole of the Mackintoshes, and the greater part of Mar’s own regiment,

and of the regiments of the Earl of Strathmore, Lord Nairne, Lord Charles

Murray, and Drummond of Logic Drummond. To escape the men-of-war, which were

stationed between Leith and Burntisland, it was arranged that the expedition

should embark at Crail, Pittenweem, and Elie, three small towns near the

mouth of the Frith, whither the troops were to proceed with the utmost

secrecy and expedition by the most unfrequented ways through the interior of

Fife. At the same time, to amuse the ships of war, it was concerted that

another small and select body should openly march across the country to

Burntisland, seize upon the boats in the harbour, and make preparations as

if they intended to cross the Frith. With remarkable foresight, Mar gave

orders that the expedition should embark with the flowing of the tide, that

in case of detection, the ships of war should be obstructed by it in their

pursuit down the Frith.

Accordingly, on the 9th or

10th of October, both detachments left Perth escorted by a body of horse

under the command of Sir John Erskine of Alva, the Master of Sinclair, and

Sir James Sharp, grandson of Archbishop Sharp of St. Andrews; and whilst the

main body proceeded in a south-easterly direction, through the district of

Fife bordering upon the Tay, so as to pass unobserved by the men-of-war, the

other division marched directly across the country to Burntisland, where

they made a feint as if preparing to embark in presence of the ships of war

which then lay at anchor in Leith Roads. When the commanders of these

vessels observed the motions of the insurgents, they manned their boats and

despatched them across to attack them should they venture out to sea, and

slipping their cables they stood over with their vessels to the Fife shore

to support their boats. As the boats and ships approached, the insurgents,

who had already partly embarked, returned on shore; and those on land

proceeded to erect a battery, as if for the purpose of covering the

embarkation. An interchange of shots then took place without damage on

either side, till night put an end to hostilities. In the meantime,

Brigadier Mackintosh had arrived at the different stations fixed for his

embarkation, at the distance of nearly 20 miles from the ships of war, and

was actively engaged in shipping his men in boats which had been previously

secured for their reception by his friends in these quarters. The first

division crossed the same night, being Wednesday the 12th of October, and

the second followed next morning. When almost half across the channel,

which, between the place of embarkation and the opposite coast, is about 16

or 17 miles broad, the fleet of boats was descried from the top-masts of the

men-of-war, and the commanders then perceived, for the first time, the

deception which had been so successfully practised upon them by the

detachment at Burntisland. Unfortunately, at the time they made this

discovery, both wind and tide were against them; but they sent out their

boats fully manned, which succeeded in capturing only two boats with 40 men,

who were carried into Leith, and committed to jail. As soon as the tide

changed, the men-of-war proceeded down the Frith, in pursuit, but they came

too late, and the whole of the boats, with the exception of eight, (which

being far behind, took refuge in the Isle of May, to avoid capture,) reached

the opposite coast in perfect safety, and disembarked their men at Gullane,

North Berwick, Aberlady, and places adjacent. The number carried over

amounted to about 1,600. Those who were driven into the Isle of May,

amounting to 200, after remaining therein a day or two, regained the Fife

coast, and returned to the camp at Perth.

The news of Mackintosh’s

landing occasioned a dreadful consternation at Edinburgh., where the friends

of the government, astonished at the boldness of the enterprise, and the

extraordinary success which had attended it, once conjectured that the

brigadier would march directly upon the capital, where he had many friends,

and from which he was only 16 miles distant. As the city was at this time

wholly unprovided with the means of defence, Campbell, the provost, a warm

partisan of the government, adopted the most active measures for putting it

in a defensive state. The well affected among the citizens formed themselves

into a body for its defence, under the name of the Associate Volunteers, and

these, with the city guards and trained bands, had different posts assigned

them, which they guarded with great care and vigilance. Even the ministers

of the city, to show an example to the lay citizens, joined the ranks of the

armed volunteers. The provost, at the same time, sent an express to the Duke

of Argyle, requesting him to send, without delay, a detachment of regular

troops to support the citizens.

After the brigadier had

mustered his men, he marched to Haddington, in which he took up his quarters

for the night to refresh his troops, and wait for the remainder of his

detachment, which he expected would follow. According to Mackintosh’s

instructions, he should have marched directly for England, to join the

insurgents in Northumberland, but having received intelligence of the

consternation which prevailed at Edinburgh, and urged, it is believed, by

pressing solicitations from some of the Jacobite inhabitants to advance upon

the capital, as well as lured by the eclat which its capture would confer

upon his arms, and the obvious advantages which would thence ensue, he

marched rapidly towards Edinburgh the following morning. He arrived in the

evening of the same day, Friday 14th October, at Jock’s lodge, about a

mile from the city, where, being informed of the measures which had been

taken to defend it, and that the fluke of Argyle was hourly expected from

Stirling with a reinforcement, he immediately halted, and called a council

of war. After a short consultation, they resolved, in the meantime, to take

possession of Leith. Mackintosh, accordingly, turning off his men to the

right, marched into the town without opposition. He immediately released

from jail the 40 men who had been taken prisoners by the boats of the

men-of-war, and seized a considerable quantity of brandy and provisions,

which he found in the custom-house. He then took possession of and quartered

his men in the citadel which had been built by Oliver Cromwell. This fort,

which was of a square form, with four demi-bastions, and surrounded by a

large dry ditch, was now in a very dismantled state, though all the

outworks, with the exception of the gates, were entire. Within the walls

were several houses, built for the convenience of sea bathing, and which

served the new occupants in lieu of barracks. To supply the want of gates,

Mackintosh formed barricades of beams, planks, and of carts filled with

earth, stone, and other materials, and seizing six or eight pieces of cannon

which he found in some vessels in the harbour, he planted two of them at the

north end of the drawbridge, and the remainder upon the ramparts of the

citadel Within a few hours, therefore, after he had entered Leith,

Mackintosh was fully prepared to withstand a siege, should the Duke of

Argyle venture to attack him.

Whilst Mackintosh was in full

march upon the capital from the east, the Duke of Argyle was advancing upon

it with greater rapidity from the west, at the head of 400 dragoons and 200

foot, mounted, for the sake of greater expedition, upon farm-horses. Ho

entered the city by the west port about ten o’clock at night, and was

joined by the horse militia of Lothian and the Merse with a good many

volunteers, both horse and foot, who, with the Marquis of Tweeddale, Lord

Belhaven, and others, had retired into Edinburgh on the approach of the

insurgents. These, with the addition of the city guard and volunteers,

increased his force to nearly 1,200 men. With this body the duke marched

down towards Leith next morning, Saturday, 15th October; but before he

reached the town many of the "brave gentlemen volunteers," whose

enthusiasm had cooled while contemplating the probable consequences of

encountering in deadly strife the determined band to which they were to be

opposed, slunk out of the ranks and retired to their homes. On arriving near

the citadel, Argyle posted the dragoons and foot on opposite sides, and

along with Generals Evans and Wightman, proceeded to reconnoitre the fort on

the sea side. Thereafter he sent in a summons to the citadel requiring the

rebels to surrender under the pain of high treason, and declaring that if

they obliged him to employ cannon to force them, and killed any of his men

in resisting him, he would give them no quarter. To this message the laird

of Kynnacbin, a gentleman of Athole, returned this resolute answer, that as

to surrendering they did not understand the word, which could therefore only

excite laughter — that if his grace thought he was able to make an

assault, he might try, but he would find that they were fully prepared to

meet it; and as to quarter they were resolved, in case of attack, neither to

take nor to give any.

This answer was followed by a

discharge from the cannon on the ramparts, which made Argyle soon perceive

the mistake he had committed in advancing without cannon. Had his force been

equal and even numerically superior to that of Mackintosh, he could not have

ventured without almost certain destruction, to have carried the citadel

sword in hand, as he found that before his men could reach the foot of the

wall or the barricaded positions, they would probably have been exposed to

five rounds from the besieged, which, at a moderate computation, would have

cut off one half of his men. His cavalry, besides, on account of the nature

of the ground, could have been of little use in an assault; and as, under

such circumstances, an attack was considered impracticable, the duke retired

to Edinburgh in the evening to make the necessary preparations for a siege.

While deliberating on the expediency of making an attack, some of the

volunteers were very zealous for it, but on being informed that it belonged

to them as volunteers to lead the way, they heartily approved of the duke’s

proposal to defer the attempt till a more seasonable opportunity.

Had the Earl of Mar been

apprised in due time of Mackintosh’s advance upon Edinburgh, and of the

Duke of Argyle’s departure from Stirling, he would probably have marched

towards the latter place, and might have crossed the Forth above the bridge

of Stirling, without any very serious opposition from the small force

stationed in the neighbourhood; but he received the intelligence of the

brigadier’s movement too late to make it available, had he been inclined;

moreover it appears that he had resolved not to cross the Forth till joined

by General Gordon’s detachment.

On returning to Edinburgh the

Duke of Argyle gave orders for the removal of some pieces of cannon from the

castle to Leith, with the intention of making an assault upon the citadel

the following morning with the whole of his force, including the dragoons,

which he had resolved to dismount for the occasion. But he was saved the

necessity of such a hazardous attempt, the insurgents evacuating the place

the same night. Old Borlum, seeing no chance of obtaining possession of

Edinburgh, and considering that the occupation of the citadel, even if

tenable, was not of sufficient importance to employ such a large body of men

in its defence, had resolved, shortly after the departure of the duke, to

abandon the place, and to retrace his steps without delay, and with all the

secrecy in his power. Two hours before his departure, he sent a boat across

the Frith with despatches to the Earl of Mar, giving him a detail of his

proceedings since his landing, and informing him of his intention to retire.

To deceive the men-of-war which lay at anchor in the Roads, he caused a shot

to be fired after the boat, which had the desired effect of making the

officers in command of the ships think the boat had some friends of the

government on board, and thus allowing her to pursue her course without

obstruction.

At nine o’clock at night,

every thing being in readiness, Mackintosh, favoured by the darkness of the

night and low water, left the citadel secretly, and pursuing his course

along the beach, crossed, without observation, the small rivulet which runs

through the harbour at low water, and which was then about knee deep, and

passing the point of the pier, pursued his route south-eastward along the

sands of Leith. At his departure, Mackintosh was obliged to leave about 40

men behind him, who having made too free with the brandy which had been

found in the custom—house, were not in a condition to march. These, with

some stragglers who lagged behind, were afterwards taken prisoners by a

detachment of Argyle’s forces, which also captured some baggage and

ammunition.

The Highlanders continued

their march during the night, and arrived at two o’clock on the morning of

Sunday, the 16th of October, at Seaton House, the seat of the Earl of

Wintoun, who had already joined the Viscount Kenmure. Here, during the day,

they were joined by a small party of their friends, who had crossed the

Frith some time after the body which marched to Leith had landed, and who,

from having disembarked farther to the eastward, had not been able to reach

their companions before their departure for the capital. As soon as the Duke

of Argyle heard of Mackintosh’s retreat, and that he had taken up a

position in Seaton House, which was encompassed by a very strong and high

stone wall, he resolved to follow and besiege him in his new quarters. But

the duke was prevented from carrying this design into execution by receiving

intelligence that Mar was advancing upon Stirling with the intention of

crossing the Forth.

Being apprised by the receipt

of Mackintosh’s despatch from Leith, of the Brigadier’s design to march

to the south, Mar had resolved, with the view principally of facilitating

his retreat from Leith, to make a movement upon Stirling, and thereby induce

the Duke of Argyle to return to the camp in the Park with the troops which

he had carried to Edinburgh. Mar, accordingly, left Perth on Monday the 17th

of October, and General Witham, the commander of the royalist forces at

Stirling in Argyle’s absence, having on the previous day received notice

of Mar’s intention, immediately sent an express to the duke, begging him

to return to Stirling immediately, and bring back the forces he had taken

with him to Edinburgh. The express reached Edinburgh at an early hour on

Monday morning, and the duke immediately left Edinburgh for Stirling,

leaving behind him only 100 dragoons and 150 foot under General Wightman. On

arriving at Stirling that night he was informed that Mar was to be at

Dunblane next morning with his whole army, amounting to nearly 10,000 men.

The arrival of his Grace was most opportune, for Mar had in fact advanced

the same evening, with all his horse, to Dunblane, little more than six

miles from Stirling, and his foot were only a short way off from the latter

place. Whether Mar would have really attempted the passage of the Forth but

for the intelligence he received next morning, is very problematical; but

having been informed early on Tuesday of the duke’s return, and of the

arrival of Evans’s regiment of dragoons from Ireland, he resolved to

return to Perth. In a letter which he wrote to Mr. Forster from Perth on the

21st of October, after alluding to the information he had received, he gives

as an additional reason for this determination, that he had left Perth

before provisions could be got ready for his army, and that he found all the

country about Stirling, where he meant to pass the Forth, so entirely

exhausted by the enemy that he could find nothing to subsist upon. Besides,

from a letter he had received from General Gordon, he found the latter could

not possibly join him that week, and he could not think of passing the

Forth, under the circumstances detailed, till joined by him. Under these

difficulties, and having accomplished one of the objects of his march, by

withdrawing the Duke of Argyle from the pursuit of his friends in Lothian,

he had thought fit, he observes, to march back from Dunblane to Auchterarder,

and thence back to Perth, there to wait for Gordon and the Earl of Seaforth.

Mackintosh, in expectation

probably of an answer to his despatch from Leith, appeared to be in no hurry

to leave Seaton House, where his men fared sumptuously upon the best that

the neighbourhood could afford. As rJl communication was cut off between him

and the capital by the 100 dragoons which Argyle had left behind, and a

party of 300 gentlemen-volunteers under the command of the Earl of Rothes,

who patrolled in the neighbourhood of Seaton House, Mackintosh was in

complete ignorance of Argyle’s departure from the capital, and of Mar’s

march. This was fortunate, as it seems probable that had the Brigadier been

aware of these circumstances, he would have again advanced upon the capital,

and might have captured it. During the three days that Mackintosh lay in

Seaton House, no attempt was, of course, made to dislodge him from his

position, but he was subjected to some petty annoyances by the volunteers

and dragoons, between whom and the Highlanders some occasional shots were

interchanged without damage on either side. Having deviated from the line of

instructions, Mackintosh appears to have been anxious, before proceeding

south, to receive from Mar such new or additional directions as a change of

circumstances might require. Mar lost no time in replying to Borlum’s

communication, and on Tuesday the 18th of October, Borlum received a

despatch desiring him to march immediately towards England, and form a

junction near the borders with the English Jacobite forces under Mr.

Forster, and those of the south of Scotland under Lord Kenmure. On the same

day, Mackintosh received a despatch from Mr. Forster, requesting him to meet

him without delay at Kelso or Coldstream.

To give effect to these

instructions, Mackintosh left Seaton House next morning, and proceeded

across the country towards Longformacus, which he reached that night. Doctor

Sinclair, the proprietor of Hermandston House, had incurred the Brigadier’s

displeasure by his treatment of the laid of Keith, to revenge which he

threatened to burn Sinclair's mansion in passing it on his way south, but he

was persuaded not to carry his threat into execution. He, however, ordered

his soldiers to plunder the house, a mandate which they obeyed with the

utmost alacrity. When Major-general Wightman heard of Mackintosh’s

departure, he marched from Edinburgh with some dragoons, militia and

volunteers, and took possession of Seaton House. After demolishing the wall

which surrounded it, he returned to Edinburgh in the evening, carrying along

with him some Highlanders who had lagged behind or deserted from Mackintosh

on his march.

Mackintosh took up his

quarters at Longformacus during the night, and continued his march next

morning to Dunse, where he arrived during the day and proclaimed the

Chevalier. Here Mackintosh halted two days, and on the morning of Saturday

the 224 of October, set out on his march to Kelso, the appointed place of

rendezvous, whither the Northumbrian forces under Forster were marching the

same day. Sir William Bennet of Grubbet and his friends hearing of the

approach of these two bodies, left the town the preceding .night, and, after

dismissing their followers, retired to Edinburgh. The united forces of

Forster and Kenmure entered Kelso about one o’clock on Saturday. The

Highlanders had not then arrived, but hearing that they were not far off,

the Scottish cavalry, to mark their respect for the bravery the Highlanders

had shown in crossing the Frith, marched out as far as Ednam bridge to meet

them, and accompanied them into the town about three o’clock in the

afternoon, amidst the martial sounds of bagpipes. The forces under

Mackintosh now amounted to 1,400 foot and 600 horse; but a third of the

latter consisted of menial servants.

The following day, being

Sunday, was entirely devoted by the Jacobites to religious duties. Patten,

the historian of the insurrection, an episcopal minister and one of their

chaplains, in terms of instructions from Lord Kenmure, who had the command

of the troops while in Scotland, preached in the morning in the great church

of Kelso, formerly the abbey of David I., to a mixed congregation of

Catholics, Presbyterians and Episcopalians, from Deuteronomy xxi. 17.

"The right of the first born is his."

["All the lords that

were Protestants, with a vast multitude of people, attended: It was very

agreeable to see how decently and reverently the very common Highlanders

behaved, and answered the responses according to the Rubrick, to the shame

of many that pretend to more polite breeding." —Patten, p. 40.

Patteu, p. 49.]

The prayers on this occasion

were read by Mr. Buxton, formerly alluded to. In the afternoon Mr. William

Irvine, an old Scottish Episcopalian minister, chaplain to the Earl of

Carnwath, read prayers, and delivered a sermon full of exhortations to his

hearers to be zealous and steady in the cause of the Chevalier. This

discourse, he afterwards told his colleague, Mr. Patten, he had formerly

preached in the Highlands about twenty-six years before, in presence of Lord

Viscount Dundee and his army.

Next morning the Highlanders

were drawn up in the church-yard, and thence marched to the market-cross

with colours flying, drums beating, and bagpipes playing, when the Chevalier

was proclaimed by Seaton of Barnes, who claimed the vacant title of Earl of

Dunfermline. After finishing the proclamation, he read the manifesto quoted

in the conclusion of last chapter, at the end of which the people with loud

acclamations shouted, "No union! no malt-tax! no salt-tax !"

The insurgents remained three

days in Kelso, chiefly occupied in searching for arms and plundering the

houses of some of the loyalists in the neighbourhood. They took possession

of some pieces of cannon which had been brought by Sir William Bennet from

Hume castle for the defence of the town, and which had formerly been

employed to protect that ancient stronghold against the attacks of the

English. They also seized some broad-swords which they found in the church,

and a small quantity of gunpowder. Whilst at Kelso, Mackintosh seized the

public revenue, as was his uniform custom in every town through which he

passed.

During their stay at Kelso,

the insurgents seem to have come to no determination as to future

operations; but the arrival of General Carpenter with three regiments of

dragoons, and a regiment of foot, at Wooler, forced them to resolve upon

something decisive. Lord Kenmure, thereupon, called a council of war to

deliberate upon the course to be pursued. According to the opinions of the

principal officers, there were three ways of proceeding. The first, which

was strongly urged by the Earl of Wintoun, was to march into the west of

Scotland, to reduce Dumfries and Glasgow, and thereafter to form a junction

with the western clans, under General Gordon, to open a communication with

the Earl of Mar, and threaten the Duke of Argyle’s rear. The second was to

give battle immediately to General Carpenter. who had scarcely 1,000 men

under him, the greater part of whom consisted of newly-raised levies, who

had never seen any service. This plan was supported by Mackintosh, who was

so intent upon it, that, sticking his pike in the ground, he declared that

he would not stir, but would wait for General Carpenter, and fight him, as

he was sure there would be no difficulty in beating him. The last plan,

which was that of the Northumberland gentlemen, was to march directly

through Cumberland and Westmoreland into Lancashire, where the Jacobite

interest was very powerful, and where they expected to be joined by great

numbers of the people. Old Borlum was strongly opposed to this view, and

pointed out the risk which they would run, if met by an opposing force,

which they might calculate upon, while General Carpenter was left in their

rear. He contended, that if they succeeded in defeating Carpenter, they

would soon be able to fight any other troops,— that if Carpenter should

beat them, they had already advanced far enough, and that they would be

better able, in the event of a reverse, to shift for themselves in Scotland

than in England.

Either of the two

first-mentioned plans was far preferable to the last, even had the troops

been disposed to adopt it; but the aversion of the Highlanders to a campaign

in England was almost insuperable; and nothing could mark more strongly the

fatuity of the Northumberland Jacobites, than to insist, under these

circumstances, upon marching into England. But they pertinaciously adhered

to their opinion, and, by doing so, may be truly said to have ruined the

cause which they had combined to support. As the comparatively small body of

troops under Argyle was the only force in Scotland from which the insurgents

had anything to dread, their whole attention should have been directed in

the first place to that body, which could not have withstood the combined

attacks of the forces which the rebels had in the field, amounting to about

16,000 men. The Duke of Argyle must have been compelled, had the three

divisions of the insurgent army made a simultaneous movement upon Stirling,

to have hazarded a battle, and the result would very probably have been

disastrous to his army. Had such an event occurred, the insurgents would

have immediately become masters of the whole of Scotland, and would soon

have been in a condition to have carried the war into England with every

hope of success.

Amidst the confusion and

perplexity occasioned by these differences of opinion, a sort of medium

course was in the mean time resolved upon, till the chiefs of the army

should reconcile their divisions. The plan agreed upon was, that they should

to avoid an immediate encounter with General Carpenter, decamp from Kelso,

and proceed along the border in a south-westerly direction towards Jedburgh:

accordingly, on Thursday the 27th of October, the insurgents proceeded on

their march. The disagreement which had taken place had cooled their

military fervour, and a feeling of dread, at the idea of being attacked by

Carpenter’s force, soon began to display itself. Twice, on the march to

Jedburgh, were they thrown into a state of alarm, approaching to terror, by

mistaking a party of their own men for the troops of General Carpenter.

Instead of advancing upon

Jedburgh, as they supposed Carpenter would have done, the insurgents

ascertained that he had taken a different direction in entering Scotland,

and that from their relative positions, they were considerably in advance of

him in the proposed route into England. The English officers thereupon again

urged their views in council, and insisted upon them with such earnestness,

that Old Borlum was induced, though with great reluctance, and not till

after very high words had been exchanged, to yield. Preparatory to crossing

the Borders, they despatched one Captain Hunter (who, from following the

profession of a horse-stealer on the Borders, was well acquainted with the

neighbouring country,) across the bills, to provide quarters for the army in

North Tynedale; but he had not proceeded far, when an order was sent after

him countermanding his march, in consequence of a mutiny among the

Highlanders, who refused to march into England. The English horse, after

expostulating with them, threatened to surround and compel them to march;

but Mackintosh informed them that he would not allow his men to be so

treated, and the Highlanders themselves despising the threat, gave them to

understand that they would resist the attempt.

The determination, on the

part of the Highlanders, not to march into England, staggered the English

gentlemen; but as they saw no hopes of inducing their northern allies to

enter into their views, they consented to waive their resolution in the

meantime, and by mutual consent the army left Jedburgh on the 29th of

October for Hawick, about ten miles to the south-west. While on the march to

Hawick, a fresh mutiny broke out among the Highlanders, who, suspecting that

the march to England was still resolved upon, separated themselves from the

rest of the army, and going up to the top of a rising ground on Hawick moor,

grounded their arms, declaring, at the same time, that although they were

determined not to march into England, they were ready to fight the enemy on

Scottish ground. Should the chiefs of the army decline to lead them against

Carpenter’s forces, they proposed, agreeably to the Earl of Wintoun’s

advice, either to march through the west of Scotland and join the clans

under General Gordon, by crossing the Forth above Stirling, or to co-operate

with the Earl of Mar, by falling upon the Duke of Argyle’s rear, while Mar

himself should assail him in front. But the English officers would listen to

none of these propositions, and again threatened to surround them with the

horse and force them to march. The Highlanders, exasperated at this menace,

cocked their pistols, and told their imprudent colleagues that if they were

to be made a sacrifice, they would prefer being destroyed in their own

country. By the interposition of the Earl of Wintoun a reconciliation was

effected, and the insurgents resumed their march to Hawick, on the

understanding that the Highlanders should not be again required to march

into England.

The insurgents passed the

night at Hawick, during which the courage of the Highlanders was put to the

test, by the appearance of a party of horse, which was observed by their

advanced posts patrolling in front. On the alarm being given, the

Highlanders immediately flew to arms, and forming themselves in very good

order by moonlight, waited with firmness the expected attack; but the affair

turned out a false alarm, purposely got up, it is believed, by the English

commanders, to try how the Highlanders would conduct themselves, should an

enemy appear. Next morning, being Sunday, the 30th of October, the rebels

marched from Hawick to Langholm, about which time General Carpenter entered

Jedburgh. They arrived at Langholm in the evening, and with the view, it is

supposed, of attacking Dumfries, they sent forward to Ecclefechan, during

the night, a detachment of 400 horse, under the Earl of Carnwath, for the

purpose of blocking up Dumfries till the foot should come up. This

detachment arrived at Ecclefechan before day-light, and, after a short halt,

proceeded in the direction of Dumfries; but they had not advanced far, when

they were met by an express from some of their friends at Dumfries,

informing them that great preparations had been made for the defence of the

town. The Earl of Carnwath immediately forwarded the express to Langholm,

and, in the meantime, halted his men on Blacket ridge, a moor in the

neighbourhood of Ecclefechan, till further orders. The express was met by

the main body of the army about two miles west from Langholm, on its march

to Dumfries.

The intelligence thus

conveyed, immediately created another schism in the army. The English, who

had been prevailed upon, from the advantages held out to the Jacobite cause

by the capture of such an important post as Dumfries, to accede to the

proposal for attacking it, now resumed their original intention of marching

into England. The Highlanders, on the other hand, insisted upon marching

instantly upon Dumfries, which they alleged might be easily taken, as there

were no regular forces in it. It was in vain that the advocates of this plan

urged upon the English the advantages to be derived from the possession of a

place so convenient as Dumfries was, for receiving succours from France and

Ireland, and for keeping up a communication with England and their friends

in the west of Scotland. It was to no purpose they were assured, that there

were a great many arms and a good supply of powder in the town, which they

might secure, and that the Duke of Argyle, whom they appeared to dread, was

in no condition to injure them, as he had scarcely 2,000 men under him, and

was in daily expectation of being attacked by the Earl of Mar, whose forces

were then thrice as numerous ;—these and similar arguments were entirely

thrown away upon men who had already determined at all hazards to adhere to

their resolution of carrying the war into England. To induce the Scottish

commanders to concur in their views, they pretended that they had received

letters from their friends in Lancashire inviting them thither, and assuring

them that on their arrival a general insurrection would take place, and that

they would be immediately joined by 20,000 men, and would have money and

provisions in abundance. The advantages of a speedy march into England being

urged with extreme earnestness by the English officers, all their Scottish